Think of a time when someone was singled out in a group as “other” in some way or another. How was that “othering” communicated? How did it make you feel at the time? How does it make you feel now?

Think of a time when someone was singled out in a group as “other” in some way or another. How was that “othering” communicated? How did it make you feel at the time? How does it make you feel now?

- What is your current understanding of the term microaggression?

- Do you believe (or know) you have ever experienced one?

- Which strategies have you used (or would you use) if you were a bystander to a microaggression?

Interpersonal Relationships & Power

Think about your family of origin or a peer group that you remember well from your youth. Though there may or may not have been a formal hierarchical power structure, there was likely some way of predicting whose requests/needs/desires/commands would be centered in a given circumstance. Perhaps there were stated rules, like “curfew is at midnight” or “no dating your friend’s former love interest”. Perhaps there were also unspoken rules like “no one talks to Mom before 9 am” or “no one disagrees with John”. Interpersonal power is often underacknowledged in personal and professional relationships but the impact can be profound.

Types of Power

Sociologists French and Raven identified five bases of power: coercive, reward, legitimate, expert, and referent. Information power was added as a sixth category years later. The chart below explains a little about each category.

| French And Raven’s Bases of Power (1959; 1965) | Definitions |

| Legitimate | Power enjoyed because an individual has the formal right to make demands, and to expect others to be compliant and obedient |

| Reward | Power enjoyed because an individual can compensate another for compliance/agreement. |

| Expert | Power enjoyed because an individual has high-level skills and knowledge in a certain/are or topic |

| Referent | Power enjoyed because an individual has a right to respect/deference due to perceived attractiveness and worthiness |

| Coercive | Power enjoyed because an individual can punish others for any non-compliance |

| Informational | Power enjoyed because an individual has the ability to control the information that others need to accomplish something |

Microaggressive Theory

I often think of sibling relationships when I try to find a metaphor for microaggressions. As the youngest child in my family of origin, I am all too familiar with the sly ways that siblings shape situations in ways that are subtle and hard to catch. Perhaps an older brother whispers incessantly into a younger sister’s ear, “I love you, I love you, I love you,” in a very nasally, performative voice. When the younger sibling complains to the supervising adult about the situation, the older brother says, “I was just telling her how much, I love her. What’s wrong with that?”

