20 Dante’s Purgatorio Canti 10-11-12

These are canti I refer to as the “creative canti,” where Dante explores the nature of his creative act of writing, and clergie, and the importance of rooting that practice in humility. This consideration will help us situate the tale of Cadmus in relationship to the tale of Phaethon in Book 1, and reflect upon our role as students engaged in the Great Texts tradition.

Canto 10

WHEN we had crossed the threshhold of the door [1]

Which the perverted love of souls disuses,

Because it makes the crooked way seem straight,

Re-echoing I heard it closed again;

And if I had turned back mine eyes upon it,

What for my failing had been fit excuse?

We mounted upward through a rifted rock,

Which undulated to this side and that,

Even as a wave receding and advancing.

“Here it behoves us use a little art,”

Began my Leader, “to adapt ourselves

Now here, now there, to the receding side.”

And this our footsteps so infrequent made,

That sooner had the moon’s decreasing disk [2]

Regained its bed to sink again to rest,

Than we were forth from out that needle’s eye;

But when we free and in the open were

There where the mountain backward piles itself,

I wearied out, and both of us uncertain

About our way, we stopped upon a plain

More desolate than roads across the deserts.

From where its margin borders on the void,

To foot of the high bank that ever rises,

A human body three times told would measure;

And far as eye of mine could wing its flight,

Now on the left, and on the right flank now,

The same this cornice did appear to me.

Thereon our feet had not been moved as yet,

When I perceived the embankment round about,

Which all right of ascent had interdicted,[3]

To be of marble white, and so adorned

With sculptures, that not only Polycletus,[4]

But Nature’s self, had there been put to shame.

The Angel, who came down to earth with tidings

Of peace, that had been wept for many a year,

And opened Heaven from its long interdict,

In front of us appeared so truthfully

There sculptured in a gracious attitude,

He did not seem an image that is silent.

One would have sworn that he was saying, “Ave”;[5]

For she was there in effigy portrayed

Who turned the key to ope the exalted love,

And in her mien this language had impressed,

“Ecce ancilla Dei,” as distinctly[6]

As any figure stamps itself in wax.

Keep not thy mind upon one place alone,”

The gentle Master said, who had me standing

Upon that side where people have their hearts;

Whereat I moved mine eyes, and I beheld

In rear of Mary, and upon that side

Where he was standing who conducted me,

Another story on the rock imposed;

Wherefore I passed Virgilius and drew near,

So that before mine eyes it might be set.

There sculptured in the self-same marble were

The cart and oxen, drawing the holy ark,

Wherefore one dreads an office not appointed.[7]

People appeared in front, and all of them

In seven choirs divided, of two senses

Made one say “No,” the other, “Yes, they sing.”

Likewise unto the smoke of the frankincense,

Which there was imaged forth, the eyes and nose

Were in the yes and no discordant made.

Preceded there the vessel benedight,

Dancing with girded loins, the humble Psalmist,[8]

And more and less than King was he in this.

Opposite, represented at the window

Of a great palace, Michal looked upon him,[9]

Even as a woman scornful and afflicted.

I moved my feet from where I had been standing,

To examine near at hand another story

Which after Michal glimmered white upon me.

There the high glory of the Roman Prince[10]

Was chronicled, whose great beneficence

Moved Gregory to his great victory;[11]

’Tis of the Emperor Trajan I am speaking;

And a poor widow at his bridle stood,

In attitude of weeping and of grief.

Around about him seemed it thronged and full

Of cavaliers, and the eagles in the gold

Above them visibly in the wind were moving.

The wretched woman in the midst of these

Seemed to be saying: “Give me vengeance, Lord,

For my dead son, for whom my heart is breaking”

And he to answer her: “Now wait until

I shall return.”And she: “My Lord,” like one

In whom grief is impatient, “shouldst thou not

Return?” And he: “Who shall be where I am

Will give it thee.” And she: “Good deed of others

What boots it thee, if thou neglect thine own?”

