Ch. 10: Personality

Consider two brothers. One of these siblings will grow up to become a world leader. The other will struggle with alcohol and drugs, eventually spending time in jail. What about each of their personalities propelled them to take the path they did?

Three months before William Jefferson Blythe III was born, his father died in a car accident. He was raised by his mother, Virginia Dell, and grandparents, in Hope, Arkansas. When he turned 4, his mother married Roger Clinton, Jr., an alcoholic who was physically abusive to William’s mother. Six years later, Virginia gave birth to another son, Roger. William, who later took the last name Clinton from his stepfather, became the 42nd president of the United States. While Bill Clinton was making his political ascendance, his half-brother, Roger Clinton, was arrested numerous times for drug charges, including possession, conspiracy to distribute cocaine, and driving under the influence, serving time in jail. Two brothers, raised by the same people, took radically different paths in their lives. Why did they make the choices they did? What internal forces shaped their decisions? Personality psychology can help us answer these questions and more.

What is personality?

When we observe people around us, one of the first things that strikes us is how different people are from one another. Some people are very talkative while others are very quiet. Some are active whereas others are couch potatoes. Some worry a lot, others almost never seem anxious. Each time we use one of these words, words like “talkative,” “quiet,” “active,” or “anxious,” to describe those around us, we are talking about a person’s personality—the characteristic ways that people differ from one another. Personality psychologists try to describe and understand these differences.

Learning Objectives

- Define personality and describe early theories about personality development

Personality refers to the long-standing traits and patterns that propel individuals to consistently think, feel, and behave in specific ways. Our personality is what makes us unique individuals. Each person has an idiosyncratic pattern of enduring, long-term characteristics and a manner in which they interact with other individuals and the world around them. Our personalities are thought to be long term, stable, and not easily changed. The word personality comes from the Latin word persona. In the ancient world, a persona was a mask worn by an actor. While we tend to think of a mask as being worn to conceal one’s identity, the theatrical mask was originally used to either represent or project a specific personality trait of a character (Figure 1).

Historical Perspectives

The concept of personality has been studied for at least 2,000 years, beginning with Hippocrates in 370 BCE (Fazeli, 2012). Hippocrates theorized that personality traits and human behaviors are based on four separate temperaments associated with four fluids (“humors”) of the body: choleric temperament (yellow bile from the liver), melancholic temperament (black bile from the kidneys), sanguine temperament (red blood from the heart), and phlegmatic temperament (white phlegm from the lungs) (Clark & Watson, 2008; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985; Lecci & Magnavita, 2013; Noga, 2007). Centuries later, the influential Greek physician and philosopher Galen built on Hippocrates’s theory, suggesting that both diseases and personality differences could be explained by imbalances in the humors and that each person exhibits one of the four temperaments. For example, the choleric person is passionate, ambitious, and bold; the melancholic person is reserved, anxious, and unhappy; the sanguine person is joyful, eager, and optimistic; and the phlegmatic person is calm, reliable, and thoughtful (Clark & Watson, 2008; Stelmack & Stalikas, 1991). Galen’s theory was prevalent for over 1,000 years and continued to be popular through the Middle Ages.

In 1780, Franz Gall, a German physician, proposed that the distances between bumps on the skull reveal a person’s personality traits, character, and mental abilities (Figure 3). According to Gall, measuring these distances revealed the sizes of the brain areas underneath, providing information that could be used to determine whether a person was friendly, prideful, murderous, kind, good with languages, and so on. Initially, phrenology was very popular; however, it was soon discredited for lack of empirical support and has long been relegated to the status of pseudoscience (Fancher, 1979).

In the centuries after Galen, other researchers contributed to the development of his four primary temperament types, most prominently Immanuel Kant (in the 18th century) and psychologist Wilhelm Wundt (in the 19th century) (Eysenck, 2009; Stelmack & Stalikas, 1991; Wundt, 1874/1886) (Figure 3). Kant agreed with Galen that everyone could be sorted into one of the four temperaments and that there was no overlap between the four categories (Eysenck, 2009). He developed a list of traits that could be used to describe the personality of a person from each of the four temperaments. However, Wundt suggested that a better description of personality could be achieved using two major axes: emotional/nonemotional and changeable/unchangeable. The first axis separated strong from weak emotions (the melancholic and choleric temperaments from the phlegmatic and sanguine). The second axis divided the changeable temperaments (choleric and sanguine) from the unchangeable ones (melancholic and phlegmatic) (Eysenck, 2009).

Sigmund Freud’s psychodynamic perspective of personality was the first comprehensive theory of personality, explaining a wide variety of both normal and abnormal behaviors. According to Freud, unconscious drives influenced by sex and aggression, along with childhood sexuality, are the forces that influence our personality. Freud attracted many followers who modified his ideas to create new theories about personality. These theorists, referred to as neo-Freudians, generally agreed with Freud that childhood experiences matter, but they reduced the emphasis on sex and focused more on the social environment and effects of culture on personality. The perspective of personality proposed by Freud and his followers was the dominant theory of personality for the first half of the 20th century.

Other major theories then emerged, including the learning, humanistic, biological, evolutionary, trait, and cultural perspectives. In this module, we will explore these various perspectives on personality in depth.

Link to Learning

View this video for a brief overview of some of the psychological perspectives on personality.

Think It Over

- How would you describe your own personality? Do you think that friends and family would describe you in much the same way? Why or why not?

- How would you describe your personality in an online dating profile?

- What are some of your positive and negative personality qualities? How do you think these qualities will affect your choice of career?

Explaining Personality

There are many approaches that work to explain personality. In this section, you’ll learn about the behavioral, humanistic, biological, trait, and cultural perspectives.

Watch It

Watch this video for an overview about the main philosophical approaches to studying personality:

You can view the transcript for “What’s Personality All About” here (opens in new window).

Learning Approaches to Personality

The learning approaches focus only on observable behavior. This illustrates one significant advantage of the learning approaches to personality over psychodynamics: Because learning approaches involve observable, measurable phenomena, they can be scientifically tested.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the learning perspective on personality, including the concepts of reciprocal determinism, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the person-situation debate

Behavioral Perspective

Behaviorists do not believe in biological determinism: They do not see personality traits as inborn. Instead, they view personality as significantly shaped by the reinforcements and consequences outside of the organism. In other words, people behave in a consistent manner based on prior learning. B. F. Skinner, a strict behaviorist, believed that the environment was solely responsible for all behavior, including the enduring, consistent behavior patterns studied by personality theorists.

As you may recall from your study on the psychology of learning, Skinner proposed that we demonstrate consistent behavior patterns because we have developed certain response tendencies (Skinner, 1953). In other words, we learn to behave in particular ways. We increase the behaviors that lead to positive consequences, and we decrease the behaviors that lead to negative consequences. Skinner disagreed with Freud’s idea that personality is fixed in childhood. He argued that personality develops over our entire life, not only in the first few years. Our responses can change as we come across new situations; therefore, we can expect more variability over time in personality than Freud would anticipate. For example, consider a young woman, Greta, a risk-taker. She drives fast and participates in dangerous sports such as hang gliding and kiteboarding. But after she gets married and has children, the system of reinforcements and punishments in her environment changes. Speeding and extreme sports are no longer reinforced, so she no longer engages in those behaviors. Greta now describes herself as a cautious person.

Social-Cognitive Perspective

Albert Bandura agreed with Skinner that personality develops through learning. He disagreed, however, with Skinner’s strict behaviorist approach to personality development, because he felt that thinking and reasoning are important components of learning. He presented a social-cognitive theory of personality that emphasizes both learning and cognition as sources of individual differences in personality. In social-cognitive theory, the concepts of reciprocal determinism, observational learning, and self-efficacy all play a part in personality development.

Reciprocal Determinism

In contrast to Skinner’s idea that the environment alone determines behavior, Bandura (1990) proposed the concept of reciprocal determinism, in which cognitive processes, behavior, and context all interact, each factor influencing and being influenced by the others simultaneously (Figure 5). Cognitive processes refer to all characteristics previously learned, including beliefs, expectations, and personality characteristics. Behavior refers to anything that we do that may be rewarded or punished. Finally, the context in which the behavior occurs refers to the environment or situation, which includes rewarding/punishing stimuli.

Consider, for example, that you’re at a festival and one of the attractions is bungee jumping from a bridge. Do you do it? In this example, the behavior is bungee jumping. Cognitive factors that might influence this behavior include your beliefs and values, and your past experiences with similar behaviors. Finally, context refers to the reward structure for the behavior. According to reciprocal determinism, all of these factors are in play.

Observational Learning

Bandura’s key contribution to learning theory was the idea that much learning is vicarious. We learn by observing someone else’s behavior and its consequences, which Bandura called observational learning. He felt that this type of learning also plays a part in the development of our personality. Just as we learn individual behaviors, we learn new behavior patterns when we see them performed by other people or models. Drawing on the behaviorists’ ideas about reinforcement, Bandura suggested that whether we choose to imitate a model’s behavior depends on whether we see the model reinforced or punished. Through observational learning, we come to learn what behaviors are acceptable and rewarded in our culture, and we also learn to inhibit deviant or socially unacceptable behaviors by seeing what behaviors are punished.

We can see the principles of reciprocal determinism at work in observational learning. For example, personal factors determine which behaviors in the environment a person chooses to imitate, and those environmental events in turn are processed cognitively according to other personal factors. One person may experience receiving attention as reinforcing, and that person may be more inclined to imitate behaviors such as boasting when a model has been reinforced. For others, boasting may be viewed negatively, despite the attention that might result—or receiving heightened attention may be perceived as being scrutinized. In either case, the person may be less likely to imitate those behaviors even though the reasons for not doing so would be different.

Self-Efficacy

Bandura (1977, 1995) has studied a number of cognitive and personal factors that affect learning and personality development, and most recently has focused on the concept of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is our level of confidence in our own abilities, developed through our social experiences. Self-efficacy affects how we approach challenges and reach goals. In observational learning, self-efficacy is a cognitive factor that affects which behaviors we choose to imitate as well as our success in performing those behaviors.

People who have high self-efficacy believe that their goals are within reach, have a positive view of challenges, see them as tasks to be mastered, develop a deep interest in and strong commitment to the activities in which they are involved, and quickly recover from setbacks. Conversely, people with low self-efficacy avoid challenging tasks because they doubt their ability to be successful, tend to focus on failure and negative outcomes, and lose confidence in their abilities if they experience setbacks. Feelings of self-efficacy can be specific to certain situations. For instance, a student might feel confident in her ability in English class but much less so in math class.

Julian Rotter and Locus of Control

Julian Rotter (1966) proposed the concept of locus of control, another cognitive factor that affects learning and personality development. Distinct from self-efficacy, which involves our belief in our own abilities, locus of control refers to our beliefs about the power we have over our lives. In Rotter’s view, people possess either an internal or an external locus of control (Figure 6). Those of us with an internal locus of control (“internals”) tend to believe that most of our outcomes are the direct result of our efforts. Those of us with an external locus of control (“externals”) tend to believe that our outcomes are outside of our control. Externals see their lives as being controlled by other people, luck, or chance. For example, say you didn’t spend much time studying for your psychology test and went out to dinner with friends instead. When you receive your test score, you see that you earned a D. If you possess an internal locus of control, you would most likely admit that you failed because you didn’t spend enough time studying and decide to study more for the next test. On the other hand, if you possess an external locus of control, you might conclude that the test was too hard and not bother studying for the next test because you figure you will fail it anyway. Researchers have found that people with an internal locus of control perform better academically, achieve more in their careers, are more independent, are healthier, are better able to cope, and are less depressed than people who have an external locus of control (Benassi et al., 1988; Lefcourt, 1982; Maltby et al., 2007; Whyte, 1977, 1978, 1980).

Link to Learning

Take the Locus of Control questionnaire. A low score on this questionnaire indicates an internal locus of control, and a high score indicates an external locus of control.

Think It Over

Do you have an internal or an external locus of control? Provide examples to support your answer.

Humanistic Approaches to Personality

Learning Objectives

- Explain the contributions of humanists Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers to personality development

As the “third force” in psychology, humanism is touted as a reaction both to the pessimistic determinism of psychoanalysis, with its emphasis on psychological disturbance, and to the behaviorists’ view of humans passively reacting to the environment, which has been criticized as making people out to be personality-less robots. It does not suggest that psychoanalytic, behaviorist, and other points of view are incorrect but argues that these perspectives do not recognize the depth and meaning of human experience, and fail to recognize the innate capacity for self-directed change and transforming personal experiences. This perspective focuses on how healthy people develop. One pioneering humanist, Abraham Maslow, studied people who he considered to be healthy, creative, and productive, including Albert Einstein, Eleanor Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and others. Maslow (1950, 1970) found that such people share similar characteristics, such as being open, creative, loving, spontaneous, compassionate, concerned for others, and accepting of themselves. When you studied motivation, you learned about one of the best-known humanistic theories, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, in which Maslow proposes that human beings have certain needs in common and that these needs must be met in a certain order. The highest need is the need for self-actualization, which is the achievement of our fullest potential. Maslow differentiated between needs that motivate us to fulfill something that is missing and needs that inspire us to grow. He believed that many emotional and behavioral concerns arise as a result of failing to meet these hierarchical needs.

Another humanistic theorist was Carl Rogers. One of Rogers’s main ideas about personality regards self-concept, our thoughts and feelings about ourselves. How would you respond to the question, “Who am I?” Your answer can show how you see yourself. If your response is primarily positive, then you tend to feel good about who you are, and you see the world as a safe and positive place. If your response is mainly negative, then you may feel unhappy with who you are. Rogers further divided the self into two categories: the ideal self and the real self. The ideal self is the person that you would like to be; the real self is the person you actually are. Rogers focused on the idea that we need to achieve consistency between these two selves. We experience congruence when our thoughts about our real self and ideal self are very similar—in other words, when our self-concept is accurate.

Unconditional Positive Regard

High congruence leads to a greater sense of self-worth and a healthy, productive life. Parents can help their children achieve this by giving them unconditional positive regard, or unconditional love. According to Rogers (1980), “As persons are accepted and prized, they tend to develop a more caring attitude towards themselves” (p. 116). People raised in an environment of unconditional positive regard, in which no preconceived conditions of worth are present, have the opportunity to fully actualize. When people are raised in an environment of conditional positive regard, in which worth and love are only given under certain conditions, they must match or achieve those conditions in order to receive the love or positive regard they yearn for. Their ideal self is thereby determined by others based on these conditions, and they are forced to develop outside of their own true actualizing tendency; this contributes to incongruence and a greater gap between the real self and the ideal self. Both Rogers’s and Maslow’s theories focus on individual choices and do not believe that biology is deterministic.

Rogers based his theories of personality development on humanistic psychology and theories of subjective experience. He believed that everyone exists in a constantly changing world of experiences that they are at the center of. A person reacts to changes in their phenomenal field, which includes external objects and people as well as internal thoughts and emotions.

Rogers believed that all behavior is motivated by self-actualizing tendencies, which drive a person to achieve at their highest level. As a result of their interactions with the environment and others, an individual forms a structure of the self or self-concept—an organized, fluid, conceptual pattern of concepts and values related to the self. If a person has a positive self-concept, they tend to feel good about who they are and often see the world as a safe and positive place. If they have a negative self-concept, they may feel unhappy with who they are.

Achieving “The Good Life”

Rogers described life in terms of principles rather than stages of development. These principles exist in fluid processes rather than static states. He claimed that a fully functioning person would continually aim to fulfill their potential in each of these processes, achieving what he called “the good life.” These people would allow personality and self-concept to emanate from experience. He found that fully functioning individuals had several traits or tendencies in common:

- A growing openness to experience–they move away from defensiveness.

- An increasingly existential lifestyle–living each moment fully, rather than distorting the moment to fit personality or self-concept.

- Increasing organismic trust–they trust their own judgment and their ability to choose behavior that is appropriate for each moment.

- Freedom of choice–they are not restricted by incongruence and are able to make a wide range of choices more fluently. They believe that they play a role in determining their own behavior and so feel responsible for their own behavior.

- Higher levels of creativity–they will be more creative in the way they adapt to their own circumstances without feeling a need to conform.

- Reliability and constructiveness–they can be trusted to act constructively. Even aggressive needs will be matched and balanced by intrinsic goodness in congruent individuals.

- A rich full life–they will experience joy and pain, love and heartbreak, fear and courage more intensely.

Criticisms of Rogers’ Theories

Like Maslow’s theories, Rogers’ were criticized for their lack of empirical evidence used in research. The holistic approach of humanism allows for a great deal of variation but does not identify enough constant variables to be researched with true accuracy. Psychologists also worry that such an extreme focus on the subjective experience of the individual does little to explain or appreciate the impact of society on personality development.

Think It Over

Respond to the question, “Who am I?” Based on your response, do you have a negative or a positive self-concept? What are some experiences that led you to develop this particular self-concept?

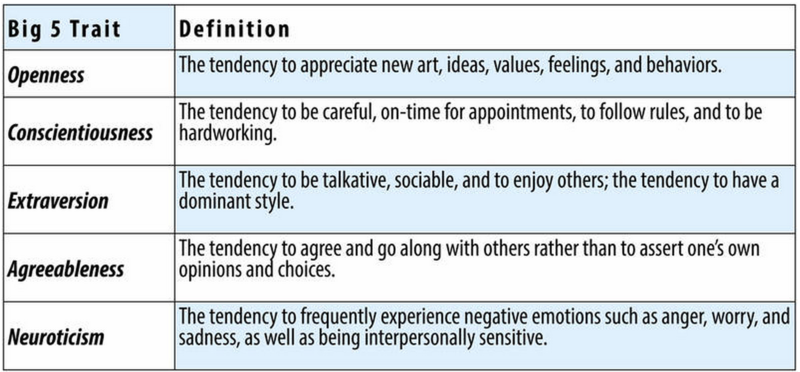

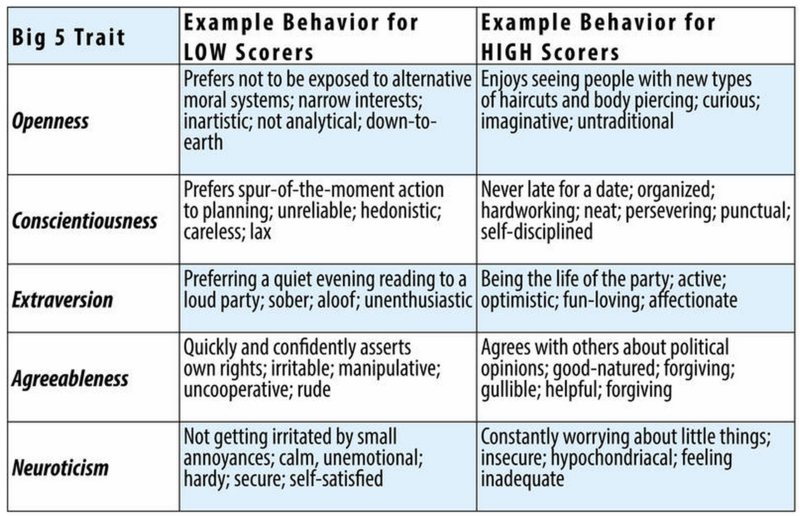

Trait Approaches to Personality

Personality traits reflect people’s characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Personality traits imply consistency and stability—someone who scores high on a specific trait like extraversion is expected to be sociable in different situations and over time. Thus, trait psychology rests on the idea that people differ from one another in terms of where they stand on a set of basic trait dimensions that persist over time and across situations. The most widely used system of traits is called the Five-Factor Model. This system includes five broad traits that can be remembered with the acronym OCEAN: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Each of the major traits from the Big Five can be divided into facets to give a more fine-grained analysis of someone’s personality. In addition, some trait theorists argue that there are other traits that cannot be completely captured by the Five-Factor Model. Critics of the trait concept argue that people do not act consistently from one situation to the next and that people are very influenced by situational forces. Thus, one major debate in the field concerns the relative power of people’s traits versus the situations in which they find themselves as predictors of their behavior.

Learning Objectives

- List and describe the “Big Five” (“OCEAN”) personality traits that comprise the Five-Factor Model of personality, including both a low and high example.

- Explain a critique of the personality-trait concept.

- Describe in what ways personality traits may be manifested in everyday behavior.

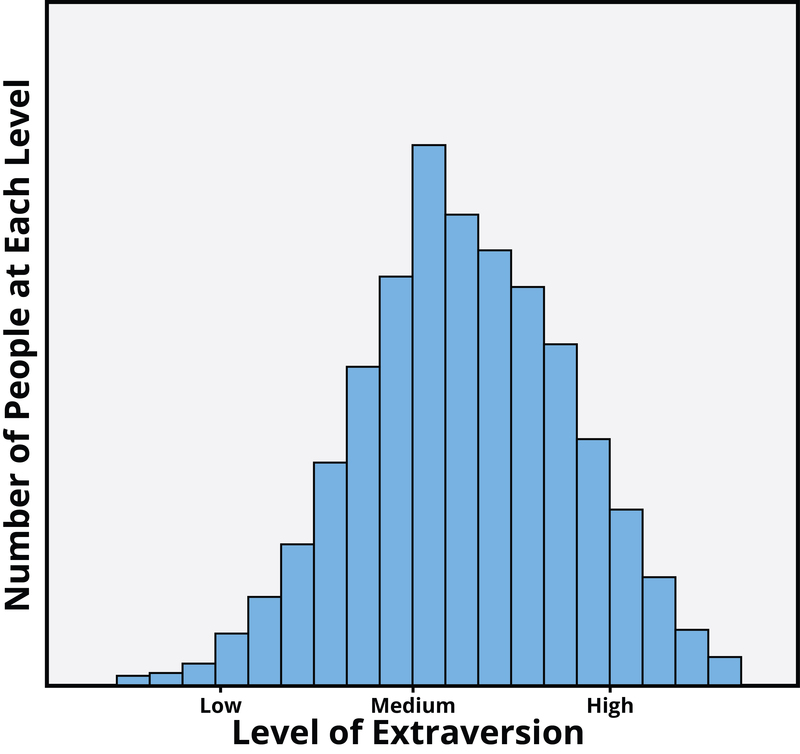

An important feature of personality traits is that they reflect continuous distributions rather than distinct personality types. This means that when personality psychologists talk about Introverts and Extraverts, they are not really talking about two distinct types of people who are completely and qualitatively different from one another. Instead, they are talking about people who score relatively low or relatively high along a continuous distribution. In fact, when personality psychologists measure traits like extraversion, they typically find that most people score somewhere in the middle, with smaller numbers showing more extreme levels. The figure below shows the distribution of extraversion scores from a survey of thousands of people. As you can see, most people report being moderately, but not extremely, extraverted, with fewer people reporting very high or very low scores.

There are three criteria that are characterize personality traits: (1) consistency, (2) stability, and (3) individual differences.

- To have a personality trait, individuals must be somewhat consistent across situations in their behaviors related to the trait. For example, if they are talkative at home, they tend also to be talkative at work.

- Individuals with a trait are also somewhat stable over time in behaviors related to the trait. If they are talkative, for example, at age 30, they will also tend to be talkative at age 40.

- People differ from one another on behaviors related to the trait. Using speech is not a personality trait and neither is walking on two feet—virtually all individuals do these activities, and there are almost no individual differences. But people differ on how frequently they talk and how active they are, and thus personality traits such as Talkativeness and Activity Level do exist.

A challenge of the trait approach was to discover the major traits on which all people differ. Scientists for many decades generated hundreds of new traits, so that it was soon difficult to keep track and make sense of them. For instance, one psychologist might focus on individual differences in “friendliness,” whereas another might focus on the highly related concept of “sociability.” Scientists began seeking ways to reduce the number of traits in some systematic way and to discover the basic traits that describe most of the differences between people.

The way that Gordon Allport and his colleague Henry Odbert approached this was to search the dictionary for all descriptors of personality (Allport & Odbert, 1936). Their approach was guided by the lexical hypothesis, which states that all important personality characteristics should be reflected in the language that we use to describe other people. Therefore, if we want to understand the fundamental ways in which people differ from one another, we can turn to the words that people use to describe one another. So if we want to know what words people use to describe one another, where should we look? Allport and Odbert looked in the most obvious place—the dictionary. Specifically, they took all the personality descriptors that they could find in the dictionary (they started with almost 18,000 words but quickly reduced that list to a more manageable number) and then used statistical techniques to determine which words “went together.” In other words, if everyone who said that they were “friendly” also said that they were “sociable,” then this might mean that personality psychologists would only need a single trait to capture individual differences in these characteristics. Statistical techniques were used to determine whether a small number of dimensions might underlie all of the thousands of words we use to describe people.

The Five-Factor Model of Personality

Research that used the lexical approach showed that many of the personality descriptors found in the dictionary do indeed overlap. In other words, many of the words that we use to describe people are synonyms. Thus, if we want to know what a person is like, we do not necessarily need to ask how sociable they are, how friendly they are, and how gregarious they are. Instead, because sociable people tend to be friendly and gregarious, we can summarize this personality dimension with a single term. Someone who is sociable, friendly, and gregarious would typically be described as an “Extravert.” Once we know she is an extravert, we can assume that she is sociable, friendly, and gregarious.

