Character Formation through Assessment

4 Approaches to Character Assessment

Karen K. Melton

Character assessments can offer numerous benefits for organizations and students. Assessing virtues can help organizations evaluate effectiveness, tailor interventions, provide individualized feedback, and ensure continuous program improvement specific to the cultivation of character. Additionally, assessment data can enhance accountability, motivate participants, and contribute to the broader field of character development research.

The specific benefits derived from an assessment depend on the chosen assessment approach. In this toolkit, we define “assessment approach” as the set of research methods or techniques used to evaluate virtues[1]. Assessments can be categorized as either informal or formal:

- Formal Assessments: aim to record scores/data for comparative purposes. For example, exams in a classroom setting allow teachers to compare student scores to a standard.

- Informal Assessments: focus on activities for personal information/data collection. For instance, worksheets help students gauge their current abilities or understanding of a topic.

Assessment methods vary in complexity and can employ both quantitative and qualitative data collection techniques. Experts often note that effective evaluation combines the science and the art of assessment. For those interested in mastering these aspects, Kathryn Newcomer and colleagues’ “Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation” offers over 800 pages of comprehensive information on assessment methods[2] .

This toolkit simplifies the balance between the science and art of assessments by providing practical guides using both informal and formal approaches:

- Part 2: Informal assessment guides and tools for personal reflection.

- Part 3: Formal assessment guides and tools for program evaluation and organization monitoring.

Each guide covers core assessment steps: data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation. These steps are tailored to distinct assessment approaches, offering insights into virtues at various levels—students, programs, and organizations.