Whence he: “Now comfort thee, for it behoves me

That I discharge my duty ere I move;

Justice so wills, and pity doth retain me.”

He who on no new thing has ever looked

Was the creator of this visible language,

Novel to us, for here it is not found.

While I delighted me in contemplating

The images of such humility,

And dear to look on for their Maker’s sake,

“Behold, upon this side, but rare they make

Their steps,” the Poet murmured, “many people,

These will direct us to the lofty stairs.”

Mine eyes, that in beholding were intent

To see new things, of which they curious are,

In turning round towards him were not slow.

But still I wish not, Reader, thou shouldst swerve

From thy good purposes, because thou hearest

How God ordaineth that the debt be paid;

Attend not to the fashion of the torment,

Think of what follows; think that at the worst

It cannot reach beyond the mighty sentence.

“Master,” began I, “that which I behold

Moving towards us seems to me not persons,

And what I know not, so in sight I waver.”

And he to me: “The grievous quality

Of this their torment bows them so to earth,

That my own eyes at first contended with it;

But look there fixedly, and disentangle

By sight what cometh underneath those stones;

Already canst thou see how each is stricken.”

O ye proud Christians! wretched, weary ones!

Who, in the vision of the mind infirm

Confidence have in your backsliding steps,

Do ye not comprehend that we are worms,

Born to bring forth the angelic butterfly

That flieth unto judgment without screen?

Why floats aloft your spirit high in air?

Like are ye unto insects undeveloped

Even as the worm in whom formation fails!

As to sustain a ceiling or a roof,

In place of corbel, oftentimes a figure

Is seen to join its knees unto its breast,

Which makes of the unreal real anguish

Arise in him who sees it, fashioned thus

Beheld I those, when I had ta’en good heed.

True is it, they were more or less bent down,

According as they more or less were laden;

And he who had most patience in his looks

Weeping did seem to say, “I can no more!”

Canto 11

“OUR Father, thou who dwellest in the heavens,

Not circumscribed, but from the greater love

Thou bearest to the first effects on high,[12]

Praised be thy name and thine omnipotence

By every creature, as befitting is

To render thanks to thy sweet effluence.

Come unto us the peace of thy dominion,

For unto it we cannot of ourselves,

If it come not, with all our intellect.

Even as thine own Angels of their will

Make sacrifice to thee, Hosanna singing,

So may all men make sacrifice of theirs.

Give unto us this day our daily manna,

Withouten which in this rough wilderness

Backward goes he who toils most to advance.

And even as we the trespass we have suffered

Pardon in one another, pardon thou

Benignly, and regard not our desert.

Our virtue, which is easily o’ercome,

Put not to proof with the old Adversary,

But thou from him who spurs it so, deliver.

This last petition verily, dear Lord,

Not for ourselves is made, who need it not,

But for their sake who have remained behind us.”

Thus for themselves and us good furtherance

Those shades imploring, went beneath a weight

Like unto that of which we sometimes dream,

Unequally in anguish round and round

And weary all, upon that foremost cornice,

Purging away the smoke-stains of the world

If there good words are always said for us,

What may not here be said and done for them,

By those who have a good root to their will?

Well may we help them wash away the marks

That hence they carried, so that clean and light

They may ascend unto the starry wheels!

“Ah! so may pity and justice you disburden

Soon, that ye may have power to move the wing,

That shall uplift you after your desire,

Show us on which hand tow’rd the stairs the way

Is shortest, and if more than one the passes,

Point us out that which least abruptly falls;

For he who cometh with me, through the burden

Of Adam’s flesh wherewith he is invested,

Against his will is chary of his climbing.”

The words of theirs which they returned to those

That he whom I was following had spoken,

It was not manifest from whom they came,

But it was said: “To the right hand come with us

Along the bank, and ye shall find a pass

Possible for living person to ascend.

And were I not impeded by the stone,

Which this proud neck of mine doth subjugate,

Whence I am forced to hold my visage down,

Him, who still lives and does not name himself,

Would I regard, to see if I may know him

And make him piteous unto this burden.