Statistical methods (specifically, a technique called factor analysis) helped to determine whether a small number of dimensions underlie the diversity of words that people like Allport and Odbert identified. The most widely accepted system to emerge from this approach was “The Big Five” or “Five-Factor Model” (Goldberg, 1990; McCrae & John, 1992; McCrae & Costa, 1987). The Big Five comprises five major traits shown in the figure below. A way to remember these five is with the acronym OCEAN (O is for Openness; C is for Conscientiousness; E is for Extraversion; A is for Agreeableness; N is for Neuroticism). Figure 11 provides descriptions of people who would score high and low on each of these traits.

Extraversion

Extraversion

Scores on the Big Five traits are mostly independent. That means that a person’s standing on one trait tells very little about their standing on the other traits of the Big Five. For example, a person can be extremely high in Extraversion and be either high or low on Neuroticism. Similarly, a person can be low in Agreeableness and be either high or low in Conscientiousness. Thus, in the Five-Factor Model, you need five scores to describe most of an individual’s personality.

Link to Learning

John Johnson has created a helpful website that has personality scales that can be used and taken by the general public: http://www.personal.psu.edu/j5j/IPIP/ipipneo120.htm

After seeing your scores, you can judge for yourself whether you think such tests are valid.

Other Traits Beyond the Five-Factor Model

Despite the popularity of the Five-Factor Model, it is certainly not the only model that exists. Some suggest that there are more than five major traits, or perhaps even fewer. For example, in one of the first comprehensive models to be proposed, Hans Eysenck suggested that Extraversion and Neuroticism are most important. Eysenck believed that by combining people’s standing on these two major traits, we could account for many of the differences in personality that we see in people (Eysenck, 1981). So for instance, a neurotic introvert would be shy and nervous, while a stable introvert might avoid social situations and prefer solitary activities, but he may do so with a calm, steady attitude and little anxiety or emotion. Interestingly, Eysenck attempted to link these two major dimensions to underlying differences in people’s biology. For instance, he suggested that introverts experienced too much sensory stimulation and arousal, which made them want to seek out quiet settings and less stimulating environments. More recently, Jeffrey Gray suggested that these two broad traits are related to fundamental reward and avoidance systems in the brain—extraverts might be motivated to seek reward and thus exhibit assertive, reward-seeking behavior, whereas people high in neuroticism might be motivated to avoid punishment and thus may experience anxiety as a result of their heightened awareness of the threats in the world around them (Gray, 1981. This model has since been updated; see Gray & McNaughton, 2000). These early theories have led to a burgeoning interest in identifying the physiological underpinnings of the individual differences that we observe.

Another revision of the Big Five is the HEXACO model of traits (Ashton & Lee, 2007). This model is similar to the Big Five, but it posits slightly different versions of some of the traits, and its proponents argue that one important class of individual differences was omitted from the Five-Factor Model. The HEXACO adds Honesty-Humility as a sixth dimension of personality. People high in this trait are sincere, fair, and modest, whereas those low in the trait are manipulative, narcissistic, and self-centered. Thus, trait theorists are agreed that personality traits are important in understanding behavior, but there are still debates on the exact number and composition of the traits that are most important.

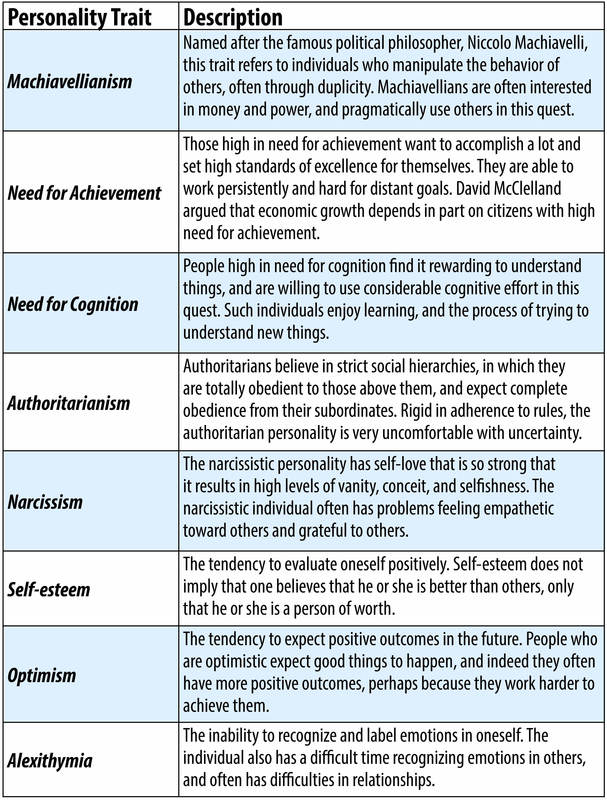

There are other important traits that are not included in comprehensive models like the Big Five. Although the five factors capture much that is important about personality, researchers have suggested other traits that capture interesting aspects of our behavior. In the figure below we present just a few, out of hundreds, of the other traits that have been studied by personality psychologists.

Not all of the above traits are currently popular with scientists, yet each of them has experienced popularity in the past. Although the Five-Factor Model has been the target of more rigorous research than some of the traits above, these additional personality characteristics give a good idea of the wide range of behaviors and attitudes that traits can cover.

The Person-Situation Debate

The ideas described here probably seem familiar, if not obvious to you. When asked to think about what our friends, enemies, family members, and colleagues are like, some of the first things that come to mind are their personality characteristics. We might think about how warm and helpful our first teacher was, how irresponsible and careless our brother is, or how demanding and insulting our first boss was. Each of these descriptors reflects a personality trait, and most of us generally think that the descriptions that we use for individuals accurately reflect their “characteristic pattern of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors,” or in other words, their personality.

But what if this idea were wrong? What if our belief in personality traits were an illusion and people are not consistent from one situation to the next? This was a possibility that shook the foundation of personality psychology in the late 1960s when Walter Mischel published a book called Personality and Assessment (1968). In this book, Mischel suggested that if one looks closely at people’s behavior across many different situations, the consistency is really not that impressive. In other words, children who cheat on tests at school may steadfastly follow all rules when playing games and may never tell a lie to their parents. In other words, he suggested, there may not be any general trait of honesty that links these seemingly related behaviors. Furthermore, Mischel suggested that observers may believe that broad personality traits like honesty exist, when in fact, this belief is an illusion. The debate that followed the publication of Mischel’s book was called the person-situation debate because it pitted the power of personality against the power of situational factors as determinants of the behavior that people exhibit.

Because of the findings that Mischel emphasized, many psychologists focused on an alternative to the trait perspective. Instead of studying broad, context-free descriptions, like the trait terms we’ve described so far, Mischel thought that psychologists should focus on people’s distinctive reactions to specific situations. For instance, although there may not be a broad and general trait of honesty, some children may be especially likely to cheat on a test when the risk of being caught is low and the rewards for cheating are high. Others might be motivated by the sense of risk involved in cheating and may do so even when the rewards are not very high. Thus, the behavior itself results from the child’s unique evaluation of the risks and rewards present at that moment, along with her evaluation of her abilities and values. Because of this, the same child might act very differently in different situations. Thus, Mischel thought that specific behaviors were driven by the interaction between very specific, psychologically meaningful features of the situation in which people found themselves, the person’s unique way of perceiving that situation, and his or her abilities for dealing with it. Mischel and others argued that it was these social-cognitive processes that underlie people’s reactions to specific situations that provide some consistency when situational features are the same. If so, then studying these broad traits might be more fruitful than cataloging and measuring narrow, context-free traits like Extraversion or Neuroticism.

In the years after the publication of Mischel’s (1968) book, debates raged about whether personality truly exists, and if so, how it should be studied. And, as is often the case, it turns out that a more moderate middle ground than what the situationists proposed could be reached. It is certainly true, as Mischel pointed out, that a person’s behavior in one specific situation is not a good guide to how that person will behave in a very different specific situation. Someone who is extremely talkative at one specific party may sometimes be reticent to speak up during class and may even act like a wallflower at a different party. But this does not mean that personality does not exist, nor does it mean that people’s behavior is completely determined by situational factors. Indeed, research conducted after the person-situation debate shows that on average, the effect of the “situation” is about as large as that of personality traits. However, it is also true that if psychologists assess a broad range of behaviors across many different situations, there are general tendencies that emerge. Personality traits give an indication about how people will act on average, but frequently they are not so good at predicting how a person will act in a specific situation at a certain moment in time. Thus, to best capture broad traits, one must assess aggregate behaviors, averaged over time and across many different types of situations. Most modern personality researchers agree that there is a place for broad personality traits and for the narrower units such as those studied by Walter Mischel.

