Chapter 12: Polyrhythms—two against three and three against two

About This Chapter

About This Chapter: In this chapter, we will explore polyrhythms for the first time. We’ll focus specifically on the two-against-three and three-against-two polyrhythms.

Polyrhythm describes music that features different rhythmic divisions that aren’t related to one another occurring simultaneously. In the example below, we see several polyrhythms: the triplets against the eighth notes in measure 1 (we’ll call this three against two), the sixteenth notes against the triplets in measure 2 (four against three), and the quintuplets (which we’ll study in more depth in Chapter 21) against the eighth notes in measure 3 (five against two). In measure 4, we see two different rhythmic divisions against each other (sixteenth notes against eighth notes), but we don’t consider this a polyrhythm because the two divisions are related to one another—sixteenth notes are just a subdivision of eighth notes. Another way to think about it is that since the sixteenth notes and eighth notes align more often than just on the beat (they both attack on the “&” of the beat), they are not considered a polyrhythm.

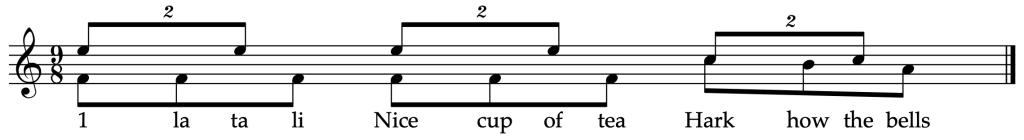

In this chapter, we’ll focus on two-against-three and three-against-two polyrhythms. In measure 1 of the example below, the division of the beat into three equal parts (“1 la li”) is the normal division. When we put a division into two equal parts (“1 &”) against it, we create a two-against-three polyrhythm. In measure 2, the opposite happens: the normal division of the beat is into two equal parts (“1 &”), but we put a division into three equal parts against it (“1 la li”) to create a three-against-two polyrhythm.

So what do these rhythms sound like together? One helpful way to conceptualize it is to think about the “composite rhythm,” or the combined rhythm of both parts. If you combine the attacks from each part of a two-against-three or three-against-two polyrhythm into a single line, it would sound like the rhythm in the figure below: “1 la ta li.” This is a rhythm we’ve already seen many times! Now all we need to do is figure out how to separate that rhythm into two parts.

For some people, it’s helpful to keep that composite rhythm in mind when performing these polyrhythms. You may find it helpful to think the syllables “1 la ta li” as you’re performing the two-against-three or three-against-two polyrhythms. Or you may find it helpful to associate a phrase with the composite rhythm. In the second beat of the two examples below, you can see the phrase “nice cup of tea” fitted onto the polyrhythm. In beat three of the two examples, the first line of “Carol of the Bells”—“hark how the bells”—has been put onto the rhythms, along with the appropriate pitches. The “Carol of the Bells” rhythm is precisely the composite rhythm of this polyrhythm!

It may help you to conceptualize the three-against-two/two-against-three polyrhythm by seeing a visual representation. The grid below represents a single beat that has been divided into six equal parts. The grey boxes in the top line represent three evenly spaced attacks, while the grey boxes in the bottom line represent two evenly spaced attacks. Notice how the attacks in the third, fourth, and fifth columns happen right in a row.

