2 Chapter 2: Grounding Theories, Frameworks, & Models

Who is someone in your life or in popular culture that intrigues, inspires, or enrages you?

Really!

Stop and think of someone.

I’m thinking of my friend Jeremy. Why is he like that?

Perhaps you have a friend who seems to “have it all together” or a parent who perpetually seems to be “falling apart”. Maybe a partner in work or in love sees life quite differently from you in terms of food, fashion, time, and communication. Meanwhile, there is a celebrity or political leader with whom you feel perfectly in sync. What are the forces that shape who we become in the world and what in the world can we do to make this place hospitable to the many expressions of humanity that exist here? Theories, models, and frameworks give us the foundations upon which we can layer new knowledge as we build structures of our understanding in our minds, bodies, and communities. In this chapter, you will receive some major building blocks available to anchor your understanding of human diversity and social justice.

Guiding Frameworks

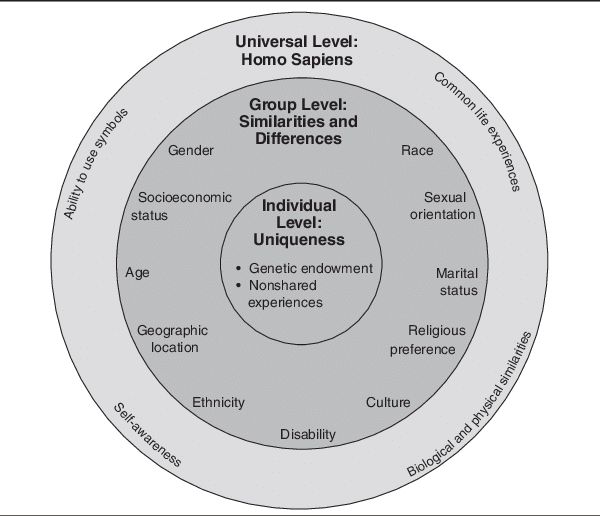

Five models/frameworks will guide the rest of this text. They include the Tripartite Model of Personal Identity, Counterintuitive Solidarity, Cultural Humility, and Intersectionality. See definitions for these terms below.

- Tripartite Model of Personal Identity: The first guiding framework comes from Doctors Derald Wing Sue, Mikal Rasheed, and Janice Rasheed who have developed a model birthed from an (unspecified) Asian axiom that all people are in some regards “like all other people”, “like no other people”, and “like some other people” (Sue, Rasheed, & Rasheed, 2015)).. The visual depiction below further illustrates the ways that all of us are defined as unique individuals, as members of broader group identities, and by virtue of universal human experiences.

-

- Example: Paola and Sophia are identical twin sisters, however, due to unequal placental sharing in utero Paola received fewer nutrients than her twin and was subsequently born at a birth weight that required immediate and ongoing medical supervision and intervention apart from the family, while Sophia was able to stay with their parents for the first week of her life. Even two humans that share DNA immediately find themselves with different access to resources based on their situatedness in their external environments (Individual). Both girls are Mexican American and will be shaped by shared food, rituals, and religious experiences over the course of their lives. This shaping will be different than if they had been born into a different ethnic identity (Group). Throughout all of their shaping, each woman will experience grief over limitations and losses because limitations and loss are fundamental aspects of the human condition (Universal).

- Counterintuitive Solidarity: to trust the intuition of oppressed people over and against one’s own gut and experience, which is proven to lead you astray when operating from a vantage point of dominance. Privileged people must do something very absurd and unnatural; they must move decisively towards [counterintuitive solidarity with] those on the margins [while] allowing the eyes of the violated to lead and guide the way (Hart, 2016).

- Example: John Robert is a fifty-year-old man who has recently learned that his 20-year-old daughter Evie is bisexual and that people often discount her sexual identity as a phase or “attempt to get attention”. There was a time in J.R.’s life when he believed that bisexuality was a myth but after reading, watching, and listening to many stories of queer individuals, he understood that 1.) when someone shares the truth about their sexual identity it is important to assume that they are the expert of their own bodies, 2.) that they might feel scared to share for fear of judgment/loss and 3.) that it is best not to suggest that someone who is bisexual just forget or abandon their attraction for individuals of the same sex and/or gender. Because John Robert trusted the voices of queer people in his life and in the content he consumed, he was able to tell his daughter that he loved her, accepted her, and appreciated her vulnerability to share something so personal with him.

- Cultural Humility: a lifelong process of critical self-reflection whereby an individual not only learns about another’s culture but rather starts with an examination of their own beliefs and cultural identities. Additionally, cultural humility requires mitigating power imbalances and ensuring institutional accountability. Watch the story of the development of this term below (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia,1998).