Watch It

This is a student-made video that looks at characteristics of the OCEAN traits through a series of funny vignettes. It also presents on the Person vs Situation Debate. It was one of the winning entries in the 2016-17 Noba + Psi Chi Student Video Award.

Cultural Understandings of Personality

Learning Objectives

- Discuss personality differences of people from collectivist and individualist cultures and the varying approaches to studying personality (the cultural-comparative approach, the indigenous approach, and the combined approach)

The culture in which you live is one of the most important environmental factors that shapes your personality (Triandis & Suh, 2002). The term culture refers to all of the beliefs, customs, art, and traditions of a particular society. Culture is transmitted to people through language as well as through the modeling of culturally acceptable and nonacceptable behaviors that are either rewarded or punished (Triandis & Suh, 2002). With these ideas in mind, personality psychologists have become interested in the role of culture in understanding personality. They ask whether personality traits are the same across cultures or if there are variations. It appears that there are both universal and culture-specific aspects that account for variation in people’s personalities.

Why might it be important to consider cultural influences on personality? Western ideas about personality may not apply to other cultures (Benet-Martinez & Oishi, 2008). There is evidence that the strength of personality traits varies across cultures. Let’s take a look at some of the Big Five factors (conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness, and extroversion) across cultures. As you will learn when you study social psychology, Asian cultures are more collectivist, and people in these cultures tend to be less extroverted. People in Central and South American cultures tend to score higher on openness to experience, whereas Europeans score higher on neuroticism (Benet-Martinez & Karakitapoglu-Aygun, 2003).

According to a study by Rentfrow and colleagues, there also seem to be regional personality differences within the United States (Figure 15). Researchers analyzed responses from over 1.5 million individuals in the United States and found that there are three distinct regional personality clusters: Cluster 1, which is in the Upper Midwest and Deep South, is dominated by people who fall into the “friendly and conventional” personality; Cluster 2, which includes the West, is dominated by people who are more relaxed, emotionally stable, calm, and creative; and Cluster 3, which includes the Northeast, has more people who are stressed, irritable, and depressed. People who live in Clusters 2 and 3 are also generally more open (Rentfrow et al., 2013).

One explanation for the regional differences is selective migration (Rentfrow et al., 2013). Selective migration is the concept that people choose to move to places that are compatible with their personalities and needs. For example, a person high on the agreeable scale would likely want to live near family and friends and would choose to settle or remain in such an area. In contrast, someone high on openness would prefer to settle in a place that is recognized as diverse and innovative (such as California). Further, Rentfrow et al. (2009) noted an overlap between geographical regions and personality characteristics that goes beyond the often-used explanations of religion, racial diversity, and education. Their research suggests that the psychological profile of a region is closely related to that of its residents. They found that levels of openness and conscientiousness in a state may predict voting patterns, indicating that there are correlations between geographic regions and personality differences between liberals and conservatives relating to political views, levels of economic vitality, and entrepreneurial rates.

Personality in Individualist and Collectivist Cultures

Individualist cultures and collectivist cultures emphasize different basic values. People who live in individualist cultures tend to believe that independence, competition, and personal achievement are important. Individuals in Western nations such as the United States, England, and Australia score high on individualism (Oyserman et al., 2002). People who live in collectivist cultures value social harmony, respectfulness, and group needs over individual needs. Individuals who live in countries in Asia, Africa, and South America score high on collectivism (Hofstede, 2001; Triandis, 1995). These values influence personality. For example, Yang (2006) found that people in individualist cultures displayed more personally oriented personality traits, whereas people in collectivist cultures displayed more socially oriented personality traits. Frewer and Bleus (1991) conducted a study of the Eysenck Personality Inventory in a collectivist culture using Papua New Guinean university students. They found that the results of the personality inventory were only relevant when analyzed within the context of a collectivist society. Similarly, Dana (1986) suggested that personality assessment services for Native Americans are often provided without proper recognition of culture-specific responses and a tribe-specific frame of reference. Assessors need to have more than general knowledge of history, tribal differences, contemporary culture on reservations, and levels of acculturation in order to interpret psychological test responses with minimal bias.

Approaches to Studying Personality in a Cultural Context

Three approaches can be used to study personality in a cultural context, the cultural-comparative approach; the indigenous approach; and the combined approach, which incorporates elements of both views. Since ideas about personality have a Western basis, the cultural-comparative approach seeks to test Western ideas about personality in other cultures to determine whether they can be generalized and if they have cultural validity (Cheung et al., 2011). For example, recall from the previous section on the trait perspective that researchers used the cultural-comparative approach to test the universality of McCrae and Costa’s Five-Factor Model. They found applicability in numerous cultures around the world, with the Big Five factors being stable in many cultures (McCrae & Costa, 1997; McCrae et al., 2005). The indigenous approach came about in reaction to the dominance of Western approaches to the study of personality in non-Western settings (Cheung et al., 2011). Because Western-based personality assessments cannot fully capture the personality constructs of other cultures, the indigenous model has led to the development of personality assessment instruments that are based on constructs relevant to the culture being studied (Cheung et al., 2011). The third approach to cross-cultural studies of personality is the combined approach, which serves as a bridge between Western and indigenous psychology as a way of understanding both universal and cultural variations in personality (Cheung et al., 2011).

Think It Over

- According to the work of Rentfrow and colleagues, personalities are not randomly distributed. Instead, they fit into distinct geographic clusters. Based on where you live, do you agree or disagree with the traits associated with yourself and the residents of your area of the country? Why or why not?

Personality Assessment

Learning Objectives

- Appreciate the diversity of methods that are used to measure personality characteristics.

- Understand the logic, strengths and weaknesses of each approach.

- Gain a better sense of the overall validity and range of applications of personality tests.

Objective Tests

Objective tests (Loevinger, 1957; Meyer & Kurtz, 2006) represent the most familiar and widely used approach to assessing personality. Objective tests involve administering a standard set of items, each of which is answered using a limited set of response options (e.g., true or false; strongly disagree, slightly disagree, slightly agree, strongly agree). Responses to these items then are scored in a standardized, predetermined way. For example, self-ratings on items assessing talkativeness, assertiveness, sociability, adventurousness, and energy can be summed up to create an overall score on the personality trait of extraversion.

It must be emphasized that the term “objective” refers to the method that is used to score a person’s responses, rather than to the responses themselves. As noted by Meyer and Kurtz (2006, p. 233), “What is objective about such a procedure is that the psychologist administering the test does not need to rely on judgment to classify or interpret the test-taker’s response; the intended response is clearly indicated and scored according to a pre-existing key.” In fact, as we will see, a person’s test responses may be highly subjective and can be influenced by a number of different rating biases.

Basic Types of Objective Tests

Self-report measures

Objective personality tests can be further subdivided into two basic types. The first type—which easily is the most widely used in modern personality research—asks people to describe themselves. This approach offers two key advantages. First, self-raters have access to an unparalleled wealth of information: After all, who knows more about you than you yourself? In particular, self-raters have direct access to their own thoughts, feelings, and motives, which may not be readily available to others (Oh et al., 2011; Watson et al., 2000). Second, asking people to describe themselves is the simplest, easiest, and most cost-effective approach to assessing personality. Countless studies, for instance, have involved administering self-report measures to college students, who are provided some relatively simple incentive (e.g., extra course credit) to participate.

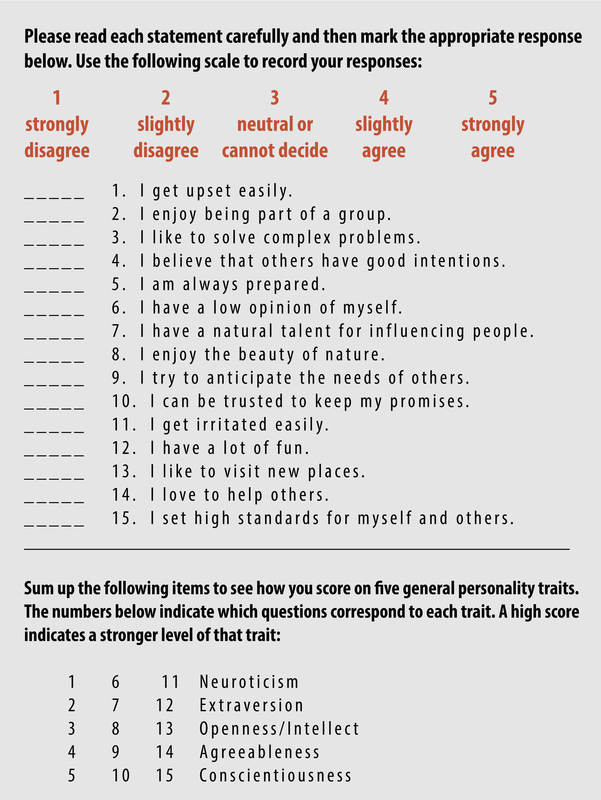

The items included in self-report measures may consist of single words (e.g., assertive), short phrases (e.g., am full of energy), or complete sentences (e.g., I like to spend time with others). Below is a sample self-report measure assessing the general traits comprising the five-factor model of personality (John & Srivastava, 1999; McCrae et al., 2005). The sentences shown below are modified versions of items included in the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) (Goldberg et al., 2006), which is a rich source of personality-related content in the public domain (for more information about IPIP, go to: http://ipip.ori.org/).