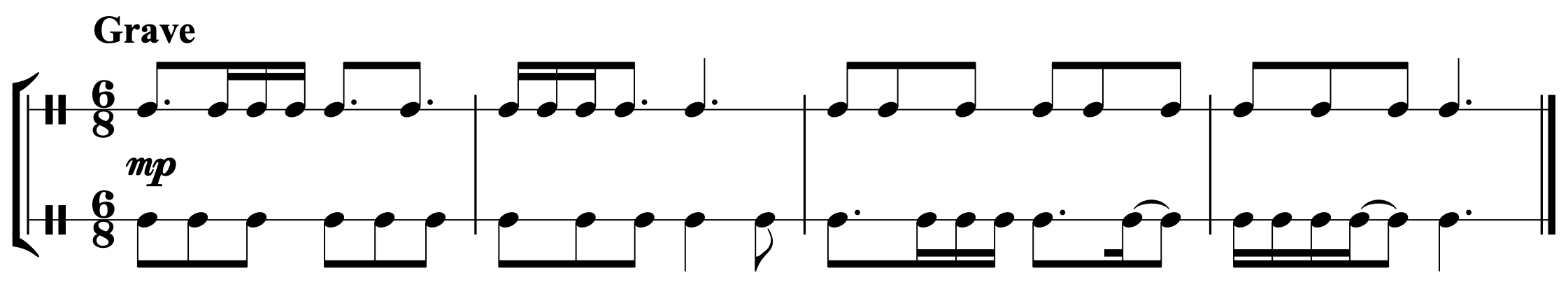

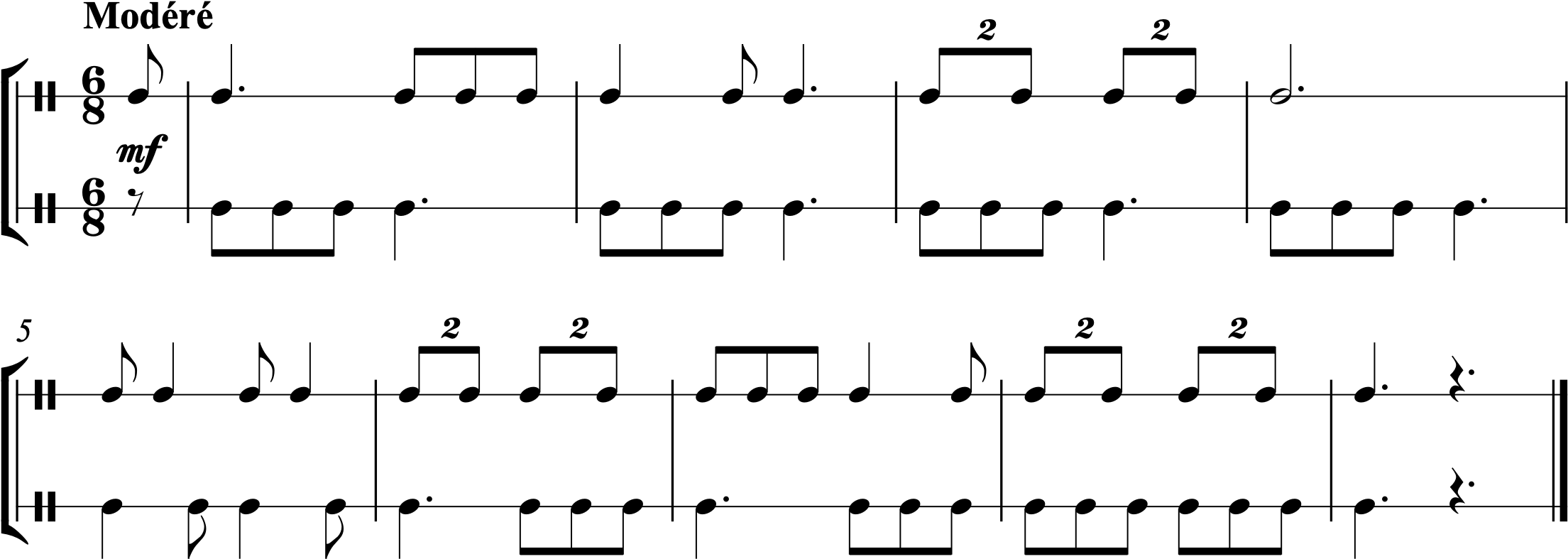

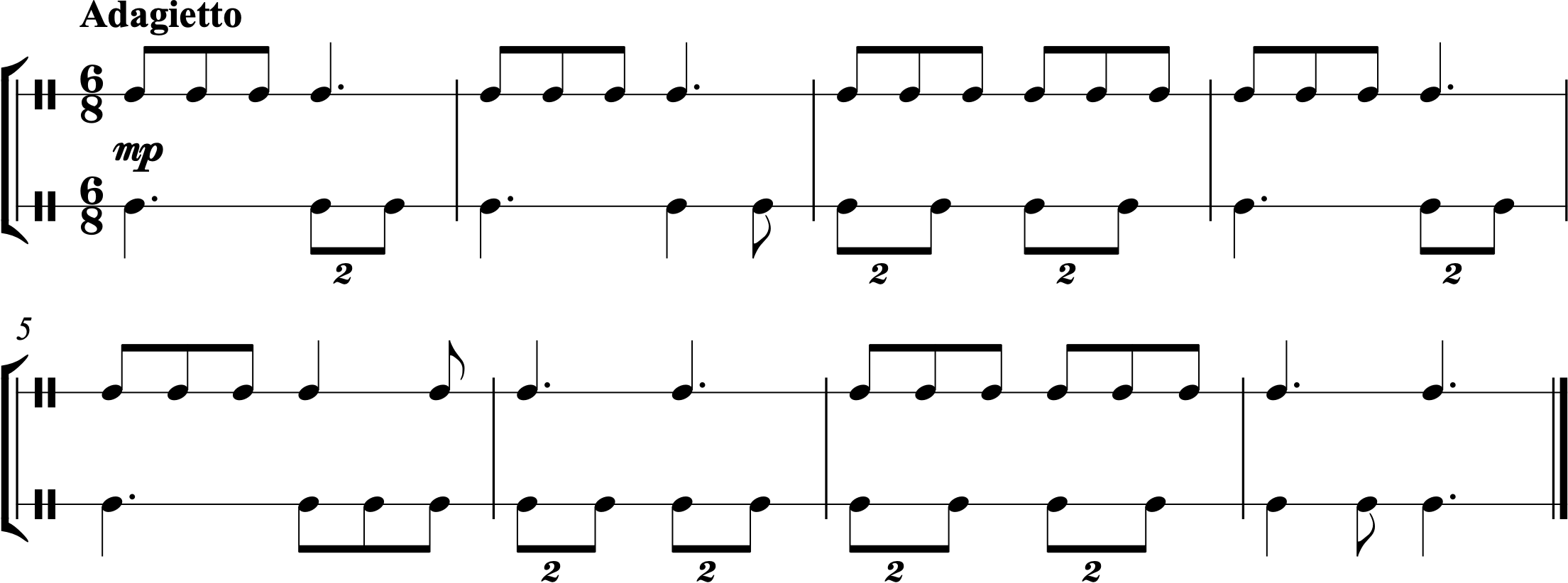

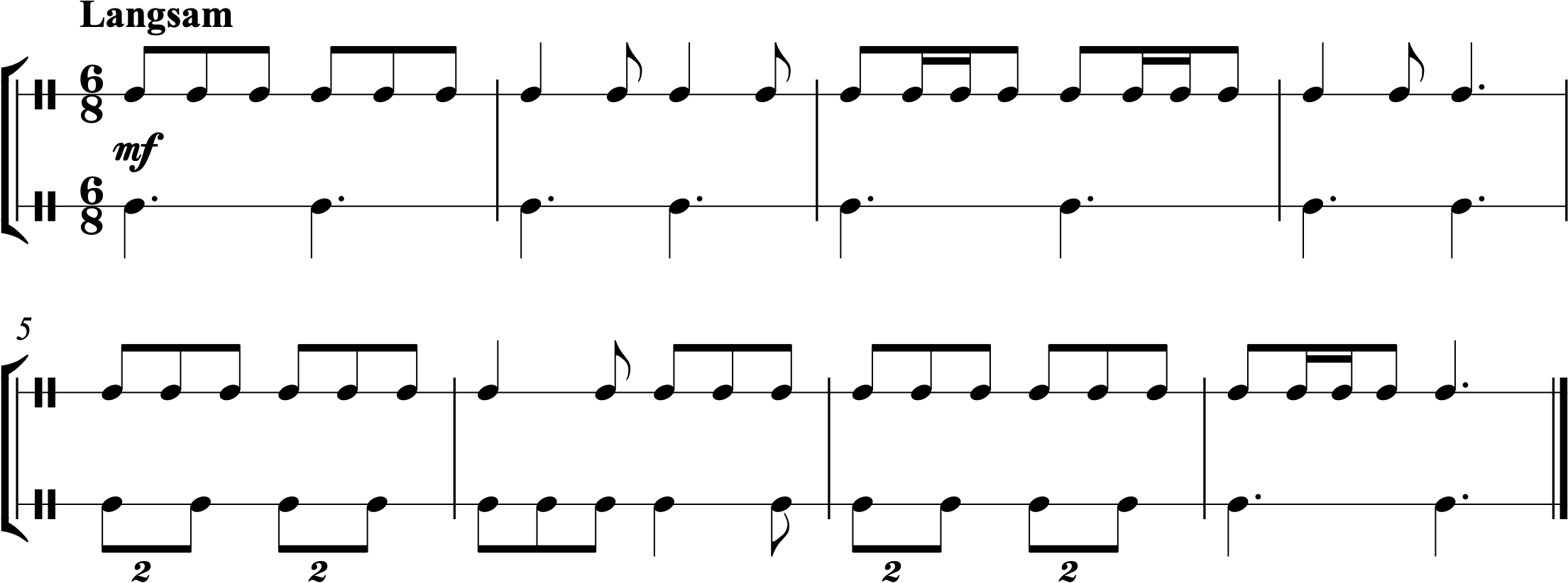

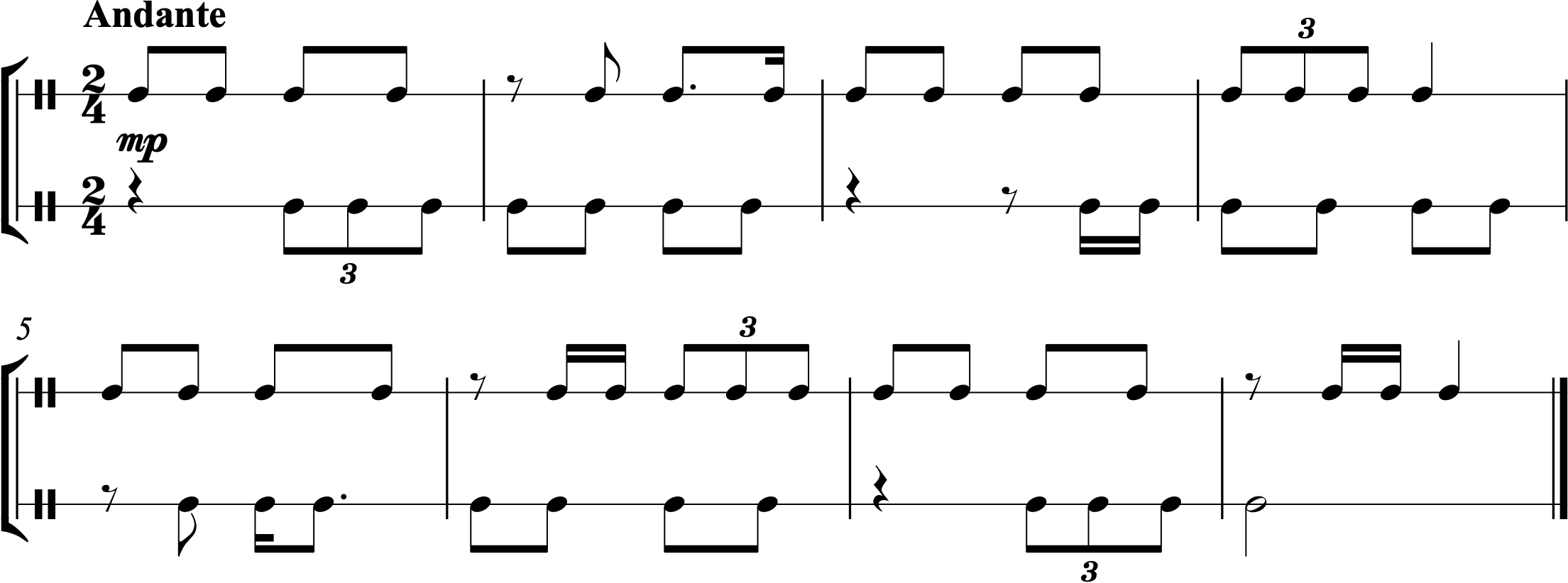