A Latian was I, and born of a great Tuscan;[13]

Guglielmo Aldobrandeschi was my father;

I know not if his name were ever with you.

The ancient blood and deeds of gallantry

Of my progenitors so arrogant made me

That, thinking not upon the common mother,

All men I held in scorn to such extent

I died therefor, as know the Sienese,

And every child in Campagnatico.

I am Omberto; and not to me alone

Has pride done harm, but all my kith and kin

Has with it dragged into adversity.

And here must I this burden bear for it

Till God be satisfied, since I did not

Among the living, here among the dead.”

Listening I downward bent my countenance;

And one of them, not this one who was speaking,

Twisted himself beneath the weight that cramps him,

And looked at me, and knew me, and called out,

Keeping his eyes laboriously fixed

On me, who all bowed down was going with them.

“O,” asked I him, “art thou not Oderisi,

Agobbio’s honour, and honour of that art

Which is in Paris called illuminating?”[14]

“Brother,” said he, “more laughing are the leaves

Touched by the brush of Franco Bolognese;[15]

All his the honour now, and mine in part.

In sooth I had not been so courteous

While I was living, for the great desire

Of excellence, on which my heart was bent.

Here of such pride is paid the forfeiture;

And yet I should not be here, were it not

That, having power to sin, I turned to God.

O thou vain glory of the human powers,

How little green upon thy summit lingers,

If ’t be not followed by an age of grossness!

In painting Cimabue thought that he

Should hold the field, now Giotto has the cry,

So that the other’s fame is growing dim.

So has one Guido from the other taken[16]

The glory of our tongue, and he perchance

Is born, who from the nest shall chase them both.[17]

Naught is this mundane rumour but a breath

Of wind, that comes now this way and now that,

And changes name, because it changes side.

What fame shalt thou have more, if old peel off

From thee thy flesh, than if thou hadst been dead

Before thou left the pappo and the dindi,[18]

Ere pass a thousand years? which is a shorter

Space to the eterne, than twinkling of an eye

Unto the circle that in heaven wheels slowest.[19]

With him, who takes so little of the road[20]

In front of me, all Tuscany resounded;

And now he scarce is lisped of in Siena,

Where he was lord, what time was overthrown[21]

The Florentine delirium, that superb

Was at that day as now ’tis prostitute.

Your reputation is the colour of grass

Which comes and goes, and that discolours it

By which it issues green from out the earth.”

And I: “Thy true speech fills my heart with good

Humility, and great tumour thou assuagest;

But who is he, of whom just now thou spakest?”

“That,” he replied, “is Provenzan Salvani,[22]

And he is here because he had presumed

To bring Siena all into his hands.

He has gone thus, and goeth without rest

E’er since he died; such money renders back

In payment he who is on earth too daring.”

And I: “If every spirit who awaits

The verge of life before that he repent,

Remains below there and ascends not hither,

Unless good orison shall him bestead,

Until as much time as he lived be passed,

How was the coming granted him in largess?”

“When he in greatest splendour lived,” said he,

“Freely upon the Campo of Siena,

All shame being laid aside, he placed himself;

And there to draw his friend from the duress

Which in the prison-house of Charles he suffered,

He brought himself to tremble in each vein.

I say no more, and know that I speak darkly;

Yet little time shall pass before thy neighbours

Will so demean themselves that thou canst gloss it.[23]

This action has released him from those confines.”

Canto 12

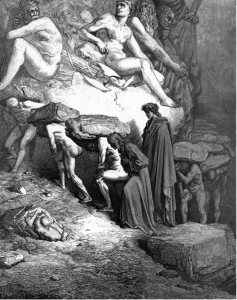

ABREAST, like oxen going in a yoke,[24]

I with that heavy-laden soul went on,

As long as the sweet pedagogue permitted;[25]

But when he said, “Leave him, and onward pass,

For here ’tis good that with the sail and oars,

As much as may be, each push on his barque;”

Upright, as walking wills it, I redressed

My person, notwithstanding that my thoughts

Remained within me downcast and abashed.