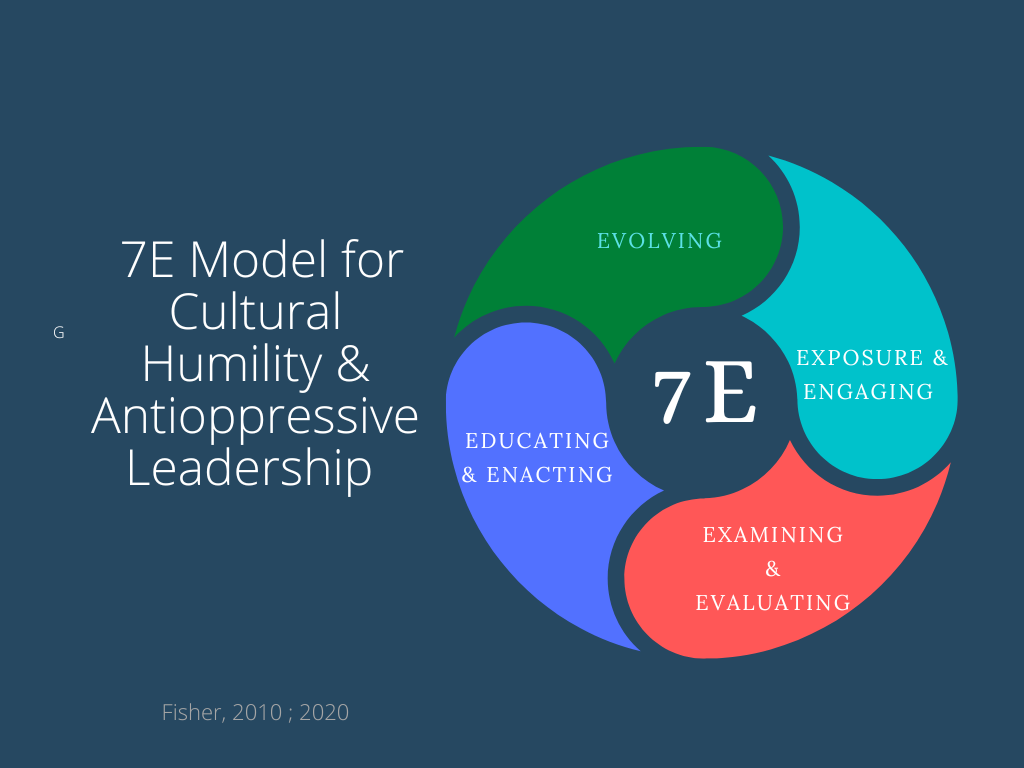

Students often express curiosity about how to establish the practice of cultural humility in everyday existence. The 7E model (Fisher, 2021) offers a set of overlapping multi-directional experiences that encourage lifelong critical self-reflection, as well as opportunities for challenging power differentials in communities, as well as holding institutions accountable for their actions (and inaction). The following image and description of the model are excerpted from An Experiential Model for Cultivating Cultural Humility and Embodying Antiracist Action In and Outside the Social Work Classroom (Fisher, 2021).

“Introduction & Structure”

The 7E model for Cultural Humility and Antioppressive Action moves from intrapersonal work connected to the “lifelong learning and critical self-reflection” tenet of cultural humility and moves increasingly into interpersonal and institutional level action in keeping with the tenets of “challenging power imbalances” and “holding institutions accountable” (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998 p.118).

Step-based models can easily become cemented in individual minds and collective consciousness as linear, hierarchical, and static—a very western, “objective” manner of engaging information when, in truth, much of life and learning tend to be interconnected, dynamic and cyclical (if any structurally reliable pattern exists at all). For that reason, the 7E model uses the word “experience” rather than “step” to describe states of awareness and action. Experiences sometimes happen in the order described, and at other times they happen concurrently or partially concurrently.

“Encounter” Experiences: Exposure & Engaging

Encounter experiences are any experiences (whether incidental or intentional) in which an individual has occasion to observe, consume, or participate in an activity that is foreign to their own intersectional identities and experiences. An easy way to identify such experiences is to consider what you are reading, watching, listening to and/or attending.

Reflective Experiences: Examining & Evaluating

Reflective Experiences can happen before, during, or after Encounter Experiences and are characterized by examining thoughts, feelings, and actions in anticipation of, or in response to, engaging with new people, content, and/or experiences. Initially, “examination” is meant to be practiced as a non-judgmental self-observation, simply noticing changes in the three b’s “body” (ex: sweat, tears), “brain” (ex: judgments, defense mechanisms) and “behavior” (ex: yelling, leaving).

