33 Medea I and II in Ovid

Bk VII:1-73 Medea agonises over her love for Jason

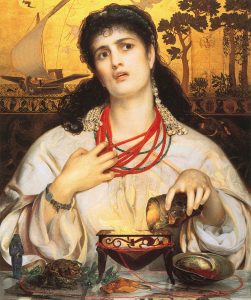

And now the Argonauts were ploughing through the sea in their ship, built in Thessalian Pagasae. They had visited Phineus, king of Thracian Salmydessus, living out a useless old age in perpetual blindness, and the winged sons of Boreas had driven the birdlike Harpies from the presence of the unhappy, aged man. At last, after enduring many trials, under their famous leader, Jason, they reached the turbulent river-waters of the muddy Phasis, in the land of Colchis. While they were standing before King Aeetes, of Aea, requesting the return of the Golden Fleece, taken from the divine ram that carried Phrixus, and while extreme terms were being imposed, involving daunting tasks, Medea, the daughter of the king, conceived an overwhelming passion for Jason. She fought against it for a time, but when reason could not overcome desire, she debated with herself.

‘Medea, you struggle in vain: some god, I do not know which, opposes you. I wonder if this, or something, like this, is what people indeed call love? Or why would the tasks my father demands of Jason seem so hard? They are more than hard! Why am I afraid of his death, when I have scarcely seen him? What is the cause of all this fear? Quench, if you can, unhappy girl, these flames that you feel in your virgin heart! If I could, I would be wiser! But a strange power draws me to him against my will. Love urges one thing: reason another. I see, and I desire the better: I follow the worse. Why do you burn for a stranger, royal virgin, and dream of marriage in an alien land? This earth can also give you what you can love. Whether he lives or dies, is in the hands of the gods. Let him live! I can pray for this even if I may not love him: what is Jason guilty of? Who, but the heartless, would not be touched by Jason’s youth, and birth, and courage? Who, though the other qualities were absent, could not be stirred by his beauty?

He has stirred my heart, indeed. And unless I offer my help, he will feel the fiery breath of the bronze-footed bulls; have to meet that enemy, sprung from the soil, born of his own sowing; or be given as captured prey to the dragon’s greed. If I allow this, then I am born of the tigress: then I show I have a heart of stone and iron! Why can I not watch him die, and shame my eyes by seeing? Why do I not urge the bulls on, to meet him, and the wild earth-born warriors, and the unsleeping dragon? Let the gods also desire the better! Though it is not for me to pray for, but to bring about.

Shall I betray my father’s country? Shall some unknown be saved by my powers, and unhurt because of me, without me, set his sails to the wind, and be husband to another, leaving Medea to be punished? If he could do that, if he could set another woman above me, let him die, the ungrateful man! But his look, his nobility of spirit, and his graceful form, do not make me fear deceit or forgetfulness of my kindness. And he will give me his word beforehand, and I will gather the gods to witness our pledge. Why fear when it is certain? Prepare yourself, and dispel all delay: Jason will be for ever in your debt, take you to himself in sacred marriage, and through the cities of Pelasgian Greece, the crowds of women will glorify you as his saviour.

Carried by the winds, shall I leave my native country, my sister, my brother, my father, and my gods? Well then, my father is barbarous, and my country is savage, and my brother is still a child: my sister’s prayers are for me, and the greatest god is within! I will not be leaving greatness behind, but pursuing greatness: honour as a saviour of these Achaean people, familiarity with a better land and with cities whose fame is flourishing even here, the culture and arts of those places, and the man, the son of Aeson, for whom I would barter those things that the wide world owns, joined to whom I will be called fortunate, dear to the gods, and my head will be crowned with the stars.

What of the stories of mountains that clash together in mid-ocean, and Charybdis the bane of sailors, now sucking in, now spewing out the sea, and rapacious dog-headed Scylla, yelping over the Sicilian deeps? Well, holding what I love, clinging to Jason’s breast, I shall be carried over the wide seas: in his arms, I will fear nothing, or if I am afraid, I will only be afraid for him.