I had moved on, and followed willingly

The footsteps of my Master, and we both

Already showed how light of foot we were,

When unto me he said: “Cast down thine eyes;

’Twere well for thee, to alleviate the way,

To look upon the bed beneath thy feet.”

As, that some memory may exist of them

Above the buried dead their tombs in earth[26]

Bear sculptured on them what they were before;

Whence often there we weep for them afresh,

From pricking of remembrance, which alone

To the compassionate doth set its spur;

So saw I there, but of a better semblance

In point of artifice, with figures covered

Whate’er as pathway from the mount projects.

I saw that one who was created noble[27]

More than all other creatures, down from heaven

Flaming with lightnings fall upon one side.[28]

I saw Briareus smitten by the dart[29]

Celestial, lying on the other side,

Heavy upon the earth by mortal frost.

I saw Thymbraeus, Pallas saw, and Mars,[30]

Still clad in armour round about their father,

Gaze at the scattered members of the giants.

I saw, at foot of his great labour, Nimrod,[31]

As if bewildered, looking at the people

Who had been proud with him in Sennaar.[32]

O Niobe! with what afflicted eyes

Thee I beheld upon the pathway traced

Between thy seven and seven children slain![33]

O Saul! how fallen upon thy proper sword[34]

Didst thou appear there lifeless in Gilboa,

That felt thereafter neither rain nor dew![35]

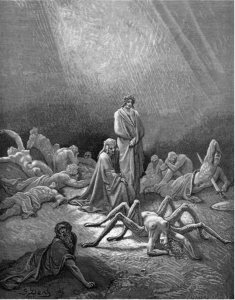

O mad Arachne! so I thee beheld[36]

E’en then half spider, sad upon the shreds

Of fabric wrought in evil hour for thee!

O Rehoboam! no more seems to threaten[37]

Thine image there; but full of consternation

A chariot bears it off, when none pursues!

Displayed moreo’er the adamantine pavement

How unto his own mother made Alcmaeon[38]

Costly appear the luckless ornament;

Displayed how his own sons did throw themselves

Upon Sennacherib within the temple,[39]

And how, he being dead, they left him there;

Displayed the ruin and the cruel carnage

That Tomyris wrought, when she to Cyrus said,[40]

“Blood didst thou thirst for, and with blood I glut thee!”

Displayed how routed fled the Assyrians

After that Holofernes had been slain,[41]

And likewise the remainder of that slaughter

I saw there Troy in ashes and in caverns;[42]

O Ilion! thee, how abject and debased,

Displayed the image that is there discerned!

Whoe’er of pencil master was or stile,

That could portray the shades and traits which there

Would cause each subtile genius to admire?

Dead seemed the dead, the living seemed alive;

Better than I saw not who saw the truth,

All that I trod upon while bowed I went.

Now wax ye proud, and on with looks uplifted,

Ye sons of Eve, and bow not down your faces

So that ye may behold your evil ways!

More of the mount by us was now encompassed,

And far more spent the circuit of the sun,

Than had the mind preoccupied imagined,

When he, who ever watchful in advance

Was going on, began: “Lift up thy head,

’Tis no more time to go thus meditating

Lo there an Angel who is making haste

To come towards us; lo, returning is

From service of the day the sixth handmaiden,[43]

With reverence thine acts and looks adorn,

So that he may delight to speed us upward;

Think that this day will never dawn again.”

I was familiar with his admonition

Ever to lose no time; so on this theme

He could not unto me speak covertly.

Towards us came the being beautiful

Vested in white, and in his countenance

Such as appears the tremulous morning star.

His arms he opened, and opened then his wings;

“Come,” said he, “near at hand here are the steps,

And easy from henceforth is the ascent.”

At this announcement few are they who come!

O human creatures, born to soar aloft,

Why fall ye thus before a little wind?