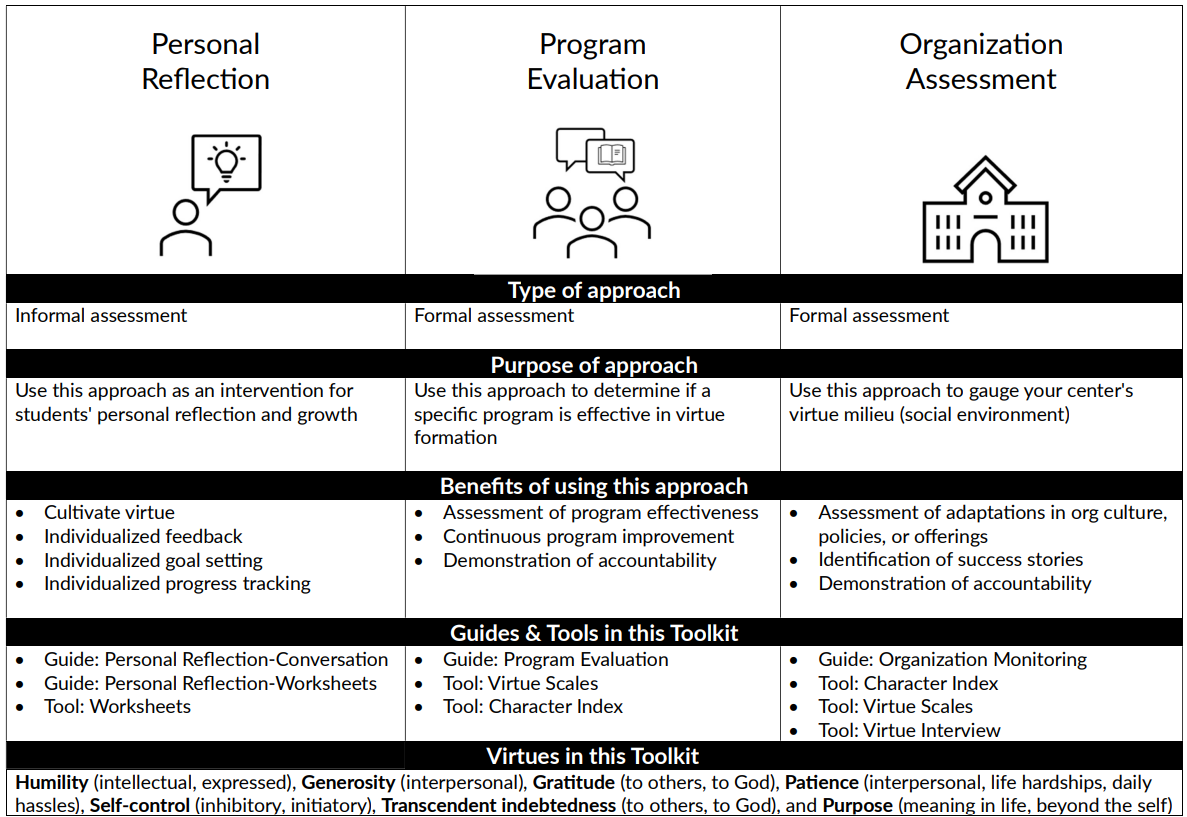

This chapter provides insight into the three assessment approaches to help practitioners choose the appropriate guide. Table 4.1 provides an overview of these approaches, enabling practitioners to select the most suitable methods for their specific needs.

Table 4.1. Three Approaches for Assessment[3]

Personal Reflection

The step-by-step guides for Personal Reflection use informal assessment methods that will be useful to centers that do not want to collect data on their students but rather are interested in using the assessment tools for students’ growth. Centers may choose to use this approach in a specific program or with all students associated with their center. Two step-by-step guides are provided. One guide focuses on personal reflection via a one-on-one conversation, like over a cup of coffee. The other focuses on personal reflection using worksheets specific to a virtue (e.g., patience, humility, etc.) that might be used in one session of a program or class. The guides provide the steps needed for facilitating the virtue assessment tools as an intervention for students to gain personal reflection and goal-setting related to virtues. If this approach is used over time with the same students, it can also provide these students a means for tracking their growth over time.

We included this approach in the toolkit because, as part of our research study, students identified how meaningful the questions were to their own growth. Students were asked to complete a one-hour questionnaire four times over the course of two years. Initially, our research team expected many complaints from students, but we were surprised by the overwhelmingly positive responses we received. Students from the centers states that they enjoyed taking the surveys and viewed them as an opportunity for deep self-reflection, individual feedback, and goal setting.

“I’ve enjoyed doing these surveys and am excited to see what you find!”

“Thank you for allowing me to reflect on my life with this survey!”

“I appreciated taking this survey, and I really enjoyed reflecting on my goals.”

“I really enjoy taking this survey because it helps me see how I’ve changed over the past year since coming to college.”

“I love taking this quiz! It makes me feel good about myself afterward and helps me process my thoughts and goals!”

Scholars have noted that taking a questionnaire can be a catalyst for change in a person’s life. The deep reflection that occurs for a person when answering a questionnaire can provide an opportunity for cognitive dissonance. This can occur when individuals experience tension between inconsistency in the person that they want to be and the person that they are.

For example, in a survey, I might be asked the question, How much do I agree with the statement: ‘I am patient with other people.’ In response, I may want to say “strongly agree;” however, when I am being truthful with myself, I choose the option “disagree” based on my current behaviors. What we have witnessed in this example is a psychological phenomenon referred to as cognitive dissonance[4]. Humans desire internal consistency, thereby causing discomfort when the desired response conflicts with current behavior. In most situations, this discomfort motivates action to alleviate the internal tension. Humans may employ a range of strategies to mitigate this discomfort, including changing their beliefs or attitudes, recalibrating the importance of values, engaging in new behaviors, or feeling less responsible for current behavior.[5]

From our research study, we found that center students shared their sincere appreciation for questions that provide cognitive dissonance, and these questions may have been a catalyst for reflecting on their virtues and growth over time:

“Thank you for the time you took to craft this survey. It is a time to reflect on my life goals and to recommit each time this survey is taken.”

“Thanks for the survey! The questions were very thought-provoking and encouraged me to perform a deep self-reflection.”

“I began doing these surveys for the gift cards, but the experience has been very valuable and therapeutic to think about and genuinely answer questions I may have gone years without asking myself. I really appreciate you guys. (This participant refused payment).”

“My answers have for sure changed over time.”

“Thanks for the opportunity to be encouraged to sit and reorient myself despite the busy college life!”

“This survey asked questions that really made me think and allowed me to think about my life more personally and in a deeper way.”

In addition to the positive impact that questionnaires can have on students’ beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors; it is also important to note that taking questionnaires may also bring up difficult feelings and experiences.

“It’s helpful to reflect on these things; the survey has made me realize that I do feel very lonely despite having a good family and close friends. I don’t understand why.”

“I’m struggling a lot with legalism in faith right now. I deeply appreciate the readings {center} gives me, but often, the more readings I have to think about, the easier it is for me to make new rules I have to follow to be a good Christian. Also, the {center} staff do help me with a lot of problems – I don’t think they’ve necessarily shown me how to ask for help, but I just do it myself because I already know how.”

“My dad has passed away, I wish there was an option for that when talking about father figures.”

Therefore, regardless of which approach you take to virtue assessment, we highly recommend connecting students to mental health and religious support. With this in mind, many of our guides will include a section on connecting students to additional support.

Personal Reflection: Next Steps

Personal Reflection is an informal assessment that provides an opportunity for students’ personal reflection and growth.

In this toolkit, we provide you with two ways of engaging students in personal reflection. One way is through a one-on-one Character Conversation. The other way is through using Virtue Worksheets. If you are interested in this approach, then read through the related guides and tools:

Program Evaluation

The step-by-step guide for Program Evaluation will be useful to centers that have intentionally designed a program to facilitate students’ virtue formation. Therefore, if you are interested in collecting information that helps to address the question—Is {PROGRAM} effective at increasing {VIRTUE}?—then this approach is right for you.

Program evaluations are a systematic method for collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data to demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of a program. If you are new to evaluations, that definition can be a bit overwhelming. So, let’s break this down.

First, let’s talk about the concept of a program. A program is an activity or set of activities that are grouped together for the purpose of achieving a specific outcome. For example, a program may group together three activities: (1) eating a meal together, (2) book reading, and (3) reading discussion–and call this group of activities the Monday Night Dinner Club. The goal of Monday Night Dinner Club may be to (a) increase a sense of belonging and (b) increase knowledge on a particular topic. In your organization, you probably have several programs.

Second, let’s talk about the concept of an evaluation. An evaluation is a systematic method for making a decision. This simply means that we follow a process, and there are specific steps that we can follow to gather the information to make a decision. Specifically, these steps include collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data (data is just another word we use for information).

Why do we want this information? Well, we can use this information for several purposes: First, we may want the information to demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of a program—that is, to be able to tell stakeholders our program has the impact that we think we are having on our students. For example, if we claim that students in the Fellowship program are more patient, how do we know if they are more patient unless we measure their change in patience as a result of their participation in the Fellowship program?

Another reason we may seek information about our program is to make informed decisions about future programming. Organizations can allocate their budgets more wisely when they clearly understand which programs are effective. This means that information about the program can help us decide which programs to fund further, recruit more participants, and modify or discontinue because they are ineffective.

PROGRAM EVALUATION: NEXT STEPS

Program evaluation is a formal assessment that allows centers to collect data to address the question—Is {PROGRAM} effective at increasing {VIRTUE}?

In this toolkit, we provide a simple approach that can be useful to small programs to conduct evaluations for specific virtues. If you are interested in this approach, then read through the related guides and accompanying tool:

While our guide focuses on conducting program evaluations using the specific virtue scales, you may also be interested in using the Character Index to identify an increase in multiple virtues at one time:

Organization Monitoring

The step-by-step guide for organization monitoring will be useful to centers that are interested in identifying the center’s virtue milieu (social environment). Recall that in program evaluation, it is assumed that a program was specifically designed to facilitate virtue development. However, centers may not develop a program with an explicit goal that students grow in virtue (e.g., intellectual humility, generosity, etc.). For example, one center leader said:

Our goal is to cast a vision of the Christian narrative for our students. Our role is not really on the side of virtue formation. So, a checklist of virtues and how to build a program around a virtue seems overwhelming. I feel less overwhelmed when virtues are just a natural language of what we do in living in a Christian community.

Another leader identified instilling Christian thinking as a first-order outcome of the programs and the virtues as a second-order outcome of participating in the center programs over time. In other words, virtues are the fruit produced from living a Christian life. Center programs may tend to focus on helping students live the Christian life (not on developing virtues). Yet, virtues may be a by-product of being actively involved in the center environment. This thinking was also embedded in our research study that hypothesized that meta-moral communities like centers provide an environment that, over time, facilitates students’ growth in virtues.

