Ch 1: The Science of Psychology

Clive Wearing is an accomplished musician who lost his ability to form new memories when he became sick at the age of 46. While he can remember how to play the piano perfectly, he cannot remember what he ate for breakfast just an hour ago (Sacks, 2007). James Wannerton experiences a taste sensation that is associated with the sound of words. His former girlfriend’s name tastes like rhubarb (Mundasad, 2013). John Nash is a brilliant mathematician and Nobel Prize winner. However, while he was a professor at MIT, he would tell people that the New York Times contained coded messages from extraterrestrial beings that were intended for him. He also began to hear voices and became suspicious of the people around him. Soon thereafter, Nash was diagnosed with schizophrenia and admitted to a state-run mental institution (O’Connor & Robertson, 2002). Nash was the subject of the 2001 movie A Beautiful Mind. Why did these people have these experiences? How does the human brain work? And what is the connection between the brain’s internal processes and people’s external behaviors? This textbook will introduce you to various ways that the field of psychology has explored these questions.

What is Psychological Science?

Learning Objectives

- Define psychology

- Understand the merits of an education in psychology

What is creativity? What are prejudice and discrimination? What is consciousness? The field of psychology explores questions like these. Psychology refers to the scientific study of the mind and behavior. Psychologists use the scientific method to acquire knowledge. To apply the scientific method, a researcher with a question about how or why something happens will propose a tentative explanation, called a hypothesis, to explain the phenomenon. A hypothesis should fit into the context of a scientific theory, which is a broad explanation or group of explanations for some aspect of the natural world that is consistently supported by evidence over time. A theory is the best understanding we have of that part of the natural world. The researcher then makes observations or carries out an experiment to test the validity of the hypothesis. Those results are then published or presented at research conferences so that others can replicate or build on the results.

Scientists test that which is perceivable and measurable. For example, the hypothesis that a bird sings because it is happy is not a hypothesis that can be tested since we have no way to measure the happiness of a bird. We must ask a different question, perhaps about the brain state of the bird, since this can be measured. However, we can ask individuals about whether they sing because they are happy since they are able to tell us. Thus, psychological science is empirical, based on measurable data.

In general, science deals only with matter and energy, that is, those things that can be measured, and it cannot arrive at knowledge about values and morality. This is one reason why our scientific understanding of the mind is so limited, since thoughts, at least as we experience them, are neither matter nor energy. The scientific method is also a form of empiricism. An empirical method for acquiring knowledge is one based on observation, including experimentation, rather than a method based only on forms of logical argument or previous authorities.

It was not until the late 1800s that psychology became accepted as its own academic discipline. Before this time, the workings of the mind were considered under the auspices of philosophy. Given that any behavior is, at its roots, biological, some areas of psychology take on aspects of a natural science like biology. No biological organism exists in isolation, and our behavior is influenced by our interactions with others. Therefore, psychology is also a social science.

WHY STUDY PSYCHOLOGY?

Often, students take their first psychology course because they are interested in helping others and want to learn more about themselves and why they act the way they do. Sometimes, students take a psychology course because it either satisfies a general education requirement or is required for a program of study such as nursing or pre-med. Many of these students develop such an interest in the area that they go on to declare psychology as their major. As a result, psychology is one of the most popular majors on college campuses across the United States (Johnson & Lubin, 2011). A number of well-known individuals were psychology majors. Just a few famous names on this list are Facebook’s creator Mark Zuckerberg, television personality and political satirist Jon Stewart, actress Natalie Portman, and filmmaker Wes Craven (Halonen, 2011). About 6 percent of all bachelor degrees granted in the United States are in the discipline of psychology (U.S. Department of Education, 2016).

An education in psychology is valuable for a number of reasons. Psychology students hone critical thinking skills and are trained in the use of the scientific method. Critical thinking is the active application of a set of skills to information for the understanding and evaluation of that information. The evaluation of information—assessing its reliability and usefulness— is an important skill in a world full of competing “facts,” many of which are designed to be misleading. For example, critical thinking involves maintaining an attitude of skepticism, recognizing internal biases, making use of logical thinking, asking appropriate questions, and making observations. Psychology students also can develop better communication skills during the course of their undergraduate coursework (American Psychological Association, 2011). Together, these factors increase students’ scientific literacy and prepare students to critically evaluate the various sources of information they encounter.

In addition to these broad-based skills, psychology students come to understand the complex factors that shape one’s behavior. They appreciate the interaction of our biology, our environment, and our experiences in determining who we are and how we will behave. They learn about basic principles that guide how we think and behave, and they come to recognize the tremendous diversity that exists across individuals and across cultural boundaries (American Psychological Association, 2011).

What are the scientific foundations and history of psychological science?

Learning Objectives

- Define structuralism and functionalism and the contributions of Wundt and James to the development of psychology

- Summarize the history of psychology, focusing on the major schools of thought

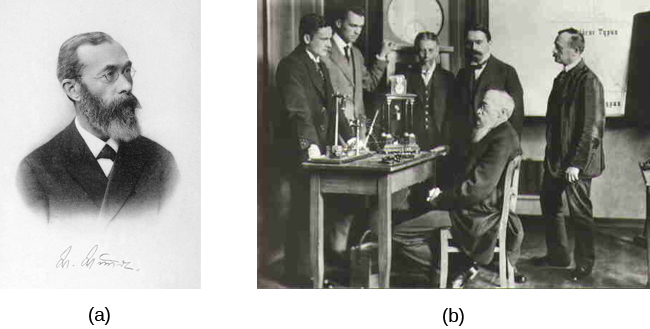

Psychology is a relatively young science with its experimental roots in the 19th century, compared, for example, to human physiology, which dates much earlier. As mentioned, anyone interested in exploring issues related to the mind generally did so in a philosophical context prior to the 19th century. Two men, working in the 19th century, are generally credited as being the founders of psychology as a science and academic discipline that was distinct from philosophy. Their names were Wilhelm Wundt and William James.

Wundt and Structuralism

Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) was a German scientist who was the first person to be referred to as a psychologist. His famous book entitled Principles of Physiological Psychology was published in 1873. Wundt viewed psychology as a scientific study of conscious experience, and he believed that the goal of psychology was to identify components of consciousness and how those components combined to result in our conscious experience. Wundt used introspection (he called it “internal perception”), a process by which someone examines their own conscious experience as objectively as possible, making the human mind like any other aspect of nature that a scientist observed.

Wundt’s version of introspection used only very specific experimental conditions in which an external stimulus was designed to produce a scientifically observable (repeatable) experience of the mind (Danziger, 1980). The first stringent requirement was the use of “trained” or practiced observers, who could immediately observe and report a reaction. The second requirement was the use of repeatable stimuli that always produced the same experience in the subject and allowed the subject to expect and thus be fully attentive to the inner reaction. These experimental requirements were put in place to eliminate “interpretation” in the reporting of internal experiences and to counter the argument that there is no way to know that an individual is observing their mind or consciousness accurately, since it cannot be seen by any other person.

This attempt to understand the structure or characteristics of the mind was known as structuralism. Wundt established his psychology laboratory at the University at Leipzig in 1879. In this laboratory, Wundt and his students conducted experiments on, for example, reaction times. A subject, sometimes in a room isolated from the scientist, would receive a stimulus such as a light, image, or sound. The subject’s reaction to the stimulus would be to push a button, and an apparatus would record the time to reaction. Wundt could measure reaction time to one-thousandth of a second (Nicolas & Ferrand, 1999).

However, despite his efforts to train individuals in the process of introspection, this process remained highly subjective, and there was very little agreement between individuals. As a result, structuralism fell out of favor with the passing of Wundt’s student, Edward Titchener, in 1927 (Gordon, 1995).

Try It

Watch It

Watch this video to learn more about the early history of psychology.

