18.3 Singlehood, Marriage, & Cohabitation

Learning Objectives

- Provide some reasons individuals choose to remain single

- Describe the role of cohabitation in various types of relationships

- Describe how marriage rates in the United States have changed over time

- Explain cultural influences on marriage

Singlehood

Young adulthood

Being single is the most common lifestyle for people in their early 20s, and there has been an increase in the number of adults choosing to remain single. In 1960, only about 1 in 10 adults age 25 or older had never been married, in 2012 that had risen to 1 in 5 (Wang & Parker, 2014). While just over half (53%) of unmarried adults say they would eventually like to get married, 32 percent are not sure, and 13 percent do not want to get married.

It is projected that by the time people who are currently young adults reach their mid-40s and 50s, almost 25% of them may never have married. The U.S. is not the only country to see a rise in the number of single adults. The table below lists some of the reasons young adults give for staying single. In addition, adults are marrying later in life, cohabitating, and raising children outside of marriage in greater numbers than in previous generations. Young adults also have other priorities, such as education, and establishing their careers.

Table 18.3 Reasons for Staying Single

| Have not met the right person | 30% |

| Do not have financial stability | 27% |

| Not ready to settle down | 22% |

| Too young to marry | 22% |

adapted from Lally & Valentine-French, 2019

Historical trends in lifestyles and priorities may be reflected in changes in attitudes about the importance of marriage. In a recent Pew Research survey of Americans, respondents were asked to indicate which of the following statements came closer to their own views:

- “Society is better off if people make marriage and having children a priority.”

- “Society is just as well off if people have priorities other than marriage and children.”

Slightly more adults endorsed the second statement (50%) than those who chose the first (46%), with the remainder either selecting neither, both equally, or not responding (Wang & Parker, 2014). Young adults age 18-29 were more likely to endorse this second view than adults age 30 to 49; 67% and 53% respectively. In contrast, those age 50 or older were more likely to endorse the first statement (53%).

Middle Adulthood

According to a Pew Research study, 16 per 1,000 adults age 45 to 54 and 7 per 1000 age 55 and over have never-married in the U. S. (Wang & Parker, 2014). However, some of them may be living with a partner. In addition, some singles at midlife may be single through divorce or widowhood. DePaulo (2014) has challenged the idea that singles, especially the always single, fare worse emotionally and in health when compared to those married. DePaulo suggests there is a bias in how studies examine the benefits of marriage. Most studies focus on comparisons between married versus not married, which do not include a separate comparison between those always single, and those who are single because of divorce or widowhood. Her research has found that those who are married may be more satisfied with life than the divorced or widowed, but there is little difference between married and always single, especially when comparing those who are recently married with those who have been married for four or more years. It appears that once the initial blush of the honeymoon wears off, those who are wedded are no happier or healthier than those who remained single. This also suggests that it could be problematic for studies to consider the “married” category to be a homogeneous group.

Online Dating

Montenegro (2003) surveyed over 3,000 singles aged 40–69, and almost half of the participants reported their most important reason for dating was to have someone to talk to or do things with. Additionally, sexual fulfillment was also identified as an important goal for many. Alterovitz and Mendelsohn (2013) reviewed online personal ads for men and women over age 40 and found that romantic activities and sexual interests were mentioned at similar rates among the middle-age and young-old age groups, but less for the old-old age group.

Late Adulthood

Dating

Due to changing social norms and shifting cohort demographics, it has become more common for single older adults to be involved in dating and romantic relationships (Alterovitz & Mendelsohn, 2011). An analysis of widows and widowers ages 65 and older found that 18 months after the death of a spouse, 37% of men and 15% of women were interested in dating (Carr, 2004a). Unfortunately, opportunities to develop close relationships often diminish in later life as social networks decrease because of retirement, relocation, and the death of friends and loved ones (de Vries, 1996). Consequently, older adults, much like those younger, are increasing their social networks using technologies, including e-mail, chat rooms, and online dating sites (Fox, 2004; Wright & Query, 2004; Papernow, 2018).

Interestingly, older men and women parallel online dating information as those younger. Alterovitz and Mendelsohn (2011) analyzed 600 internet personal ads from different age groups, and across the life span, men sought physical attractiveness and offered status-related information more than women. With advanced age, men desired women increasingly younger than themselves, whereas women desired older men until ages 75 and over, when they sought men younger than themselves. Research has previously shown that older women in romantic relationships are not interested in becoming a caregiver or becoming widowed for a second time (Carr, 2004a).

Additionally, older men are more eager to repartner than are older women (Davidson, 2001; Erber & Szuchman, 2015). Concerns expressed by older women included not wanting to lose their autonomy, care for a potentially ill partner, or merge their finances with someone (Watson & Stelle, 2011). Older dating adults also need to know about threats to sexual health, including being at risk for sexually transmitted diseases, including chlamydia, genital herpes, and HIV. Nearly 25% of people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States are 50 or older (Office on Women’s Health, 2010b). Githens and Abramsohn (2010) found that only 25% of adults 50 and over who were single or had a new sexual partner used a condom the last time they had sex. Robin (2010) stated that 40% of those 50 and over have never been tested for HIV. These results indicate that educating all individuals, not just adolescents, on healthy sexual behavior is important.

Cohabitation

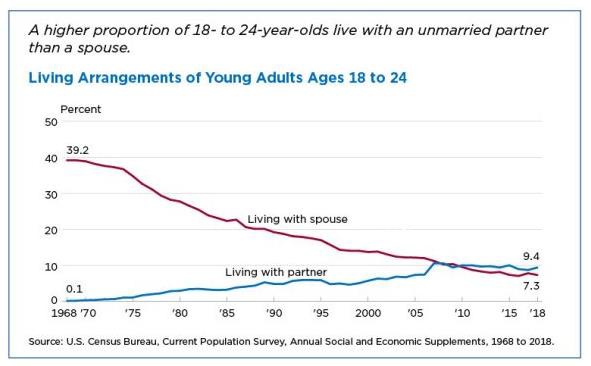

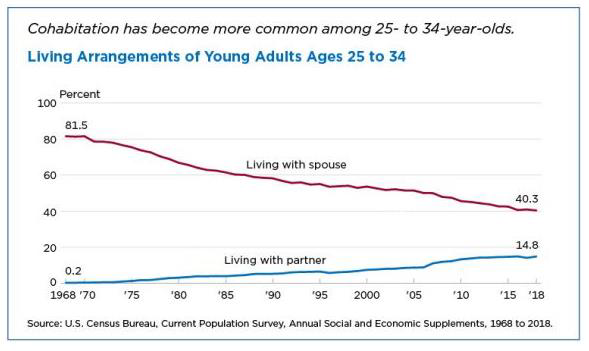

In American society, as well as in a number of other cultures, cohabitation has become increasingly commonplace (Gurrentz, 2018). For many emerging adults, age 18-24, cohabitation has become more common than marriage, as can be seen in Figure 18.13 below. While marriage is still a more common living arrangement for those 25-34, cohabitation has increased, while marriage has declined, as can be seen in Figure 18.14. Gurrentz also found that cohabitation varies by socioeconomic status. Those who are married tend to have higher levels of education, and thus higher earnings, or earning potential.

Copen et al. (2013) found that from 1995 to 2010 the median length of the cohabitation relationship had increased regardless of whether the relationship resulted in marriage, remained intact, or had since dissolved. In 1995 the median length of the cohabitation relationship was 13 months, whereas by 2010 it was 22 months. Cohabitation for all racial/ethnic groups, except for Asian women increased between 1995 and 2010 (see Table 18.4). Forty percent of the cohabitations transitioned into marriage within three years, 32% were still cohabitating, and 27% of cohabitating relationships had dissolved within the three years.

Table 18.4 Percentage of Women by Race/Ethnicity Whose First Union was Cohabitation

| 1995 | 2006-2010 | |

|---|---|---|

| Hispanic | 30% | 47% |

| White | 35% | 49% |

| Black | 35% | 49% |

| Asian | 22% | 22% |

adapted from Lally & Valentine-French, 2019; based on data from Copen et al., 2013

Three explanations have been given for the rise of cohabitation in Western cultures. The first notes that the increase in individualism and secularism, and the resulting decline in religious observance, has led to greater acceptance and adoption of cohabitation (Lesthaeghe & Surkyn, 1988). Moreover, the more people observe couples cohabitating, the more normal this relationship seems, and the more couples will then cohabitate. Thus, cohabitation is both a cause and the effect of greater cohabitation.

A second explanation focuses on the economic changes. The growth of industry and the modernization of many cultures has improved women’s social status, leading to greater gender equality and sexual freedom, with marriage no longer being the only long-term relationship option (Bumpass, 1990). A final explanation suggests that changes in employment requirements, with many jobs now requiring more advanced education, has led to a delay in marriage while youth pursue post-secondary education (Yu & Xie, 2015). Since most people marry soon after they have competed their highest level of education (e.g., people who complete only high school generally marry at 18-19 years old whereas people who graduate college typically marry at age 24-25), this might account for the increase in the age of first marriage in many nations.

Taken together, the greater acceptance of premarital sex, and the economic and educational changes would lead to a transition in relationships. Overall, cohabitation may become a step in the courtship process or may, for some, replace marriage altogether. Similar increases in cohabitation have also occurred in other industrialized countries. For example, rates are high in Great Britain, Australia, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. In fact, more children in Sweden are born to cohabiting couples than to married couples. The lowest rates of cohabitation in industrialized countries are in Ireland, Italy, and Japan (Benokraitis, 2005).

Cohabitation in Non-Western Cultures, the Philippines and China

Similar to other nations, young people in the Philippines are more likely to delay marriage, to cohabitate, and to engage in premarital sex as compared to previous generations (Williams et al., 2007). Despite these changes, however, many young people are still not in favor of these practices. Moreover, there is still a persistence of traditional gender norms as there are stark differences in the acceptance of sexual behavior out of wedlock for men and women in Philippine society. Young men are given greater freedom. In China, young adults are cohabitating in higher numbers than in the past (Yu & Xie, 2015). Unlike many Western cultures, in China adults with higher, rather than lower, levels of education are more likely to cohabitate. Yu and Xie suggest this may be because cohabitation is seen as more “innovative” or “modern,” and that those who are more highly educated may have had more exposure to Western cultures.

Cohabitation in Older Adults

Remarriage and Cohabitation

Older adults who remarry often find that their remarriages are more stable than those of younger adults. Kemp and Kemp (2002) suggest that greater emotional maturity may lead to more realistic expectations regarding marital relationships, leading to greater stability in remarriages in later life. Older adults are also more likely to be seeking companionship in their romantic relationships. Carr (2004a) found that older adults who have considerable emotional support from their friends were less likely to seek romantic relationships. In addition, older adults who have divorced often desire the companionship of intimate relationships without marriage. As a result, cohabitation is increasing among older adults, and like remarriage, cohabitation in later adulthood is often associated with more positive consequences than it is in younger age groups (King & Scott, 2005). No longer being interested in raising children, and perhaps wishing to protect family wealth, older adults may see cohabitation as a good alternative to marriage. In 2014, 2% of adults age 65 and up were cohabitating (Stepler, 2016b).

Living Apart Together

In addition to cohabiting there has been an increase in living apart together (LAT), which is “a monogamous intimate partnership between unmarried individuals who live in separate homes but identify themselves as a committed couple” (Benson & Coleman, 2016, p. 797). This trend has been found in several nations and is motivated by:

- A strong desire to be independent in day-to-day decisions

- Maintaining their own home

- Keeping boundaries around established relationships

- Maintaining financial stability

Besides the desire to be autonomous, there is also a need for companionship, sexual intimacy, and emotional support. According to Bensen and Coleman, there are differences in LAT among older and younger adults. Those who are younger often enter into LAT out of circumstances, such as the job market, and they frequently view this arrangement as a transitional stage. In contrast, 80% of older adults reported that they did not wish to cohabitate or marry. For some it was a conscious choice to live more independently. For instance, older women desired the LAT lifestyle as a way of avoiding the traditional gender roles that are often inherent in relationships where couples live together. However, some older adults become LATs because they fear social disapproval from others if they were to live together.

Marriage

Marriage in the United States

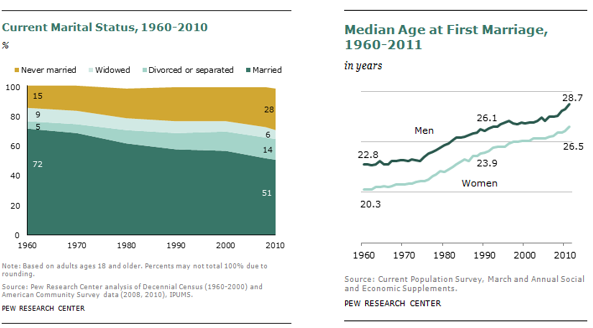

Marriage has experienced changes in the United States over the last sixty years. In 1960, 72% of adults age 18 or older were married, in 2010 this number had dropped to barely half (Wang & Taylor, 2011). At the same time, the age of first marriage has been increasing for both men and women. In 1960, the average age for first marriage was 20 for women and 23 for men. By 2010 this had increased to 26.5 for women and nearly 29 for men (see Figure 8.8). Many of the explanations for increases in singlehood and cohabitation provided previously (especially increasing number of years of education) can also account for the drop and delay in marriage.

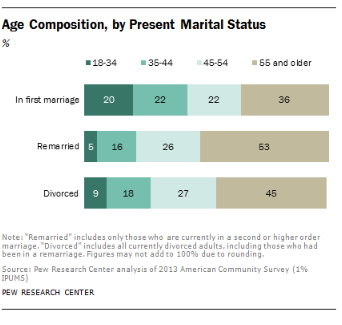

Across all periods of adulthood, marriage rates are declining as more people are cohabitating, more are deciding to stay single, and more are getting married at a later age. However, marriage is still the most common relationship status for middle-aged adults in the United States. As you can see in the Figure 18.16, 48% of adults age 45-54 are married; either in their first marriage (22%) or have remarried (26%).

As previously mentioned, martial satisfaction often decreases after the birth of the first child. However, some research also suggests that marital satisfaction tends to increase for many couples in midlife as children are leaving home (Landsford et al., 2005). Not all researchers agree. They suggest that those who are unhappy with their marriage are likely to have gotten divorced by now, making the quality of marriages later in life only look more satisfactory (Umberson et al., 2005).

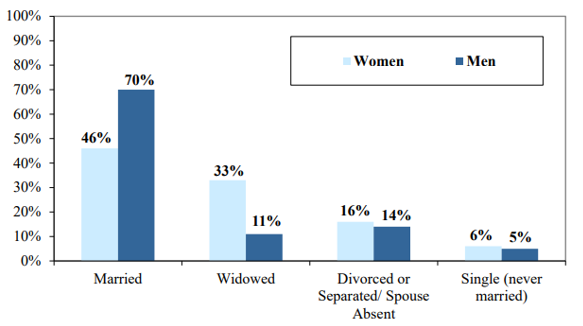

Marriage continues to be common into older adulthood. As can be seen in Figure 18.17, the most common living arrangement for older adults in 2017 was marriage (AOA, 2017). This status was more common for older men than for older women, who based on differences in average life expectancy, typically outlive their husbands.

Marriage Worldwide

Cohen (2013) reviewed data assessing most of the world’s countries and found that rates of marriage have declined universally during the last several decades. Although this decline has occurred in both poor and rich countries, the countries with the biggest drops in marriage were mostly rich: France, Italy, Germany, Japan and the U.S. Cohen argues that these declines are due not only to individuals delaying marriage, but also to higher rates of non-marital cohabitation. Delays or decreases in marriage are associated with higher income and lower fertility rates that are observed worldwide.

Same-Sex Marriage

In June 26, 2015, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution guarantees same-sex marriage. The decision indicated that limiting marriage to only heterosexual couples violated the 14th amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law. This ruling occurred 11 years after same-sex marriage was first made legal in Massachusetts, and at the time of the high court decision, 36 states and the District of Columbia had legalized same sex marriage. Worldwide, 29 countries currently have national laws allowing gay and lesbian couples to marry (Pew Research Center, 2019).

Cultural Influences on Marriage

Many cultures have both explicit and unstated rules that specify who is an appropriate mate. Consequently, mate selection is not completely left to the individual. Rules of endogamy indicate the groups we should marry within and those we should not (Witt, 2009). For example, many cultures specify that people marry within their own race, social class, age group, or religion. For example, for most of its history, the US upheld laws that criminalized marriage between people from different races; the last such laws were struck down by a Supreme Court ruling in 1967. Endogamy reinforces the cohesiveness of the group. Additionally, these rules encourage homogamy or marriage between people who share social characteristics. The majority of marriages in the U. S. are homogamous with respect to race, social class, age and to a lesser extent, religion. Homogamy is also seen in couples with similar personalities and interests.

Arranged Marriages and Elopement

Historically, marriage was not a personal choice, but one made by one’s family. Arranged marriages often ensured proper transference of a family’s wealth and the support of ethnic and religious customs. Such marriages were considered a marriage of families rather than of individuals. In Western Europe, starting in the 18th century, the notion of personal choice in a marital partner slowly became the norm. Arranged marriages were seen as “traditional” and marriages based on love “modern.” Many of these early “love” marriages were accomplished by eloping (Thornton, 2005).

Around the world, more and more young couples are choosing their own partners, even in nations where arranged marriages are still the norm, such as India and Pakistan. Desai and Andrist (2010) found that in India only 5% of the women they surveyed, aged 25-49, had a primary role in choosing their partner. Only 22% knew their partner for more than one month before they were married. However, the younger cohort of women was more likely to have been consulted by their families before their partner was chosen than were the older cohort, suggesting that family views are changing about personal choice. Allendorf (2013) reports that this 5% figure may also underestimate young people’s choice, as only women were surveyed. Many families in India are increasingly allowing sons veto power over the parents’ choice of his future spouse, and some families give daughters the same say.

Happiness and Marital Satisfaction

Although research frequently suggests that marriage is associated with higher rates of happiness, this does not guarantee that getting married will make you happy! The quality of one’s marriage matters greatly. When a person remains in a problematic marriage, it takes an emotional toll. Indeed, a large body of research shows that people’s overall life satisfaction is affected by their satisfaction with their marriage (Umberson et al., 2005; Proulx et al., 2007). Marital satisfaction has peaks and valleys during the course of the family life cycle. Rates of happiness are highest in the years prior to the birth of the first child. It hits a low point with the arrival of the second (or more) child. Children bring new demands and expectations to the marital relationship, along with more financial hardships and stress. Many people who are comfortable with their roles as partners find added parental duties and expectations more challenging to meet. Some couples elect not to have children, for a variety of reasons. These child-free couples, for example, may choose to focus more time and attention on their partners, careers, and interests.

Gender Role Changes

With the coming of the first child, gender roles in committed relationships typically become more traditional. In western countries, women often take on more domestic responsibilities and childrearing duties at this time (Cooke, 2010; Saginak & Saginak, 2005). for many women, this shift away from a largely egalitarian relationship may be one of the reasons that martial satisfaction suffers. The most egalitarian gender roles typically occur when children are older, and in the empty nest stage.

Link to Learning

One way marriages vary is with regard to the reason the partners are married. Some marriages have intrinsic value: the partners are together because they enjoy, love, and value one another. Marriage is not thought of as a means to another end, instead it is regarded as an end in itself. These partners look for someone they are drawn to, and with whom they feel a close and intense relationship. Other marriages called utilitarian marriages are unions entered into primarily for practical reasons. For example, the marriage brings financial security, children, social approval, housekeeping, political favor, a good car, a great house, and so on.

There have been a few attempts to establish a typological framework for marriages. The best-known is that by Olson (1993), who referred to five typical kinds of marriage. Using a sample of 6,267 couples, Olson & Fowers (1993) identified eleven relationship domains that covered areas related to relationship satisfaction and more functional areas related to marriage. So, five of the eleven domains included areas such as marital satisfaction, communication, and things like financial management, parenting, and egalitarian roles. Using these eleven areas they came up with five kinds of marriage:

- Vitalized. Very high relationship quality. Tend to belong in a higher income bracket. Happy with their spouse across all areas—personality, communication, roles, and expectations.

- Harmonious relationships. These marriages have some areas of tension and disagreement but there is still broad agreement on major issues. Lack of agreement on parenting was the primary feature of this group, although the couples still scored highly on relationship quality.

- Traditional marriages. These marriages show much less emphasis on emotional closeness, but still score slightly above average on connection. There are high levels of compatibility in relation to parenting.

- Conflicted. These marriages accomplish functional goals such as parenting but are marked by a great deal of interpersonal disagreement. Communication and conflict resolution scores are extremely low.

- Devitalized. These marriages have low scores across all eleven areas—little interpersonal closeness and little agreement on family roles.

One aspect of this early study is the link between marital satisfaction and income/college education. Olson & Fowers (1993) were one of the first studies to point to this link, which is now commonly accepted. The less well-off are more prone to divorce, as are those with less college-level education. Income and college education are of course linked, and there is now increasing concern that marital dissolution and broader patterns of social inequality are now inextricably linked. [1]

Try It

Marital Communication

Advice on how to improve one’s marriage is centuries old. One of today’s experts on marital communication is John Gottman. Gottman differs from many marriage counselors in his belief that having a good marriage does not depend on compatibility, rather, the way that partners communicate with one another is crucial. At the University of Washington in Seattle, Gottman has measured the physiological responses of thousands of couples as they discuss issues which have led to disagreements. Fidgeting in one’s chair, leaning closer to or further away from the partner while speaking, and increases in respiration and heart rate are all recorded and analyzed, along with videotaped recordings of the partners’ exchanges.

Gottman believes he can accurately predict whether or not a couple will stay together by analyzing their communication. In marriages destined to fail, partners engage in the “marriage killers” such as contempt, criticism, defensiveness, and stonewalling. Each of these undermines the politeness and respect that healthy marriages require. According to Gottman, stonewalling, or shutting someone out, is the strongest sign that a relationship is destined to fail. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Gottman’s work is the emphasis on the fact that marriage is about constant negotiation rather than conflict resolution.

What Gottman terms perpetual problems, are responsible for 69% of conflicts within marriage. For example, if someone in a couple has said, “I am so sick of arguing over this,” then that may be a sign of a perpetual problem. While this may seem problematic, Gottman argues that couples can still be connected despite these perpetual problems if they can laugh about it, treat it as a “third thing” (not reducible to the perspective of either party), and recognize that these are part of relationships that need to be aired and dealt with as best you can. It is somewhat refreshing to hear that differences lie at the heart of marriage, rather than a rationale for its dissolution!

Link to Learning

Listen to NPR’s Act One: What Really Happens in Marriage to hear John Gottman talk about his work.

Try It

References (Click to expand)

Administration on Aging. (2017). 2017 Profile of older Americans. Retrieved from: https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2017OlderAmericansProfile.pdf

Allendorf, K. (2013). Schemas of marital change: From arranged marriages to eloping for love. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75, 453-469.

Alterovitz, S. S., & Mendelsohn, G. A. (2011). Partner preferences across the lifespan: Online dating by older adults. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 1, 89-95.

Alterovitz, S. S., & Mendelsohn, G. A. (2013). Relationship goals of middle-aged, young-old, and old-old Internet daters: An analysis of online personal ads. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 159–165.

Benokraitis, N. V. (2005). Marriages and families: Changes, choices, and constraints (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.Benson, J.J., & Coleman, M. (2016). Older adults developing a preference for living apart together. Journal of Marriage and Family, 18, 797-812.

Bumpass, L. L. (1990). What’s happening to the family? Interactions between demographic and institutional change. Demography, 27(4), 483–498.

Carr, D. (2004a). The desire to date and remarry among older widows and widowers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1051– 1068.

Cohen, P. (2013). Marriage is declining globally. Can you say that? Retrieved from https://familyinequality.wordpress.com/2013/06/12/marriage-is-declining/

Cooke, L. P. (2010). The politics of housework. In J. Treas & S.Drobnic (Eds.), Dividing the domestic: Men, women, and household work in cross-national perspective (pp. 59-78). Standford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Copen, C.E., Daniels, K., & Mosher, W.D. (2013) First premarital cohabitation in the United States: 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National health statistics reports; no 64. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Davidson, K. (2001). Late life widowhood, selfishness and new partnership choices: A gendered perspective. Ageing and Society, 21, 297–317.

DePaulo, B. (2014). A singles studies perspective on mount marriage. Psychological Inquiry, 25(1), 64-68.

Desai, S., & Andrist, L. (2010). Gender scripts and age at marriage in India. Demography, 47, 667-687.

de Vries, B. (1996). The understanding of friendship: An adult life course perspective. In C. Magai & S. H. McFadden (Eds.), Handbook of emotion, adult development, and aging (pp. 249–268). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Erber, J. T., & Szuchman, L. T. (2015). Great myths of aging. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons. Erikson, E. H. (1982). The life cycle completed. New York, NY: Norton & Company.

Fox, S. (2004). Older Americans and the Internet. PEW Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/report_display.asp?r_117

Githens, K., & Abramsohn, E. (2010). Still got it at seventy: Sexuality, aging, and HIV. Achieve, 1, 3-5.

Gurrentz, B. (2018). For young adults, cohabitation is up, and marriage is down. US. Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/11/cohabitaiton-is-up-marriage-is-down-for-young-adults.html.

Kemp, E. A., & Kemp, J. E. (2002). Older couples: New romances: Finding and keeping love in later life. Berkeley, CA: Celestial Arts.

King, V., & Scott, M. E. (2005). A comparison of cohabitating relationships among older and younger adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(2), 271-285.

Landsford, J. E., Antonucci, T.C., Akiyama, H., & Takahashi, K. (2005). A quantitative and qualitative approach to social relationships and well-being in the United States and Japan. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 36, 1-22.

Lesthaeghe, R. J., & Surkyn, J. (1988). Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Development Review 14(1), 1–45.

Montenegro, X. P. (2003). Lifestyles, dating, and romance: A study of midlife singles. Washington, DC: AARP.

Office on Women’s Health. (2010b). Sexual health. Retrieved from http://www.womenshealth.gov/aging/sexual-health/

Papernow, P. L. (2018). Recoupling in midlife and beyond: From love at last to not so fast. Family Processes, 57(1), 52-69.

Pew Research Center. (2019). Same-sex marriage around the world. Retrieved from https://www.pewforum.org/fact-sheet/gay-marriage-around-the-world/

Proulx, C. M., Helms, H. M., & Buehler, C. (2007). Marital Quality and Personal Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(3), 576–593

Robin, R. C. (2010). Grown-up, but still irresponsible. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/10weekinreview/10rabin.html>.

Saginak, K. A., & Saginak, M. A. (2005). Balancing work and family: Equity, gender, and marital satisfaction. Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 13, 162-166.

Stepler, R. (2016b). Living arrangements of older adults by gender. Pew Research Center Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2016/02/18/2-living-arrangements-of-older-americans-by-gender/

Thornton, A. (2005). Reading history sideways: The fallacy and enduring impact of the developmental paradigm on family life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Umberson, D., Williams, K., Powers, D., Chen, M., & Campbell, A. (2005). As good as it gets? A life course perspective on marital quality. Social Forces, 81, 493-511.

Wang, W., & Parker, K. (2014). Record share of Americans have never married: As values, economics and gender patterns change. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2014/09/2014-09-24_Never-Married-Americans.pdf

Wang, W., & Taylor, P. (2011). For Millennials, parenthood trumps marriage. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Williams, L., Kabamalan, M., & Ogena, N. (2007). Cohabitation in the Philippines: Attitudes and behaviors among young women and men. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(5), 1244–1256.Witt, J. (2009). SOC. New York: McGraw Hill.Wright, K. B., & Query, J. L. (2004). Online support and older adults: A theoretical examination of benefits and limitations of computer-mediated support networks for older adults and possible health outcomes. In J. Nussbaum & J. Coupland (Eds.), Handbook of communication and aging research (2nd ed., pp. 499–519). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.Yu, J., & Xie, Y. (2015). Cohabitation in China: Trends and determinants. Population & Development Review, 41 (4), 607-628.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

CC Licensed Content, Shared Previously

- “Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0/modified (new introduction text) by Dan Grimes, Portland State University

- Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- Trends in Dating, Cohabitation, and Marriage. Authored by: Margaret Clark-Plaskie for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology . Authored by: Laura Overstreet . Located at: http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Section on Love and the Internet. Authored by: Debi Brannan and Cynthia D. Mohr . Provided by: Western Oregon University, Portland State University. Located at: https://nobaproject.com/modules/love-friendship-and-social-support. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cohabitation. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cohabitation. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Family; courtship and marriage. Authored by: Joel A. Muraco . Provided by: University of Wisconsin, Green Bay. Located at: https://nobaproject.com/modules/the-family. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Variations in Family Life. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/14-2-variations-in-family-life. Project: Sociology 3e. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/14-2-variations-in-family-life

Media Attributions

- cohab1 © US Census Bureau is licensed under a Public Domain license

- cohab2 © US Census Bureau is licensed under a Public Domain license

- maritalstatus © Pew Research Center

- agemaritalstatus © Pew Research Center

- maritalstatus65 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- in-lieu-in-view-photography-lj3BEGiZ2fw-unsplash-2 © In Lieu In View Photography is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

All Rights Reserved Content

- ST_2014-11-14_remarriage-06 © Pew Research Center is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license