Character Formation through Assessment

2 Why Virtues Matter in Higher Education

Perry L. Glanzer

In 1765, the president of Yale College, Thomas Clapp, published one of the first American college textbooks printed in America. The text was meant for the capstone course taught at all existing American colleges at the time: a course in moral philosophy. This capstone course was considered so important that it was always taught by the college’s president. Thus, it is unsurprising that Clapp began his work by noting, “Ethics or moral philosophy, makes a considerable part of an academic education.”[1]

Compare this vision to the one set forth a few decades ago by the literary scholar Stanley Fish. He articulated in stark terms what had become, for some, the de facto position of the twentieth-century research university: “No doubt, the practices of responsible citizenship and moral behavior should be encouraged in our young adults, but it’s not the business of the university to do so, except when the morality in question is the morality that penalizes cheating, plagiarizing and shoddy teaching, and the desired citizenship is defined not by the demands of democracy, but by the demands of the academy.”[2] Does character formation, in fact, matter for higher education? Can and should the intellect be shaped apart from the shaping of the whole person? And if character formation is central to higher education, what is the opportunity for centers for Christian thought to advance this among students in a pluralistic university?

Virtue Development in the Christian Story

The idea that universities could educate without regard for the shaping of student character would have been unintelligible to earlier theorists of higher education. Clapp insisted, “As Man was at first made in the moral Image or Likeness to God [Gen. 1:26-27], so the recovery of that Image is the greatest duty and highest perfection.”[3] For Clapp, as with most thinkers in the Christian tradition, there were two important elements of being made in God’s image.

First, there is a core element not lost in the Fall. After all, God still established one part of the post-Fall Noahanic covenant on its basis (Gen. 9:6). Thus, Christian thinkers described the image as being “deformed and discolored,” but the image itself was not lost.[4] That is why Clapp argued in his text that we should still “view all mankind as the creatures of God originally made in his Image.”[5]

Second, an original moral telos was lost. As image bearers of God, we were intended to demonstrate God’s virtues. Clapp defined virtue by referring to this truth: “Internal or real virtue consists in an inward temper and disposition of mind, which is like to God and conformable to the moral perfections of his nature; such as holiness, justice, goodness and truth.”[6] It was this moral aspect of the image of God that Clapp saw the liberal arts college as helping students recover.

Christians have always understood that Christ accomplished this task for us by being the sinless and virtuous “image of the invisible God” (Col 1:15), dying on the cross for our sins, and thus providing the way, power, and motivation to recover that lost moral image. Gratitude for God’s love and actions toward us through Christ, and the salvation that Christ provides us, is what then empowers us to acquire virtue. One finds this approach in Paul’s epistles, such as Romans, Galatians, Ephesians, and Colossians, where the first half of the books never provide moral commands but instead first lay out what God has done for us through Christ. Then a hinge verse notes, “Therefore,” (Romans 12:1; Gal. 5:1; Eph. 5:1; Col. 2:16) and proceeds into moral admonitions to acquire and demonstrate various Christian virtues, sometimes in particular identity contexts (e.g., church, wife, husband, children, citizen, toward the weak, strong, pagans, enemy, etc.).

The major Christian traditions have different names for this virtue acquisition process, sanctification (Protestant), vocation to beatitude (Catholic), or theosis (Eastern Orthodox), but they share a key pattern. Often, they refer to the same verses that Clapp partially quotes on page eight of his textbook, 2 Peter 1:3–5, where Peter states:

[God’s] divine power has given us everything needed for life and godliness, through the knowledge of him who called us by his own glory and excellence [(aretḗ)]. Thus he has given us, through these things, his precious and very great promises, so that through them you may escape from the corruption that is in the world because of lust and may become participants of the divine nature. For this very reason, you must make every effort to support your faith with excellence [(aretḗ)], and excellence with knowledge, and knowledge with self-control, and self-control with endurance, and endurance with godliness, and godliness with mutual affection, and mutual affection with love. (2 Peter 1: 3-5 NRSVU)

The Greek word for excellence, aretḗ, is also sometimes translated as “virtue” (the original RSV) or “goodness” (NIV) and is the word translated as “virtue” in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Our faith should lead to the imitation and pursuit of God’s excellence.

In light of this theme, it is no surprise that the major ways biblical writers told us to imitate the triune God all have to do with demonstrating certain moral virtues that the triune God exhibits, such as holiness (Lev. 19:2; I Peter 1:15-16), love (John 15:9-12; Eph. 5:1-2), forgiveness (Col. 3:13), humility (Phil. 2:1-7), service to others (John 13:12-15), and acceptance (Romans 15:7). To restore the image of God we are to acquire God’s virtues.