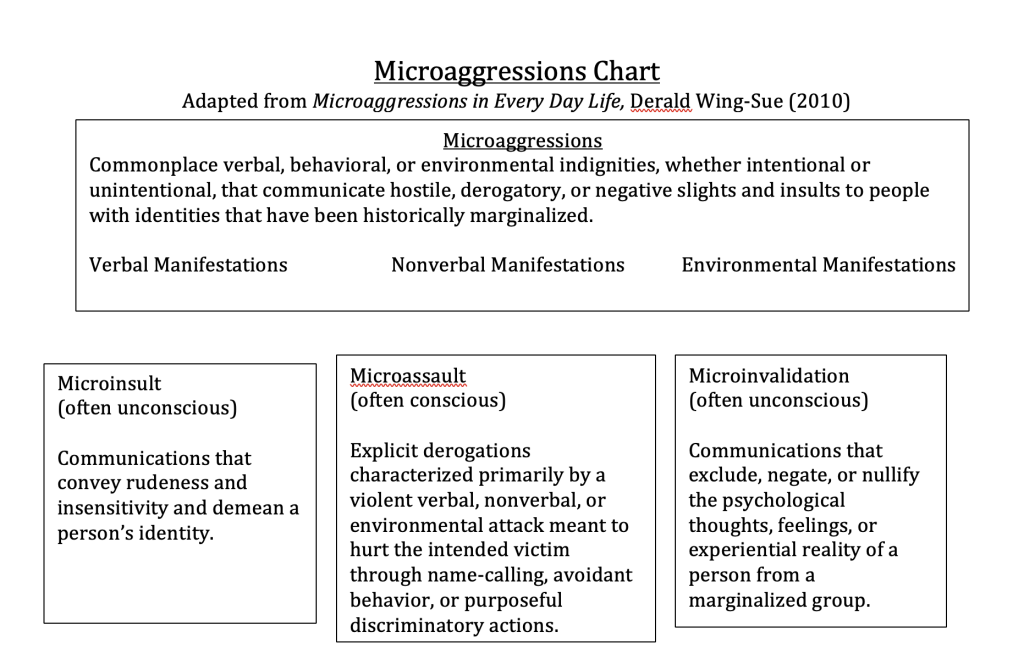

Sometimes, the responsible adult sees through the grimy tactics of the older, often larger sibling, and at other times, they might tell the little sister to stop being so sensitive and whiny. So it is with microaggressions. They can be slippery, slimy words/behaviors and whether intentional or unintentional the phenomena of living with identities that are often microagressed has been referred to as “death by a 1000 cuts”. One small cut might seem inconsequential, but it is the everyday, continuous experience of being belittled, ignored, or mischaracterized that can become injurious, if not deadly. Microaggressions are defined and typed by Derald Wing Sue in the chart below. Sue has built on the work of Dr. Chester Pierce who first coined the term in the 1970s.

-

- Take a look at a few examples in this video (some explicit language) and/or in the Microaggressions Encyclopedia!

In recent years there has been some pushback on the term microaggression by scholars such as Ibram X Kendi (2019) due to the real or perceived sense that “micro” states or implies that these interactions are small or minor in impact. In reality, it is clear that microaggressions have major structural, interpersonal, and intrapersonal impacts. Kendi says he prefers the term “abuse” and other authors have used terms such as Subtle Acts of Exclusion (SAE) (Jana, 2020). One way to reconsider the “micro” part of the word microaggression is to consider that they are acts that tend to happen primarily interpersonally–the “micro” level of interactions. An exception to this might be environmental manifestations of microaggressions. What do you think about the term microaggression?

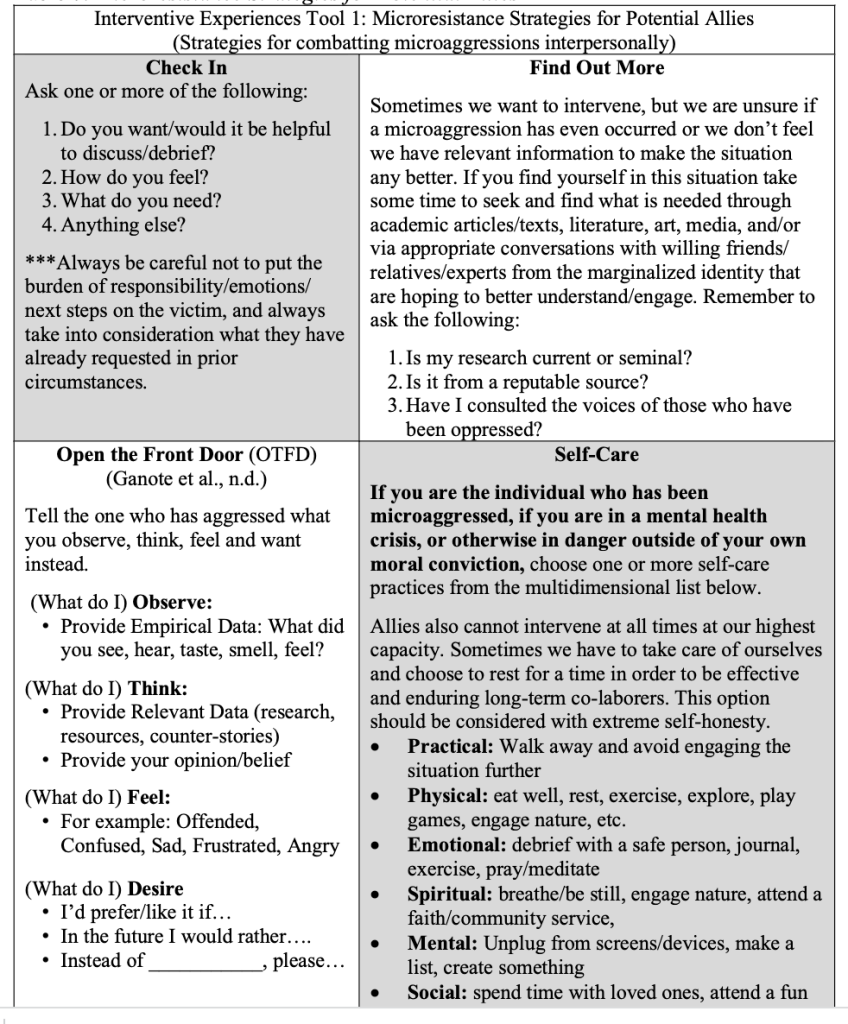

Microresistance Strategies: There are many ways that scholars have described the attempts to combat microaggressions by self-advocates and aspiring allies. See a few below.

