11.1 Foundations of Morality

Learning Objectives

- Explain the role of conscience in moral development

- Explain theory of mind

- Describe theory of mind in individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Conscience

Social and personality development is built from social, biological, and representational influences. These influences result in important developmental outcomes that matter to children, parents, and society: a young adult’s capacity to engage in socially constructive actions (helping, caring, sharing with others), to curb hostile or aggressive impulses, to live according to meaningful moral values, to develop a healthy identity and sense of self, and to develop talents and achieve success in using them. These are some of the developmental outcomes that denote social and emotional competence.

These achievements of social and personality development derive from the interaction of many social, biological, and representational influences. Consider, for example, the development of conscience, which is an early foundation for moral development.

Conscience consists of the cognitive, emotional, and social influences that cause young children to create and act consistently with internalized standards of right and wrong (Kochanska, 2002). It emerges from young children’s experiences with parents, particularly in the development of a mutually responsive relationship that motivates young children to respond constructively to the parents’ requests and expectations. Biologically-based temperament is involved, as some children are temperamentally more capable of motivated self-regulation (a quality called effortful control) than are others, while some children are more prone to the fear and anxiety that parental disapproval can evoke. The development of conscience is influenced by having a good fit between the child’s temperamental qualities and the ways parents communicate and reinforce behavioral expectations.

Conscience development also expands as young children begin to represent moral values and think of themselves as moral beings. By the end of the preschool years, for example, young children develop a “moral self” by which they think of themselves as people who want to do the right thing, who feel badly after misbehaving, and who feel uncomfortable when others misbehave. In the development of conscience, young children become more socially and emotionally competent in a manner that provides a foundation for later moral conduct (Thompson, 2012).

Link to Learning

To learn about moral development during early childhood, please read the following article from Open University: “Moral Behaviour”

Theory of Mind

Theory of mind refers to the ability to think about other people’s thoughts (also known as meta-cognition—that is, thinking about thinking). Theory of mind is the understanding that other people experience mental states (for instance, thoughts, beliefs, feelings, or desires) that are different from our own, and that their mental states are what guide their behavior. This skill, which emerges in early childhood, helps humans to infer, predict, and understand the reactions of others, thus playing a crucial role in social development and in promoting competent social interactions.

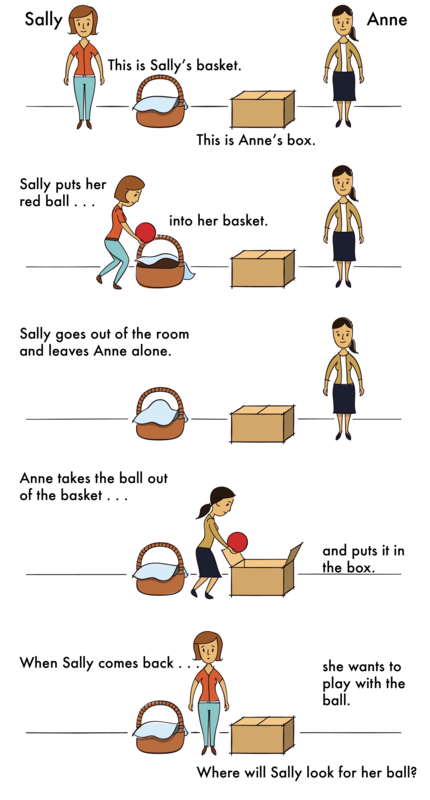

One common method for determining if a child has reached this mental milestone is called the false belief task. The research began with a clever experiment by Wimmer and Perner (1983), who tested whether children can pass a false-belief test (see Figure 11.3). The child is shown a picture story of Sally, who puts her ball in a basket and leaves the room. While Sally is out of the room, Anne comes along and takes the ball from the basket and puts it inside a box. The child is then asked where Sally thinks the ball is located when she comes back to the room. Is she going to look first in the box or in the basket? The right answer is that she will look in the basket, because that is where she put it and thinks it is; but we have to infer this false belief against our own better knowledge that the ball is in the box. This is very difficult for children before the age of four because of the cognitive effort it takes.

Three-year-olds have difficulty distinguishing between what they once thought was true and what they now know to be true. They feel confident that what they know now is what they have always known (Birch & Bloom, 2003). You could say that their perspectives are fused: whatever is actually true is what they and everyone else thinks. Even adults need to think through this task (Epley et al., 2004). To be successful at solving this type of task, the child must separate three things: (1) what is true; (2) what they themselves think (which can be false); and (3) what someone else thinks (which can be different from what they think as well as different from reality). Can you see why this task is so complex?

In Piagetian terms, children must give up a tendency toward egocentrism. The child must also understand that what guides people’s actions and responses are what they believe rather than what is actually true. In other words, people can mistakenly believe things that are false (called false beliefs) and will act based on this false knowledge. Consequently, prior to age four children are rarely successful at solving such tasks (Wellman et al. 2001).

Researchers examining the development of theory of mind have been concerned by the overemphasis on the mastery of false belief as the primary measure of whether a child has attained theory of mind. Two-year-olds understand the diversity of desires, yet as noted earlier it is not until age four or five that children grasp false beliefs, and often not until middle childhood do they understand that people may hide how they really feel. In part, because children’s understanding is fused: in early childhood children do not differentiate genuine feelings from the expression of feelings. They have difficulty hiding how they really feel (e.g., saying thank you for a gift they do not really like). Wellman and his colleagues (Wellman, et al., 2006) suggest that theory of mind is comprised of a number of components, each with its own developmental timeline (see Table 11.1).

Watch It

Watch this video to see the Sally-Anne test in action.

You can view the transcript for “Sally Anne Test..mpg” here (opens in new window).

Table 11.1 Components of Theory of Mind

| Stage, Component | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Desire Psychology (ages 2-3) | ||

| Diverse-desires | Understanding that two people may have different desires regarding the same object. | |

| Belief Psychology (ages 3 or 4 to 5) | ||

| Diverse-beliefs | Understanding that two people may hold different beliefs about an object. | |

| Knowledge access (knowledge/ignorance) | Understanding that people may or may not have access to information. | |

| False belief | Understanding that someone might hold a belief based on false information. |

adapted from Lally & Valentine-French, 2019

Those in early childhood in the US, Australia, and Germany develop theory of mind in the sequence outlined in Table 11.1. Yet, Chinese and Iranian preschoolers acquire knowledge access before diverse beliefs (Shahaeian et al., 2011). Shahaeian and colleagues suggested that cultural differences in child-rearing may account for this reversal. Parents in collectivistic cultures, such as China and Iran, emphasize conformity to the family and cultural values, greater respect for elders, and the acquisition of knowledge and academic skills more than they do autonomy and social skills (Frank et al., 2010). This could reduce the degree of familial conflict of opinions expressed in the family. In contrast, individualistic cultures encourage children to think for themselves and assert their own opinion, and this could increase the risk of conflict in beliefs being expressed by family members. As a result, children in individualistic cultures would acquire insight into the question of diversity of belief earlier, while children in collectivistic cultures would acquire knowledge access earlier in the sequence. The role of conflict in aiding the development of theory of mind may account for the earlier age of onset of an understanding of false belief in children with siblings, especially older siblings (McAlister & Petersen, 2007; Perner et al. 1994).

This awareness of the existence of theory of mind is part of social intelligence, such as recognizing that others can think differently about situations. It helps us to be self-conscious or aware that others can think of us in different ways and it helps us to be able to be understanding or be empathic toward others. Moreover, this “mind reading” ability helps us to anticipate and predict people’s actions. The awareness of the mental states of others is important for communication and social skills.

Watch It

Watch as researchers demonstrate several versions of the false belief test to assess the theory of mind in young children.

You can view the transcript for “The theory of mind test” here (opens in new window).

You can view the transcript for “The “False Belief” Test: Theory of Mind” here (opens in new window).

