18.4 Divorce

The Human Development Teaching & Learning Group

Learning Objectives

- Discuss divorce and remarriage during middle adulthood

- Describe the role of children in decisions to divorce and remarry

- Explain what a blended family is and describe ways to smooth the transition into such a family

Divorce

Divorce refers to the legal dissolution of a marriage. Depending on societal factors, divorce may be more or less of an option for married couples. Despite popular belief, divorce rates in the United States actually declined for many years during the 1980s and 1990s, and only just recently started to climb back up—landing at just below 50% of marriages ending in divorce today (Marriage & Divorce, 2016); however, it should be noted that divorce rates increase for each subsequent marriage, and there is considerable debate about the exact divorce rate. Are there specific factors that can predict divorce? Are certain types of people or certain types of relationships more or less at risk for breaking up? Indeed, there are several factors that appear to be either risk factors or protective factors.

Pursuing education decreases the risk of divorce. So too does waiting until we are older to marry. Likewise, if our parents are still married we are less likely to divorce. Factors that increase our risk of divorce include having a child before marriage and living with multiple partners before marriage, known as serial cohabitation (cohabitation with one’s expected marital partner does not appear to have the same effect). Of course, societal and religious attitudes must also be taken into account. In societies that are more accepting of divorce, divorce rates tend to be higher. Likewise, in religions that are less accepting of divorce, divorce rates tend to be lower. See Lyngstad & Jalovaara (2010) for a more thorough discussion of divorce risk.

Divorce in Families With Children

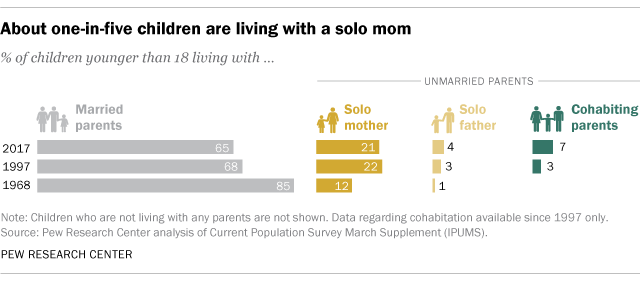

Family structures have changed significantly over the years. In 1960, 92% of children resided with married parents, while only 5% had parents who were divorced or separated and 1% resided with parents who had never been married. By 2008, 70% of children resided with married parents, 15% had parent who were divorced or separated, and 14% resided with parents who had never married (Pew Research Center, 2010). In 2017, only 65% of children lived with two married parents, while 32% (24 million children younger than 18) lived with an unmarried parent (Livingston, 2018). Some 3% of children were not living with any parents, according to the U.S. Census Bureau data.

Most children in unmarried parent households in 2017 were living with a solo mother (21%), but a growing share were living with cohabiting parents (7%) or a sole father (4%) (see Figure 4.3). The increase in children living with solo or cohabiting parents is thought to be due to overall declines in marriage, combined with increases in divorce. Of concern is that children who live with a single parent are also more likely to be living in reduced socioeconomic circumstances. Specifically, while only 8% of married couples live below the poverty line, 30% of solo mothers, 17% of solo fathers, and 16% of families with a cohabitating couple live in poverty (Livingston, 2018).

Divorce and its effects on children

Research suggests that divorce typically is difficult for children. For example, Weaver and Schofield (2015) selected a subsample of families from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development, and found that children from divorced families had significantly more behavior problems than those from a matched sample of children from non-divorced families. These problems were evident immediately after the separation and also in early and middle adolescence. An analysis of the factors that make adjustment to divorce easier or harder indicated that children exhibited more externalizing behaviors if the family had fewer financial resources before the separation. Researchers suggested that perhaps a lower income and lack of educational and community resources contributed to the stress involved in the divorce. Additional factors predicting fewer behavior problems included a post-divorce home that was more supportive and stimulating, and a mother who was more sensitive and less depressed.

Certain losses are inevitable in a divorce. Children miss the parent they no longer see as frequently, as well as any other family members who become estranged because of the divorce. Children may grieve the loss of the family as a unit, and reminisce about “the good old days” when the whole family lived together. The process of divorce is typically accompanied by change, disruption, and confusion, as well as increased family conflict. Because they are themselves dealing with the divorce, parents are typically stressed out and fewer resources are available for parenting.

Very often, divorce also means a change in the amount of money coming into the household. Custodial mothers experience a 25% to 50% drop in their family income, and even five years after the divorce they have reached only 94% of their pre-divorce family income (Anderson, 2018). As a result, children experience new constraints on spending or entertainment. School-aged children, especially, may notice that they can no longer have toys, clothing or other items to which they have grown accustomed. Or it may mean that there is less eating out or participation in recreational activities. The custodial parent may experience stress at not being able to rely on child support payments or having the same level of income as before. This can affect decisions regarding healthcare, vacations, rents, mortgages and other expenditures, and the stress can result in less happiness and relaxation in the home. The parent who has to take on more work may also be less available to the children. Children may also have to adjust to other changes accompanying a divorce. The divorce might mean moving to a new home and changing schools or friends. It might mean leaving a neighborhood that has meant a lot to them as well.

Short-term consequences

The initial consequences of divorce can be relatively serious for children. They often express anger and other indicators of distress and, and show increased problems in major areas of functioning: more unruly and demanding behavior at home, poorer school performance, and more difficulty with peers. Children may also lose some of their confidence, trust, and security in relationships. About twice as many children show serve problems following divorce (20-25%), compared to a normative base rate of about 10%. Difficulties typically peak at about one year, leading some researchers to conclude that, in terms of familial problems, the consequences of divorce are second only to parental death. However, not all children of divorce suffer negative consequences (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). Children may be given more opportunity to discover their own abilities and gain independence that fosters self-esteem. If divorce means a reduction in family conflict, children may feel relief. Furstenberg and Cherlin (1991) believe that the primary factor influencing the way that children adjust to divorce is the way the custodial parent adjusts. If that parent is adjusting well, children will benefit. This may explain a good deal of the variation we find in children of divorce.

