11 Lab 11. False Memory: Remembering Things that Never Happened

Classroom Demonstration

Introduction

Have you ever confidently recalled the circumstances of an event one way while someone else confidently recalled the same event in a completely different way? If so, at least one of you may have had a false memory. False memories exist when people remember something that never happened, or when events are remembered differently than the actual event (Roediger & McDermott, 1995). Note, however, that false memories are not the same as forgetting–the failure to retrieve information.

Some false memories are fairly innocuous. For example, I have a vivid memory of hitting my first home run in fast pitch softball, while a 2nd year graduate student27. My recollection was that it went out to left-center field, and came in the first inning of a game we eventually won. If I were to find out that it actually happened in the 2nd inning, or that it went out to center field, that wouldn’t change anything. Even if I were to find out that it never really happened, that I had only told that story so often that I believed it to be true, there are no consequences of any importance. My ego would be deflated a little, but the world would remain pretty much as it is.

In other context, though, the occurrence of false memories has particularly serious implications. For example, the cost of false memories in the judicial system might well be the imprisonment of innocent individuals. Loftus (Loftus, 2004), for example, discusses the case of Larry Mayes, who became the 100th individual convicted of a crime based on eyewitness memory to be cleared through DNA evidence. Mayes spent 21 years in jail for a crime he never committed, and for which he always proclaimed his innocence.

Furthermore, the effect of highly suggestive techniques in psychotherapy led to a rash of lawsuits in the 1990s and early 2000s from clients suing their therapists. In many of these cases, allegedly “repressed” memories were recovered through some questionable practices such as age-regression hypnosis. There is little doubt that some emotionally-charged memories are lost over time, but there is considerable doubt as to whether these memories can be reliably recovered. The Scientific Advisory Board of the False Memory Syndrome foundation was sufficiently concerned about these problems that they drafted the following statement:

Because of the continuing misuse of trust, power, and authority in some forms of mental health treatment, and because of our sense of social responsibility to the victims of these treatments, we, the assembled members of the Scientific and Professional Advisory Board of the False Memory Syndrome Foundation, unanimously agree to the following:

1. We endorse the major conclusions of the Working Group on Reported Recovered Memories of Child Sexual Abuse of the Royal College of Psychiatrists that “there is no reliable means of distinguishing a true memory from an illusory one other than by external confirmation. There are, of course, some memories so bizarre or impossible that they are not credible. If something could not happen, it did not happen.” (British Journal of Psychiatry, 1998, 172, p. 304)

2. We also endorse their conclusion that “Evidence does not support the existence of ‘robust repression’.” We would add that because exactly what is meant by the terms “repression” and “dissociation” is far from clear, their use has become idiosyncratic, metaphoric, and arbitrary.

3. Moreover, we find no credible evidence that procedures based on assumptions of the historic accuracy of “recovered memories” of childhood sexual abuse benefit distressed individuals.

4. In contrast, we find increasing evidence that such procedures can severely harm patients and their families.

5. Despite growing awareness of these concerns in public and professional circles, no major United States mental health professional association has acted decisively to prevent its members from contributing to this public health problem.

(False Memory Syndrome Foundation Scientific Advisory Board, 1998)

Little empirical data exists to indicate memories can be repressed or recovered accurately after many years have passed. While no psychologist denies that child abuse is a grave problem, research has clearly shown that memories can be altered and within limits, even created. This lab demonstrates the relative ease with which a false memory can be induced.

In an often-cited study, Loftus and Pickrell (Loftus & Pickrell, 1995) were able to implant false memories of being lost in a shopping mall. Volunteers (older siblings or parents of the subjects) provided several true events that occurred during the subject’s childhood. In addition, they provided information about where the family went shopping and who usually went along on shopping trips. The shopping information was used to construct a plausible false event about the younger sibling or the offspring getting lost in a mall. The volunteers later presented all of the events, including the false event, to their younger sibling, son or daughter. The subjects were asked if they remembered each event. One-quarter of the subjects reported that they remembered the false event! Some critics have suggested that being lost in a shopping mall may be a poor example of a created memory. While the specific event in question may have been contrived, a similar event may have actually happened–perhaps even to you.

Hyman and Pentland (Hyman & Pentland, 1996) improved upon Loftus and Pickrell’s methodology by using a false event that was plausible, but did not happen to any potential subjects–knocking a punch bowl over on the parents of the bride at a wedding when the subject was 5-years-old. Hyman and Pentland, following the same basic procedure of Loftus and Pickrell, obtained true events from the subjects’ parents. However, they added a manipulation similar to techniques often used during therapy: half of the subjects used guided imagery during recall. Guided imagery has been advocated as a valuable memory tool to recover allegedly repressed memories of childhood sexual abuse (Bass & Davis, 1988). In this procedure, subjects are told to imagine how an event may have taken place, or how the surroundings might have looked even though no clear memory exists. Furthermore, Hyman and Pentland asked subjects to recall events at several different times, similar to the repeated sessions often used by therapists in recovered memory therapy. After three interviews, Hyman and Pentland reported that 38% of the subjects in the imagery condition reported remembering the punch bowl incident; without the imagery instructions, only 12% reported remembering the punch bowl incident.