Self-report personality tests show impressive validity in relation to a wide range of important outcomes. For example, self-ratings of conscientiousness are significant predictors of both overall academic performance (e.g., cumulative grade point average; Poropat, 2009) and job performance (Oh et al., 2011). Roberts et al. (2007) reported that self-rated personality predicted occupational attainment, divorce, and mortality. Similarly, Friedman et al. (2010) showed that personality ratings collected early in life were related to happiness/well-being, physical health, and mortality risk assessed several decades later. Finally, self-reported personality has important and pervasive links to psychopathology. Most notably, self-ratings of neuroticism are associated with a wide array of clinical syndromes, including anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, substance use disorders, somatoform disorders, eating disorders, personality and conduct disorders, and schizophrenia/schizotypy (Kotov et al., 2010; Mineka et al., 1998).

At the same time, however, it is clear that this method is limited in a number of ways. First, raters may be motivated to present themselves in an overly favorable, socially desirable way (Paunonen & LeBel, 2012). This is a particular concern in “high-stakes testing,” that is, situations in which test scores are used to make important decisions about individuals (e.g., when applying for a job). Second, personality ratings reflect a self-enhancement bias (Vazire & Carlson, 2011); in other words, people are motivated to ignore (or at least downplay) some of their less desirable characteristics and to focus instead on their more positive attributes. Third, self-ratings are subject to the reference group effect (Heine et al., 2008); that is, we base our self-perceptions, in part, on how we compare to others in our sociocultural reference group. For instance, if you tend to work harder than most of your friends, you will see yourself as someone who is relatively conscientious, even if you are not particularly conscientious in any absolute sense.

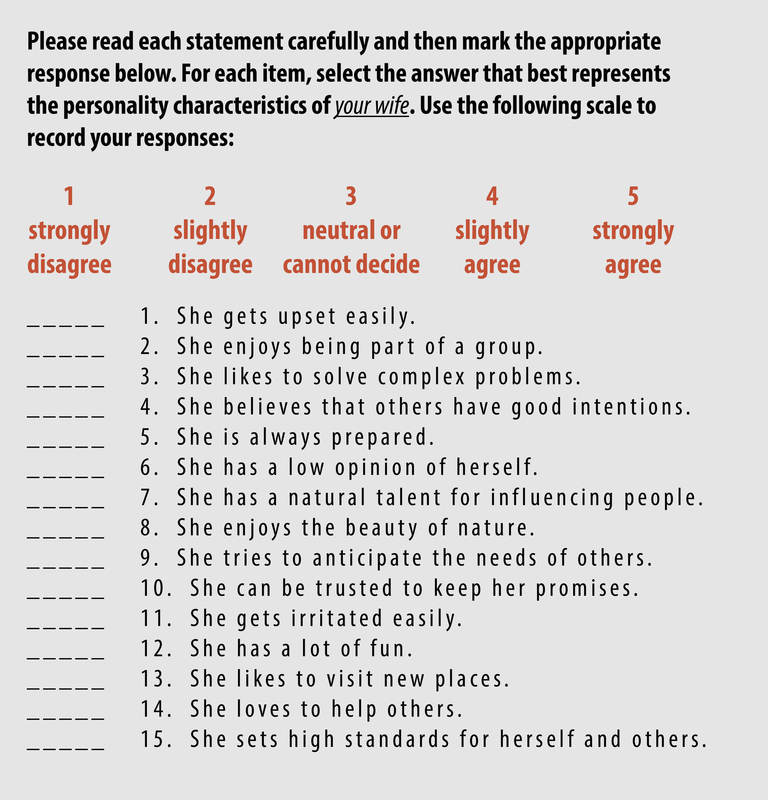

Informant ratings

Another approach is to ask someone who knows a person well to describe his or her personality characteristics. In the case of children or adolescents, the informant is most likely to be a parent or teacher. In studies of older participants, informants may be friends, roommates, dating partners, spouses, children, or bosses (Oh et al., 2011; Vazire & Carlson, 2011; Watson et al., 2000).

Generally speaking, informant ratings are similar in format to self-ratings. As was the case with self-report, items may consist of single words, short phrases, or complete sentences. Indeed, many popular instruments include parallel self- and informant-rating versions, and it often is relatively easy to convert a self-report measure so that it can be used to obtain informant ratings. Table 2 illustrates how the self-report instrument shown in Table 1 can be converted to obtain spouse-ratings (in this case, having a husband describe the personality characteristics of his wife).

Informant ratings are particularly valuable when self-ratings are impossible to collect (e.g., when studying young children or cognitively impaired adults) or when their validity is suspect (e.g., as noted earlier, people may not be entirely honest in high-stakes testing situations). They also may be combined with self-ratings of the same characteristics to produce more reliable and valid measures of these attributes (McCrae, 1994).

Informant ratings offer several advantages in comparison to other approaches to assessing personality. A well-acquainted informant presumably has had the opportunity to observe large samples of behavior in the person he or she is rating. Moreover, these judgments presumably are not subject to the types of defensiveness that potentially can distort self-ratings (Vazire & Carlson, 2011). Indeed, informants typically have strong incentives for being accurate in their judgments. As Funder and Dobroth (1987, p. 409), put it, “Evaluations of the people in our social environment are central to our decisions about who to befriend and avoid, trust and distrust, hire and fire, and so on.”

Informant personality ratings have demonstrated a level of validity in relation to important life outcomes that is comparable to that discussed earlier for self-ratings. Indeed, they outperform self-ratings in certain circumstances, particularly when the assessed traits are highly evaluative in nature (e.g., intelligence, charm, creativity; see Vazire & Carlson, 2011). For example, Oh et al. (2011) found that informant ratings were more strongly related to job performance than were self-ratings. Similarly, Oltmanns and Turkheimer (2009) summarized evidence indicating that informant ratings of Air Force cadets predicted early, involuntary discharge from the military better than self-ratings.

Nevertheless, informant ratings also are subject to certain problems and limitations. One general issue is the level of relevant information that is available to the rater (Funder, 2012). For instance, even under the best of circumstances, informants lack full access to the thoughts, feelings, and motives of the person they are rating. This problem is magnified when the informant does not know the person particularly well and/or only sees him or her in a limited range of situations (Funder, 2012; Beer & Watson, 2010).

Informant ratings also are subject to some of the same response biases noted earlier for self-ratings. For instance, they are not immune to the reference group effect. Indeed, it is well-established that parent ratings often are subject to a sibling contrast effect, such that parents exaggerate the true magnitude of differences between their children (Pinto et al., 2012). Furthermore, in many studies, individuals are allowed to nominate (or even recruit) the informants who will rate them. Because of this, it most often is the case that informants (who, as noted earlier, may be friends, relatives, or romantic partners) like the people they are rating. This, in turn, means that informants may produce overly favorable personality ratings. Indeed, their ratings actually can be more favorable than the corresponding self-ratings (Watson & Humrichouse, 2006). This tendency for informants to produce unrealistically positive ratings has been termed the letter of recommendation effect (Leising et al., 2010) and the honeymoon effect when applied to newlyweds (Watson & Humrichouse, 2006).

Other Ways of Classifying Objective Tests

Comprehensiveness

In addition to the source of the scores, there are at least two other important dimensions on which personality tests differ. The first such dimension concerns the extent to which an instrument seeks to assess personality in a reasonably comprehensive manner. At one extreme, many widely used measures are designed to assess a single core attribute. Examples of these types of measures include the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (Bagby et al., 1994), the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965), and the Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire (Gamez et al., 2011). At the other extreme, a number of omnibus inventories contain a large number of specific scales and purport to measure personality in a reasonably comprehensive manner. These instruments include the California Psychological Inventory (Gough, 1987), the Revised HEXACO Personality Inventory (HEXACO-PI-R) (Lee & Ashton, 2006), the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (Patrick et al., 2002), the NEO Personality Inventory-3 (NEO-PI-3) (McCrae et al., 2005), the Personality Research Form (Jackson, 1984), and the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (Cattell et al., 1980).