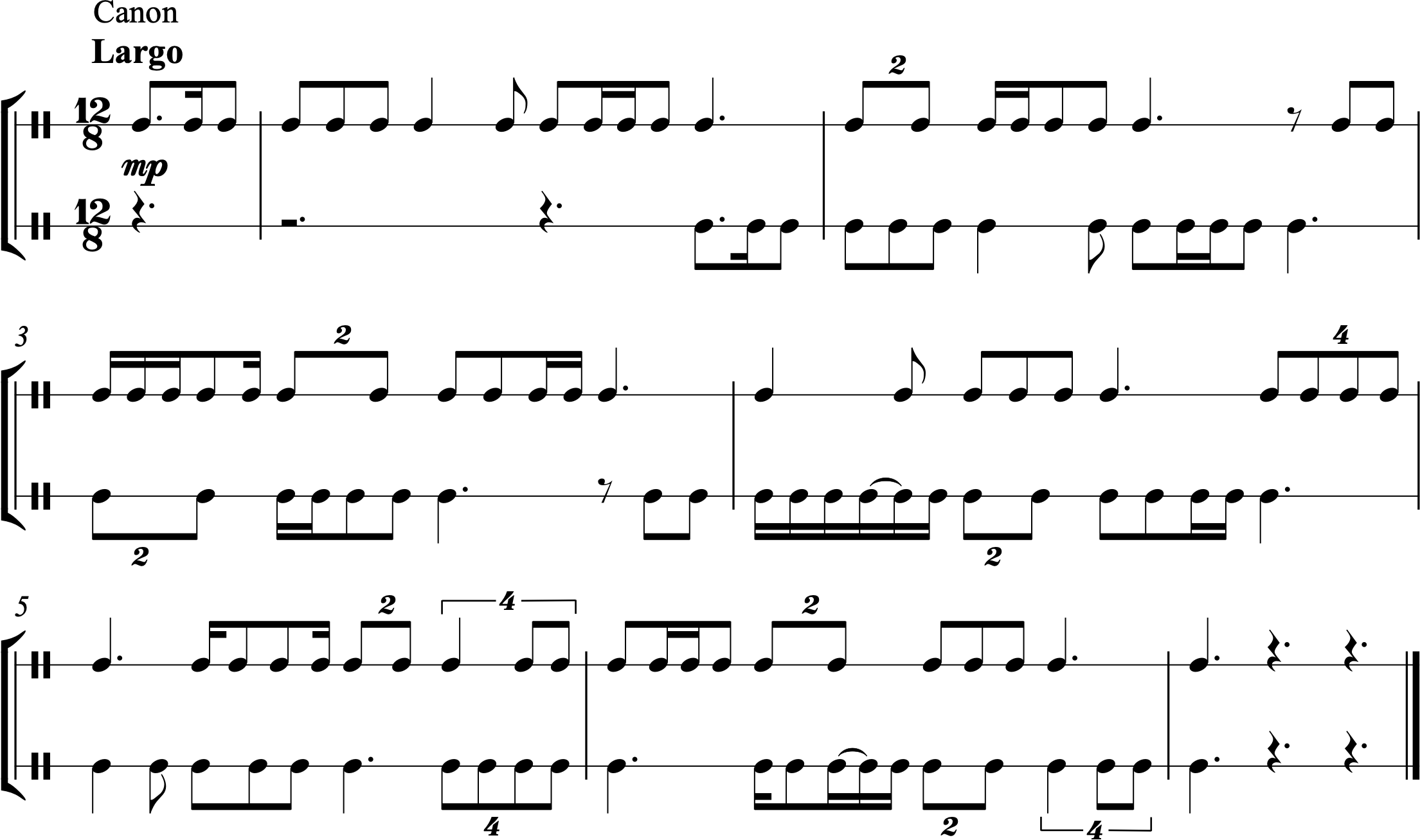

Section A—Two-against-three polyrhythms in compound meter

Practice

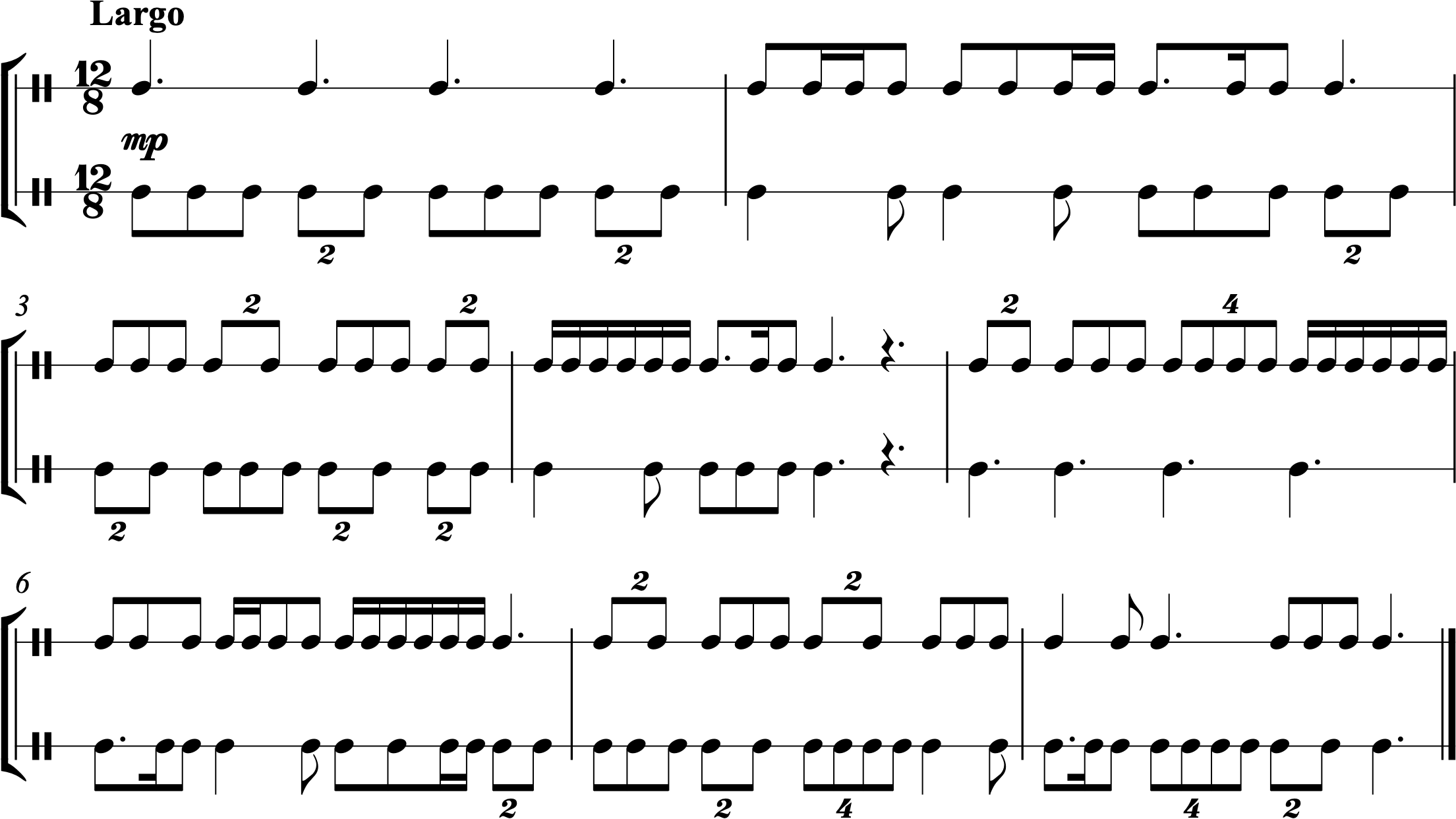

1.

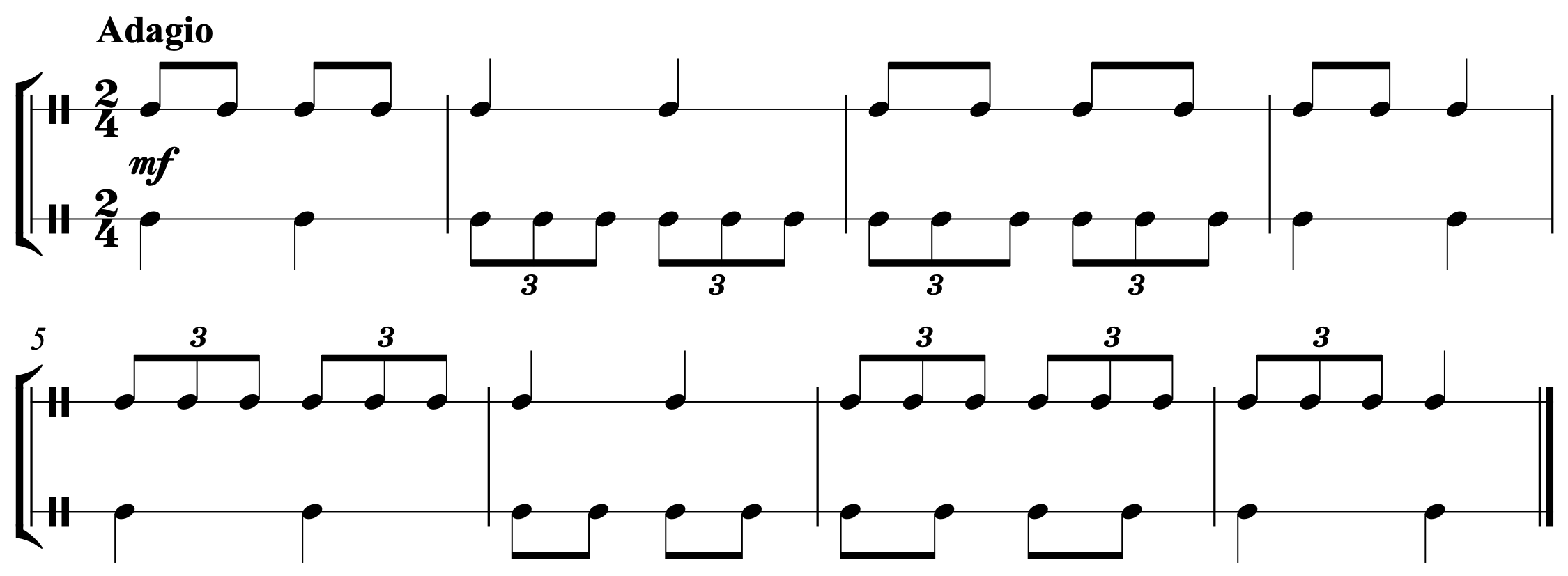

2.

3.

4.

5.