James and Functionalism

William James (1842–1910) was the first American psychologist who espoused a different perspective on how psychology should operate. James was introduced to Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection and accepted it as an explanation of an organism’s characteristics. Key to that theory is the idea that natural selection leads to organisms that are adapted to their environment, including their behavior. Adaptation means that a trait of an organism has a function for the survival and reproduction of the individual, because it has been naturally selected. As James saw it, psychology’s purpose was to study the function of behavior in the world, and as such, his perspective was known as functionalism.

Functionalism focused on how mental activities helped an organism fit into its environment. Functionalism has a second, more subtle meaning in that functionalists were more interested in the operation of the whole mind rather than of its individual parts, which were the focus of structuralism. Like Wundt, James believed that introspection could serve as one means by which someone might study mental activities, but James also relied on more objective measures, including the use of various recording devices, and examinations of concrete products of mental activities and of anatomy and physiology (Gordon, 1995).

| School of Psychology | Description | Historically Important People |

|---|---|---|

| Structuralism | Focused on understanding the conscious experience through introspection | Wilhelm Wundt |

| Functionalism | Emphasized how mental activities helped an organism adapt to its environment | William James |

Multicultural Psychology

Culture has important impacts on individuals and social psychology, yet the effects of culture on psychology are under-studied. There is a risk that psychological theories and data derived from White, American settings could be assumed to apply to individuals and social groups from other cultures and this is unlikely to be true (Betancourt & López, 1993). One weakness in the field of cross-cultural psychology is that in looking for differences in psychological attributes across cultures, there remains a need to go beyond simple descriptive statistics (Betancourt & López, 1993). In this sense, it has remained a descriptive science, rather than one seeking to determine cause and effect. For example, a study of characteristics of individuals seeking treatment for a binge eating disorder in Hispanic American, African American, and Caucasian American individuals found significant differences between groups (Franko et al., 2012). The study concluded that results from studying any one of the groups could not be extended to the other groups, and yet potential causes of the differences were not measured.

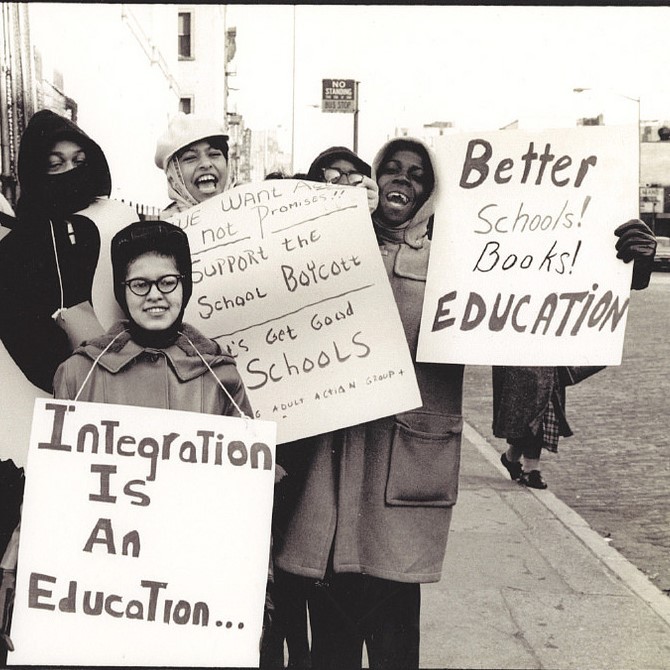

This history of multicultural psychology in the United States is a long one. African American psychologists have played a critical role in researching the cultural differences between African American individual and social psychology . In 1920, Cecil Sumner was the first African American to receive a PhD in psychology in the United States. Sumner established a psychology degree program at Howard University, leading to the education of a new generation of African American psychologists (Black, Spence, and Omari, 2004). Much of the work of early African American psychologists (and a general focus of much work in first half of the 20th century in psychology in the United States) was dedicated to testing and intelligence testing in particular (Black et al., 2004). That emphasis has continued, particularly because of the importance of testing in determining opportunities for children, but other areas of exploration in African-American psychology research include learning style, sense of community and belonging, and spiritualism (Black et al., 2004).

Psychology and Society

Given that psychology deals with the human condition, it is not surprising that psychologists would involve themselves in social issues. For more than a century, psychology and psychologists have been agents of social action and change. Using the methods and tools of science, psychologists have challenged assumptions, stereotypes, and stigma. Founded in 1936, the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues (SPSSI) has supported research and action on a wide range of social issues. Individually, there have been many psychologists whose efforts have promoted social change. Helen Thompson Woolley (1874–1947) and Leta S. Hollingworth (1886–1939) were pioneers in research on the psychology of sex differences. Working in the early 20th century, when women’s rights were marginalized, Thompson examined the assumption that women were overemotional compared to men and found that emotion did not influence women’s decisions any more than it did men’s. Hollingworth found that menstruation did not negatively impact women’s cognitive or motor abilities. Such work combatted harmful stereotypes and showed that psychological research could contribute to social change (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987).

Among the first generation of African American psychologists, Mamie Phipps Clark (1917–1983) and her husband Kenneth Clark (1914–2005) studied the psychology of race and demonstrated the ways in which school segregation negatively impacted the self-esteem of African American children. Their research was influential in the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in the case of Brown v. Board of Education, which ended school segregation (Guthrie, 2003). In psychology, greater advocacy for issues impacting the African American community were advanced by the creation of the Association of Black Psychologists (ABPsi) in 1968.

The American Psychological Association has several ethnically based organizations for professional psychologists that facilitate interactions among members. Since psychologists belonging to specific ethnic groups or cultures have the most interest in studying the psychology of their communities, these organizations provide an opportunity for the growth of research on the impact of culture on individual and social psychology.

Summary of the History of Psychology

Before the time of Wundt and James, questions about the mind were considered by philosophers. However, both Wundt and James helped create psychology as a distinct scientific discipline. Wundt was a structuralist, which meant he believed that our cognitive experience was best understood by breaking that experience into its component parts. He thought this was best accomplished by introspection.

William James was the first American psychologist, and he was a proponent of functionalism. This particular perspective focused on how mental activities served as adaptive responses to an organism’s environment. Like Wundt, James also relied on introspection; however, his research approach also incorporated more objective measures as well.

Sigmund Freud believed that understanding the unconscious mind was absolutely critical to understand conscious behavior. This was especially true for individuals that he saw who suffered from various hysterias and neuroses. Freud relied on dream analysis, slips of the tongue, and free association as means to access the unconscious. Psychoanalytic theory remained a dominant force in clinical psychology for several decades.

Gestalt psychology was very influential in Europe. Gestalt psychology takes a holistic view of an individual and his experiences. As the Nazis came to power in Germany, Wertheimer, Koffka, and Köhler immigrated to the United States. Although they left their laboratories and their research behind, they did introduce America to Gestalt ideas. Some of the principles of Gestalt psychology are still very influential in the study of sensation and perception.

One of the most influential schools of thought within psychology’s history was behaviorism. Behaviorism focused on making psychology an objective science by studying overt behavior and deemphasizing the importance of unobservable mental processes. John Watson is often considered the father of behaviorism, and B. F. Skinner’s contributions to our understanding of principles of operant conditioning cannot be underestimated.

As behaviorism and psychoanalytic theory took hold of so many aspects of psychology, some began to become dissatisfied with psychology’s picture of human nature. Thus, a humanistic movement within psychology began to take hold. Humanism focuses on the potential of all people for good. Both Maslow and Rogers were influential in shaping humanistic psychology.