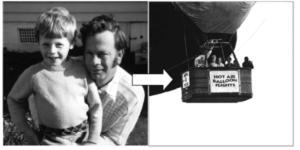

Two recent articles illustrate the powerful effects exerted by retrieval cues (Lindsay, Hagen, Read, Wade, & Garry, 2004; Wade, Garry, Read, & Lindsay, 2002). Wade et al. (2002) created a false photograph of a childhood event. They took an existing photograph of a parent and child riding in a hot air balloon, and digitally inserted the faces of the experimental subjects (as children) and their parents over the existing faces. An example of the photographs created is shown in Figure 4. Half of the individuals shown this false photograph created a complete or partial memory for this fictitious event.

Figure 12-1. An example of a photograph used by Wade et al (2002) to create a false memory of a childhood event.

In a second study, Lindsay et al. (2004) showed subjects true photographs as a way of soliciting childhood memories. In addition to questioning subjects about real event, however, Lindsay et al. asked about a false event (placing “slime” in their teacher’s desk). When subjects were shown class photographs that coincided with this fictitious event, the rate of false memory reports were twice as high as they were when subjects were not shown photographs. Even real photographs can be reconstructed into false memories.

False memories are not limited to life-like events. In fact, one of the most important and influential papers on this topic was performed using simple word lists (Roediger & McDermott, 1995). Roediger and McDermott presented lists of semantically-related words, designed to elicit false recall of a word that was not actually presented. They used 16 lists of words; after the first 8 lists were presented, subjects were asked to recall as many of the words as possible. Then, the next 8 lists were presented, and a recognition test was administered. The experiment was counterbalanced such that half the subjects did the free recall task first, while the other half did the recognition task first. Roediger and McDermott found that the non-presented word was recalled 55% of the time, compared to only 47% of the presented words. Moreover, the non-presented word was recognized 93% of the time. Were subjects less confident when falsely recalling items? No. Roediger and McDermott reported that subjects were just as confident when retrieving false words as they were in retrieving presented words.

There are obvious differences between false memories of being lost in the shopping mall, knocking over a punch bowl, or recalling a word that had never been presented, and recovering memories of childhood sexual abuse. The evidence that memories of events that never occurred can come to be confidently remembered should at the very least inform us of the possibility that false memories of childhood events may also be created. Yet many therapists use techniques to try to uncover memories of childhood sexual abuse that the patient does not remember. In fact, a recent survey found that 25% of therapists reported a constellation of beliefs and practices geared towards memory recovery (Poole, Lindsay, Memon, & Bull, 1995).

For this lab, we’ll be using just 4 of the lists created by Roediger and McDermott.

Questions for Lab 11

1. Based on these data, what percentage of subjects recalled each of the critical lures? How do our results compare to those obtained by Roediger and McDermott (1995)?

2. Use the theory of spreading activation (see Lab 8) to explain the results of this lab.

3. Roediger and McDermott (1995) found that the critical (false) word was most likely to be recalled at the end of the recall task. For example, if 15 of the 30 words were recalled, the non-presented “false” word was most likely to be the 14th or 15th word recalled. Why do you think that happened?

4. Explain the results of Roediger and McDermott (1995) and those obtained in our lab arguing for the reconstructive nature of memory.

5. Considering the research on false memories (Hyman & Pentland, 1996; Loftus & Pickrell, 1995; Roediger & McDermott, 1995), do you think therapists should probe for “repressed memories”? Why or why not?

6. What kind of implications do experiments on false memory have for evaluating the validity of eyewitness accounts?

7. Last time you went to see your doctor, you remembered him/her wearing a stethoscope, but later found out that, because of his/her hearing impairment, your doctor does not use a stethoscope. Why might have you been mistaken?

Results for Lab 11

Record the number of people who recalled each word.

N =

|

List 1 |

# recalled |

|

List 2 |

# recalled |

|

List 3 |

# recalled |

|

List 4 |

# recalled |

|

thread |

|

|

bed |

|

|

nurse |

|

|

butter |

|

|

pin |

|

|

rest |

|

|

sick |

|

|

food |

|

|

eye |

|

|

awake |

|

|

lawyer |

|

|

eat |

|

|

sewing |

|

|

tired |

|

|

medicine |

|

|

sandwich |

|

|

sharp |

|

|

dream |

|

|

health |

|

|

rye |

|

|

point |

|

|

wake |

|

|

hospital |

|

|

jam |

|

|

prick |

|

|

snooze |

|

|

dentist |

|

|

milk |

|

|

thimble |

|

|

blanket |

|

|

physician |

|

|

flour |

|

|

haystack |

|

|

doze |

|

|

ill |

|

|

jelly |

|

|

thorn |

|

|

slumber |

|

|

patient |

|

|

dough |

|

|

hurt |

|

|

snore |

|

|

office |

|

|

crust |

|

|

injection |

|

|

nap |

|

|

stethoscope |

|

|

slice |

|

|

syringe |

|

|

peace |

|

|

surgeon |

|

|

wine |

|

|

cloth |

|

|

yawn |

|

|

clinic |

|

|

loaf |

|

|

knitting. |

|

|

drowsy |

|

|

cure |

|

|

toast |

|

|

needle* |

|

|

sleep* |

|

|

doctor* |

|

|

bread* |

|

*critical word (not presented)

False Memory

Group Data Only

NAME: