11 Chapter 11: Ability Identity

Grounding and Groundwork

Choose some ritual(s) that will bring your mind/body into focus as you take in the following chapter.

When you are ready to bring your attention to the material in this chapter:

- Try and remember the first experiences you had and messages you received about ability. Consider multiple dimensions of this term: physical, intellectual, and emotional.

- What did you witness and or what were you told about disabled individuals, individuals with mental health diagnoses and/or neurodivergent individuals in your family settings, educational settings, faith settings, political and/or any other shaping communities of which you were a part?

Defining Concepts

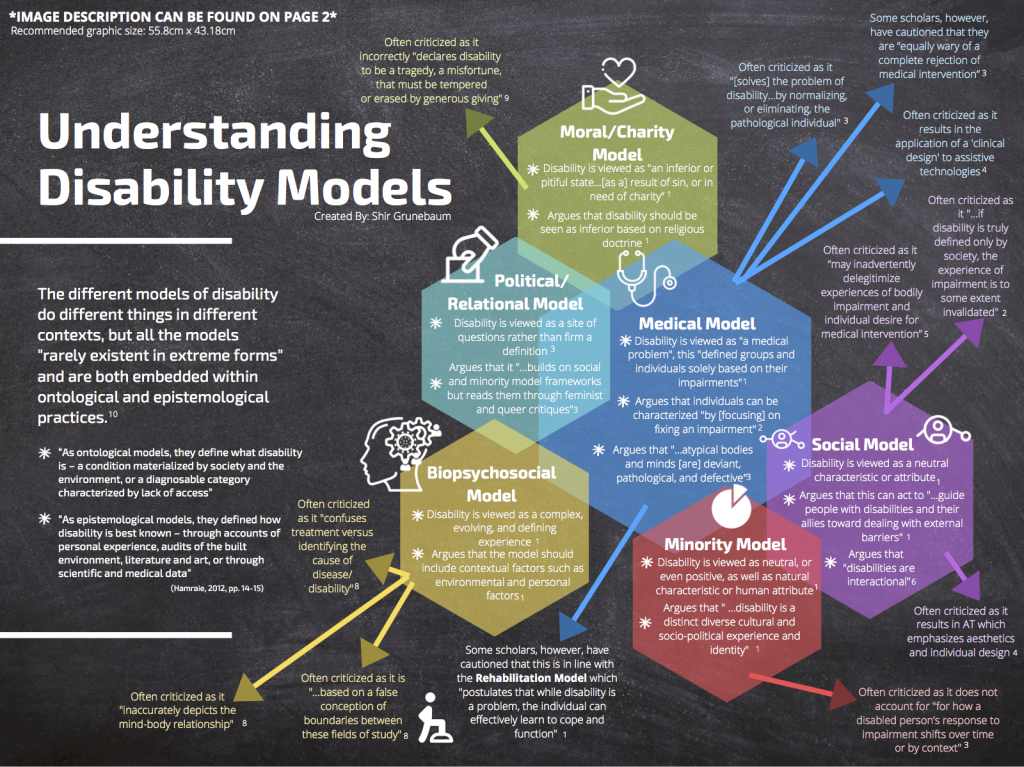

- Disability can be broadly defined as the interaction of physical, psychological, intellectual, and socioemotional differences or impairments with the social environment (World Health Organization, 2001). The members of some groups of people with disabilities—effectively subcultures within the larger culture of disability—have ways of referring to themselves that they would prefer others to adopt. The overall principle for using disability language is to maintain the integrity (worth and dignity) of all individuals as human beings (APA, 2020b)

- Mental Disorder: A mental disorder is a major disturbance in an individual’s thinking, feelings, or behavior that reflects a problem in mental function. Mental disorders cause distress or disability in social, work, or family activities (APA, 2022).

- Ableism is stereotyping, prejudicial attitudes, discriminatory behavior, and social oppression toward people with disabilities to inhibit the rights and well-being of people with disabilities, which is currently the largest minority group in the United States (APA, 2021b; Bogart & Dunn, 2019). Understanding the concept of ableism, and how it manifests in language choices, is critical for researchers who focus on marginalized groups such as the autistic community (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2021).

- In person-first language, the person is emphasized, not the individual’s disabling or chronic condition (e.g., use “a person with paraplegia” and “a youth with epilepsy” rather than “a paraplegic” or “an epileptic”). This principle applies to groups of people as well (e.g., use “people with substance use disorders” or “people with intellectual disabilities”

- In identity-first language, the disability becomes the focus, which allows the individual to claim the disability and choose their identity rather than permitting others (e.g., authors, educators, researchers) to name it or to select terms with negative implications (Brown, 2011/n.d.; Brueggemann, 2013; Dunn & Andrews, 2015). Identity-first language is often used as an expression of cultural pride and a reclamation of a disability that once conferred a negative identity. This type of language allows for constructions such as “blind person,” “autistic person,” and “amputee,” whereas in person-first language, the constructions would be “person who is blind,” “person with autism,” and “person with an amputation,” respectively

- Neurodiversity is a term that evolved from the advocacy movement on behalf of individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and

has been embraced by other groups of individuals with neurologically based disabilities (e.g., learning disabilities [LDs]).

Neurodiversity suggests that these disabilities are a natural variation in brain differences and that the workplace should

adapt to them (Sumner & Brown, 2015). - For more information on person-first and identity-first language, please refer to the APA bias-free language guidelines

for writing about disability (APA, 2020b).

- Bias-Free Language, “Disability” (APA, 2022)

- Disability Language Style Guide (NCDJ, 2023)

- Person-first versus Identity-first language: the discussion of person-first versus identity-first language was first applied to issues regarding people with disabilities. However, the language has been broadened to refer to other identity groups. Authors who write about identity are encouraged to use terms and descriptions that both honor and explain person-first and identity-first perspectives. Language should be selected with the understanding that the individual’s preference supersedes matters of style. In person-first language, the person is emphasized, not the disability or chronic condition. In identity-first language, the disability becomes the focus, which allows the individual to claim the disability or the chronic condition and choose their identity rather than permitting others (e.g., authors, educators, researchers) to name it or to select terms with negative implications. It is often used as an expression of cultural pride and a reclamation of a disability or chronic condition that once conferred a negative identity. It is permissible to use either approach or to mix person-first and identity-first language unless or until you know that a group clearly prefers one approach, in which case, you should use the preferred approach (APA, 2020b).

- Ability and the Carceral System

- College Students with Disabilities: Factors Influencing Growth in Academic Ability and Confidence

- Social Work Students and Mental Health (2018)

- Learning impacts reported by students living with learning challenges/disability

- Making Disability Visible in Social Work Education

Stories & Celebrations

- Disability Visibility Podcast (Pick an Episode)

- Morgans Wonderland & Inspiration Island

- Funds to Increase the number of School-Based Mental Health Services (October, 2022)

Reflection & Next Steps

- What connections did you make to the material in this section?

- Connections to other academic learning?

- Connections to your own experiences, thoughts, and/or emotions?

- Connections to current news and/or pop culture?

- What questions do you still have about the material in this chapter? What feels fuzzy, or just out of your reach?

Additional Content in LMS