3 Lab 3. Stroop Interference: Pay No Attention to the Man Behind the Curtain

CogLab Exercise 13

The Stroop interference task is one of the most familiar—and most intriguing—experiments in the history of cognitive psychology. It is appealing because of its simplicity, and for its ability to consistently trip up subjects performing the test. The most standard version of the Stroop test requires subjects to say aloud the color of ink that a word is printed in. The tricky part is that the words are color words different from the ink they’re printed in. For example, if the word BLUE was written in red ink, subjects would have to say “red” instead of “blue.”

It sounds simple, but when attempting to read a list of such incongruent color words quickly, the task becomes extremely difficult. Understanding what exactly makes the task so challenging has intrigued cognitive psychologists since John Ridley Stroop first introduced the experiment in 1935(Stroop, 1935).

When Stroop designed his experiment, it was a logical yet creative synthesis of all prior research on the concept of interference. Numerous others before him had shown that subjects could read the word “blue” more quickly than they could look at a blue square and say that it was blue. James Cattell, in 1886, claimed that this is because we are trained to read words when we see them, but we are not in the practice of naming the colors of things when we first encounter them. (We’re more likely to think “apple” than “red”). So, the delay in naming the color of a square (compared to reading the word for the color) was explained by our natural tendency to identify the square as a square before we identify its color.

This notion is the essence of one of the primary theories explaining the Stroop effect: automaticity. For any literate person, reading is an automatic process. When we encounter a word, we read it. It’s hard not to read a word, even when we’re asked not to. For example, try not reading the bold words in the next sentence. I bet you weren’t able to ignore the bold words, were you? You had to look at the word to see if it was bold, and by then you had already read it. The same situation is created by the Stroop task. Subjects are asked to ignore the meaning of the word YELLOW and focus only on the color of the ink it is printed in. But, just like with the apple, before they notice the color they notice the word itself. Thus the interference.

Stroop was the first one who came up with the idea of combining the color naming task and the word reading task. Though he is most renowned for this portion of his study, it actually included other experiments. His first experiment sought to discover whether or not interference worked in the opposite direction. That is, if subjects would have trouble reading the word YELLOW when it was printed in blue ink. Both Stroop’s data and subsequent replications show that incongruent colors cause no significant interference on the reading of the words. This supports the automaticity hypothesis.

The other primary theory explaining the Stroop effect is a speed of processing hypothesis, arguing that both the word-reading and color-naming take place simultaneously, but that word naming occurs faster and thus interferes with the color naming. It is assumed that the faster process can interfere with the slower process, but not vice versa.

Both theories have enjoyed rigorous support, and both have been easily refuted. The speed of processing theory is challenged when the words are presented either backwards or upside down (Ex: WOLLEY). As would be expected, it takes considerably longer to read these distorted words. In this case, identifying the word’s color happens faster than reading the word, so the roles are reversed. Despite it taking longer to read the words, the incongruent colors still interfere significantly with reporting the color of the print. Because the slower process was then affecting the faster one, the speed of processing theory had to be reconsidered.

The automaticity theory was challenged by Kahneman and Chajczyk (1983). They determined that the automaticity effect could be “diluted” by including an additional “non-color” word in the stimulus. This had the effect of splitting the subjects’ attention and actually reduced the interference of incongruent colors. They essentially discovered that reading a word was less automatic when the subjects had to choose which of two words to read first. This introduced a sliding scale of automaticity, which is counter-intuitive and challenged the entire theory. How can something be partly automatic? However, because a lessened form of interference still existed, the theory had to be modified rather than dismissed altogether. The modification produced a “continuum of automaticity,” claiming that actions only became automatic with continued practice, and what was automatic could be altered over time. In essence, automatic was redefined as “well-practiced.”

Interestingly, Stroop’s often-overlooked third experiment in his 1935 study addressed this very issue. Stroop was convinced that subjects could overcome the interference effects of the task if they simply practiced focusing on the color of the ink instead of the word itself. He had 32 subjects do just this for eight days, and found that the mean amount of time it took them to name the colors of 50 words dropped from 49.6 seconds to 32.8 seconds. This amount of practice also produced interference on reading the words rather than naming their colors. The mean time jumped from 19.4 seconds to 34.8 seconds after the eight days of training. This was the first report of what is now called the “reverse Stroop effect.” However, this reverse effect disappeared quickly. In a second reading immediately following the first, the time had recovered to a near baseline 22.0 seconds. Overall, Stroop accepted the explanation that our everyday lives leave us more prepared to read words than to analyze their colors.