He led us on to where the rock was cleft;

There smote upon my forehead with his wings,

Then a safe passage promised unto me.

As on the right hand, too ascent the mount

Where seated is the church that lordeth

O’er the well-guided, above Rubaconte,[44]

The bold abruptness of the ascent is broken

By stairways that were made there in the age

When still were safe the ledger and the stave,

E’en thus attempered is the bank which falls

Sheer downward from the second circle there

But on this, side and that the high rock graze

As we were turning thitherward our persons.

”Beati pauperes spiritu,” voices[45]

Sang in such wise that speech could tell it not.

Ah me! how different are these entrances

From the Infernal! for with anthems here

One enters, and below with wild laments.

We now were hunting up the sacred stairs,

And it appeared to me by far more easy

Than on the plain it had appeared before.

Whence I: “My Master, say, what heavy thing

Has been uplifted from me, so that hardly

Aught of fatigue is felt by me in walking?”

He answered: “When the P’s which have remained

Still on thy face almost obliterate

Shall wholly, as the first is, be erased,

Thy feet will be so vanquished by good will,

That not alone they shall not feel fatigue,

But urging up will be to them delight.”

Then did I even as they do who are going

With something on the head to them unknown,

Unless the signs of others make them doubt,

Wherefore the hand to ascertain is helpful,

And seeks and finds, and doth fulfill the office

Which cannot be accomplished by the sight;

And with the fingers of the right hand spread

I found but six the letters, that had carved

Upon my temples he who bore the keys;

Upon beholding which my Leader smiled.

Source: Divine Comedy – Purgatory by Dante Alighieri, translated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, illustrations by Paul Gustave Doré (https://www.paskvil.com › dante-02-purgatorio)

- In this canto is described the First Circle of Purgatory, where the sin Pride is punished. ↵

- It being now Easter Monday, and the fourth day after the full moon, the hour here indicated would be four hours after sunrise. And as the sun was more than two hours high when Dante found himself at the gate of Purgatory (Canto IX.), he was an hour and a half in this needle’s eye. ↵

- Which was so steep as to allow of no ascent; dritto di salita being used in the sense of right of way. ↵

- Polycletus, the celebrated Grecian sculptor, among whose works one, representing the body-guard of the king of Persia, acquired such fame for excellence as to be called “the Rule.” ↵

- Luke I. 28: “And the angel came in unto her and said, Hail, thou that art highly favoured, the Lord is with thee.” ↵

- Luke I. 38: “And Mary said, Behold the handmaid of the Lord.” ↵

- 2 Samuel VI. 6, 7: “And when they came to Nachon’s threshing-floor, Uzzah put forth his hand to the ark of God, and took hold of it; for the oxen shook it. And the anger of the Lord was kindled against Uzzah, and God smote him there for his error; and there he died by the ark of God.” ↵

- 2 Samuel VI. 14: “And David glanced before the Lord with all his might; and David was girded with a linen ephod.” ↵

- 2 Samuel VI. 16: “And as the ark of the Lord came into the city of David, Michal, Saul’s daughter, looked through a window and saw King David leaping and daii mg before the Lord; and she despised him in her heart.” ↵

- This story of Trajan is told in nearly the same words, though in prose, in the Fiore di Filosofi, a work attributed to Brunetto Latini. See Nannucci, Manuale della Letteratura del Primo Secolo, III. 291. It may be found also in the Legenda Aurea, in the Cento Novelle Antiche, Nov. 67, and in the Life of St. Gregory, by Paulus Diaconus. ↵

- Gregory’s “great victory” was saving the soul of Trajan by prayer. ↵

- The angels, the first creation or effects of the divine power. ↵

- Or Italian. The speaker is Omberto Aldobrandeschi, Count of Santafiore, in the Maremma of Siena. “The Counts of Santafiore were, and are, and almost always will be at war with the Sienese,” says the Ottimo. In one of these wars Omberto was slain, at the village of Campagnatico. “The author means,” continues the same commentator, “that he who cannot carry his head high should bow it down like a bulrush.” ↵

- The art of illuminating manuscripts, which was called in Paris alluminare, was in Italy called miniare. Hence Oderigi is called by Vasari a miniatore, or miniature-painter. ↵

- Franco Bolognese was a pupil of Oderigi, who perhaps alludes to this fact in claiming a part of the honour paid to the younger artist. ↵

- Probably Dante’s friend, Guido Cavalcanti, Inferno X.; and Guido Guinicelli, Purgato- rio XXVI. ↵

- Some commentators suppose that Dante here refers to himself. He more probably is speaking only in general terms, without particular reference to any one. ↵

- The babble of childhood; pappa for pane, bread, and dindi for danari, money. Halliwell, Dic. of Arch. and Prov. Words: “DINDERS, small coins of the Lower Empire, found at Wroxeter.” ↵

- The revolution of the fixed stars, according to the Ptolemaic theory, which was also Dante’s, was thirty-six thousand years. ↵

- “Who goes so slowly,” interprets the Ottimo. ↵

- At the battle of Monte Aperto. See note in Inferno X. ↵

- A haughty and ambitious nobleman of Siena, who led the Sienese troops at the battle of Monte Aperto. Afterwards, when the Sienese were routed by the Florentines at the battle of Colle in the Val d’ Eisa, (see note in Purgatorio XIII.) he was taken prisoner “and his head was cut off,” says Villani, VII. 31, “and carried through all the camp fixed upon a lance. And well was fulfilled the prophecy and revelation which the devil had made to him, by means of necromancy, but which he did not understand; for the devil, being constrained to tell how he would succeed in that battle, mendaciously answered, and said: ‘Thou shalt go forth and fight, thou shalt conquer not die in the battle, and thy head shall be highest in the camp.’ And he, believing from these words that he should be victorious, and believing that he should be lord over all did not put a stop after ‘not’ (vincerai no, morrai – thou shalt conquer not, thou shalt die). And therefore it is great folly to put faith in the devil’s advice. This Messer Provenzano was a great man in Siena after his victory at Monte Aperto, and led the whole city, and all the Ghibelline party of Tuscany made him their chief, and he was very presumptuous in his will.” The humility which saved him was his seating himself at a little table in the public square of Siena, called the Campo, and begging money of all passers to pay the ransom of a friend who had been taken prisoner by Charles of Anjou, as here narrated by Dante. ↵

- A prophecy of Dante’s banishment and poverty and humiliation. ↵

- n the first part of this canto the same subject is continued, with examples of pride humbled, sculptured on the pavement, upon which the proud are doomed to gaze as they go with their heads bent down beneath their heavy burdens, – “So that they may behold their evil ways.” ↵

- In Italy a pedagogue is not only a teacher, but literally a leader of children, and goes from house to house collecting his little flock, which he brings home again after school. ↵

- Tombs under the pavement in the aisles of churches, in contradistinction to those built aloft against the walls. ↵

- The reader will not fail to mark the artistic structure of the passage from this to the sixty-third line. First there four stanzas beginning, “I saw;” then four beginning, “O;” then four beginning, “Displayed;” and then a stanza which resumes and unites them all. ↵

- Luke X. 18: “I beheld Satan as lightning fall from heaven.” ↵

- liad, I. 403: “Him of hundred hands, whom the gods call Briareus. and all men Aegaeon.” See note in Inferno XXI. He was struck by the thunderbolt of Jove, or by a shaft of Apollo, at the battle of Flegra. “Ugly medley of sacred and profane, of revealed truth and fiction!” exclaims Venturi. ↵

- Thymbraeus, a surname of Apollo, from his temple in Thymbra. ↵

- Nimrod, who “began to be a mighty one in the earth,” and his “tower whose top may reach unto heaven.” See also note in Inferno XXXI. ↵

- Lombardi proposes in this line “together” instead of “proud”; which Biagioli thinks is “changing beautiful diamond for a bit of lead; a stupid is he who accepts the change.” ↵