Impaired Theory of Mind in Individuals with Autism

People with autism or an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) typically show an impaired ability to recognize other people’s minds. Under the DSM-5, autism is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction across multiple contexts, as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. These deficits are present in early childhood, typically before age three, and lead to clinically significant functional impairment. Symptoms may include lack of social or emotional reciprocity, stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language, and persistent preoccupation with unusual objects.

About half of parents of children with ASD notice their child’s unusual behaviors by age 18 months, and about four-fifths notice by age 24 months, but often a diagnoses comes later, and individual cases vary significantly. Typical early signs of autism include:

- No babbling by 12 months.

- No gesturing (pointing, waving, etc.) by 12 months.

- No single words by 16 months.

- No two-word (spontaneous, not just echolalic) phrases by 24 months.

- Loss of any language or social skills, at any age.

Children with ASD experience difficulties with explaining and predicting other people’s behavior, which leads to problems in social communication and interaction. Children who are diagnosed with an autistic spectrum disorder usually develop the theory of mind more slowly than other children and continue to have difficulties with it throughout their lives.

For testing whether someone lacks the theory of mind, the Sally-Anne test is performed. The child sees the following story: Sally and Anne are playing. Sally puts her ball into a basket and leaves the room. While Sally is gone, Anne moves the ball from the basket to the box. Now Sally returns. The question is: where will Sally look for her ball? The test is passed if the child correctly assumes that Sally will look in the basket. The test is failed if the child thinks that Sally will look in the box. Children younger than four and older children with autism will generally say that Sally will look in the box.

Try It

References (Click to expand)

Birch, S., & Bloom, P. (2003). Children are cursed: An asymmetric bias in mental-state attribution. Psychological Science, 14(3), 283-286.

Epley, N., Morewedge, C. K., & Keysar, B. (2004). Perspective taking in children and adults: Equivalent egocentrism but differential correction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 760–768.

Frank, G., Plunkett, S. W., & Otten, M. P. (2010). Perceived parenting, self-esteem, and general self-efficacy of Iranian American adolescents. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 19, 738-746.

Kochanska, G. (2002). Mutually responsive orientation between mothers and their young children: A context for the early development of conscience. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(6), 191-195.

McAlister, A. R., & Peterson, C. C. (2007). A longitudinal study of siblings and theory of mind development. Cognitive Development, 22, 258-270.

Perner, J., Ruffman, T., & Leekam, S. R. (1994). Theory of mind is contagious: You catch from your sibs. Child Development, 65, 1228-1238.

Shahaeian, A., Peterson, C. C., Slaughter, V., & Wellman, H. M. (2011). Culture and the sequence of steps in theory of mind development. Developmental Psychology, 47(5), 1239-1247.

Thompson, R. A. (2012). Whither the preconventional child? Toward a life‐span moral development theory. Child development perspectives, 6(4), 423-429.

Wellman, H.M., Cross, D., & Watson, J. (2001). Meta-analysis of theory of mind development: The truth about false belief. Child Development, 72(3), 655-684.

Wellman, H. M., Fang, F., Liu, D., Zhu, L, & Liu, L. (2006). Scaling theory of mind understandings in Chinese children. Psychological Science, 17, 1075-1081.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition, 13, 103–128.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

CC Licensed Content

- “Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0

- Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- “Self-Regulation” by Ellen Skinner & Eli Labinger, Portland State University is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0

- Child Growth and Development by College of the Canyons, Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Rymond and is used under a CC BY 4.0 international license

- “Theory of Mind.” Authored by: Stephanie Loalada for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/chapter/theory-of-mind/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology. Authored by: Laura Overstreet. Located at: http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Theory of Mind Sally-Anne test. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theory_of_mind. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Autism. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autism. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Media Attributions

- Boy in thought. Authored by: mbpogue. Provided by: pxhere. Located at: https://pxhere.com/en/photo/1428411. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- theoryofmind © Bertram Malle is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

All Rights Reserved Content

- The False Belief Test: Theory of Mind. Provided by: 007IceWeasel. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8hLubgpY2_w. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- The theory of mind test. Provided by: The Globe and the Mail. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YGSj2zY2OEM. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Sally Anne Test. Authored by: markmcdermott. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=10&v=QjkTQtggLH4. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License