Character Formation through Assessment

3 How to Cultivate Virtues: Theory of Change and Program Strategies

Andrew Z. Hansen; Karen K. Melton; Theodore F. Cockle; and Edward B. Davis

Growth in character can seem a mysterious and complex process over which we exercise little direct control. Humans are exceedingly complex creatures, and we only see and understand a few of the many factors that shape our character. And yet, despite this complex reality, we can take steps––for ourselves and others––to help direct character growth processes. How is this possible?

Imagine character formation through the analogy of gardening . Plant growth is a highly complex process––we’re only beginning to understand the complex ecological systems affecting plant growth––and gardeners know that they only exercise limited influence in this process (ask anyone who’s ever lost an entire crop of tomatoes to blight!) However, gardeners still use their limited knowledge and influence to facilitate better plant growth. Analogously, while we may have limited knowledge and influence over the many factors that shape our own and others’ character, we can indeed do some things to help character develop in certain ways rather than others.

Choosing activities for character growth can be aided by a “theory of change” with respect to character formation. A theory of change is a set of beliefs informing how we think change happens. In the case of character formation, it’s how we think virtues actually grow in people. Everyone working in Christian ministry holds some idea about how people change.[1] A major reason to be explicit about our theory (or theories) of change is that doing so can help us be more intentional in choosing which activities to engage in and when. A good theory of change should make program decisions clearer: Given (1) how you think change happens, (2) your goals for change, and (3) your limited time and resources, which activities will you prioritize when designing your programs?

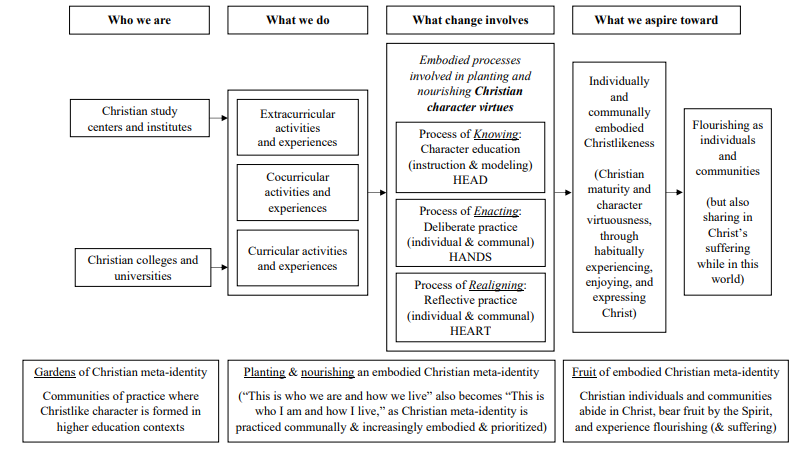

In the DC3 research project, our team developed a three-fold theory of change (illustrated in Figure 3.1) to describe character formation in college students connected with moral communities, including centers for Christian thought.[2] Within these “gardens” of Christian identity, students engage in activities that nourish an embodied Christian meta-identity. These activities contribute to three overlapping processes through which student character––the “fruit” of an embodied Christian identity––is formed. We’re describing these three processes with the keywords Know, Enact, and Realign:

- Know (Head): Students form “transcendent narrative identity” within Christian moral communities.

- Enact (Hands): Students practice virtues.

- Realign (Heart): Students consider their past and future behavior, evaluating if it aligns (or will align) with their Christian identity.

Figure 3.1. Developing Christian Character in Higher Education: Theory of Change

Before offering a fuller description of each these process, three brief notes. First, it is important to note that this theory assumes a dynamic interaction between a student and his or her various communities. Character formation is not an individualistic, isolated process but a communal one. Second, it’s important to note that these three processes are not successive, linear stages. I don’t first form a moral identity, then begin to enact virtues consistent with that identity, and finally reflect on whether or not I am acting in alignment with that identity. Rather, these processes often happen simultaneously, acting and reacting upon one another. For this reason, we theorize that college students must regularly engage in all three of these processes for effective character formation. Third, it’s important to note that students engage in these processes in many more contexts and communities than just your center. While it may make sense for some centers to facilitate all of these processes in a single program or across programs, others may choose to focus on just one or two of these processes in their programs. That decision depends significantly upon the context you’re working within and the resources available to your students and your center.

1. Know (Head)

Character is always informed by a “transcendent narrative identity.”[3] That is, we make sense of ourselves and our actions as part of some larger story (or stories) that connect us beyond ourselves. As Christian Smith says, humans are “made by our stories.”[4] Our stories about the world give a sense of purpose and meaning to our lives and provide the moral direction (the “oughts”) that guides our behavior. We’re most deeply motivated to act in certain ways when we can see how those actions will move us toward some good end within a particular larger story (or “metanarrative”).

We like to think of ourselves as the authors of our own stories, and to some extent we are. We have real agency in the world, and a story only motivates us when we internalize it and begin acting with agency within that story, so to speak. But the reality is that these stories mostly come from beyond ourselves. We form our narrative identities through interactions with the broader communities, cultures, and traditions that we’re embedded within. As part of multiple communities, our students regularly encounter multiple metanarratives that press moral imperatives upon them. Students arrive on college campuses already shaped by the different communities they’ve belonged to for many years: family, friends, churches, and schools. While at the university, students are exposed to many new experiences and communities that may challenge, undermine, reinforce, or revise the identities they initially brought to campus, leaving college with a different (and hopefully better) understanding of their place within the world.

If our aim is to help students grow in Christian character ––loving God and loving neighbor well––then helping them know themselves within a Christian metanarrative is an essential part of this process. Our centers can offer students a Christian moral community that is explicitly and implicitly helping students grasp and internalize this Christian story, finding their place and purpose within it. As discussed in Chapter 2, as students begin to find their identity within this story, certain kinds of actions––virtues––begin to make sense for them, in line with the goal or telos of humanity within that story.

In a substantial way, students come to know this through explicit teaching about the Christian tradition. Helping students understand and appreciate Christian theology found in Scripture and tradition is one of the main contributions that our centers offer students. Because excellent training in the Christian theological tradition is increasingly rare on our campuses and even in our students’ churches, centers for Christian thought play a valuable role in introducing students to and deepening their appreciation for the Christian story, giving them a sense for how their own lives make sense within this story. And when we look at the programming offered by centers for Christian thought, it is this level of explicit teaching of Christian and biblical theology that most stands out. Almost all centers offer direct instruction in the Christian narrative through lectures, Bible studies, curricular fellows programs, extra-curricular or for-credit courses, reading groups, and so on.

But this kind of direct instruction is just one (albeit essential) facet of the Know process. We come to know these metanarratives that frame our moral identities in more embodied ways as well. When we enact metanarratives through ritual or bodily practices, they connect with us and move us in ways that direct instruction often doesn’t. Students’ participation in Christian prayer, music, and other liturgical practices––at our centers but also in their churches and other Christian ministries––is a major way that students come to know the Christian story in a deeply embodied and affective way. So, too, can engagement with works of art or imagination that illustrate and illuminate themes from these metanarratives.[5] In the course of our research study, we learned that one center, for instance, offers daily Scripture reading as a way for students to immerse themselves in the Christian story by reading aloud and hearing read large portions of Scripture. Another center described how an experiential learning trip to a local urban farm helped students better discern through tangible experience their own place in the creational order, giving them a vision for why self-control is needed in our engagement with the natural world. In these and other ways, coming to form one’s transcendent narrative identity is caught, through embodied experience, as much as it is taught in explicit instruction.

2. Enact (Hands)

Aristotle understood that character development does not come simply by knowing the way one should act, but by practicing it.[6] Some contemporary scholars of character development summarize it this way:

Students cannot learn how to improve their character simply by reading a book or applying an abstract formula they learn in class. Rather, they must learn virtues of character, in part, by doing virtuous actions. For a good disposition to become a stable and enduring virtue, it must become a kind of habit––a deep reliable, and entrenched disposition of thought, feeling, or action.[7]

Accordingly, the second process in our theory of change is Enact, meaning that students have opportunities to practice certain virtues.

Again, it is important to remember that most opportunities for college students to enact virtues do not occur in the context of our centers. Daily life in college––interactions with roommates, classmates, and professors, time spent exercising or studying, and choices about how to spend one’s free time––is filled with opportunities for students to practice different virtues. How students choose to act in each of these instances shapes their character in small ways. And, just as with moral identity, students arrive on campus already habituated in certain ways through years of enacting virtues and vices.