- Homer, Iliad, XXIV. 604 makes them but twelve. “Twelve children perished in her halls, six daughters and six blooming sons; these Apollo slew from his silver bow, en- raged with Niobe; and those Diana, delighting in arrows, because she had deemed her- self equal to the beautiful-checked Latona. She said that Latona had borne only two, but she herself had borne many ; nevertheless those, though but two, exterminated all these.” But Ovid, Metamorph., VI., says: – “Seven are my daughters of a form divine, With seven fair sons, an indefective line.” ↵

- 1 Samuel XXXI. 4, 5: “Then said Saul unto his armour-bearer, Draw thy sword and thrust me through therewith, lest these uncircumcised come and thrust me through and abuse me. But his armour-bearer would not, for he was sore afraid; therefore Saul took a sword, and fell upon it. And when his armour-bearer saw that Saul was dead, he fell, likewise upon his sword, and died with him.” ↵

- 2 Samuel I. 21: “Ye mountain of Gilboa, let there be no dew, neither let there be rain upon you.” ↵

- Arachne, daughter of Idmon the dyer of Colophon. ↵

- In the revolt of the Ten Tribes. 1 Kings XII. 18: “Then King Rehoboam sent Adoram, who was over the tribute; and all Israel stoned him with stones, that he died; therefore King Rehoboam made speed to get him up to his chariot, to flee to Jerusalem.” ↵

- Amphiaraus, the soothsayer, foreseeing his own death if he went to the Theban war, concealed himself, to avoid going. His wife Eriphyle, bribed by a “golden necklace set with diamonds,” betrayed to her brother Adrastus his hiding-place, and Amphiaraus, departing, charged his son Alcmeon to kill Eriphyle as soon as he heard of his death. ↵

- Isaiah XXXVII. 38: “And it came to pass, as he was worshipping in the house of Nis- roch his god, that Adrammelech and Sharezer, his sons, smote him with the sword; and they escaped into the land of Armenia, and Esarhaddon, his son, reigned in his stead.” ↵

- Herodotus, Book I. Ch. 214, Rawlinson’s Tr.: “Tomyris, when she found that Cyrus paid no heed to her advice, collected all the forces of her kingdom, and gave him battle Of all the combats in which the barbarians have engaged among themselves, I reckon this to have been the fiercest... The greater part of the army of the Persians was destroyed, and Cyrus himself fell, after reigning nine and twenty years. Search was made among the slain, by order of the queen, for the body of Cyrus, and when it was found, she took skin, and filling it full of human blood, dipped the head of Cyrus in the gore, saying, as she thus insulted the corse, ‘I live and have conquered thee in fight, and yet by thee am I ruined; for thou tookest my son with guile; but thus I make good my threat, and give thee thy fill of blood.’ Of the many different accounts which are given of the death of Cyrus, this which I have followed appears to be the most worthy of credit.” ↵

- After Judith had slain Holofernes. Judith XV. I: “And when they that were in the tents heard, they were astonished at the thing that was done. And fear and trembling fell upon them, so that there was no man that durst abide in the sight of his neighbour, but, rushing out altogether, they fled into every way of the plain and of the hill country... Now when the children of Israel heard it, they all fell upon them with one consent, and slew them unto Chobai.” ↵

- This tercet unites the “I saw”, “O” and “Displayed” of the preceding passage, and binds the whole as with a selvage. ↵

- The sixth hour of the day, or noon of the second day. ↵

- Florence is here called ironically “the well-guided” or well governed. Rubaconte is the name of the most easterly of the bridges over the Arno, and takes its name from Messer Rubaconte, who was Podesta` of Florence in 1236, when this bridge was built. Above it on the hill stands the church of San Miniato. This is the hill which Michael Angelo fortified in the siege of Florence. In early times it was climbed by stairways. ↵

- Matthew V. 3: “Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” It must be observed that all the Latin lines in Dante should be chanted with an equal stress on each syllable, in order to make them rhythmical. ↵