Interventive Experiences: Enacting & Educating

While Encounter and Reflective experiences primarily help students develop the “lifelong learning” and “critical self-reflection” tenets of cultural humility, interventive experiences move into the more actively antiracist tenets of challenging power imbalances and holding institutions accountable. Educating & enacting change means practicing microresistance in interpersonal relationships and macroresistance strategies when the systems and institutions of which we are a part are guilty of dominant-group supremacy in policies, procedures, or practices.

Maintenance Experience: Evolving

Any model must have a maintenance mechanism and any antiracist model must honor the requirement to evolve because systems will always continue to find ways to evade and pervert justice. Truly humble and anti-racist activists must be agile enough to take in new data, learn fresh terminology, and employ emergent strategies.”

Take a Break, and then begin again…

Critical Theories

Critical Race Theory: intellectual and social movement and loosely organized framework of legal analysis based on the premise that race is not a natural, biologically grounded feature of physically distinct subgroups of human beings but a socially constructed (culturally invented) category that is used to oppress and exploit people of color. Critical race theorists hold that racism is inherent in the law and legal institutions of the United States insofar as they function to create and maintain social, economic, and political inequalities between whites and nonwhites, especially African Americans. Critical race theorists are generally dedicated to applying their understanding of the institutional or structural nature of racism to the concrete (if distant) goal of eliminating all race-based and other unjust hierarchies. (Encyclopedia Brittanica, 2022)

Social Work Researcher Ashley Daftary (2020) describes 8 tenets of critical race theory as summarized below. Examples included are from this text’s author, not Daftary:

- Racism is an embedded facet of society (specifically in the law and legal systems).

- Example: Disproportionate sentences for crack and powder cocaine result in more and longer sentences for Black individuals than their White counterparts despite legislation passed to try and remedy the laws that make such unfair sentencing possible. Justice Action Network, 2022)

- Race is a social construction (rather than a biological reality).

- Example: The “one drop rule” was a metric used in the American South to determine how much African American blood was required for someone to be deemed a person of color (PBS, 2014)

- Interest Convergence or Material Determinism is the tendency for the dominant groups to participate in antiracist ways when and insofar as doing so has social/financial benefits for the dominant group.

- Example: In 2020, amidst racial reckonings and reawakenings, many companies developed merchandise with BLM-related messaging. This created profit opportunities and potentially positive advertising for these companies at a moment when many desired to show alignment with the so-called BIPOC communities.

- Objection to Ahistoricism which tells the narrative of history from the vantage point of dominant groups

- Example: Some textbooks describe slavery as indentured servitude and emphasize positive relationships between slaveholders and enslaved people rather than accurately portraying the atrocities of slavery.

- Counterstorytelling is the act of making space for black and brown people to narrate their own experiences and to have that narration centered. This is in contrast to supremacist centering of whiteness and supremacist centering of facts and figures over voice and experience.

- Example: A community health center has a panel about mental health and prioritizes inviting Black and Latino psychologists and social workers rather than exclusively white practitioners. This results in showcasing different approaches, aesthetics, terminology, tone, and case studies than would have otherwise been highlighted.

- Critique of Classical Liberalism: This critique suggests that traditional legal scholarship has believed in color-blind approaches rather than making race a central component of legal decision-making.

- Intersectionality is an important lens to capture the full range of experiences that Black individuals inhabit. for example, some African American individuals are also women, older adults, disabled, queer, religious minorities, undocumented immigrants, and/or socioeconomically distressed.

- Example: a trans black woman whose highest education is 10th grade has different health outcomes than a biracial CIS black man with advanced degrees from Harvard and Yale.

Related critical theories include LatCrit, AsianCrit, QueerCrit, FemCrit & QuanCrit. Baylor readers find critical research here. Others see your instructor’s LMS for more articles.

Intersectionality

As discussed in Chapter 1, Intersectionality is “the complex, cumulative way in which the effects of multiple forms of discrimination (such as racism, sexism, and classism) combine, overlap, or intersect especially in the experiences of marginalized individuals or groups to produce and sustain complex inequities. Kimberlé Crenshaw introduced the theory of intersectionality in a paper for the University of Chicago Legal Forum (Crenshaw, 1989), the idea that when it comes to thinking about how inequalities persist, categories like gender, race, and class are best understood as overlapping and mutually constitutive rather than isolated and distinct” (Grzanka et al., 2017, 2020). If you have not already, watch Dr. Crenshaw discuss and describe intersectionality below!

More Reading, Watching and Listening:

References

Daftary, A. M. H. (2018). Critical race theory: An effective framework for social work research. Journal of Ethnic &

Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 29(9), 439-454. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2018.1534223

Fisher, K. (2021). An experiential model for cultivating cultural humility and embodying antiracist action in and outside the social work classroom. Advances in Social Work 21(2/3), 690-707. https://doi.org/10.18060/24184