During the 1950s, the landscape of psychology began to change. A science of behavior began to shift back to its roots of focus on mental processes. The emergence of neuroscience and computer science aided this transition. Ultimately, the cognitive revolution took hold, and people came to realize that cognition was crucial to a true appreciation and understanding of behavior.

| School of Psychology | Description | Earliest Period | Historically Important People |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychodynamic Psychology | Focuses on the role of the unconscious and childhood experiences in affecting conscious behavior. | Very late 19th to Early 20th Century | Sigmund Freud, Erik Erikson |

| Behaviorism | Focuses on observing and controlling behavior through what is observable. Puts an emphasis on learning and conditioning. | Early 20th Century | Ivan Pavlov, John B. Watson, B. F. Skinner |

| Humanistic Psychology | Emphasizes the potential for good that is innate to all humans and rejects that psychology should focus on problems and disorders. | 1950s | Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers |

| Cognitive Psychology | Focuses not just on behavior, but on on mental processes and internal mental states. | 1960s[1] | Ulric Neisser, Noam Chomsky, Jean Piaget, Lev Vygotsky |

Try It

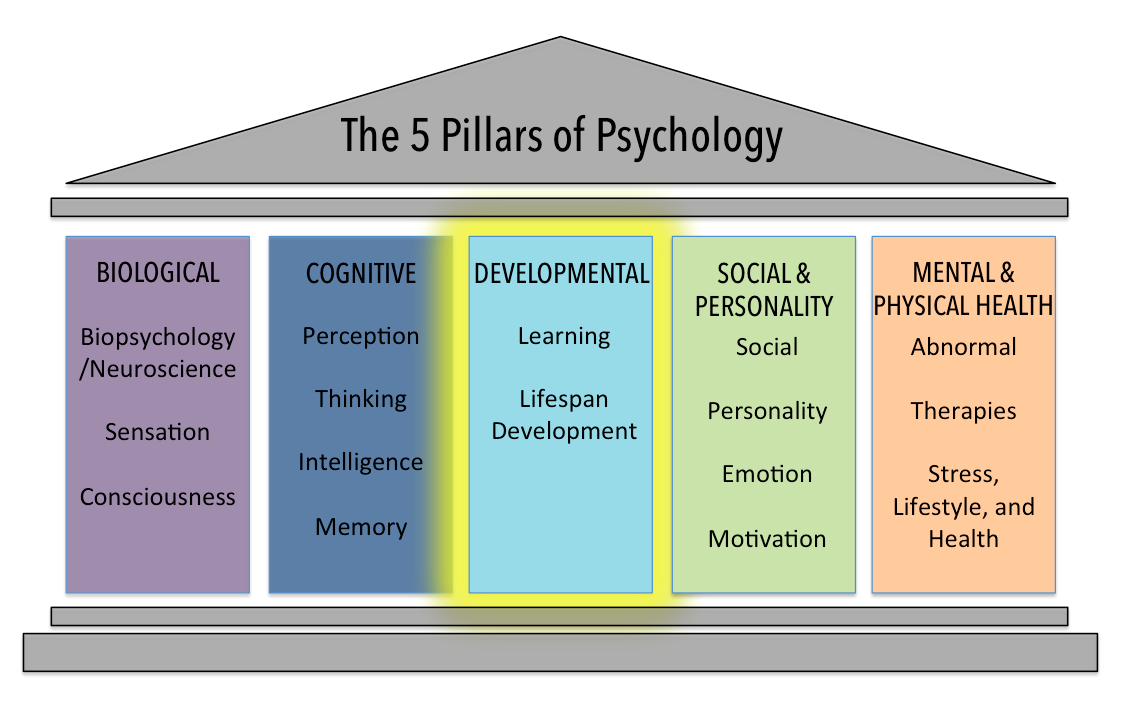

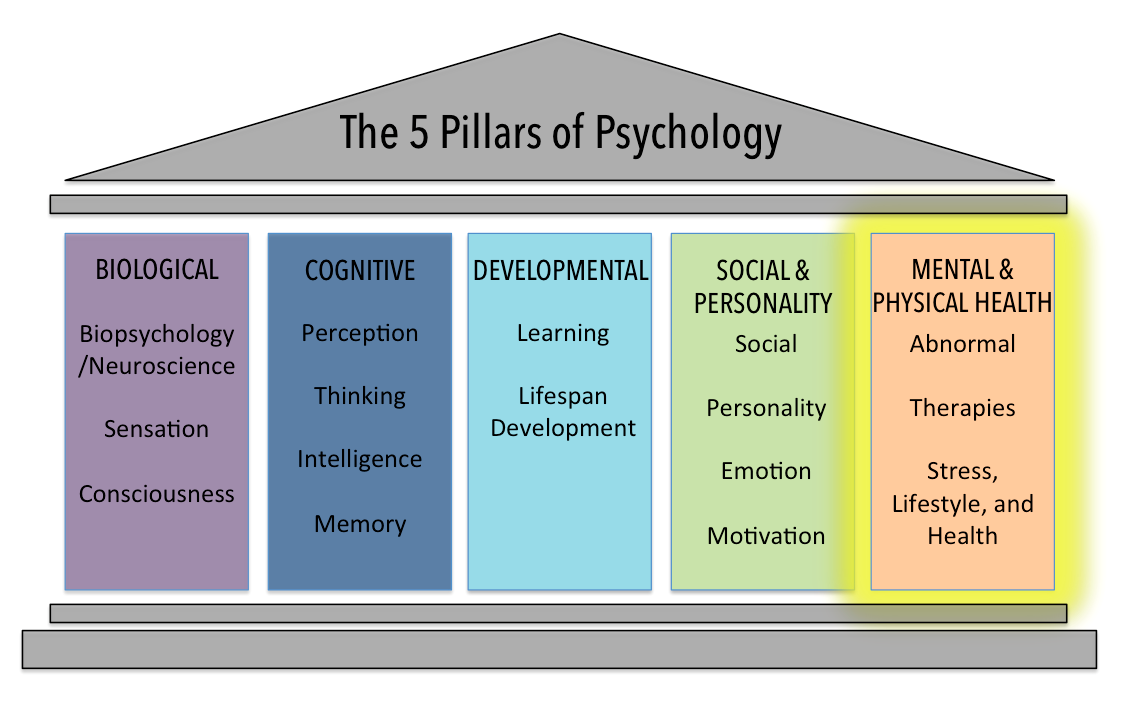

What are the domains (pillars) of contemporary psychology?

Learning Objectives

- List and define the five major domains, or pillars, of contemporary psychology

- Describe the basic interests and applications of biopsychology and evolutionary psychology

- Describe the basic interests and applications of cognitive psychology

- Describe the basic interests and applications of developmental psychology

- Describe the basic interests and applications of social psychology and personality psychology

- Describe the basic interests and applications of abnormal, clinical, and health psychology

Introduction to Contemporary Psychology

Contemporary psychology is a diverse field that is influenced by all of the historical perspectives described in the previous section of reading. Reflective of the discipline’s diversity is the diversity seen within the American Psychological Association (APA). The APA is a professional organization representing psychologists in the United States. The APA is the largest organization of psychologists in the world, and its mission is to advance and disseminate psychological knowledge for the betterment of people. There are 56 divisions within the APA, representing a wide variety of specialties that range from Societies for the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality to Exercise and Sport Psychology to Behavioral Neuroscience and Comparative Psychology. Reflecting the diversity of the field of psychology itself, members, affiliate members, and associate members span the spectrum from students to doctoral-level psychologists and come from a variety of places including educational settings, criminal justice, hospitals, the armed forces, and industry (American Psychological Association, 2014). G. Stanley Hall was the first president of the APA. Before he earned his doctoral degree, he was an adjunct instructor at Wilberforce University, a historically black college/university (HBCU), while serving as faculty at Antioch College. Hall went on to work under William James, earning his PhD. Eventually, he became the first president of Clark University in Massachusetts when it was founded (Pickren & Rutherford, 2010).

The Association for Psychological Science (APS) was founded in 1988 and seeks to advance the scientific orientation of psychology. Its founding resulted from disagreements between members of the scientific and clinical branches of psychology within the APA. The APS publishes five research journals and engages in education and advocacy with funding agencies. A significant proportion of its members are international, although the majority is located in the United States. Other organizations provide networking and collaboration opportunities for professionals of several ethnic or racial groups working in psychology, such as the National Latina/o Psychological Association (NLPA), the Asian American Psychological Association (AAPA), the Association of Black Psychologists (ABPsi), and the Society of Indian Psychologists (SIP). Most of these groups are also dedicated to studying psychological and social issues within their specific communities.

This section will provide an overview of the major subdivisions within psychology today in the order in which they are introduced throughout the remainder of this textbook. This is not meant to be an exhaustive listing, but it will provide insight into the major areas of research and practice of modern-day psychologists.

Link to Learning

Psychologists agree that there is no one right way to study the way people think or behave. There are, however, various schools of thought that evolved throughout the development of psychology that continue to shape the way we investigate human behavior. For example, some psychologists might attribute a certain behavior to biological factors such as genetics while another psychologist might consider early childhood experiences to be a more likely explanation for the behavior. Many expert psychologists focus their entire careers on just one facet of psychology, such as developmental psychology or cognitive psychology, or even more specifically, newborn intelligence or language processing.

While the field of study is large and vast, this text aims to introduce you to the main topics with psychology. You’ll get exposure to the various branches and sub-fields within the discipline and come to understand how they are all interconnected and essential in understanding behavior and mental processes. The five main psychological pillars, or domains, as we will refer to them, are:

- Domain 1: Biological (includes neuroscience, consciousness, and sensation)

- Domain 2: Cognitive (includes the study of perception, cognition, memory, and intelligence)

- Domain 3: Development (includes learning and conditioning, lifespan development, and language)

- Domain 4: Social and Personality (includes the study of personality, emotion, motivation, gender, and culture)

- Domain 5: Mental and Physical Health (includes abnormal psychology, therapy, and health psychology)

These five domains cover the main viewpoints, or perspectives, of psychology. These perspectives emphasize certain assumptions about behavior and provide a framework for psychologists in conducting research and analyzing behavior. They include some you have already read about, including Freud’s psychodynamic perspective, behaviorism, humanism, and the cognitive approach. Other perspectives include the biological perspective, evolutionary, and socio-cultural perspectives.

Digging Deeper: Helpful Hints

A neat way to remember the major perspectives in psychology is to think about your hand and associate each finger with a prominent psychological approach:

- Index Finger: Tap your finger to the temple of your head as if you were thinking about something. This is the cognitive perspective.

- Middle Finger: If you stuck up your middle finger to flip someone off, that would be bad behavior in many cultures. This represents the behavioral perspective, which falls under the developmental domain.

- Ring Finger: This is typically where you would wear a wedding band. For some people this is a healthy lifestyle choice, and for others this is a cause of stress. For some, the thought of marriage causes anxiety, which may lead to therapy. This represents the mental and physical health domain.

- Pinky Finger: This little finger was born this way—short. You can thank your biology for that. This represents the biological perspective.

- Palm of hand: In many cultures, giving a high-five is an acceptable greeting. This represents the social and personality domain

Try It

Biopsychology and Evolutionary Biology

Biopsychology—also known as biological psychology or psychobiology—is the application of the principles of biology to the study of mental processes and behavior. As the name suggests, biopsychology explores how our biology influences our behavior. While biological psychology is a broad field, many biological psychologists want to understand how the structure and function of the nervous system is related to behavior. The fields of behavioral neuroscience, cognitive neuroscience, and neuropsychology are all subfields of biological psychology.

The research interests of biological psychologists span a number of domains, including but not limited to, sensory and motor systems, sleep, drug use and abuse, ingestive behavior, reproductive behavior, neurodevelopment, plasticity of the nervous system, and biological correlates of psychological disorders. Given the broad areas of interest falling under the purview of biological psychology, it will probably come as no surprise that individuals from all sorts of backgrounds are involved in this research, including biologists, medical professionals, physiologists, and chemists. This interdisciplinary approach is often referred to as neuroscience, of which biological psychology is a component (Carlson, 2013).

Evolutionary Psychology

While biopsychology typically focuses on the immediate causes of behavior based in the physiology of a human or other animal, evolutionary psychology seeks to study the ultimate biological causes of behavior. Just as genetic traits have evolved and adapted over time, psychological traits can also evolve and be determined through natural selection. Evolutionary psychologists study the extent that a behavior is impacted by genetics. The study of behavior in the context of evolution has its origins with Charles Darwin, the co-discoverer of the theory of evolution by natural selection. Darwin was well aware that behaviors should be adaptive and wrote books titled, The Descent of Man (1871) and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), to explore this field.

Evolutionary psychology is based on the hypothesis that, just like hearts, lungs, livers, kidneys, and immune systems, cognition has functional structure that has a genetic basis, and therefore has evolved by natural selection. They seek to understand psychological mechanisms by understanding the survival and reproductive functions they might have served over the course of evolutionary history. These might include abilities to infer others’ emotions, discern kin from non-kin, identify and prefer healthier mates, cooperate with others and follow leaders. Consistent with the theory of natural selection, evolutionary psychology sees humans as often in conflict with others, including mates and relatives. For instance, a mother may wish to wean her offspring from breastfeeding earlier than does her infant, which frees up the mother to invest in additional offspring.

Evolutionary psychology, and specifically, the evolutionary psychology of humans, has enjoyed a resurgence in recent decades. To be subject to evolution by natural selection, a behavior must have a significant genetic cause. In general, we expect all human cultures to express a behavior if it is caused genetically, since the genetic differences among human groups are small. The approach taken by most evolutionary psychologists is to predict the outcome of a behavior in a particular situation based on evolutionary theory and then to make observations, or conduct experiments, to determine whether the results match the theory.

There are many areas of human behavior for which evolution can make predictions. Examples include memory, mate choice, relationships between kin, friendship and cooperation, parenting, social organization, and status (Confer et al., 2010).

Try It

Evolutionary psychologists have had success in finding experimental correspondence between observations and expectations. In one example, in a study of mate preference differences between men and women that spanned 37 cultures, Buss (1989) found that women valued earning potential factors greater than men, and men valued potential reproductive factors (youth and attractiveness) greater than women in their prospective mates. In general, the predictions were in line with the predictions of evolution, although there were deviations in some cultures.

Sensation and Perception

Scientists interested in both physiological aspects of sensory systems as well as in the psychological experience of sensory information work within the area of sensation and perception. As such, sensation and perception research is also quite interdisciplinary. Imagine walking between buildings as you move from one class to another. You are inundated with sights, sounds, touch sensations, and smells. You also experience the temperature of the air around you and maintain your balance as you make your way. These are all factors of interest to someone working in the domain of sensation and perception.

Try It

Cognitive Psychology

As mentioned in your previous reading, the cognitive revolution created an impetus for psychologists to focus their attention on better understanding the mind and mental processes that underlie behavior. Thus, cognitive psychology is the area of psychology that focuses on studying cognitions, or thoughts, and their relationship to our experiences and our actions. Like biological psychology, cognitive psychology is broad in its scope and often involves collaborations among people from a diverse range of disciplinary backgrounds. This has led some to coin the term cognitive science to describe the interdisciplinary nature of this area of research (Miller, 2003).

Cognitive psychologists have research interests that span a spectrum of topics, ranging from attention to problem solving to language to memory. The approaches used in studying these topics are equally diverse. The bulk of content coverage on cognitive psychology will be covered in the modules in this text on thinking, intelligence, and memory. But given its diversity, various concepts related to cognitive psychology will be covered in other sections such as lifespan development, social psychology, and therapy.