But do you call that marriage, Medea, and clothe your fault with fair names? Consider instead, how great a sin you are near to, and while you can, shun the crime!’ She spoke, and in front of her eyes, were rectitude, piety, modesty: and now, Cupid, defeated, was turning away.

Bk VII:74-99 Jason promises to marry Medea

She went to the ancient altars of Hecate, daughter of the Titan Perses, that the shadowy grove conceals, in the remote forest. And now she was strong and her passion, now conquered, had ebbed, when she saw the son of Aeson and the flame, that was dead, relit. Her cheeks flushed, and then her whole face became pallid. Just as a tiny spark that lies buried under the ashes, takes life from a breath of air, and grows and, living, regains its previous strength, so now her calmed passion, that you would have thought had dulled, when she saw the young hero, flared up at his visible presence.

It chanced that Aeson’s son was more than usually handsome that day: you could forgive her for loving him. She gazed at him, and

fixed her eyes on him as if she had never looked at him before, and in her infatuation, seeing his face, could not believe him mortal, nor could she turn away. So that when, indeed, the stranger grasped her right hand, and began to speak, and in a submissive voice asked for her help, promising marriage, she replied in a flood of tears. ‘I see what I am doing: it is not ignorance of the truth that ensnares me, but love. Your salvation is in my gift, but being saved, remember your promise!’

He swore by the sacred rites of the Triple Goddess, by the divine presence of the grove, by the all-seeing Sun, who was the father of King Aeetes, his father-in-law to be, and by his own good fortune, and by his great danger. Immediately, as he was now trusted, he accepted the magic herbs from her, and learnt their use, and returned to the palace, joyfully.

Bk VII:100-158 Jason wins the Golden Fleece

The next day’s dawn dispelled the glittering stars. Then the people gathered on the sacred field of Mars and took up their position on the ridge. The king was seated in the middle, clothed in purple, and distinguished by his ivory sceptre. Behold, the bronze-footed bulls, breathing Vulcan’s fire from nostrils of steel. At the touch of their heat the grass shrivels, and as stoked fires roar, or as broken limestone, that has absorbed the heat inside an earthen furnace, hisses explosively, when cool water is scattered over it, so the flames sounded, pent up in their heaving chests and burning throats. Still the son of Aeson went out to meet them.

As he came to them, the fierce creatures, with their iron-tipped horns, turned their terrible gaze towards him, pawed the dusty ground with their cloven feet, and filled the air with the steam of their bellowing. The Minyans were frozen in fear. He went up to the bulls, not feeling their fiery breath (so great is the power of magic drugs!), and stroking their hanging dewlaps, with a bold hand, yoked them together, and forced them to pull the heavy blade, and till the virgin field with the iron plough. The Colchians were stunned, but the Argonauts increased their shouting, and heightened his courage.

Then he took the dragon’s teeth from the bronze helmet, and scattered them over the turned earth. The soil softened the seeds that had been steeped in virulent poison, and they sprouted, and the teeth, freshly sown, produced new bodies. As an embryo takes on human form in the mother’s womb, and is fully developed there in every aspect, not emerging to the living air until it is complete, so when those shapes of men had been made in the bowels of the pregnant earth, they surged from the teeming soil, and, what is even more wonderful, clashed weapons, created with them. The Pelasgians’ faces fell in fear, and their courage failed them, when they saw these warriors preparing to hurl their sharp spears, at the head of the Haemonian hero. She also, who had rendered him safe, was afraid. When she saw the solitary youth attacked by so many enemies, she grew pale, and sat there, suddenly cold and bloodless. And in case the herbs she had given him had not been potent enough, she chanted a spell to support them, and called on her secret arts.