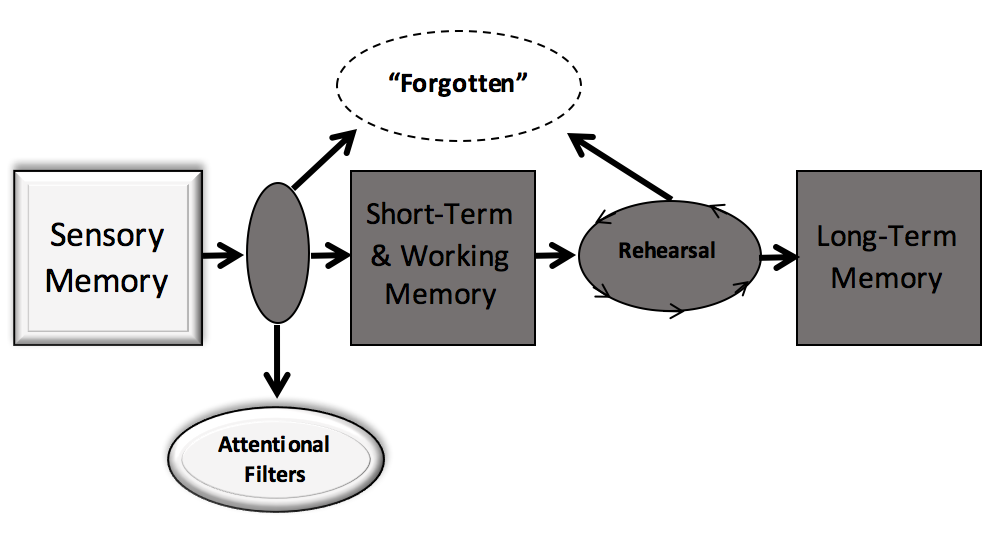

The effect Stroop discovered and publicized is an important one. It is so replicable that it is often included on tests given to assess the extent of mental disorders and learning disabilities. One of the more intriguing frameworks in which the effect has been analyzed is that of working memory. Working memory is a form of short-term memory that allows us to keep bits of information cued up while solving a problem. (Remembering that you’re supposed to focus on the color of ink instead of what the word says is a perfect example). Long and Prat (2002)theorized that subjects with lower working memory capacities would succumb more easily to the interference of the Stroop effect than would subjects with high capacities. They found that their theory was correct, but only when the words presented were consistently incongruent. When congruent words were frequently mixed in (ex: RED printed in red ink), the high capacity subjects performed just as poorly as the low capacity subjects. This shows that the high capacity subjects were actively employing a strategy to complete the task, but that they would only rely on such a strategy when it was obvious that most or all of the words were incongruent.

Long and Prat (2002) wondered if these high capacity subjects were merely ignoring the meaning of the words, or if they were reading them and actively suppressing them. The theory of automaticity suggests they should be unable to look at the words without reading them, and this was indeed the case. Long and Prat found that if the color they were ignoring in one trial was the color they were supposed to name in the next trial, the high capacity subjects struggled. Look at the table below:

|

TRIAL |

STIMULUS |

CORRECT RESPONSE |

|

1 |

BLUE (printed in yellow) |

YELLOW |

|

2 |

RED (printed in blue) |

BLUE |

Because subjects were forced to suppress the word BLUE in trial one, they found it harder to say BLUE in the immediately following trial two. Long and Prat call this phenomenon negative priming. Interestingly, the low-capacity subjects showed considerably less interference as a result of negative priming, presumably because they had less capability to hold the circumstances of the previous trial in their working memory.

As you can imagine, there are numerous explanations of the Stroop effect, depending on which viewpoint one chooses to approach it from. This is why it is still a pertinent and interesting phenomenon to study seventy years after it was first discovered (MacLeod, 1991; MacLeod & Dunbar, 1988). Participants are asked to count how many characters are presented (either 1, 2, 3, or 4). It’s easy when the characters are x’s (i.e. XXX—correct answer: 3), but more challenging when they are digits (i.e. 444—correct answer: 3).

Our lab involves the classical version of the Stroop test with same (congruent) and different (incongruent) colors. Even though you now understand what the Stroop test is about, it will almost certainly still be a challenge.(3)

At this time, complete the experiment stroop effect in CogLab. Instructions can be found in Lab 13 of theCOGLAB Website.

Questions for Lab 3

1. What are the independent and dependent variables in this experiment?

2. Graph both your data and the class data. Did we achieve a Stroop effect? Why or why not? If your results are significantly different from the class data, how would you explain this difference?

3. Is there a speed-accuracy tradeoff in this experiment? In other words, did your accuracy increase as you took more time to make your answers? Why or why not? Is this the expected relationship between speed and accuracy?

4. What if H. M. was a subject in Stroop’s experiment 3, which was designed to see if days and days of practice eliminated the Stroop interference effect? How do you think he would perform compared to the other subjects? (Hint: look back at the information in Lab 1 regarding case studies for some information regarding H.M.’s memory. What type of memory would be involved in the Stroop task? Was that type of memory disrupted in H.M.’s case?)

5. Can you think of a real-world situation where the Stroop effect might take place? How about a reverse Stroop effect? (Just to get you thinking…researchers have documented what is known as an emotional Stroop effect. This happens, for example, when subjects who are deathly afraid of spiders are asked to name the color of ink used to print words such as “crawl,” “venom,” and “web.” It takes them longer to perform the task with these words than with words that are more generally associated with fear, such as “death.” So, can you think of some other possibilities?)

6. According to the theory of automaticity, the Stroop effect occurs because reading familiar words is automatic, making it harder to ignore them when naming ink colors. But what if the words were in a language you barely know? For example, if AZUL appeared in green ink, how would performance differ?

Data Sheet for Lab 3

NAME: ____________________________

Report Mean Reaction Time (ms):

|

Congruent |

Incongruent |

|

|

RT (in ms) |

Graphs for Lab 3

Individual Data

Name: _____________________________

Graphs for Lab 3

Group Data

Name: _____________________________