- Microinterventions: unintentional or intentional words or deeds that validate the targets’ experiences, affirm their racial identity, and offer encouragement, support, and reassurance that the target is not alone (Sue et al., 2019).

- Microresistance: small-scale individual or collaborative efforts that empower targeted people and allies to cope with, respond to, and/or challenge microaggressions with the goal of disrupting systems of oppression as they unfold in everyday life, thereby creating more inclusive institutions (Chung, Ganote, Souza, 2016)

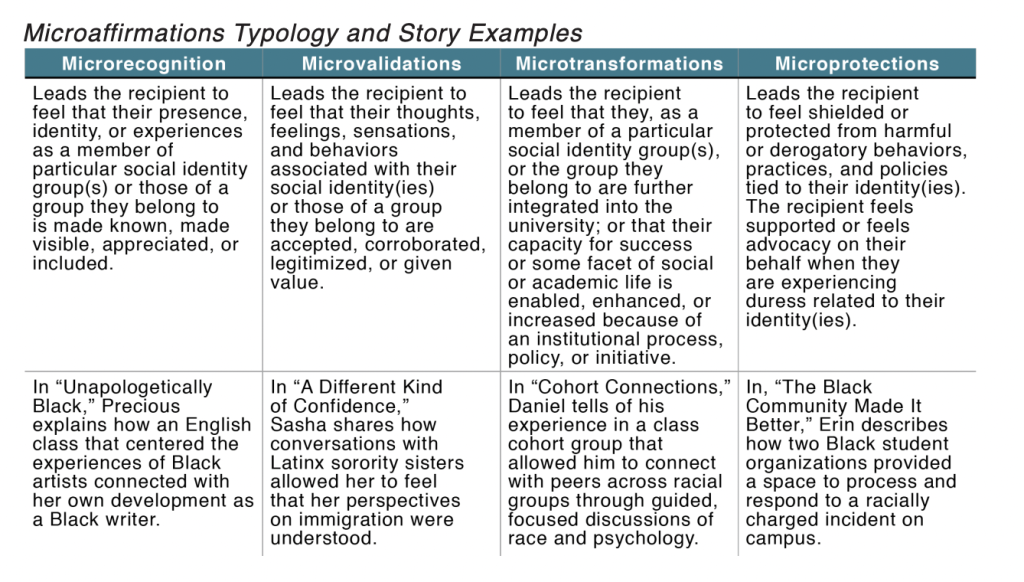

- Microaffirmations: tiny acts of opening doors to opportunity, gestures of inclusion and caring, and graceful acts of listening (Rowe, 2008)

Rosalie Rolon-Dow (2019) has created a microaffirmations typology that can be a helpful tool for understanding this type of microintervention more thoroughly.

The author of this text has created 4 categories of microresistance that self-advocates and aspiring allies can use to intervene when microaggressions occur.

Looking at the chart above, how many of these microinterventions have you tried? Which of them seems the most natural to you? Which could be a “comfortably uncomfortable” opportunity for you to try in the future?

References

Fisher, K. (2021). An experiential model for cultivating cultural humility and embodying antiracist action in and outside the social work classroom. Advances in Social Work 21(2/3), 690-707. https://doi.org/10.18060/24184

Ganote, C., Souza, T., & Cheung, F. (n.d.). Microresistance and ally development: Powerful antidotes to microaggressions. https://www.unomaha.edu/faculty-support/teaching-excellence/microaggressions-handout.pdf\

French, J. R. P., Jr., & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power (pp. 150–167).Univer. Michigan.

Rolón-Dow, R. (2019). Stories of microaggressions and microaffirmations: a framework for listening to campus racial climate. currents, 1(1), 64-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/currents.17387731.0001.106

Rowe, Mary. (2008). “Micro-affirmations & Micro-inequities.” Journal of the International Ombudsman Association. 1(1)

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271-286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.62.4.271

Sue, D. W., Rasheed, M. N., & Rasheed, J. M. (2016). Multicultural social work practice: A competency-based approach to diversity and social justice (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.