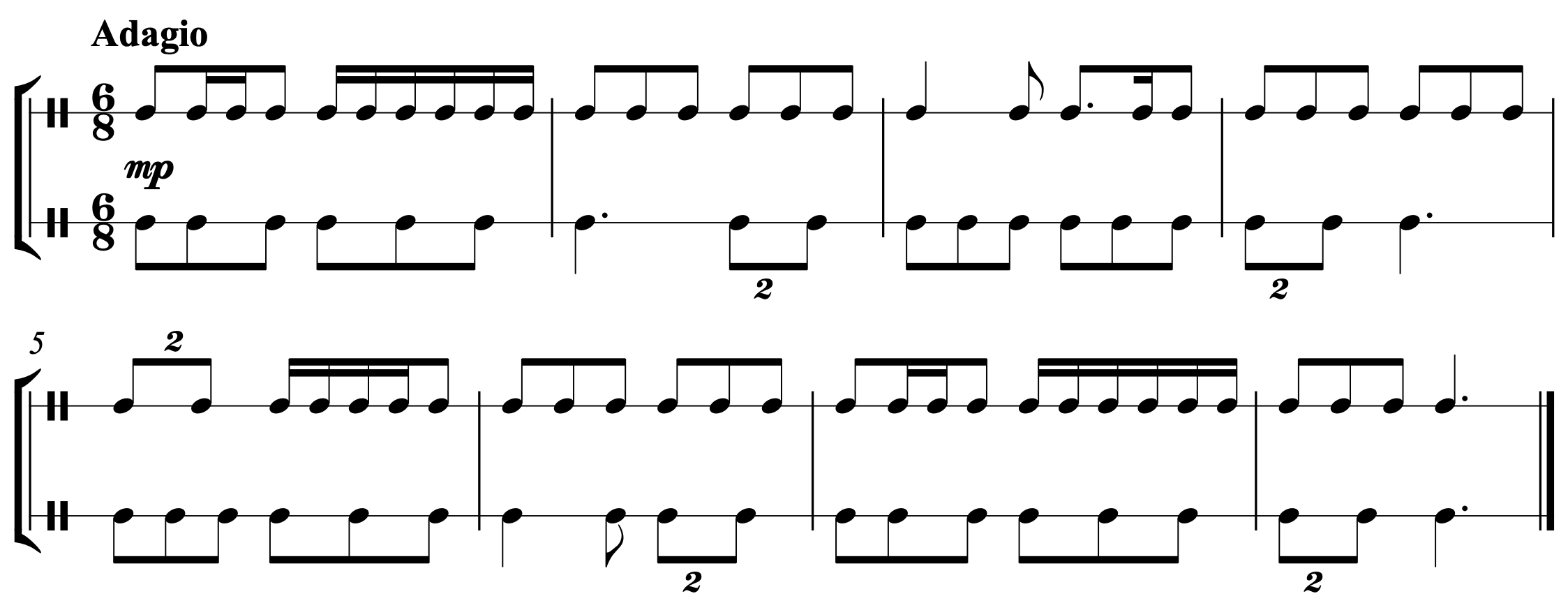

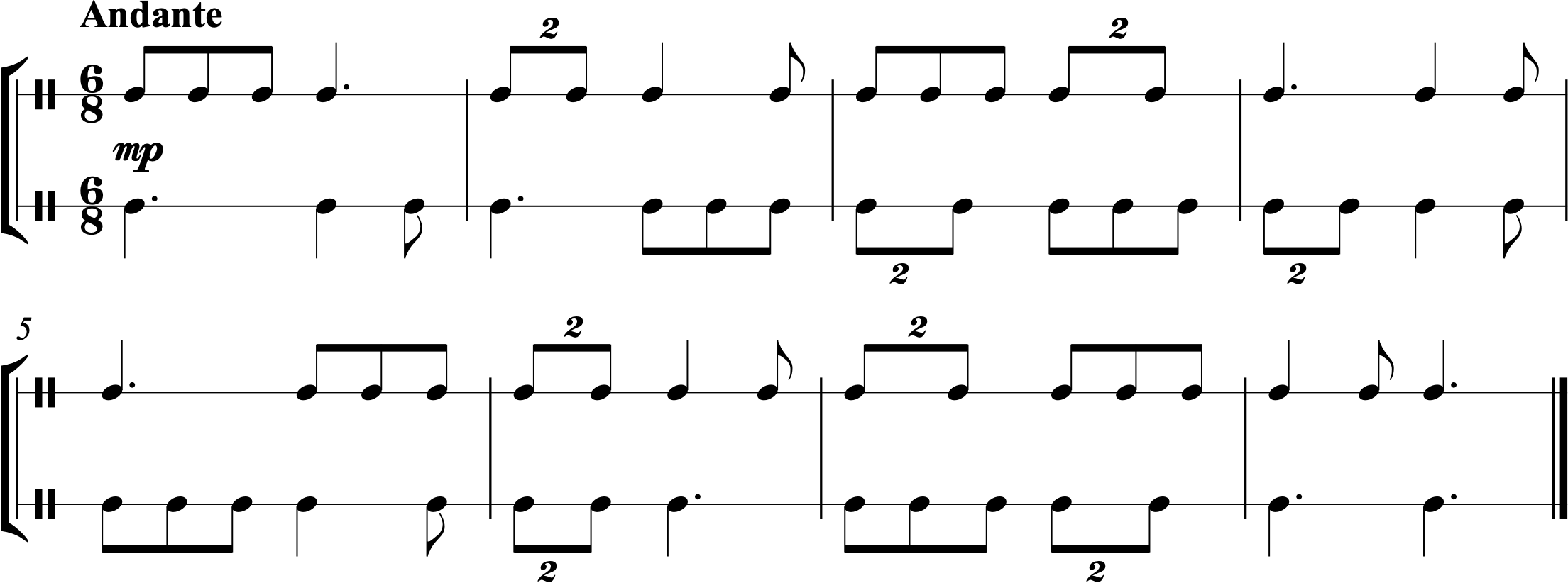

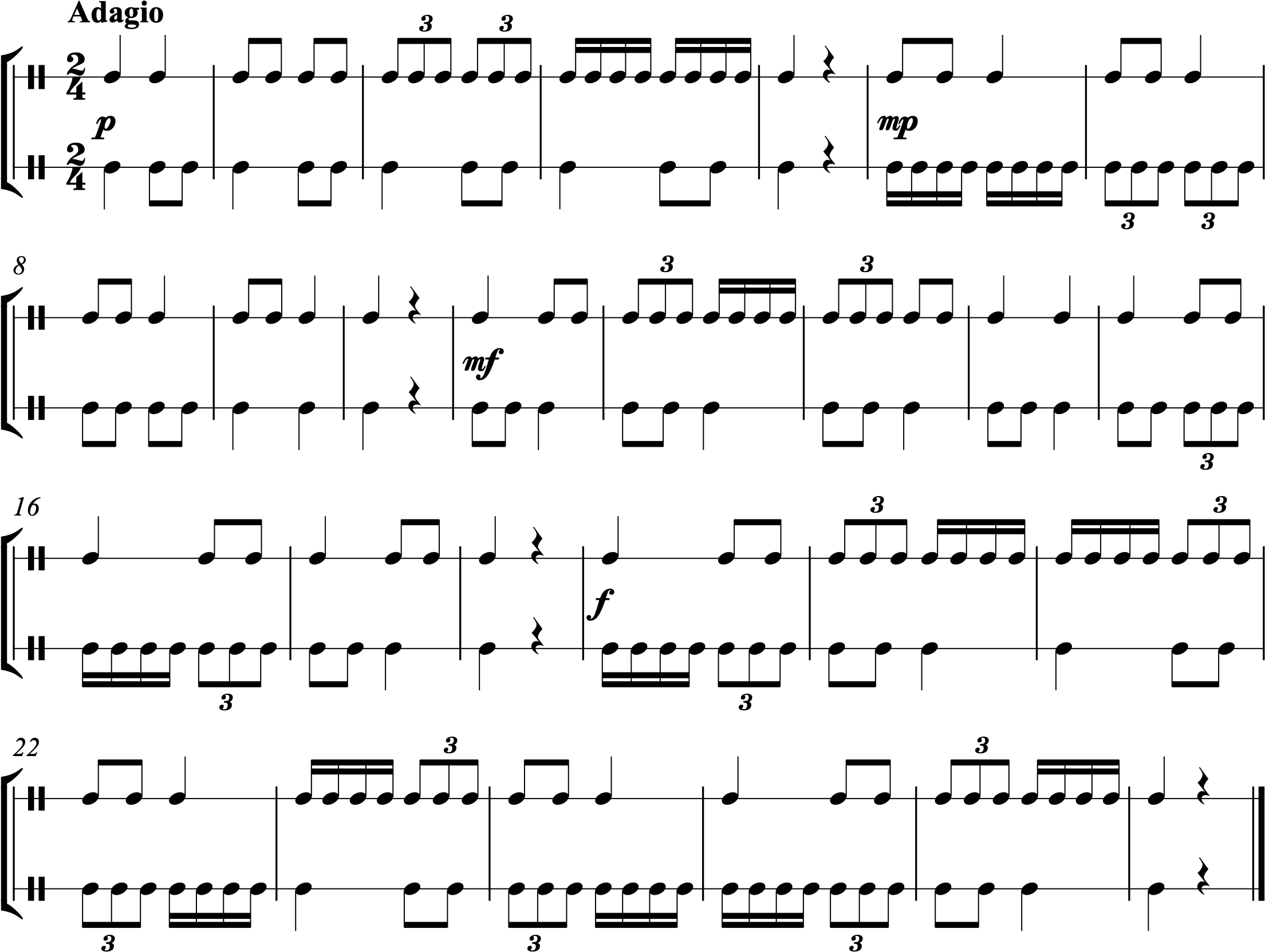

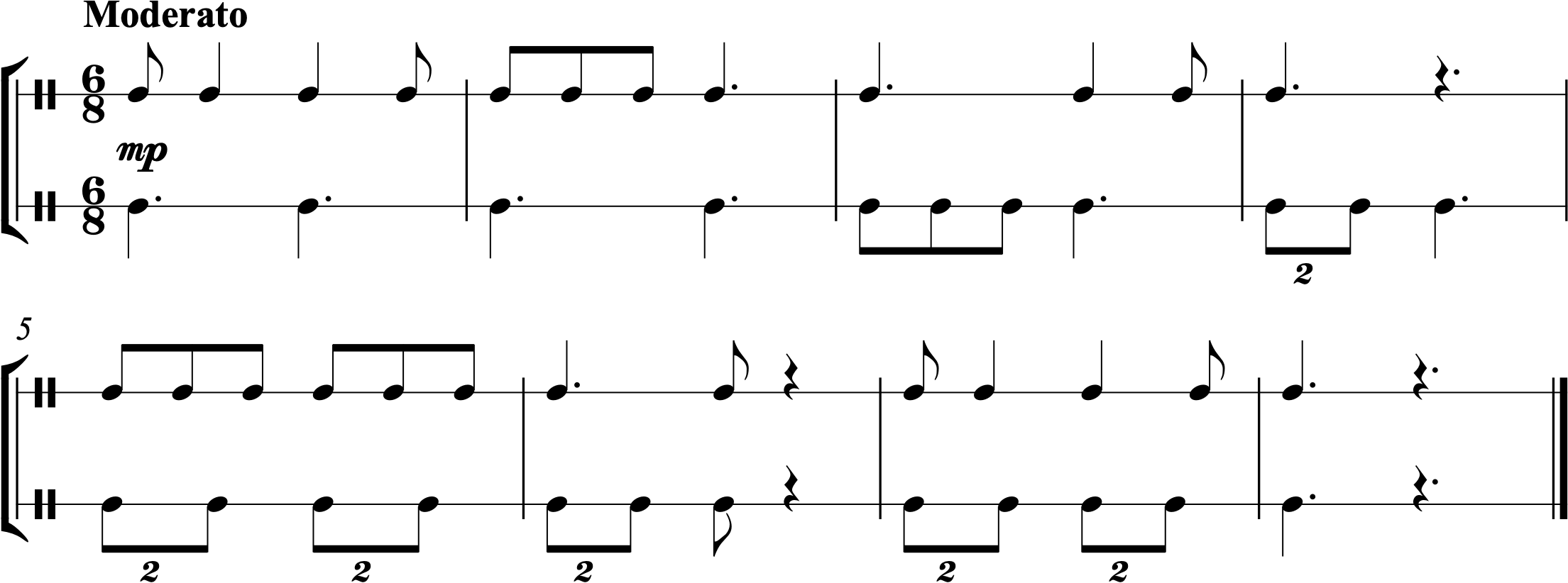