Try It

Developmental Psychology

Developmental psychology is the scientific study of development across a lifespan. Developmental psychologists are interested in processes related to physical maturation. However, their focus is not limited to the physical changes associated with aging, as they also focus on changes in cognitive skills, moral reasoning, social behavior, and other psychological attributes. Early developmental psychologists focused primarily on changes that occurred through reaching adulthood, providing enormous insight into the differences in physical, cognitive, and social capacities that exist between very young children and adults. For instance, research by Jean Piaget demonstrated that very young children do not demonstrate object permanence. Object permanence refers to the understanding that physical things continue to exist, even if they are hidden from us.

If you were to show an adult a toy, and then hide it behind a curtain, the adult knows that the toy still exists. However, very young infants act as if a hidden object no longer exists. The age at which object permanence is achieved is somewhat controversial (Munakata, McClelland, Johnson, and Siegler, 1997).

Behavioral Psychology

Another critical field of study under the development domain is that of learning and behaviorism, which you read about already. The primary developments in learning and conditioning came from the work of Ivan Pavlov, John B. Watson, Edward Lee Thorndike, and B. F. Skinner. Contemporary behaviorists apply learning techniques in the form of behavior modification for a variety of mental problems. Learning is seen as behavior change molded by experience; it is accomplished largely through either classical or operant conditioning.

Try It

Social Psychology

Social psychology is the scientific study of how people’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by the actual, imagined, or implied presence of others. This domain of psychology is concerned with the way such feelings, thoughts, beliefs, intentions, and goals are constructed, and how these psychological factors, in turn, influence our interactions with others.

Social psychology typically explains human behavior as a result of the interaction of mental states and immediate social situations. Social psychologists, therefore, examine the factors that lead us to behave in a given way in the presence of others, as well as the conditions under which certain behaviors, actions, and feelings occur. They focus on how people construe or interpret situations and how these interpretations influence their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Ross & Nisbett, 1991). Thus, social psychology studies individuals in a social context and how situational variables interact to influence behavior.

Some social psychologists study large-scale sociocultural forces within cultures and societies that affect the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of individuals. These include forces such as attitudes, child-rearing practices, discrimination and prejudice, ethnic and racial identity, gender roles and norms, family and kinship structures, power dynamics, regional differences, religious beliefs and practices, rituals, and taboos. Several subfields within psychology seek to examine these sociocultural factors that influence human mental states and behavior; among these are social psychology, cultural psychology, cultural-historical psychology, and cross-cultural psychology.

There are many interesting examples of social psychological research, and you will read about many of these later in this course. Until then, you will be introduced to one of the most controversial psychological studies ever conducted. Stanley Milgram was an American social psychologist who is most famous for research that he conducted on obedience. After the Holocaust, in 1961, a Nazi war criminal, Adolf Eichmann, who was accused of committing mass atrocities, was put on trial. Many people wondered how German soldiers were capable of torturing prisoners in concentration camps, and they were unsatisfied with the excuses given by soldiers that they were simply following orders. At the time, most psychologists agreed that few people would be willing to inflict such extraordinary pain and suffering, simply because they were obeying orders. Milgram decided to conduct research to determine whether or not this was true.

As you will read later in the text, Milgram found that nearly two-thirds of his participants were willing to deliver what they believed to be lethal shocks to another person, simply because they were instructed to do so by an authority figure (in this case, a man dressed in a lab coat). This was in spite of the fact that participants received payment for simply showing up for the research study and could have chosen not to inflict pain or more serious consequences on another person by withdrawing from the study. No one was actually hurt or harmed in any way, Milgram’s experiment was a clever ruse that took advantage of research confederates, those who pretend to be participants in a research study who are actually working for the researcher and have clear, specific directions on how to behave during the research study (Hock, 2009). Milgram’s and others’ studies that involved deception and potential emotional harm to study participants catalyzed the development of ethical guidelines for conducting psychological research that discourage the use of deception of research subjects, unless it can be argued not to cause harm and, in general, requiring informed consent of participants.

Personality Psychology

Another major field of study within the social and personality domain is, of course, personality psychology. Personality refers to the long-standing traits and patterns that propel individuals to consistently think, feel, and behave in specific ways. Our personality is what makes us unique individuals. Each person has an idiosyncratic pattern of enduring, long-term characteristics, and a manner in which they interact with other individuals and the world around them. Our personalities are thought to be long-term, stable, and not easily changed. Personality psychology focuses on

- construction of a coherent picture of the individual and their major psychological processes.

- investigation of individual psychological differences.

- investigation of human nature and psychological similarities between individuals.

Several individuals (e.g., Freud and Maslow) that we have already discussed in our historical overview of psychology, and the American psychologist Gordon Allport, contributed to early theories of personality. These early theorists attempted to explain how an individual’s personality develops from his or her given perspective. For example, Freud proposed that personality arose as conflicts between the conscious and unconscious parts of the mind were carried out over the lifespan. Specifically, Freud theorized that an individual went through various psychosexual stages of development. According to Freud, adult personality would result from the resolution of various conflicts that centered on the migration of erogenous (or sexual pleasure-producing) zones from the oral (mouth) to the anus to the phallus to the genitals. Like many of Freud’s theories, this particular idea was controversial and did not lend itself to experimental tests (Person, 1980).

More recently, the study of personality has taken on a more quantitative approach. Rather than explaining how personality arises, research is focused on identifying personality traits, measuring these traits, and determining how these traits interact in a particular context to determine how a person will behave in any given situation. Personality traits are relatively consistent patterns of thought and behavior, and many have proposed that five trait dimensions are sufficient to capture the variations in personality seen across individuals. These five dimensions are known as the “Big Five” or the Five Factor model, and include dimensions of conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness, and extraversion (shown below). Each of these traits has been demonstrated to be relatively stable over the lifespan (e.g., Rantanen, Metsäpelto, Feldt, Pulkinnen, and Kokko, 2007; Soldz & Vaillant, 1999; McCrae & Costa, 2008) and is influenced by genetics (e.g., Jang, Livesly, and Vernon, 1996).

Try It

Abnormal Psychology

This domain of psychology is what many people think of when they think about psychology—mental disorders and counseling. This includes the study of abnormal psychology, with its focus on abnormal thoughts and behaviors, as well as counseling and treatment methods, and recommendations for coping with stress and living a healthy life.

The names and classifications of mental disorders are listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The DSM is currently in its 5th edition (DSM-V) and has been designed for use in a wide variety of contexts and across clinical settings (including inpatient, outpatient, partial hospital, clinic, private practice, and primary care). The diagnostic manual includes a total of 237 specific diagnosable disorders, each described in detail, including its symptoms, prevalence, risk factors, and comorbidity. Over time, the number of diagnosable conditions listed in the DSM has grown steadily, prompting criticism from some. Nevertheless, the diagnostic criteria in the DSM are more explicit than those of any other system, which makes the DSM system highly desirable for both clinical diagnosis and research.

Clinical Psychology

By far, this is the area of psychology that receives the most attention in popular media, and many people mistakenly assume that all psychology is clinical psychology.

Health Psychology

Health psychology focuses on how health is affected by the interaction of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors. This particular approach is known as the biopsychosocial model. Health psychologists are interested in helping individuals achieve better health through public policy, education, intervention, and research. Health psychologists might conduct research that explores the relationship between one’s genetic makeup, patterns of behavior, relationships, psychological stress, and health. They may research effective ways to motivate people to address patterns of behavior that contribute to poorer health (MacDonald, 2013).

Try It

Learning Objectives

- Describe educational requirements and career options for the study of psychology

Psychologists can work in many different places doing many different things. In general, anyone wishing to continue a career in psychology at a 4-year institution of higher education will have to earn a doctoral degree in psychology for some specialties and at least a master’s degree for others. In most areas of psychology, this means earning a PhD in a relevant area of psychology. Literally, PhD refers to a doctor of philosophy degree, but here, philosophy does not refer to the field of philosophy per se. Rather, philosophy in this context refers to many different disciplinary perspectives that would be housed in a traditional college of liberal arts and sciences.

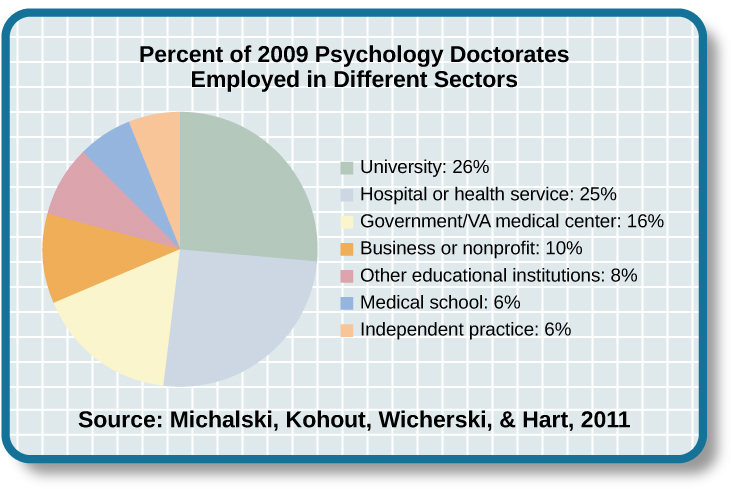

The requirements to earn a PhD vary from country to country and even from school to school, but usually, individuals earning this degree must complete a dissertation. A dissertation is essentially a long research paper or bundled published articles describing research that was conducted as a part of the candidate’s doctoral training. In the United States, a dissertation generally has to be defended before a committee of expert reviewers before the degree is conferred. Once someone earns her PhD, she may seek a faculty appointment at a college or university. Being on the faculty of a college or university often involves dividing time between teaching, research, and service to the institution and profession. The amount of time spent on each of these primary responsibilities varies dramatically from school to school, and it is not uncommon for faculty to move from place to place in search of the best personal fit among various academic environments. The previous section detailed some of the major areas that are commonly represented in psychology departments around the country; thus, depending on the training received, an individual could be anything from a biological psychologist to a clinical psychologist in an academic setting.

Other Careers in Academic Settings

Often times, schools offer more courses in psychology than their full-time faculty can teach. In these cases, it is not uncommon to bring in an adjunct faculty member or instructor. Adjunct faculty members and instructors usually have an advanced degree in psychology, but they often have primary careers outside of academia and serve in this role as a secondary job. Alternatively, they may not hold the doctoral degree required by most 4-year institutions and use these opportunities to gain experience in teaching. Furthermore, many 2-year colleges and schools need faculty to teach their courses in psychology. In general, many of the people who pursue careers at these institutions have master’s degrees in psychology, although some PhDs make careers at these institutions as well.

Some people earning PhDs may enjoy research in an academic setting. However, they may not be interested in teaching. These individuals might take on faculty positions that are exclusively devoted to conducting research. This type of position would be more likely an option at large, research-focused universities.

In some areas in psychology, it is common for individuals who have recently earned their PhD to seek out positions in postdoctoral training programs that are available before going on to serve as faculty. In most cases, young scientists will complete one or two postdoctoral programs before applying for a full-time faculty position. Postdoctoral training programs allow young scientists to further develop their research programs and broaden their research skills under the supervision of other professionals in the field.

Career Options Outside of Academics

Individuals who wish to become practicing clinical psychologists have another option for earning a doctoral degree, which is known as a PsyD. A PsyD is a doctor of psychology degree that is increasingly popular among individuals interested in pursuing careers in clinical psychology. PsyD programs generally place less emphasis on research-oriented skills and focus more on application of psychological principles in the clinical context (Norcorss & Castle, 2002).

Regardless of whether earning a PhD or PsyD, in most states, an individual wishing to practice as a licensed clinical or counseling psychologist may complete postdoctoral work under the supervision of a licensed psychologist. Within the last few years, however, several states have begun to remove this requirement, which would allow someone to get an earlier start in his career (Munsey, 2009). After an individual has met the state requirements, his credentials are evaluated to determine whether he can sit for the licensure exam. Only individuals that pass this exam can call themselves licensed clinical or counseling psychologists (Norcross, n.d.). Licensed clinical or counseling psychologists can then work in a number of settings, ranging from private clinical practice to hospital settings. It should be noted that clinical psychologists and psychiatrists do different things and receive different types of education. While both can conduct therapy and counseling, clinical psychologists have a PhD or a PsyD, whereas psychiatrists have a doctor of medicine degree (MD). As such, licensed clinical psychologists can administer and interpret psychological tests, while psychiatrists can prescribe medications.

Individuals earning a PhD can work in a variety of settings, depending on their areas of specialization. For example, someone trained as a biopsychologist might work in a pharmaceutical company to help test the efficacy of a new drug. Someone with a clinical background might become a forensic psychologist and work within the legal system to make recommendations during criminal trials and parole hearings, or serve as an expert in a court case.

While earning a doctoral degree in psychology is a lengthy process, usually taking between 5–6 years of graduate study (DeAngelis, 2010), there are a number of careers that can be attained with a master’s degree in psychology. People who wish to provide psychotherapy can become licensed to serve as various types of professional counselors (Hoffman, 2012). Relevant master’s degrees are also sufficient for individuals seeking careers as school psychologists (National Association of School Psychologists, n.d.), in some capacities related to sport psychology (American Psychological Association, 2014), or as consultants in various industrial settings (Landers, 2011, June 14). Undergraduate coursework in psychology may be applicable to other careers such as psychiatric social work or psychiatric nursing, where assessments and therapy may be a part of the job.

As mentioned in the opening section of this chapter, an undergraduate education in psychology is associated with a knowledge base and skill set that many employers find quite attractive. It should come as no surprise, then, that individuals earning bachelor’s degrees in psychology find themselves in a number of different careers, as shown in the table. Examples of a few such careers can involve serving as case managers, working in sales, working in human resource departments, and teaching in high schools. The rapidly growing realm of healthcare professions is another field in which an education in psychology is helpful and sometimes required. For example, the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) exam that people must take to be admitted to medical school now includes a section on the psychological foundations of behavior.

| Ranking | Occupation |

|---|---|

| 1 | Mid- and top-level management (executive, administrator) |

| 2 | Sales |

| 3 | Social work |

| 4 | Other management positions |

| 5 | Human resources (personnel, training) |

| 6 | Other administrative positions |

| 7 | Insurance, real estate, business |

| 8 | Marketing and sales |

| 9 | Healthcare (nurse, pharmacist, therapist) |

| 10 | Finance (accountant, auditor) |

Link to Learning

Visit this career website describing some of the career options available to people earning bachelor’s degrees in psychology.

Try It

Think It Over

Which of the career options described in this section is most appealing to you?

Watch It

Watch this video from The Psych Show about the benefits and value of studying psychology.

Try It

Think it Over

Putting it together: Foundations of Psychological Science

In this chapter, you learned to

- describe the evolution of psychology and the major pioneers in the field

- identify the various approaches, fields, and subfields of psychology along with their major concepts and important figures

- describe the value of psychology and possible careers paths for those who study psychology

Psychology is a rapidly growing and ever-evolving field of study. In this chapter, you learned the development of psychology as a distinct field of study in the late 1800s. In modern psychology, researchers and practitioners consider some of these historical approaches but also approach the study of mind and behavior through a variety of lenses, including biological, cognitive, developmental, social, and health perspectives.

Watch It

Watch the following Crash Course Psychology video for a good recap of the topics covered in this chapter:

You can view the transcript for “Intro to Psychology: Crash Course Psychology #1” here (opens in new window).

Consider a fascinating example of psychological research conducted by is an Assistant Professor of Cognitive Psychology at Oberlin College, Paul Thibodeau. His focus is on language, specifically how people utilize metaphors and analogies, but he did one study on word aversion that he explains in his own words in the following example. As you read it, consider the breadth of coverage that psychologists cover as well as the importance of the scientific method and research to the investigative process. We’ll learn more about experiments and psychological research in the next module, but if you could design a psychological study based on the topics that piqued your interested in this text so far, what would it be? Where do your interests lie? Remember, there are nearly endless possibilities for research within the vast field of psychology, and studying the subject will serve to your advantage, no matter your chosen field or career path.

Digging Deeper: Word Aversion

If you had to pick the most cringeworthy word in the English language, what would you choose? Many people report that they find words like “moist,” “crevice,” “slacks,” and “luggage” acutely aversive, so maybe you’d pick one of those. For instance, People Magazine recently coined “moist” the “most cringeworthy word” in American English and invited their “sexiest men alive” to try to make it sound “hot” (watch the moist video here).

One writer, in response, described the video as “…pure sadism. It’s torture, it’s rude, and it’s awful…” and claimed that the only way to overcome the experience was to “go Oedipal and gouge your eyes out”. Indeed, readers who find the word “moist” aversive may experience some unpleasantness in reading this paper.

Researcher Paul H. Thibodeau sought to understand how prevalent the aversion to the word “moist” really is, and what makes it so unappealing. He conducted five experiments with over 2,500 participants, and found that about 18% of participants found the word to be aversive. He first hypothesized why people might find the word aversive—is it the sound? Or the connotation and meaning? Or is it due to social expectations and social transmission?

The experiments shows that aversion was most likely due to both social causes and its connotation, as it may be associated with bodily functions. The study found that people who scored highest on their levels of digust toward bodily functions also scored high on their dislike for the word moist. The same people found words like vomit and pleghm to be aversive, but were less affected by similar-sounding words (“hoist”) or by words related to sex.

Often when people were asked to describe why they felt aversion toward the word, they mentioned that they didn’t like the way it sounded. The data reveal, however, that people are not averse to phonetically similar words. Interestingly, other people guessed that people felt an aversion to moist because of its association with sex, but the data also reveal that the word’s connection to sex is not what makes it cringeworthy. It’s important to point out here that one reason research is so valuable is that it contradicts common sense notions and helps us better understand human behavior.

Another piece of evidence supporting the social transmission of the word aversion is that in the study, some participants first watched the People Magazine video of celebrities saying “moist,” while others watched a control video. Those who watched the video found the word more aversive, and negative than those who did not. Dr. Thibodeau summarizes lessons learned from the study as follows:[2]

There are a few important lessons to be learned from these studies. Two are fairly obvious: we now have a better sense of what makes the word “moist” aversive and another demonstration that we’re not particularly good at reflecting accurately on why we think what we think.

More relevant to broader theories in psychology, the work has implications for theories of language processing and the psychology of disgust. Emotional language is processed differently than “neutral” language: it grabs our attention, engages different parts of the brain, and is more likely to be remembered. This can be good or bad: cake mixes that advertise themselves as “moist” may make some people more likely to buy them because they catch our eye, but they may make us less likely to buy them because of the word’s association with disgusting bodily function (an open question).

Disgust is adaptive. If we didn’t have an instinct to run away from vomit and diarrhea, disease would spread more easily. But is this instinct biological or do we learn it? Does our culture shape what we find disgusting? This is a complex and nuanced question. Significant work is needed to answer it definitively. But the present studies suggest that, when it comes to the disgust that is elicited by words like “moist,” there is an important cultural component—the symbols we use to communicate with one another can become contaminated and elicit disgust by virtue of their association with bodily functions.

References (Click to expand)

- American Psychological Association. (2014). Retrieved from www.apa.org

- American Psychological Association. (2014). Graduate training and career possibilities in exercise and sport psychology. Retrieved from http://www.apadivisions.org/division-47/about/resources/training.aspx?item=1

- American Psychological Association. (2011). Psychology as a career. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/education/undergrad/psych-career.aspx

- Betancourt, H., & López, S. R. (1993). The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. American Psychologist, 48, 629–637.

- Black, S. R., Spence, S. A., & Omari, S. R. (2004). Contributions of African Americans to the field of psychology. Journal of Black Studies, 35, 40–64.

- Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12, 1–49.

- Carlson, N. R. (2013). Physiology of Behavior (11th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Confer, J. C., Easton, J. A., Fleischman, D. S., Goetz, C. D., Lewis, D. M. G., Perilloux, C., & Buss, D. M. (2010). Evolutionary psychology. Controversies, questions, prospects, and limitations. American Psychologist, 65, 100–126.

- Danziger, K. (1980). The history of introspection reconsidered. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 16, 241–262.

- Darwin, C. (1871). Thedescent of man and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murray.

- Darwin, C. (1872). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London: John Murray.

- DeAngelis, T. (2010). Fear not. gradPSYCH Magazine, 8, 38.

- Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Projected future growth of the older population. Retrieved from http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/future_growth/future_growth.aspx#age

- Franko, D. L., et al. (2012). Racial/ethnic differences in adults in randomized clinical trials of binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 186–195.

- Friedman, H. (2008), Humanistic and positive psychology: The methodological and epistemological divide. The Humanistic Psychologist, 36, 113–126.

- Gordon, O. E. (1995). A brief history of psychology. Retrieved from http://www.psych.utah.edu/gordon/Classes/Psy4905Docs/PsychHistory/index.html#maptop

- Greengrass, M. (2004). 100 years of B.F. Skinner. Monitor on Psychology, 35, 80.

- Guthrie, R. V. (2003). Even the rat was white: A historical view of psychology (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Halonen, J. S. (2011). White paper: Are there too many psychology majors? Prepared for the Staff of the State University System of Florida Board of Governors. Retrieved from http://www.cogdop.org/page_attachments/0000/0200/FLA_White_Paper_for_cogop_posting.pdf

- Hoffman, C. (2012). Careers in clinical, counseling, or school psychology; mental health counseling; clinical social work; marriage & family therapy and related professions. http://www.indiana.edu/~psyugrad/advising/docs/Careers%20in%20Mental%20Health%20Counseling.pdf

- Hock, R. R. (2009). Social psychology. Forty studies that changed psychology: Explorations into the history of psychological research (pp. 308–317). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

- Jang, K. L., Livesly, W. J., & Vernon, P. A. (1996). Heritability of the Big Five personality dimensions and their facets: A twin study. Journal of Personality, 64, 577–591.

- Johnson, R., & Lubin, G. (2011). College exposed: What majors are most popular, highest paying and most likely to get you a job. Business Insider.com. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/best-college-majors-highest-income-most-employed-georgetwon-study-2011-6?op=1

- Landers, R. N. (2011, June 14). Grad school: Should I get a PhD or Master’s in I/O psychology? http://neoacademic.com/2011/06/14/grad-school-should-i-get-a-ph-d-or-masters-in-io-psychology/#.UuKKLftOnGg

- Macdonald, C. (2013). Health psychology center presents: What is health psychology? Retrieved from http://healthpsychology.org/what-is-health-psychology/

- McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. (2008). Empirical and theoretical status of the five-factor model of personality traits. In G. J. Boyle, G. Matthews, & D. H. Saklofske (Eds.), The Sage handbook of personality theory and assessment. Vol. 1 Personality theories and models. London: Sage.