In other words, the whole biblical emphasis upon being like Jesus did not mean acquiring Jesus’ teaching methods or being single. Instead, it involved the particular acquisition of Jesus’ virtues. Or Clap claimed, “Moral Virtue is a conformity to the moral perfections of God; or it is an imitation of God the moral perfections of his nature, so far as they are imitable by his creatures. In the moral perfections of God are the sole foundation and standard of all that virtue, goodness and perfection which can exist in the creature.”[7] Of course, this reality applies to all humans and not simply those who attend college. We all need to develop virtues to fulfill our original purpose and flourish as human beings.

Higher Education and Advanced Christian Virtue Development for Excellence

The early Christian architects of the university understood the purpose of the university as consistent with this overall divine purpose. Hugh of St. Victor (1096–1141) outlined, in a text that laid the foundation for the liberal arts college in a medieval university, “The liberal arts are particularly meant to help restore within us the divine likeness, a likeness which to us is a form but to God is his nature.”[8] What made the university, especially the liberal arts college, unique was that it not only focused on helping students acquire the virtues necessary to restore the image of God in general or in a particular field (e.g., law or medicine), but educational leaders also understood the liberal arts as helping students think through and acquire excellence in advanced identity contexts. They understood that acquiring God’s moral excellence in particular identities was something that required academic study.

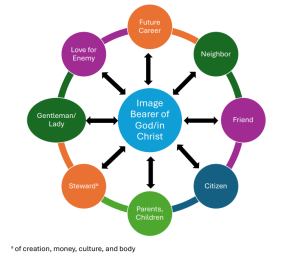

Thus, in a typical moral philosophy textbook used in an American liberal arts college in the 1800s, one would also find chapters discussing how Christian virtue applied to different identity dimensions of one’s life. For example, the president of the College of Rhode Island [Brown University], Francis Wayland, published a popular text on the Elements of Moral Science in 1835 that included sections on one’s duties to God, man, one’s self, property, the rights and duties of parents, the rights and duties of children, duties of citizens, benevolence to the necessitious (those in need), benevolence to the wicked and more.[9] As the last two in particular make clear, the assumption was that applying virtue in specific identity contexts required advanced study. Thus, it was understood that acquiring and demonstrating God’s excellence and virtues often increased in complexity as one matured and engaged in additional forms of identity excellence and leadership within those roles (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. The Christian Vision of Identity Excellence

In this vision, the core identity that guides higher education is that students are image bearers of God who are to acquire God’s virtues. One purpose of higher education is to help them learn how to apply Christian virtues in our various other identities.

The Marginalization of Virtue in Higher Education

By the 20th century, this Christian vision of higher education as forming persons in excellencies corresponding to the image of God no longer animated most colleges and universities. There were a variety of reasons for this failure that have been covered by volumes explaining the secularization of higher education and the marginalization of morality.[10] The most important transformation simply concerned the entities that controlled higher education. After the creation of land-grant universities in 1863, state universities started to gain in numbers and power until, by the early 1950s, the majority of students attended state instead of private universities.

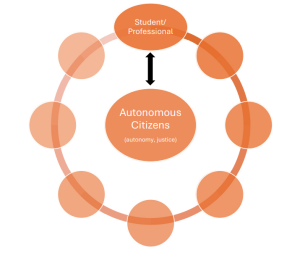

State colleges and secularized elite private universities began to place American citizenship at the center of their approach to education (see Figure 2.2). In addition, with the emergence of the professions and the college major in the late 1800s, the identities of “citizen” and “professional” became the two dominant identity domains in which higher education would engage moral formation. The result of focusing only on moral formation in these two identities meant that wholistic moral formation was marginalized and eventually abandoned. If students were required to take an ethics, it became a professional ethics class. If scholars used an identity today to guide moral education, it involved discussions about “educating citizens.”[11]

Figure 2.2. Citizen at the Center

Thus, as Figure 2.2 illustrates, the purpose of the university shifted from forming bearers of God’s virtues in multiple identities to simply becoming an autonomous citizen who needed to learn the virtues necessary to be a good citizen (justice) and an excellent professional. The other identities are not given significant moral or intellectual attention (that’s why the spheres are blank).

Christians responded to these developments in two ways. First, they joined in supporting the new curricular emphasis since they saw both the defense of Western Civilization and the promotion of professional virtues to achieve the ends of the profession as Christian matters. Second, they addressed the loss of general virtue development by creating parachurch groups that would attempt to retain some aspect of Christian moral formation, such as the YMCA/YWCA, Student Volunteer Movement, Cru, Intervarsity, Newman Centers, and others, that continued the focus on the general development of Christian virtue. Unfortunately, within the college curriculum, attention to virtue development in various identities outside of the citizenship or professional domains disappeared.