Section B—Three-against-two polyrhythms in simple meter

Practice

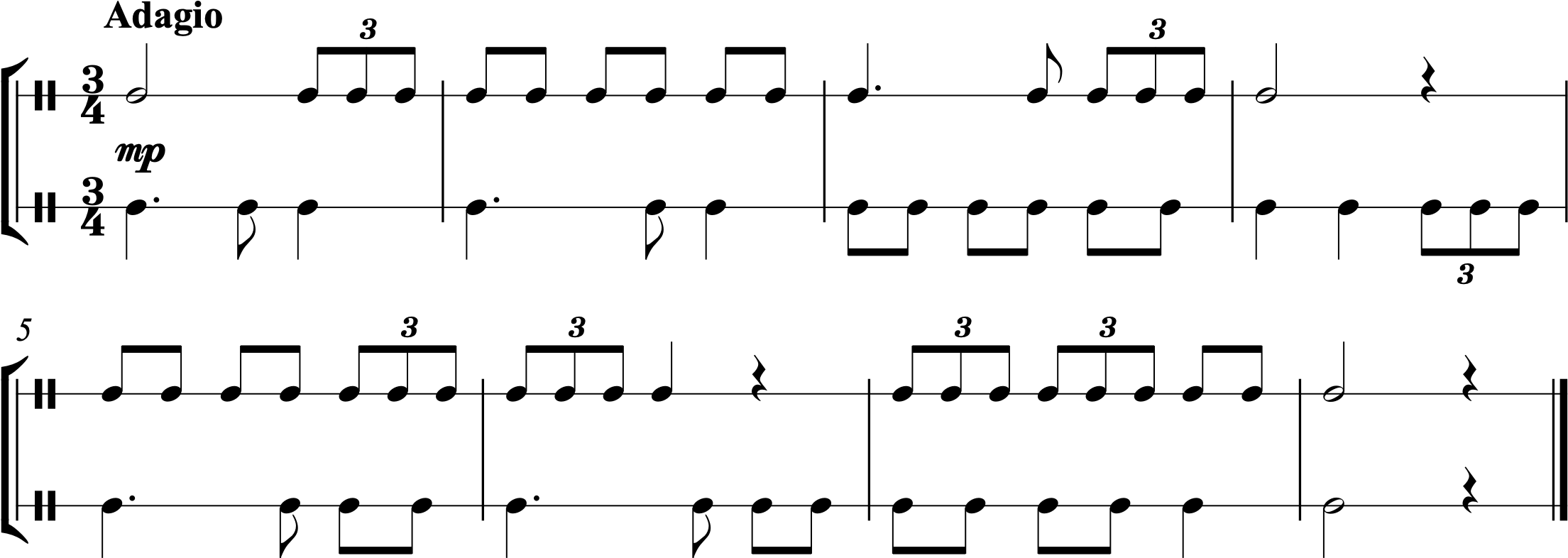

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

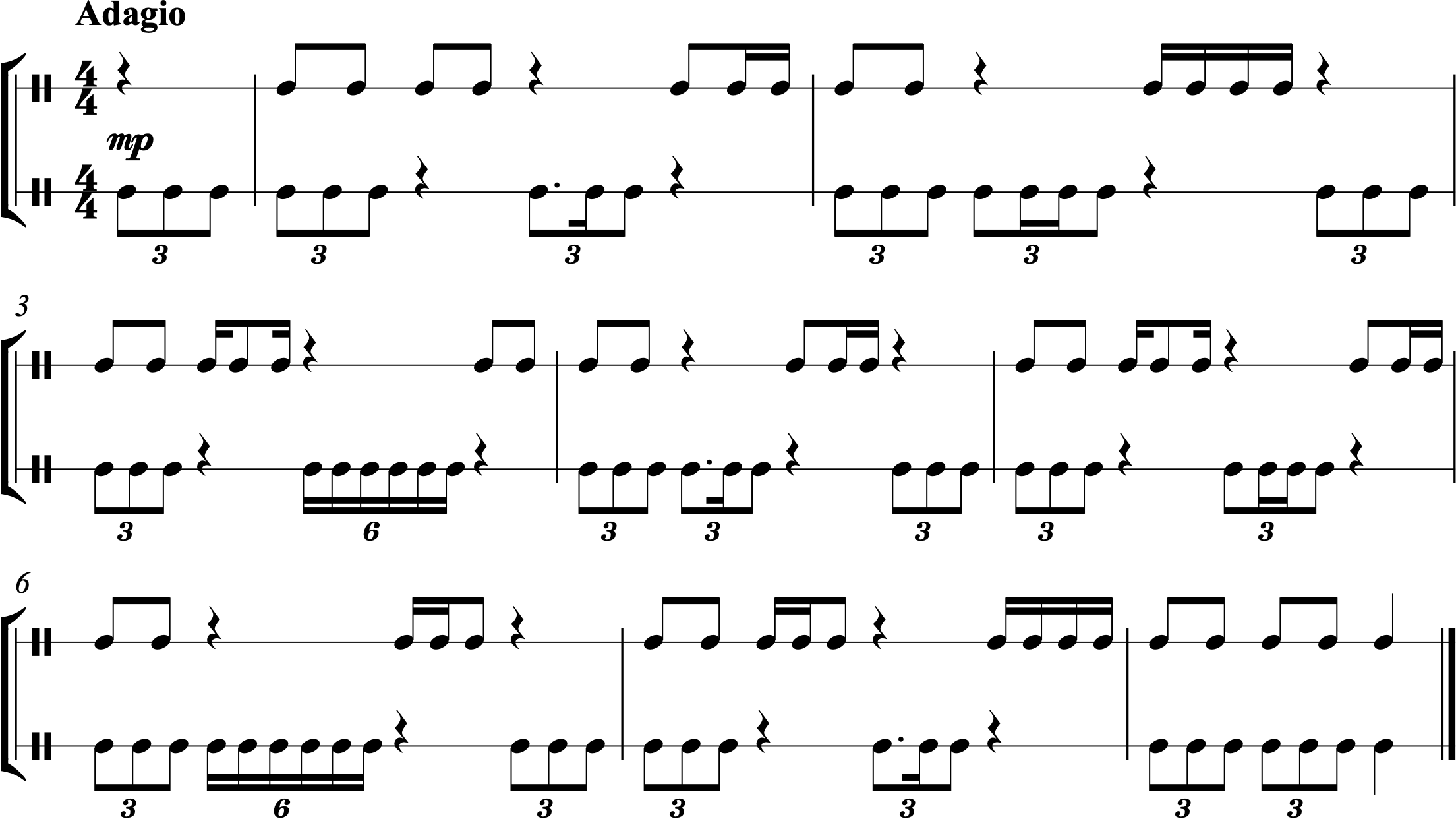