Breadth of the target characteristics

Second, personality characteristics can be classified at different levels of breadth or generality. For example, many models emphasize broad, “big” traits such as neuroticism and extraversion. These general dimensions can be divided up into several distinct yet empirically correlated component traits. For example, the broad dimension of extraversion contains such specific component traits as dominance (extraverts are assertive, persuasive, and exhibitionistic), sociability (extraverts seek out and enjoy the company of others), positive emotionality (extraverts are active, energetic, cheerful, and enthusiastic), and adventurousness (extraverts enjoy intense, exciting experiences).

Some popular personality instruments are designed to assess only the broad, general traits. For example, similar to the sample instrument displayed previously, the Big Five Inventory (John & Srivastava, 1999) contains brief scales assessing the broad traits of neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. In contrast, many instruments—including several of the omnibus inventories mentioned earlier—were designed primarily to assess a large number of more specific characteristics. Finally, some inventories—including the HEXACO-PI-R and the NEO-PI-3—were explicitly designed to provide coverage of both general and specific trait characteristics. For instance, the NEO-PI-3 contains six specific facet scales (e.g., Gregariousness, Assertiveness, Positive Emotions, Excitement Seeking) that then can be combined to assess the broad trait of extraversion.

Watch It

Watch this CrashCourse video to better understand how personality is measured:

Behavioral and Performance Measures

A final approach is to infer important personality characteristics from direct samples of behavior. For example, Funder and Colvin (1988) brought opposite-sex pairs of participants into the laboratory and had them engage in a five-minute “getting acquainted” conversation; raters watched videotapes of these interactions and then scored the participants on various personality characteristics. Mehl et al. (2006) used the electronically activated recorder (EAR) to obtain samples of ambient sounds in participants’ natural environments over a period of two days; EAR-based scores then were related to self- and observer-rated measures of personality. For instance, more frequent talking over this two-day period was significantly related to both self- and observer-ratings of extraversion. As a final example, Gosling et al. (2002) sent observers into college students’ bedrooms and then had them rate the students’ personality characteristics on the Big Five traits. The averaged observer ratings correlated significantly with participants’ self-ratings on all five traits. Follow-up analyses indicated that conscientious students had neater rooms, whereas those who were high in openness to experience had a wider variety of books and magazines.

Behavioral measures offer several advantages over other approaches to assessing personality. First, because behavior is sampled directly, this approach is not subject to the types of response biases (e.g., self-enhancement bias, reference group effect) that can distort scores on objective tests. Second, as is illustrated by the Mehl et al. (2006) and Gosling et al. (2002) studies, this approach allows people to be studied in their daily lives and in their natural environments, thereby avoiding the artificiality of other methods (Mehl et al., 2006). Finally, this is the only approach that actually assesses what people do, as opposed to what they think or feel (see Baumeister et al., 2007).

At the same time, however, this approach also has some disadvantages. This assessment strategy clearly is much more cumbersome and labor intensive than using objective tests, particularly self-report. Moreover, similar to projective tests, behavioral measures generate a rich set of data that then need to be scored in a reliable and valid way. Finally, even the most ambitious study only obtains relatively small samples of behavior that may provide a somewhat distorted view of a person’s true characteristics. For example, your behavior during a “getting acquainted” conversation on a single given day inevitably will reflect a number of transient influences (e.g., level of stress, quality of sleep the previous night) that are idiosyncratic to that day.

No single method of assessing personality is perfect or infallible; each of the major methods has both strengths and limitations. By using a diversity of approaches, researchers can overcome the limitations of any single method and develop a more complete and integrative view of personality.

Think it Over

Why might a prospective employer screen applicants using personality assessments?

Chapter References (Click to expand)

Adler, A. (1930). Individual psychology. In C. Murchison (Ed.), Psychologies of 1930 (pp. 395–405). Clark University Press.

Adler, A. (1937). A school girl’s exaggeration of her own importance. International Journal of Individual Psychology, 3(1), 3–12.

Adler, A. (1956). The individual psychology of Alfred Adler: A systematic presentation in selections from his writings. (C. H. Ansbacher & R. Ansbacher, Eds.). Harper.

Adler, A. (1961). The practice and theory of individual psychology. In T. Shipley (Ed.), Classics in psychology (pp. 687–714). Philosophical Library

Adler, A. (1964). Superiority and social interest. Norton.

Akomolafe, M. J. (2013). Personality characteristics as predictors of academic performance of secondary school students. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4(2), 657–664.

Allport, G. W., & Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait names: A psycholexical study. Psychological Monographs, 47, 211.

Aronow, E., Weiss, K. A., & Rezinkoff, M. (2001). A practical guide to the Thematic Apperception Test. Brunner Routledge.

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2007). Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality and Social Psychological Review, 11, 150–166.

Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2009). Predicting actual behavior from the explicit and implicit self-concept of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 533–548.

Bagby, R. M., Parker, J. D. A., Taylor, G. J. (1994). The Twenty-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38, 23–32.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1995). Self-efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge University Press.

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Funder, D. C. (2007). Psychology as the science of self-reports and finger movements: Whatever happened to actual behavior? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2, 396–403.

Beer, A., & Watson, D. (2010). The effects of information and exposure on self-other agreement. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 38–45.

Benassi, V. A., Sweeney, P. D., & Dufour, C. L. (1988). Is there a relation between locus of control orientation and depression? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97(3), 357.

Ben-Porath, Y., & Tellegen, A. (2008). Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-RF. University of Minnesota Press.

Benet-Martínez, V. & Karakitapoglu-Aygun, Z. (2003). The interplay of cultural values and personality in predicting life-satisfaction: Comparing Asian- and European-Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34, 38–61.

Benet-Martínez, V., & Oishi, S. (2008). Culture and personality. In O. P. John, R.W. Robins, L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research. Guildford Press.

Beutler, L. E., Nussbaum, P. D., & Meredith, K. E. (1988). Changing personality patterns of police officers. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 19(5), 503–507.

Bouchard, T., Jr. (1994). Genes, environment, and personality. Science, 264, 1700–1701.

Bouchard, T., Jr., Lykken, D. T., McGue, M., Segal, N. L., & Tellegen, A. (1990). Sources of human psychological differences: The Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart. Science, 250, 223–228.

Burger, J. (2008). Personality (7th ed.). Thompson Higher Education.

Carter, J. E., and Heath, B. H. (1990). Somatotyping: Development and applications. Cambridge University Press.

Carter, S., Champagne, F., Coates, S., Nercessian, E., Pfaff, D., Schecter, D., & Stern, N. B. (2008). Development of temperament symposium. Philoctetes Center, New York.

Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Reviews of Psychology, 56, 453–484.

Cattell, R. B. (1946). The description and measurement of personality. Harcourt, Brace, & World.

Cattell, R. B. (1957). Personality and motivation structure and measurement. World Book.

Cattell, R. B., Eber, H. W, & Tatsuoka, M. M. (1980). Handbook for the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF). Champaign, IL: Institute for Personality and Ability Testing.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2008). Personality, intelligence, and approaches to learning as predictors of academic performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 1596–1603.

Cheung, F. M., van de Vijver, F. J. R., & Leong, F. T. L. (2011). Toward a new approach to the study of personality in culture. American Psychologist, 66(7), 593–603.

Clark, A. L., & Watson, D. (2008). Temperament: An organizing paradigm for trait psychology. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Previn (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 265–286). Guilford Press.

Conrad, N. & Party, M.W. (2012). Conscientiousness and academic performance: A Mediational Analysis. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 6 (1), 1–14.

Cortés, J., & Gatti, F. (1972). Delinquency and crime: A biopsychological approach. Seminar Press.

Costantino, G. (1982). TEMAS: A new technique for personality research assessment of Hispanic children. Hispanic Research Center, Fordham University Research Bulletin, 5, 3–7.

Cramer, P. (2004). Storytelling, narrative, and the Thematic Apperception Test. Guilford Press.

Damon, S. (1955). Physique and success in military flying. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 13(2), 217–252.

Donnellan, M. B., & Lucas, R. E. (2008). Age differences in the big five across the life span: Evidence from two national samples. Psychology and Aging, 23(3), 558–566.

Donnellan, M. B., Oswald, F. L., Baird, B. M., & Lucas, R. E. (2006). The mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychological Assessment, 18, 192–203.