He threw a boulder into the midst of his enemies, and this turned their attack, on him, against themselves. The earth-born brothers died at each other’s hands, and fell as in civil war. The Achaeans cheered, and clung to the victor, and hugged him in eager embraces. You also, princess among the Barbarians, longed to hold the victorious man: but modesty prevented it. Still, you might have held him, but concern for your reputation stopped you from doing so. What you might fittingly do you did, rejoicing silently, giving thanks, for your incantations, and the gods who inspired them.

The final task was to put the dragon to sleep with the magic drugs. Known for its crest, its triple tongues and curved fangs, it was the dread guardian of the tree’s gold. But when Jason had sprinkled it with the Lethean juice of a certain herb, and three times repeated the words that bring tranquil sleep, that calm the rough seas and turbulent rivers, sleep came to those sleepless eyes, and the heroic son of Aeson gained the Golden Fleece. Proud of his prize, and taking with him a further prize, the one who had helped him gain it, the hero, and his wife Medea, returned to the harbour at Iolchos.

Bk VII:159-178 Jason asks Medea to lengthen Aeson’s life

The elderly Haemonian mothers and fathers bring offerings to mark their sons’ return, and melt incense heaped in the flames. The sacrifice, with gilded horns, that they have dedicated, is led in and killed. But Aeson is absent from the rejoicing, now near death, and weary with the long years. Then Jason, his son, said ‘O my wife, to whom I confess I owe my life, though you have already given me everything, and the total of all your kindnesses is beyond any promises we made, let your incantations, if they can (what indeed can they not do?) reduce my own years and add them to my father’s!’ He could not restrain his tears. Medea was moved by

the loving request, and the contrast with Aeetes, abandoned by her, came to mind. Yet, not allowing herself to be affected by such thoughts, she answered ‘Husband, what dreadful words have escaped your lips? Do you think I can transfer any part of your life to another? Hecate would not allow it: nor is yours a just request. But I will try to grant a greater gift than the one you ask for, Jason. If only the Triple Goddess will aid me, and give her assent in person to this great act of daring, I will attempt to renew your father’s length of years, without need for yours.’

Bk VII:179-233 Medea summons the powers and gathers herbs

Three nights were lacking before the moon’s horns met, to make their complete orb. When it was shining at its fullest, and gazed on the earth, with perfect form, Medea left the palace, dressed in unclasped robes. Her feet were bare, her unbound hair streamed down, over her shoulders, and she wandered, companionless, through midnight’s still silence. Men, beasts, and birds were freed in deep sleep. There were no murmurs in the hedgerows: the still leaves were silent, in silent, dew-filled, air. Only the flickering stars moved. Stretching her arms to them she three times turned herself about, three times sprinkled her head, with water from the running stream, three times let out a wailing cry, then knelt on the hard earth, and prayed:

‘Night, most faithful keeper of our secret rites;

Stars, that, with the golden moon, succeed the fires of light;

Triple Hecate, you who know all our undertakings,

and come, to aid the witches’ art, and all our incantations:

You, Earth, who yield the sorceress herbs of magic force:

You, airs and breezes, pools and hills, and every watercourse;

Be here; all you Gods of Night, and Gods of Groves endorse.

Streams, at will, by banks amazed, turn backwards to their source.

I calm rough seas, and stir the calm by my magic spells:

bring clouds, disperse the clouds, raise storms and storms dispel;

and, with my incantations, I break the serpent’s teeth;

and root up nature’s oaks, and rocks, from their native heath;

and move the forests, and command the mountain tops to shake,

earth to groan, and from their tombs the sleeping dead to wake.

You also, Luna, I draw down, eclipsed, from heaven’s stain,

though bronzes of Temese clash, to take away your pains;

and at my chant, the chariot of the Sun-god, my grandsire,

grows pale: Aurora, at my poisons, dims her morning fire.

You quench the bulls’ hot flame for me: force their necks to bow,

beneath the heavy yoke, that never pulled the curving plough:

You turn the savage warfare, born of the serpent’s teeth,

against itself, and lull the watcher, innocent of sleep;

that guard deceived, bring golden spoil, to the towns of Greece.