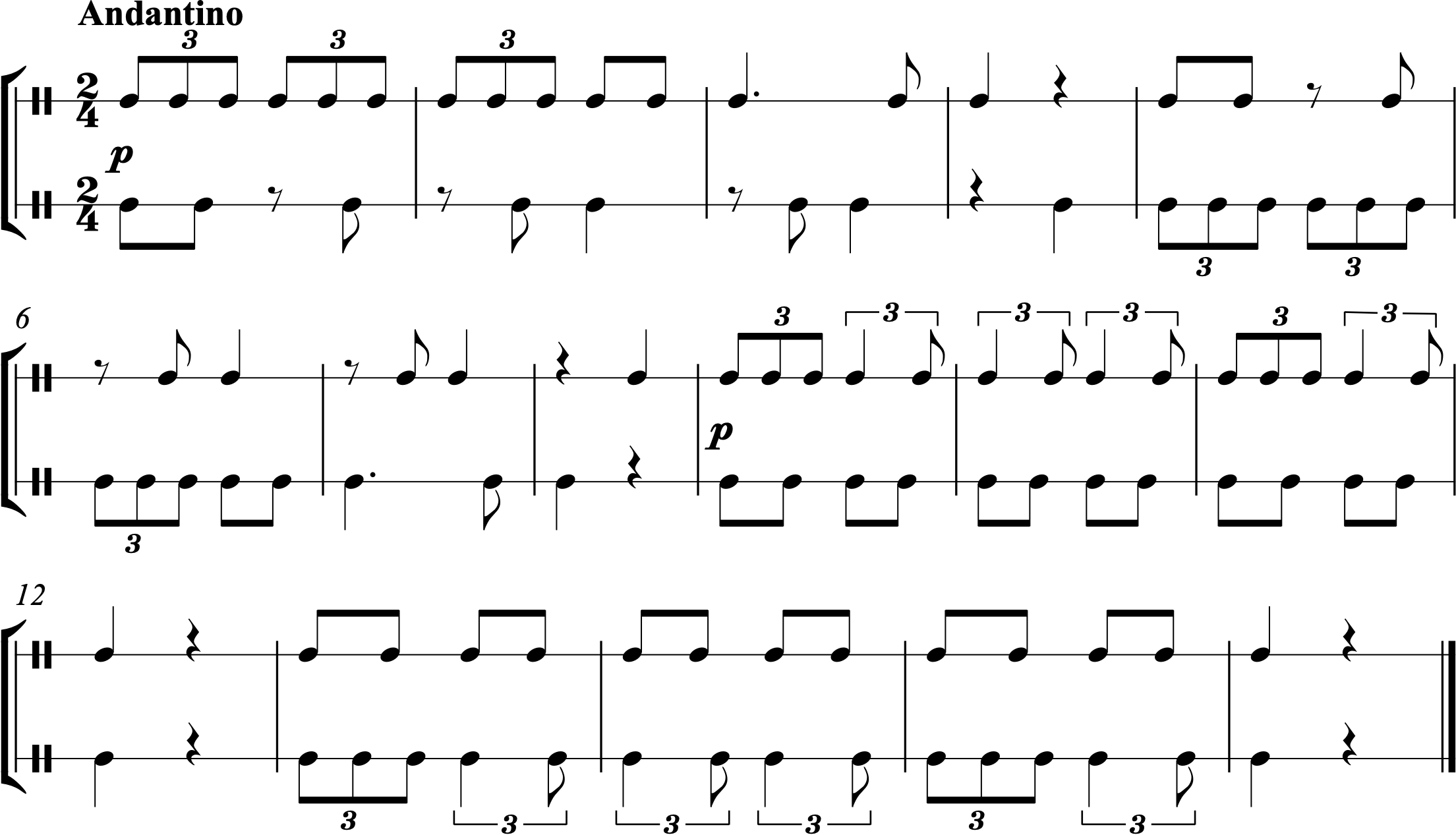

Section C—More two-against-three and three-against-two polyrhythms

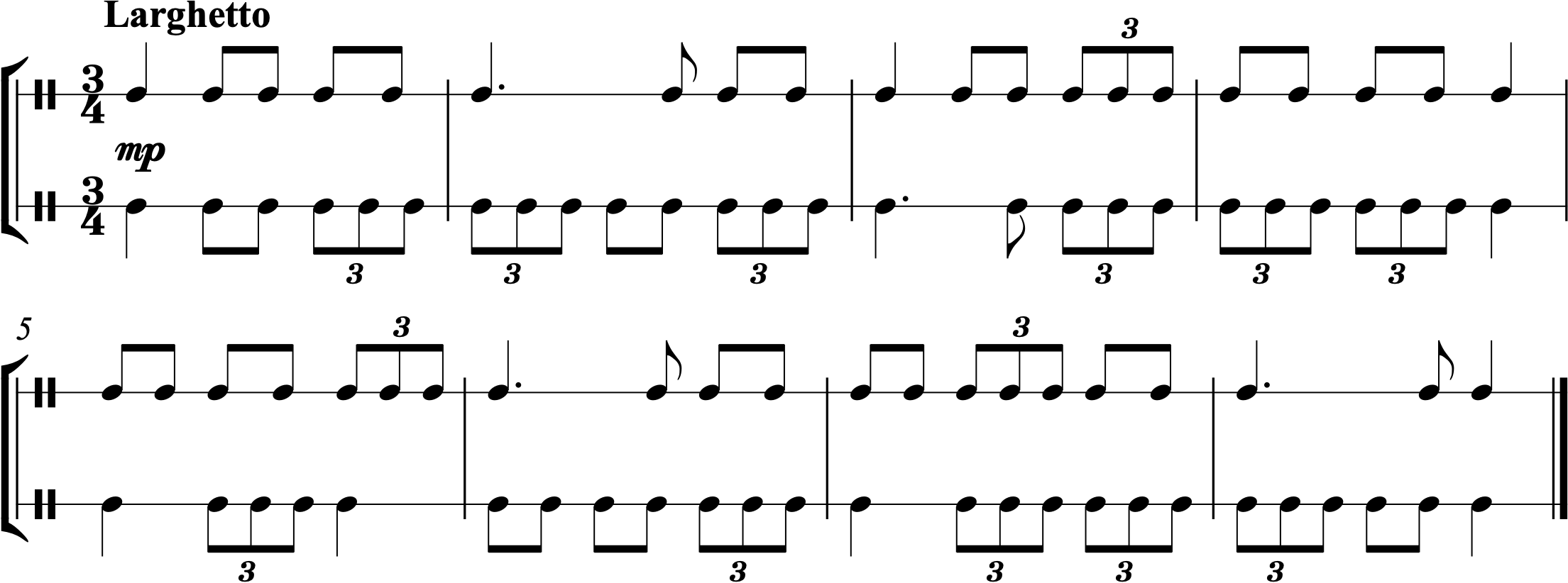

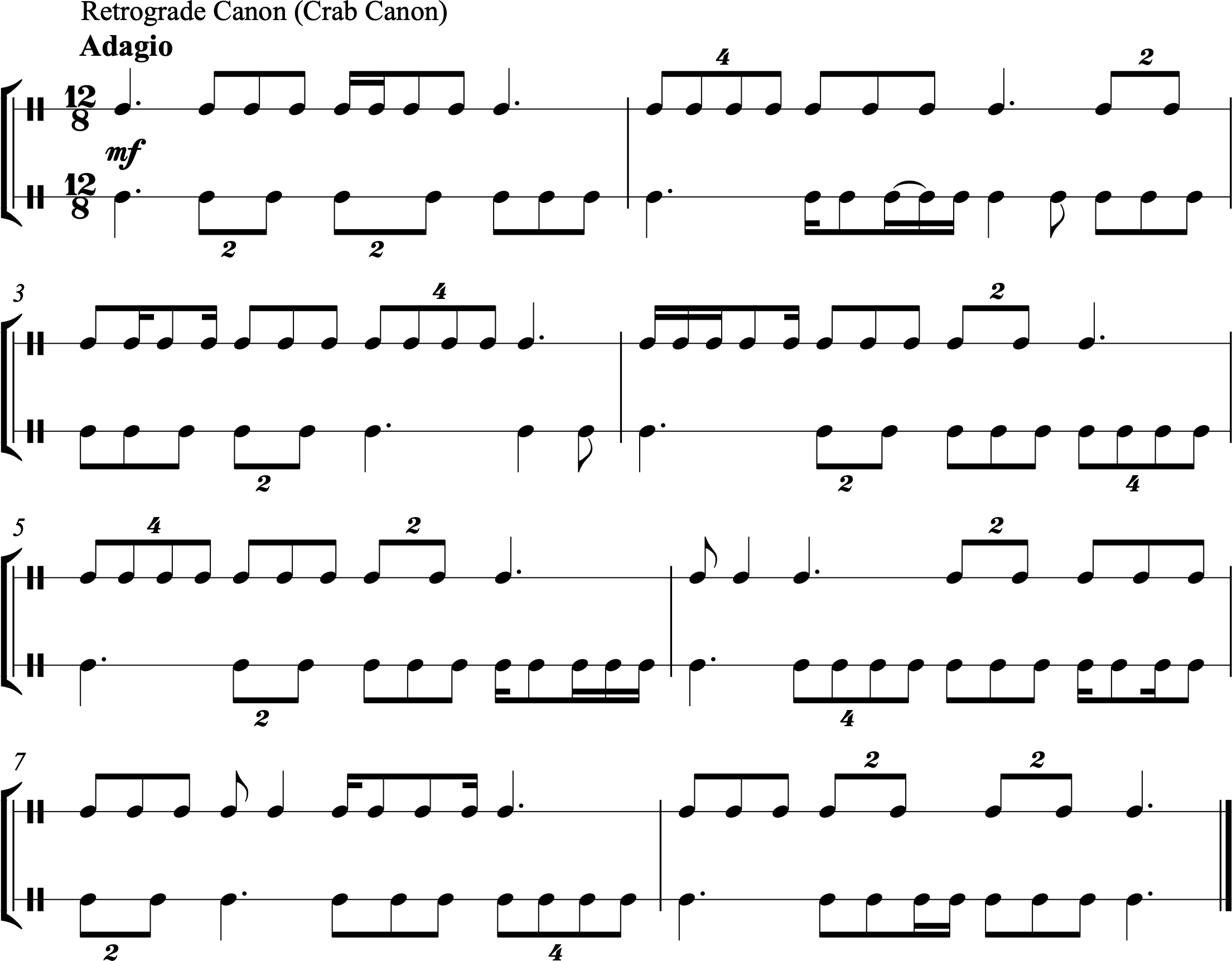

12.

13.

14.

15.