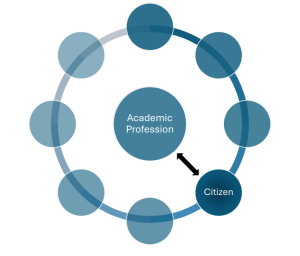

Today, there are others concerned about making citizenship one’s central identity. Stanley Fish’s argument summarized earlier was simply a response to this model. Fish made the argument he did in an attempt to place the academic profession at the center of the university instead of one’s identity as a citizen. He thought that such a placement resulted in the political corruption of the university. For example, according to Fish, the university’s purpose is simply “(1) introduce students to bodies of knowledge and traditions of inquiry they didn’t know much about before; and (2) equip those same students with the analytical skills that will enable them to move confidently within those traditions and to engage in independent research should they choose to do so.”[12] In his view, the university should simply concern itself with one’s identity as a student or learner (see Figure 2.3). Thus, it should only concern itself with academic and professional virtue. Whether the professional virtue helps one acquire virtues in the other spheres, such as being a citizen, is mere happenstance.

Figure 2.3. The University at the Center

To some degree, Fish’s vision has prevailed within the curriculum. Students today are only likely to take a required professional ethics course within their major (e.g., business ethics, medical ethics, etc.). Yet, when it comes to the structure of the university as a whole, especially in the co-curricular, the emphasis on developing autonomous, self-authored citizens still dominates the vision of student development. That is, students are supposed to become self-authors who can construct their own good lives and views of excellence instead of simply inheriting them from a moral tradition.

Since the 1960s, universities have added a couple of additional elements. They emphasize that the groups to which citizens are supposed to show justice are certain previously marginalized identity groups associated with particular races, genders, or sexual identities (see Figure 2.4). The “virtues” of diversity, equity, and inclusion are then understood as the new virtues by which one achieves justice. Virtue education does not disappear, it simply becomes reduced and deformed. As one can see from Figure 2.4, this approach is a far cry from what Clapp envisioned in his first moral philosophy textbook.

Figure 2.4. The Moral Domains of the Post-1960 University

Figure 2.4 illustrates how the purpose of the university shifted from forming bearers of God’s virtues in multiple identities to simply becoming an autonomous citizen who needed to learn the virtues necessary to be a self-authored citizen (justice and autonomy) and an excellent professional. Scholars give attention to our racial, gender, and sexual identities but faculty rarely engage in conversations about what it means to be an excellent man or woman (a nineteenth century concern). Instead, it views those identities merely as important extensions of citizenship. Since persons with these identity markers have been shown injustice in the past, the university gives them special attention to the nation can exercise social justice.

Beyond Intellectual Formation to Identity Excellence

Christian universities and centers for Christian thought at secular universities have sought to address the reductionistic nature of the university, as well as its secularization, by helping expose students to the riches of the Christian intellectual tradition. They seek to help students understand the Christian narrative and learn to think Christianly. Of course, as Clapp demonstrates, Christians believe that a university (or at least Christian institutions associated with the university, such as centers for Christian thought) should focus on the development of the whole person—a central part of which is the recovery of the image of God and God’s virtues.

The contemporary danger facing these Christian educational leaders, however, is that they think they will have accomplished their task simply by helping students “think Christianly,” making the development of a Christian worldview their focus. Yet, as demonstrated above, the Christian tradition has historically believed that the end of Christian education is not simply acquiring a Christian worldview, but it also entails acquiring various forms of excellence (aretḗ) appropriate to those who bear God’s image.

That pursuit requires knowledge of God’s story and what God has done for us to help motivate us. In addition, it requires learning the appropriate end and the knowledge necessary to reach that end, but it also requires specific virtues to achieve excellence in each identity field. To educate students simply to be Christian thinkers is also to reduce the Christian vision of the human person and of excellence to its cognitive dimension. Our students need more to be who God has designed them to be. They need the full range of Christian virtues to fulfill our original purpose—to image God. We image God through the pursuit of excellence in every identity dimension, and such excellence requires virtue.[13]

The Opportunity for centers for Christian Thought

Christian leaders in the contemporary university, especially those leading centers for Christian thought, have a unique opportunity. Scholars have noted that virtue development requires thick moral communities that provide guiding meta-identity for humanity.[14] For example, eight of the twelve exemplar institutions profiled by Anne Colby et al. in their national study of moral education had a shared identity at the core of their educational community and mission.[15] Colleges and universities that succeed in virtue development also nurture a consistent meta-narrative and meta-identity, define and delineate a set of virtues, engage participants in practices that develop these virtues, and do so under the guidance of moral mentors and models for life as a whole. In addition, these institutions can have more focused conversations about the combining and ordering of identities related to virtue and excellence (e.g., what virtues are necessary to be an excellent Christian doctor, historian, psychologist, etc.).[16] Centers for Christian thought at pluralistic universities already exhibit these qualities. In fact, if we look at the stated missions, aims, and current research, it suggests that such centers are already doing this work. These centers are seeking to help students recover what it means to be a fully developed image bearer of God by demonstrating God’s virtues. They are seeking to help students integrate those virtues as they learn what it means to be an excellent Christian scholar, friend, neighbor, family member, steward, and more. The rest of this toolkit seeks to provide ways for centers for Christian thought to enhance this important work they are already doing through the assessment of virtues.