Therefore, for many of our centers, a program evaluation would likely be an inappropriate method for assessing the virtue scene of centers. Therefore, we have included organization monitoring as an approach in this toolkit to provide centers with a systematic method for collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data to identify the character profile of your organization. The information gained from this organization monitoring may be used to inform decisions about future programming and organization policies that influence the culture. Information gained from organization monitoring can also be shared with stakeholders to identify the merit or worth of students’ participation.

Organization Monitoring: Next Steps

Organization Monitoring is a formal assessment that allows centers to collect data to identify their character profile, i.e., the virtue milieu of the organization.

This toolkit provides a simple approach using quantitative and qualitative methods to develop a character profile. If you are interested in this approach, then read through the related guides and tools:

While our guide focuses on conducting organization monitoring using the character index and interview, you may also be interested in using the specific virtue scales to improve data quality and understand more nuances of virtue formation:

Conclusion

This chapter provides three virtue assessment approaches—personal reflection, program evaluation, and organization monitoring. Determining which approach is best will always depend on the purpose of the assessment—i.e., why does your organization want to conduct a virtue assessment? In this toolkit, we attempt to simplify the balance between the science and the art of assessments by providing practical guides that use informal and formal approaches to assessment. Therefore, in Part 2 of this toolkit, you will find the tools and guides for conducting informal assessments for personal reflection. In Part 3 of this toolkit, you will find the tools and guides for conducting formal assessments for program evaluation and organization monitoring.

- A note on the terminology of [pb_glossary id="216"]assessment[/pb_glossary] and [pb_glossary id="404"]evaluation[/pb_glossary]. Assessment is a synonym for evaluation. We will use the term assessment when discussing the three overarching approaches (or guides) provided in this toolkit. We will use the term evaluation when discussing the specific approach of program evaluation. ↵

- Newcomer, K. E., Hatry, H. P., & Wholey, J. S. (Eds.). (2015). Handbook of practical program evaluation (pp. 1-864). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass & Pfeiffer Imprints, Wiley. ↵

- The names given to approaches in this toolkit are meant to support the learning of the target audience, although other formal or informal names may be used in other resources to describe similar approaches. ↵

- Festinger, L. (1962). Cognitive dissonance. Scientific American, 207, 93–106.10.1038/scientificamerican1062-93 ↵

- Sources: (1) Gehlbach, H., Robinson, C. D., Finefter-Rosenbluh, I., Benshoof, C., & Schneider, J. (2018). Questionnaires as interventions: can taking a survey increase teachers’ openness to student feedback surveys?. Educational Psychology, 38(3), 350-367. (2) Brehm, J. W. (2007). A brief history of dissonance theory. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1, 381–391. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00035.x (3) Gawronski, B. (2012). Back to the future of dissonance theory: Cognitive consistency as a core motive. Social Cognition, 30, 652–668. doi:10.1521/soco.2012.30.6.652 (4) Martinie, M. A., Milland, L., & Olive, T. (2013). Some theoretical considerations on attitude, arousal and affect during cognitive dissonance. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7, 680–688. doi:10.1111/spc3.12051 ↵

The overarching term used to describe the process of collecting and analyzing data to make an informed decision.

an activity or set of activities that are grouped together for the purpose of achieving a specific outcome

The totality of a person or group's morally relevant habits of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating (Baehr, 2017). People's character can vary considerably in how good or bad it is and how coherent and contextually adaptive it is across time and situations (Lerner, 2019).

Systematic internal changes in the structure, function, and patterns that characterize a person’s or group’s morally relevant habits of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating (VandenBos, 2015).

The set of research methods or techniques used to evaluate virtues.

A systematic method for making a decision.

a formal type of assessment used to collect and analyze participant data within a program to make an informed decision on program effectiveness

an informal type of assessment used to collect and analyze personal information to make an informed decision for personal growth

a formal type of assessment used to collect and analyze participant data across the organization to monitor and make informed decisions on organizational culture

“Systematic [internal] changes of [a person or group’s] behavior, and of the systems and processes underlying those changes and that behavior” (Overton, 2010).

A group of people with a shared sense of what is ethically right, wrong, good, or bad and a shared set of norms for guiding ethically relevant decisions and behaviors. Christian colleges/universities and centers for Christian thought are two types of moral communities in higher education.

Feedback/Errata