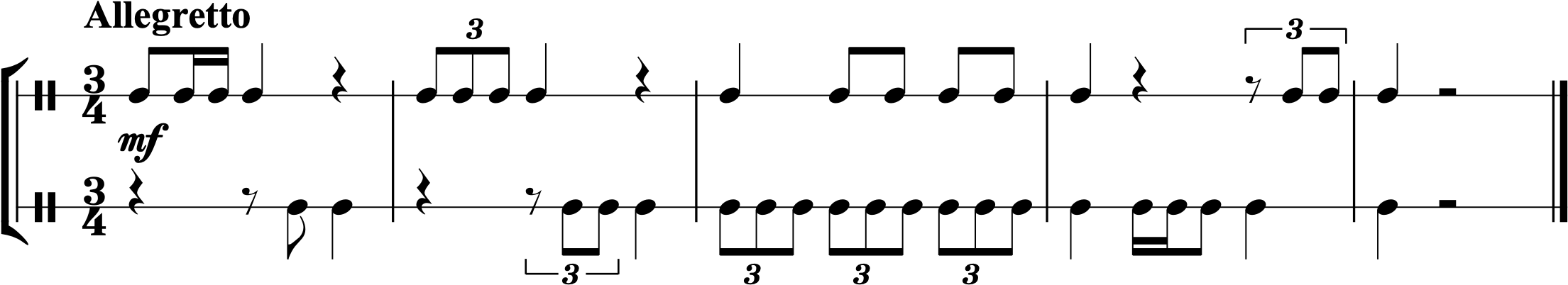

16.

17.

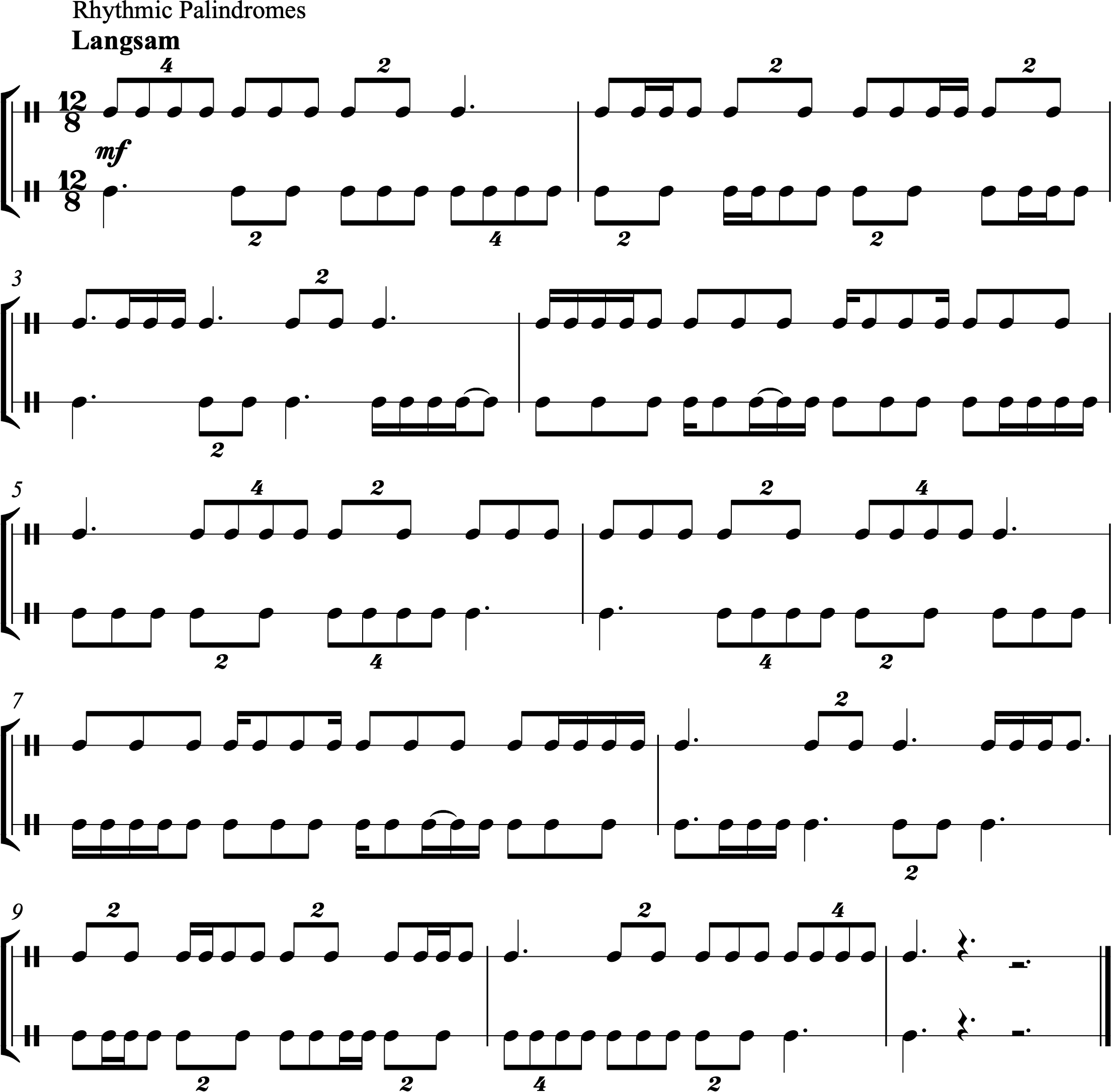

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

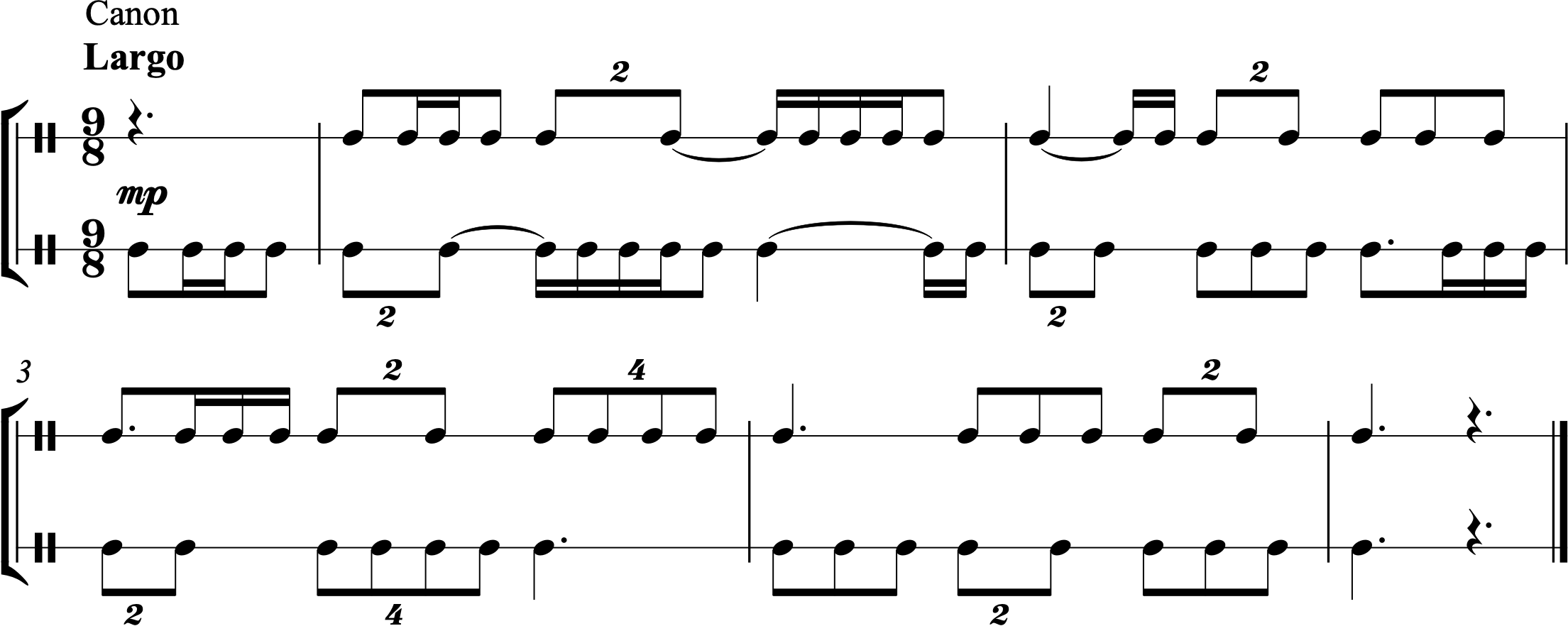

26.

27.

28.