- Thomas Clap, An Essay on the Nature and Foundation of Moral Virtue and Obligation: Being a Short Introduction to the Study of Ethics: For the Use of the Students of Yale-College (New Haven, CT: B. Mecom, 1765), 1. ↵

- Stanley Fish, Save the World on Your Own Time (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 67. ↵

- Clap, An Essay on the Nature and Foundation of Moral Virtue, 54. ↵

- Gerald Boersma, Augustine’s Early Theology of Image: A Study in the Development of pro-Nicene Theology (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016), 261. ↵

- Clap, An Essay on the Nature and Foundation of Moral Virtue and Obligation, 57. ↵

- Clap, An Essay on the Nature and Foundation of Moral Virtue and Obligation 7 (italics in original). ↵

- Clap, An Essay on the Nature and Foundation of Moral Virtue and Obligation, 3 (italics in original). ↵

- Hugh of St. Victor, The Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts, trans. Jerome Taylor (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 52. ↵

- Francis Wayland, Elements of Moral Science (Gould, Kendall & Lincoln, 1835). ↵

- Perry L. Glanzer, The Dismantling of Moral Education: How Higher Education Reduced the Human Identity. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield), 2022. ↵

- See for example Anne Colby, Thomas Ehrlich, Elizabeth Beaumont, and Jason Stephens, Educating Citizens: Preparing America’s Undergraduates for Lives of Moral Responsibility (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003) Derek Bok, Our Underachieving Colleges: A Candid Look at How Much Students Learn and Why They Should Be Learning More (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008). ↵

- Fish, Save the World on Your Own Time, 18. ↵

- Jason Baehr, “The Varieties of Character and Some Implications for Character Education,” Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46 (2017): 1153-1161. ↵

- Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue, 3rd ed. (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007); Perry L. Glanzer & Todd C. Ream. Christianity and [pb_glossary id="889"]Moral Identity[/pb_glossary] in Higher Education: Becoming Fully Human (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009). ↵

- Anne Colby, Thomas Ehrlich, Elizabeth Beaumont, and Jason Stephens, Educating Citizens. The types of identity connected with these institutions included [pb_glossary id="902"]religion[/pb_glossary] (Alverno College, the College of St. Catherine, Messiah University, Tusculum College, and University of Notre Dame); ethnicity and/or race (Spelman College, Turtle Mountain Community College), gender (College of St. Catherine and Spelman College), and professional identity (United States Air Force Academy). ↵

- Perry L. Glanzer, Identity Excellence: A Theory of Moral Expertise for Higher Education (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2022). ↵

That which is relevant to what is ethically right, wrong, good, or bad.

Efforts to cultivate a person’s or group’s morally good habits (Berkowitz, 2012). Character formation happens most commonly in the context of moral communities such as families, schools, religious/spiritual communities, community-based organizations, faith-based organizations, and virtue-aspiring organizations ("11 Principles for Cultivating a Culture of Character").

The collective group of Christian study centers and institutes for Catholic thought (Cockle et al., 2024).

The totality of a person or group's morally relevant habits of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating (Baehr, 2017). People's character can vary considerably in how good or bad it is and how coherent and contextually adaptive it is across time and situations (Lerner, 2019).

A set of beliefs, values, affiliations, and roles a person uses to define their sense of self (“who I am”) and guide their decisions and behaviors (“how I live”). In short, an identity refers how a person self-defines who I am and how I live. An identity can also be communal, namely how a group of people collectively defines who we are and how we live (Oyserman, Elmore, Smith, 2012). See also meta-identity.

“Systematic [internal] changes of [a person or group’s] behavior, and of the systems and processes underlying those changes and that behavior” (Overton, 2010).

A group of people with a shared sense of what is ethically right, wrong, good, or bad and a shared set of norms for guiding ethically relevant decisions and behaviors. Christian colleges/universities and centers for Christian thought are two types of moral communities in higher education.

A person or group’s most prominent identity, under which all other identities are ordered. For example, a Christian meta-identity refers to when a person or group’s most prominent identity is Christian, such that they define themselves foremost as a Christian and their ultimate motivation is to behave and make decisions congruent with their set of Christian beliefs, values, affiliations, and roles. A meta-identity can be thought of as a “master identity.”

The overarching term used to describe the process of collecting and analyzing data to make an informed decision.

Feedback/Errata