Duzant, R. (2005). Differences of emotional tone and story length of African American respondents when administered the Contemporized Themes Concerning Blacks test versus the Thematic Apperception Test. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Chicago, IL.

Exner, J. E. (2002). The Rorschach: Basic foundations and principles of interpretation (Vol. 1). Wiley.

Exner, J. E. (2003). The Rorschach: A comprehensive system (4th ed.). Wiley.

Eysenck, H. J. (1970). The structure of human personality. Methuen.

Eysenck, H. J. (1981). A model for personality. Springer Verlag.

Eysenck, H. J. (1990). An improvement on personality inventory. Current Contents: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 22(18), 20.

Eysenck, H. J. (1992). Four ways five factors are not basic. Personality and Individual Differences, 13, 667–673.

Eysenck, H. J. (2009). The biological basis of personality (3rd ed.). Transaction Publishers.

Eysenck, S. B. G., & Eysenck, H. J. (1963). The validity of questionnaire and rating assessments of extroversion and neuroticism, and their factorial stability. British Journal of Psychology, 54, 51–62.

Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, M. W. (1985). Personality and individual differences: A natural science approach. Plenum Press.

Eysenck, S. B. G., Eysenck, H. J., & Barrett, P. (1985). A revised version of the psychoticism scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 6(1), 21–29.

Fazeli, S. H. (2012). The exploring nature of the assessment instrument of five factors of personality traits in the current studies of personality. Asian Social Science, 8(2), 264–275.

Fancher, R. W. (1979). Pioneers of psychology. Norton.

Frank, L. K. (1939). Projective methods for the study of personality. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 8, 389–413.

Freud, S. (1920). Resistance and suppression. A general introduction to psychoanalysis (pp. 248–261). Horace Liveright.

Freud, S. (1923/1949). The ego and the id. Hogarth.

Freud, S. (1931/1968). Female sexuality. In J. Strachey (Ed. &Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 21). Hogarth Press.

Friedman, H. S., Kern, K. L., & Reynolds, C. A. (2010). Personality and health, subjective well-being, and longevity. Journal of Personality, 78, 179–215.

Funder, D. C. (2001). Personality. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 197–221.

Funder, D. C. (2012). Accurate personality judgment. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21, 177–182.

Funder, D. C., & Colvin, C. R. (1988). Friends and strangers: Acquaintanceship, agreement, and the accuracy of personality judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 149–158.

Funder, D. C., & Dobroth, K. M. (1987). Differences between traits: Properties associated with interjudge agreement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 409–418.

Gamez, W., Chmielewski, M., Kotov, R., Ruggero, C., & Watson, D. (2011). Development of a measure of experiential avoidance: The Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 23, 692–713.

Genovese, J. E. C. (2008). Physique correlates with reproductive success in an archival sample of delinquent youth. Evolutionary Psychology, 6(3), 369-385.

Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative description of personality: The Big Five personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1216–1229.

Goldberg, L. R., Johnson, J. A., Eber, H. W., Hogan, R., Ashton, M. C., Cloninger, C. R., & Gough, H. C. (2006). The International Personality Item Pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 84–96.

Gosling, S. D., Ko, S. J., Mannarelli, T., & Morris, M. E. (2002). A room with a cue: Personality judgments based on offices and bedrooms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 379–388.

Gough, H. G. (1987). California Psychological Inventory [Administrator’s guide]. Consulting Psychologists Press.

Gray, J. A. (1981). A critique of Eysenck’s theory of personality. In H. J. Eysenck (Ed.), A Model for Personality (pp. 246-276). New York: Springer Verlag.

Gray, J. A. & McNaughton, N. (2000). The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system (second edition).Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heine, S. J., Buchtel, E. E., & Norenzayan, A. (2008). What do cross-national comparisons of personality traits tell us? The case of conscientiousness. Psychological Science, 19, 309–313.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Sage.

Holaday, D., Smith, D. A., & Sherry, Alissa. (2010). Sentence completion tests: A review of the literature and results of a survey of members of the society for personality assessment. Journal of Personality Assessment, 74(3), 371–383.

Hoy, M. (1997). Contemporizing of the Themes Concerning Blacks test (C-TCB). California School of Professional Psychology.

Hoy-Watkins, M., & Jenkins-Moore, V. (2008). The Contemporized-Themes Concerning Blacks Test (C-TCB). In S. R. Jenkins (Ed.), A Handbook of Clinical Scoring Systems for Thematic Apperceptive Techniques (pp. 659–698). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hothersall, D. (1995). History of psychology. McGraw-Hill.

Jackson, D. N. (1984). Personality Research Form manual (3rd ed.). Research Psychologists Press.

Jang, K. L., Livesley, W. J., & Vernon, P. A. (1996). Heritability of the big five personality dimensions and their facts: A twin study. Journal of Personality, 64(3), 577–591.

Jang, K. L., Livesley, W. J., Ando, J., Yamagata, S., Suzuki, A., Angleitner, A., et al. (2006). Behavioral genetics of the higher-order factors of the Big Five. Personality and Individual Differences, 41, 261–272.

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). The Guilford Press.

Judge, T. A., Livingston, B. A., & Hurst, C. (2012). Do nice guys-and gals- really finish last? The joint effects of sex and agreeableness on income. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(2), 390–407.

Jung, C. G. (1923). Psychological types. Harcourt Brace.

Jung, C. G. (1928). Contributions to analytical psychology. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and his symbols. Doubleday and Company.

Jung, C., & Kerenyi, C. (1963). Science of mythology. In R. F. C. Hull (Ed. & Trans.), Essays on the myth of the divine child and the mysteries of Eleusis. Harper & Row.

Kotov, R., Gamez, W., Schmidt, F., & Watson, D. (2010). Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 768–821.

Launer, J. (2005). Anna O. and the ‘talking cure.’ QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 98(6), 465–466.

Lecci, L. B. & Magnavita, J. J. (2013). Personality theories: A scientific approach. Bridgepoint Education.

Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2006). Further assessment of the HEXACO Personality Inventory: Two new facet scales and an observer report form. Psychological Assessment, 18, 182–191.

Lefcourt, H. M. (1982). Locus of control: Current trends in theory and research (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

Leising, D., Erbs, J., & Fritz, U. (2010). The letter of recommendation effect in informant ratings of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 668–682.

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 140, 1–55.

Lilienfeld, S. O., Wood, J. M., & Garb, H. N. (2000). The scientific status of projective techniques. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 1(2), 27–66.

Loevinger, J. (1957). Objective tests as instruments of psychological theory. Psychological Reports, 3, 635–694.

Maltby, J., Day, L., & Macaskill, A. (2007). Personality, individual differences and intelligence (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality. Harper & Row.

Maslow, A. H. (1950). Self-actualizing people: A study of psychological health. In W. Wolff (Ed.), Personality Symposia: Symposium 1 on Values (pp. 11–34). New York: Grune & Stratton.

Matthews, G., Deary, I. J., & Whiteman, M. C. (2003). Personality traits. Cambridge University Press.

McClelland, D. C., Koestner, R., & Weinberger, J. (1989). How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ? Psychological Review, 96, 690–702.

McCrae, R. R. (1994). The counterpoint of personality assessment: Self-reports and observer ratings. Assessment, 1, 159–172.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 81–90.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist, 52(5), 509–516.

McCrae, R. R., et al. (2005). Universal features of personality traits from the observer’s perspective: Data from 50 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 547–561.

McCrae, R. R., Costa, P. T., Jr., & Martin, T. A. (2005). The NEO-PI-3: A more readable Revised NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 84, 261–270.

McCrae, R. R. & John, O. P. (1992). An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 60, 175–215.

McGregor, I., McAdams, D. P., & Little, B. R. (2006). Personal projects, life stories, and happiness: On being true to traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 551–572.

Mehl, M. R., Gosling, S. D., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2006). Personality in its natural habitat: Manifestations and implicit folk theories of personality in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 862–877.

Meyer, G. J., & Kurtz, J. E. (2006). Advancing personality assessment terminology: Time to retire “objective” and “projective” as personality test descriptors. Journal of Personality Assessment, 87, 223–225.

Mihura, J. L., Meyer, G. J., Dumitrascu, N., & Bombel, G. (2012). The validity of individual Rorschach variables: Systematic Reviews and meta-analyses of the Comprehensive System. Psychological Bulletin. (Advance online publication.) doi:10.1037/a0029406

Mineka, S., Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1998). Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 377–412.

Mischel, W. (1968). Personality and assessment. John Wiley.

Mischel, W. (1993). Introduction to personality (5th ed.). Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.