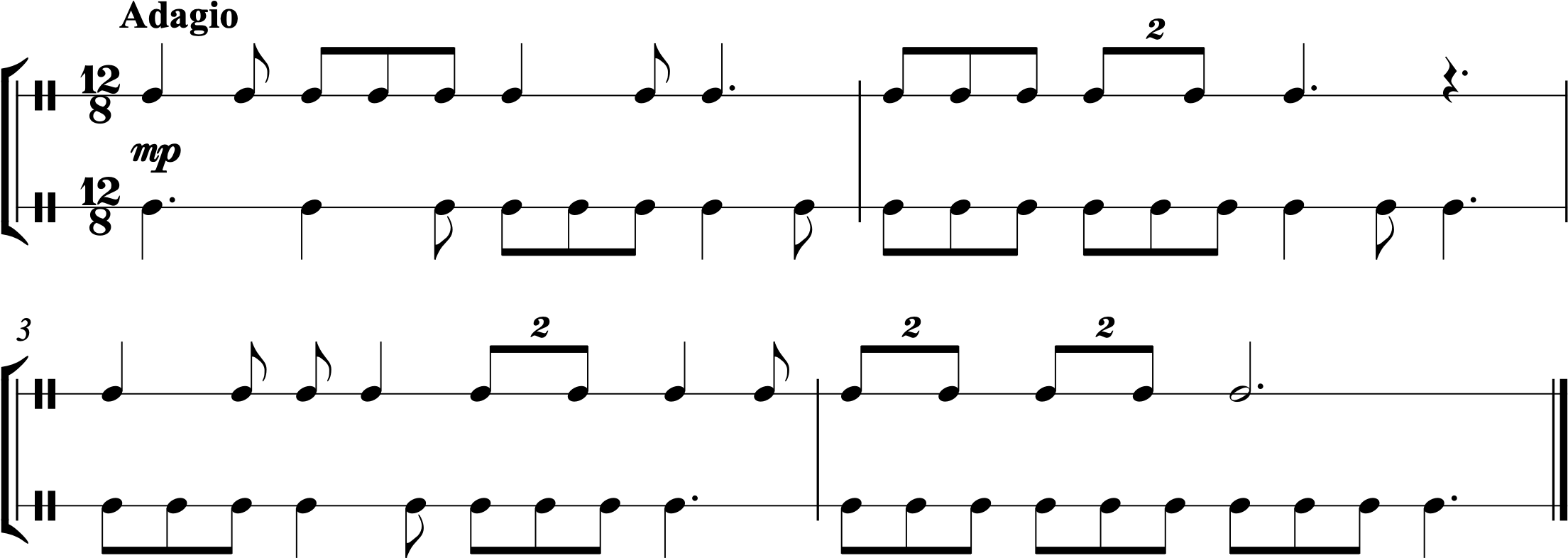

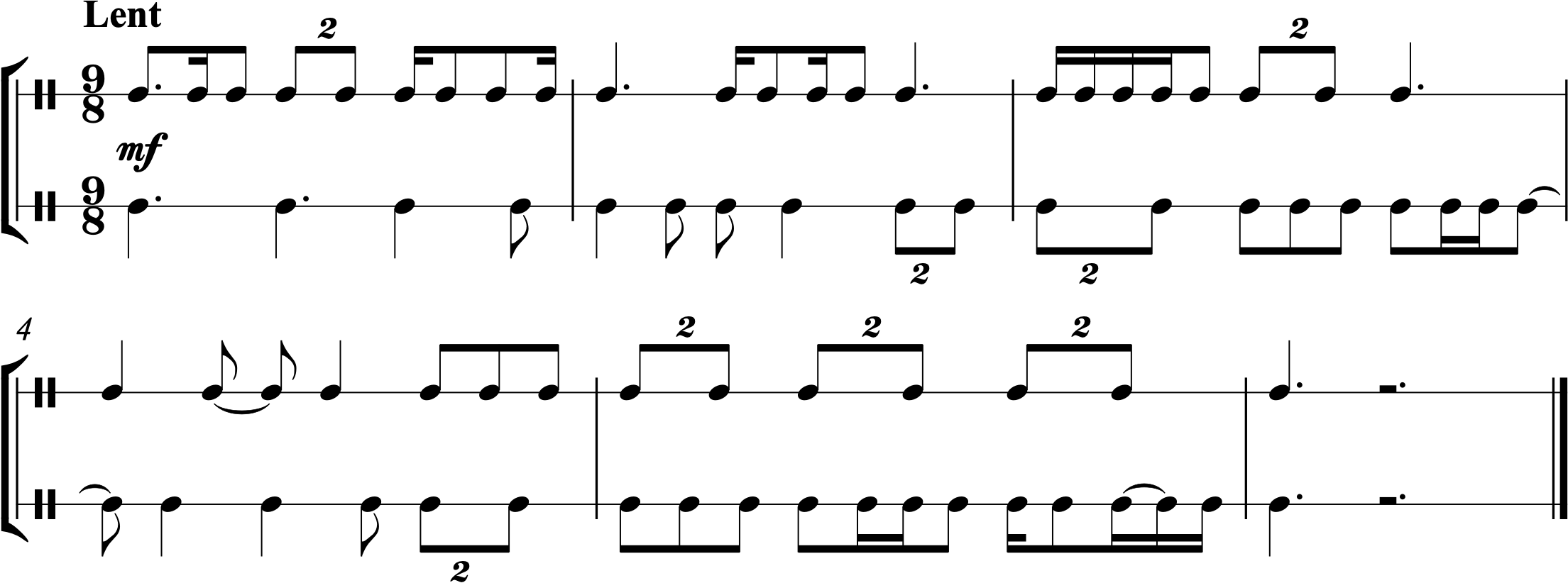

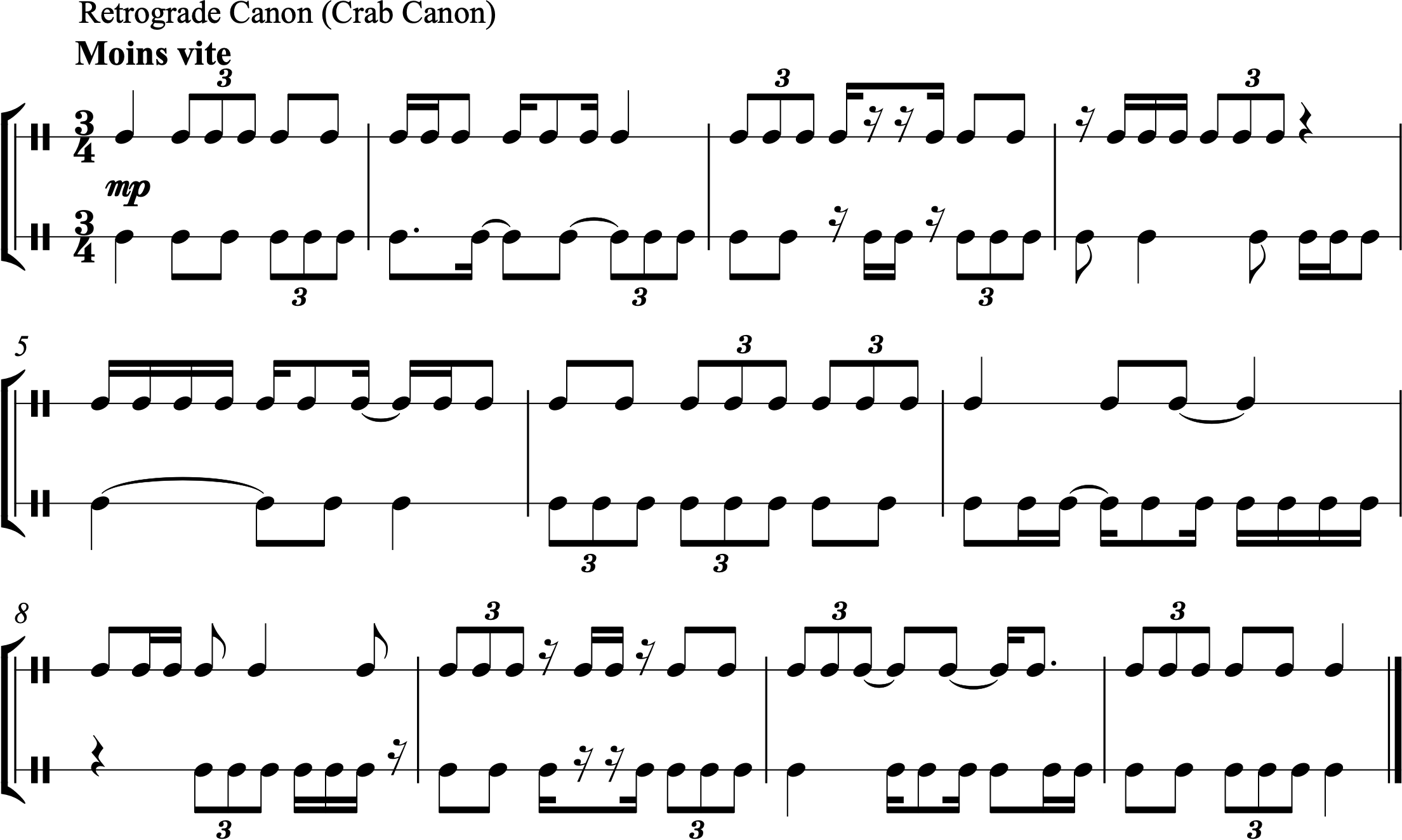

Section D—Incomplete two-against-three and three-against-two polyrhythms

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

Rhythmic Cells

- For general suggestions on how to use these rhythmic cells, see Appendix: How to Use Rhythmic Cells.

Rhythm in Context

In the 18th prelude from Scriabin’s (1872–1915) 24 Preludes, op. 11, the two hands of the pianist are frequently in a 3:2 polyrhythm against each other. This excerpt begins with triplets in the left hand and eighth notes in the right hand, but they switch later in the excerpt. You can hear the piece in the YouTube video below. Underneath that, you can see the score for measures 6–23. This movement is quite fast—Allegro agitato—so you may want to adjust the playback speed of the YouTube video to start. As you listen, try performing along in one or more of the following ways:

- Speak the rhythm of the right hand on rhythmic syllables

- Speak the rhythm of the left hand on rhythmic syllables

- Speak the rhythm of one hand while tapping the rhythm of the other

- Tap the rhythm of both hands together

Citations

Poem:

- Eliza Paul Kirkbride Gurney (1801–1888), “All Alone,” public domain. From Heart Utterances at Various Periods of a Chequered Life, unpublished.

Psalm:

- Scripture taken from the KJV, 1987, public domain.

Rhythm in Context:

- Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915), 24 Preludes, op. 11, no. 18, written between 1888–1896.