Now I need the juice by which old age may be renewed,

that can regain the prime of years, return the flower of youth,

and You will grant it. Not in vain, stars glittered in reply:

not in vain, winged dragons bring my chariot, through the sky.’

There, sent from the sky, was her chariot. When she had mounted, stroked the dragons’ bridled necks, and shaken the light reins in her hands, she was snatched up on high. She looked down on Thessalian Tempe far below, and sent the dragons to certain places that she knew. She considered those herbs that grow on Mount Ossa, those of Mount Pelion, Othrys and Pindus, and higher Olympus, and of those that pleased her, plucked some by the roots, and cut others, with a curved pruning-knife of bronze. Many she chose, as well, from the banks of the Apidanus. Many she chose, as well, from the Amphrysus. Nor did she omit the Enipeus. Peneus, and Spercheus’s waters gave something, and the reedy shores of Boebe. And at Anthedon, by Euboea, she picked a plant of long life, not yet famous for the change it made in Glaucus’s body.

Bk VII:234-293 Medea rejuvenates Aeson

Then she returned, after nine days and nine nights surveying all the lands she had crossed, from her chariot, drawn by the winged dragons. The dragons had only smelt the herbs, yet they shed their skins of many years. Reaching her door and threshold, she stopped on the outside, and under the open sky, avoiding contact with any man, she set up two altars of turf, one on the right to Hecate, one on the left to Youth. She wreathed them with sacred boughs from the wildwood, then dug two trenches near by in the earth, and performed the sacrifice, plunging her knife into the throat of a black-fleeced sheep, and drenching the wide ditches with blood. She poured over it cups of pure honey, and again she poured over it cups of warm milk, uttering words as she did so, calling on the spirits of the earth, and begging the shadowy king and his stolen bride, not to be too quick to steal life from the old man’s limbs.

When she had appeased the gods by prayer and murmured a while, she ordered Aeson’s exhausted body to be carried into the air, and freeing him to deep sleep with her spells, she stretched him out like a corpse on a bed of herbs. She ordered Jason, his son, to go far off, and the attendants to go far off, and warned them to keep profane eyes away from the mysteries. They went as she had ordered. Medea, with streaming hair, circled the burning altars, like a Bacchante, and dipping many-branched torches into the black ditches filled with blood, she lit them, once they were darkened, at the twin altars. Three times with fire, three times with

water, three times with sulphur, she purified the old man.

Meanwhile a potent mixture is heating in a bronze cauldron set on the flames, bubbling, and seething, white with turbulent froth. She boils there, roots dug from a Thessalian valley, seeds, flowerheads, and dark juices. She throws in precious stones searched for in the distant east, and sands that the ebbing tide of ocean washes. She adds hoar-frost collected by night under the moon, the wings and flesh of a vile screech-owl, and the slavering foam of a sacrificed were-wolf, that can change its savage features to those of a man. She does not forget the scaly skin of a thin Cinyphian water-snake, the liver of a long-lived stag, the eggs and the head of a crow that has lived for nine human life-times.

With these, and a thousand other nameless things, the barbarian witch pursued her greater than mortal purpose. She stirred it all with a long-dry branch of a fruitful olive, mixing the depths with the surface. Look! The ancient staff turned in the hot cauldron, first grew green again, then in a short time sprouted leaves, and was, suddenly, heavily loaded with olives. And whenever the flames caused froth to spatter from the hollow bronze, and warm drops to fall on the earth, the soil blossomed, and flowers and soft grasses grew.

As soon as she saw this, Medea unsheathed a knife, and cut the old man’s throat, and letting the old blood out, filled the dry veins with the juice. When Aeson had absorbed it, part through his mouth, and part through the wound, the white of his hair and beard quickly vanished, and a dark colour took its place. At a stroke his leanness went, and his pallor and dullness of mind. The deep hollows were filled with rounded flesh, and his limbs expanded. Aeson marvelled, recalling that this was his self of forty years ago.

Source: Ovid’s Metamorphoses, translated by Anthony S. Kline (https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph.htm)