And yet, as students spend time with us in our programs and in our communities, we also have many opportunities to directly build contexts and foster cultures that support students in enacting Christian virtues. Sometimes, this occurs through more programmatic virtue-development exercises. One center in our study structured time during a retreat for students to write notes of gratitude to one another. In other instances, these opportunities can be woven more organically into the everyday life of the center. Centers can implement structures that encourage students to act in virtuous ways, even in ways that they might not tend to act when left to themselves or in other contexts. During final exams, we’ve sometimes constructed a “wall of gratitude” for students at Anselm House to express publicly what they’re grateful for, even amid the stress of finals. To return to the earlier example of daily Scripture reading, center staff described how the daily practice of quietly attending to long passages of Scripture each day offers students daily opportunities to practice self-control (among other virtues). Perhaps the most powerful, but almost invisible, virtue-shaping effect of our centers occurs when we’re able to foster a holistic culture that promotes virtuous living, where a significant percentage of the community are enacting virtues in their day-to-day interactions. That culture then shapes students not only through our formal programs, but through all of the small, informal interactions among students, staff, and others that are facilitated in and through our centers. (For this reason, we’ve included in this toolkit an organizational assessment, to discern the broad level of virtue present in your organizational culture.)

As a final note, it’s important to remember that virtue requires the right action with the right motives, and so not every action that appears to be virtuous is, in fact, virtuous.[8] However, as C. S. Lewis observed, sometimes right motivation only develops in the process of learning a habit or skill.[9] Thus, even things done with initially less-than-fully-virtuous motivations can, through repetition and seeing their connections with Christian identity (the Know process) become a true enactment of a virtue. Here is where it is helpful to remember that, on this theory of change, growth and maturation in character usually happens when students engage in all three of these processes simultaneously.

3. Realign (Heart)

The third process in student character formation involves reflection on the alignment between identity (Know) and action (Enact). Realignment involves students reflecting on where in life, specifically and concretely, they have or have not been enacting virtues that align with their Christian identity, and developing resolutions and plans for how they can practice these virtues in the future.[10] In theological terms, realignment means evaluating the extent to which they are being conformed into the image of Jesus.[11]

This realignment process is a major area of opportunity for centers to support character formation in students because, in the realignment process, students are encouraged to think carefully about all of the life contexts in which they are or aren’t living virtuously. Since time is one of the major limitations in our centers’ work with students–– most students only spend a fraction of their time at our centers––it is encouraging to think that activities focused on realignment may vastly expand our impact by leveraging so much of students’ experiences outside of our centers towards the ends of character formation.

Realignment can occur through many kinds of activities. Basic Christian liturgical and spiritual practices often offer excellent opportunities for realignment, usually with elements that also help students engage in the Know and Enact processes at the same time. Confession of sin that occurs within liturgical services or personal prayer is an obvious place where students reflect on whether or not they’re living in alignment with their Christian identity. Similarly, the Ignatian Examen prompts practitioners to reflect on the experiences of their day, identifying where they were drawn toward or away from God through those experiences. Centers can also design intentional conversations that prompt realignment––for example, a group conversation about how students have or have not been practicing patience or self-control in preparing for exams. As part of our research, one center described the structured opportunities for reflection and feedback within its internship program that help interns reflect on and further develop self-control, among other virtues. As part of this toolkit, we’re including several reflection worksheets that can be used to guide students through a process of evaluating how they’re practicing a particular virtue and how they might see continued growth in that area. We’re also including a guide to informal personal conversations with students that can be used to help students reflect on their character as a means toward encouraging further growth.

This three-fold theory of change for student character formation––Know, Enact, Realign––offers a powerful way for thinking carefully about which activities our centers provide to help students engage in all three processes needed to cultivate Christian character. It allows us to select strategies and activities as part of our center programs that target the areas of greatest need for our students, given how students are or are not engaging in these three processes in contexts beyond our centers.[12] The remainder of this toolkit will help you assess the extent to which character growth is happening at your centers––fostered through your programs and present in your organizational culture as a whole––and how character assessment itself can serve as an important aid in cultivating character.

- In explaining why theories of change matter, theologian Simeon Zahl writes, “[E]very ministry makes basic theological assumptions about human nature and about how God works in people’s lives. In more theological terms, you could say that every form of ministry has an implicit theological anthropology and an implicit theology of grace.” Zahl, “How Do People Actually Change? The Cure of Souls and Theory of Change in Christian Ministry,” Mockingbird (https://mbird.com/the-magazine/the-cure-of-souls/) ↵

- While part of our project involves the empirical testing of this theory, the theory itself is based on a considerable body of empirical and theoretical research on [pb_glossary id="887"]moral development[/pb_glossary]. ↵

- Schnitker, King, Houltberg, 2019. ↵

- Christian Smith, Moral, Believing, Animals: Human Personhood and Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 64. ↵

- For an excellent discussion of these themes in Christian practice, see James K. A. Smith’s Cultural Liturgies trilogy, especially Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation and Imagining the Kingdom: How Worship Works. ↵

- See Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Book 2, Ch. 1. Jesus also emphasized the importance of right action (“Blessed rather are those who hear the word of God and keep it!” Luke 11:28) and the Epistle of James urges us to “be doers of the word, and not hearers only, deceiving yourselves” (James 1:22). ↵

- Lamb et al., “Seven Strategies for Cultivating Virtue in the University,” in Cultivating Virtue in the University (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022). ↵

- E.g., Matthew 6:1-18. ↵

- C. S. Lewis, “The Weight of Glory,” in The Weight of Glory (HarperOne, 2001), 26-28. ↵

- As we’re using it here, “realignment” brings together elements from two virtue cultivation strategies listed by Lamb et. al.: “reflection on personal experience” and “friendships of mutual accountability.” Lamb et. al., “Seven Strategies,” 122-124, 135-138. ↵

- Rom. 8:29. ↵

- An excellent resource (from we’ve already drawn in this chapter) on strategies for cultivating virtue among college students is Michael Lamb et al. “Seven Strategies for Cultivating Virtue in the University.” ↵

The totality of a person or group's morally relevant habits of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating (Baehr, 2017). People's character can vary considerably in how good or bad it is and how coherent and contextually adaptive it is across time and situations (Lerner, 2019).

Efforts to cultivate a person’s or group’s morally good habits (Berkowitz, 2012). Character formation happens most commonly in the context of moral communities such as families, schools, religious/spiritual communities, community-based organizations, faith-based organizations, and virtue-aspiring organizations ("11 Principles for Cultivating a Culture of Character").

an activity or set of activities that are grouped together for the purpose of achieving a specific outcome

A group of people with a shared sense of what is ethically right, wrong, good, or bad and a shared set of norms for guiding ethically relevant decisions and behaviors. Christian colleges/universities and centers for Christian thought are two types of moral communities in higher education.

The collective group of Christian study centers and institutes for Catholic thought (Cockle et al., 2024).

A set of beliefs, values, affiliations, and roles a person uses to define their sense of self (“who I am”) and guide their decisions and behaviors (“how I live”). In short, an identity refers how a person self-defines who I am and how I live. An identity can also be communal, namely how a group of people collectively defines who we are and how we live (Oyserman, Elmore, Smith, 2012). See also meta-identity.

A person or group’s most prominent identity, under which all other identities are ordered. For example, a Christian meta-identity refers to when a person or group’s most prominent identity is Christian, such that they define themselves foremost as a Christian and their ultimate motivation is to behave and make decisions congruent with their set of Christian beliefs, values, affiliations, and roles. A meta-identity can be thought of as a “master identity.”

A person’s or group’s internalized, evolving story about themselves and how they fit into a story bigger than themselves (Schnitker, King, and Houltberg, 2019).

The set of beliefs, values, affiliations, and roles a person or group uses to define their ethically relevant sense of self and guide their ethically relevant decisions and behaviors.

That which is relevant to what is ethically right, wrong, good, or bad.

“A person’s [or group’s] internalized and evolving life story, integrating the reconstructed past and imagined future to provide life with some degree of unity and purpose" (McAdams and McLean, 2013).

Systematic internal changes in the structure, function, and patterns that characterize a person’s or group’s morally relevant habits of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating (VandenBos, 2015).

“[A disposition] to give a [particular] response in a particular context" (Wood, Labrecque, Lin, Rünger, 2014).

The overarching term used to describe the process of collecting and analyzing data to make an informed decision.

Feedback/Errata