- Miller, G. A. (2003). The cognitive revolution: A historical perspective. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7, 141–144.

- Munakata, Y., McClelland, J. L., Johnson, M. H., & Siegler, R. S. (1997). Rethinking infant knowledge: Toward an adaptive process account of successes and failures in object permanence tasks. Psychological Review, 104, 689–713.

- Mundasad, S. (2013). Word-taste synaesthesia: Tasting names, places, and Anne Boleyn. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-21060207

- Munsey, C. (2009). More states forgo a postdoc requirement. Monitor on Psychology, 40, 10.

- National Association of School Psychologists. (n.d.). Becoming a nationally certified school psychologist (NCSP). http://www.nasponline.org/CERTIFICATION/becomeNCSP.aspx

- Nicolas, S., & Ferrand, L. (1999). Wundt’s laboratory at Leipzig in 1891. History of Psychology, 2, 194–203.

- Norcross, J. C. (n.d.) Clinical versus counseling psychology: What’s the diff? http://www.csun.edu/~hcpsy002/Clinical%20Versus%20Counseling%20Psychology.pdf

- O’Connor, J. J., & Robertson, E. F. (2002). John Forbes Nash. Retrieved from http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Biographies/Nash.html

- O’Hara, M. (n.d.). Historic review of humanistic psychology. Retrieved from http://www.ahpweb.org/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&layout=item&id=14&Itemid=24

- Person, E. S. (1980). Sexuality as the mainstay of identity: Psychoanalytic perspectives. Signs, 5, 605–630.

- Pickren, W. & Rutherford, A. (2010). A history of modern psychology in context. Wiley.

- Rantanen, J., Metsäpelto, R. L., Feldt, T., Pulkkinen, L., & Kokko, K. (2007). Long-term stability in the Big Five personality traits in adulthood. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 48, 511–518.

- Ross, L., & Nisbett, R. E. (1991). The person and the situation: Perspectives of social psychology. McGraw-Hill.

- Sacks, O. (2007). A neurologists notebook: The abyss, music and amnesia. The New Yorker. Retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2007/09/24/070924fa_fact_sacks?currentPage=all

- Soldz, S., & Vaillant, G. E. (1999). The Big Five personality traits and the life course: A 45-year longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality, 33, 208–232.

- Thorne, B. M., & Henley, T. B. (2005). Connections in the history and systems of psychology (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Tolman, E. C. (1938). The determiners of behavior at a choice point. Psychological Review, 45, 1–41.

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2013). Digest of Education Statistics, 2012 (NCES 2014-015).

Licenses and Attributions (Click to expand)

CC licensed content, Original

- The Science of Psychology. Provided by: Karenna Malavanti. License: CC BY NC SA: Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Introduction to Psychology. Provided by: OpenStax College. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Why It Matters: Psychological Foundations. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution Located at: https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/lumenpsychology/chapter/introduction-16/

- Early Psychology—Structuralism and Functionalism Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution Located at: https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/lumenpsychology/chapter/reading-structuralism-and-functionalism/

- The History of Psychology—The Cognitive Revolution and Multicultural Psychology Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike Located at: https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/lumenpsychology/chapter/reading-the-cognitive-revolution-and-multicultural-psychology/

- History of Psychology. Authored by: Baker, D. B. & Sperry, H. License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License Located at: http://noba.to/j8xkgcz5

- The Five Psychological Domains Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution ShareAlike Located at: https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/lumenpsychology/chapter/psychological-perspectives/

- Theoretical Perspectives in Modern Psychology . Provided by: Boundless. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike Located at: https://www.boundless.com/psychology/textbooks/boundless-psychology-textbook/introduction-to-psychology-1/theoretical-perspectives-in-modern-psychology-23/biopsychology-117-12654/.

- The Biological Domain Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution ShareAlike Located at: https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/lumenpsychology/chapter/reading-biopsychology-and-evolutionary-psychology/

- Biopsychology information. Provided by: Boundless. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-psychology/.

- Evolutionary psychology. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolutionary_psychology.

- The Cognitive Domain Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution Located at: https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/lumenpsychology/chapter/reading-the-cognitive-pillar/

- Cognitive Psychology. Provided by: Boundless. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike Located at: https://www.boundless.com/psychology/textbooks/boundless-psychology-textbook/introduction-to-psychology-1/theoretical-perspectives-in-modern-psychology-23/cognitive-psychology-115-12652/.

- Picture of chimpanze. Authored by: DigitalDesigner. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved Located at: https://pixabay.com/en/isolated-thinking-freedom-ape-1052504/.

- Early Schools of Psychology: Still Active and Advanced Beyond Early Ideas Table. Provided by: Open Learning Initiative. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Located at: https://oli.cmu.edu/jcourse/workbook/activity/page?context=4c39410080020ca60127b04635de0b80. Project: Introduction to Psychology.

- The Developmental Domain Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution ShareAlike Located at: https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/lumenpsychology/chapter/reading-developmental-psychology/

- Behaviorism content. Provided by: Boundless.

- License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike Located at: https://www.boundless.com/psychology/textbooks/boundless-psychology-textbook/introduction-to-psychology-1/theoretical-perspectives-in-modern-psychology-23/behavioral-psychology-113-12650/.

- The Social and Personality Psychology Domain Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution ShareAlike Located at: https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/lumenpsychology/chapter/reading-social-psychology/

- The Mental and Physical Health Domain Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution Located at: https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/lumenpsychology/chapter/reading-mental-and-physical-health-pillar/

- Abnormal Psychology. Provided by: Boundless. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike Located at: https://www.boundless.com/psychology/textbooks/boundless-psychology-textbook/introduction-to-psychology-1/theoretical-perspectives-in-modern-psychology-23/abnormal-psychology-512-16738/.

- Careers in Psychology. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-4-careers-in-psychology. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Merits of an Education in Psychology Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution Located at: https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/lumenpsychology/chapter/merits-of-an-education-in-psychology/

- Putting It Together: Psychological Foundations Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike Located at: https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/lumenpsychology/chapter/putting-it-together-psychological-foundations/

- The Moist Conundrum. Authored by: Paul Thibodeau. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Located at: http://thepsychreport.com/science/moist-conundrum/. Project: The Psych Report.

- A Moist Crevice for Word Aversion: In Semantics Not Sounds. Authored by: Paul Thibodeau. Provided by: PLOS One. License: CC BY: Attribution Located at: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0153686.

All rights reserved content

- Psychology 101 – Wundt & James: Structuralism & Functionalism – Vook. Provided by: VookInc’s channel. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SW6nm69Z_IE

- Intro to Psychology – Crash Course Psychology #1. Authored by: CrashCourse. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vo4pMVb0R6M.

Public domain content

- woman at subway. Authored by: Eutah Mizushima. Provided by: Unsplash. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright Located at: https://www.pexels.com/photo/train-underground-subway-person-7533/.

the scientific study of mental processes and behavior

method for acquiring knowledge based on observation, including experimentation, rather than a method based only on forms of logical argument or previous authorities

understanding the conscious experience through introspection

focused on how mental activities helped an organism adapt to its environment

professional organization representing psychologists in the United States

study of how biology influences behavior

study of cognitions, or thoughts, and their relationship to experiences and actions

scientific study of development across a lifespan

long-standing traits and patterns that propel individuals to consistently think, feel, and behave in specific ways

consistent pattern of thought and behavior

area of psychology that focuses on the diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders and other problematic patterns of behavior

perspective that asserts that biology, psychology, and social factors interact to determine an individual’s health

(doctor of philosophy) doctoral degree conferred in many disciplinary perspectives housed in a traditional college of liberal arts and sciences

allows young scientists to further develop their research programs and broaden their research skills under the supervision of other professionals in the field