Long-term consequences

Although children show much recovery following divorce, small effects persist. Compared to children from never-divorced families, children of divorce show lower levels of achievement in school, self-esteem, and social competence, as well as slightly elevated levels of emotional and behavioral problems (boys show externalizing and girls internalizing behavior). During adolescence, children of divorce also have slightly higher rates of sexual activity and pregnancy, are less likely to graduate from high school, and more troubled romantic relationships.

To some extent, the relationships of adult children of divorce have also been found to be more problematic than those of adults from intact homes. For 25 years, Hetherington and Kelly (2002) followed a large sample of children of divorce and those whose parents stayed together. The results indicated that 25% of adults whose parents had divorced experienced social, emotional, or psychological problems compared with only 10% of those whose parents remained married. For example, children of divorce have more difficulty forming and sustaining intimate relationships as young adults, are more dissatisfied with their marriages, and consequently more likely to get divorced themselves (Arkowitz & Lilienfeld, 2013). One of the most commonly cited long-term effects of divorce is that children of divorce may have lower levels of education and occupational status (Richter & Lemola, 2017). This may be a consequence of lower income and resources for funding education rather than to divorce per se. In those households where economic hardship does not occur, there may be no impact on long-term economic status (Drexler, 2005).

Child characteristics

Certain characteristics of the child can also make post-divorce adjustment easier or harder. Specifically, children with an easygoing temperament, who problem-solve well, and seek social support manage better after divorce. Children who have a difficult temperament may experience more difficulties. Boys typically display more overt problems than girls, and may increasingly act out during the transition. A further protective factor for children is intelligence (Weaver & Schofield, 2015). Children with higher IQ scores appear to be buffered from the effects of divorce. Children’s ability to deal with a divorce may also depend on their age. Infants and preschool-age children may suffer the heaviest impact from the loss of routine that the marriage offered (Temke 2006). Younger children often take divorce harder because they blame themselves, and can break their parent hearts a little if they promise to be good if only their parents will get back together again. Research has found that divorce may be most difficult for school-aged children, as they are old enough to understand the separation but not old enough to understand the reasoning behind it. Older teenagers are more likely to recognize the conflict that led to the divorce but may still feel fear, loneliness, guilt, and pressure to choose sides. Older children often turn to peers and their families to escape from their home situation.

Helping children adjust to divorce

According to Arkowitz and Lilienfeld (2013), long-term harm from parental divorce is not inevitable, however, and children can navigate the experience successfully. A variety of factors can positively contribute to the child’s adjustment. For example, children manage better when parents limit conflict, and provide warmth, emotional support and appropriate discipline. Further, children cope better when they reside with a well-functioning parent and have access to social support from peers and other adults. Those at a higher socioeconomic status may fare better because some of the negative consequences of divorce are a result of financial hardship rather than divorce per se (Anderson, 2014; Drexler, 2005). It is important when considering the research findings on the consequences of divorce for children to consider all the factors that can influence the outcome, as some of the negative consequences associated with divorce are due to preexisting problems (Anderson, 2014). Although they may experience more problems than children from non-divorced families, most children of divorce lead happy, well-adjusted lives and develop strong, positive relationships with their custodial parent (Seccombe & Warner, 2004).

In a study of college-age respondents, Arditti (1999) found that increasing closeness and a movement toward more democratic parenting styles were experienced following divorce. Children from single-parent families also talk to their mothers more often than children of two-parent families (McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994). Others have also found that relationships between mothers and children become closer and stronger (Guttman, 1993) and suggest that greater equality and less rigid parenting is beneficial after divorce (Stewart et al., 1997).

Link to Learning

For more information on how to help children adjust, here is guide from the American Academy of Pediatrics on Helping Children and Families Deal with Divorce.

For advice to parents, here is a set of informal recommendations.

Divorce in Middle and Older Adulthood

Livingston (2014) found that 27% of adults age 45 to 54 were divorced (see Figure 8.32). Additionally, 57% of divorced adults were women. This reflects the fact that men are more likely to remarry than are women. Two-thirds of divorces are initiated by women (AARP, 2009). Most divorces take place within the first 5 to 10 years of marriage. This time line reflects people’s initial attempts to salvage the relationship. After a few years of limited success, the couple may decide to end the marriage. It used to be that divorce after having been married for 20 or more years was rare, but in recent years the divorce rate among more long-term marriages has been increasing. Brown and Lin (2013) note that while the divorce rate in the U.S. has declined since the 1990s, the rate among those 50 and older has doubled.

Older adults are divorcing at higher rates than in prior generations. However, adults age 65 and over are still less likely to divorce than middle-aged and young adults (Wu & Schimmele, 2007). Divorce poses a number of challenges for older adults, especially women, who are more likely to experience financial difficulties and are more likely to remain single than are older men (McDonald & Robb, 2004). However, in both America (Lin, 2008) and England (Glaser et al., 2008), studies have found that the adult children of divorcing parents offer more support and care to their mothers than their fathers. While divorced, older men may be better off financially and are more likely to find another partner, so they may receive less support from their adult children.

They suggest several reasons for the “graying of divorce”. There is less stigma attached to divorce today than in the past. Some older women are out-earning their spouses, and thus may be more financially capable of supporting themselves, especially as most of their children have grown. Finally, given increases in human longevity, the prospect of living several more years or decades with an incompatible spouse may prompt middle-aged and older adults to leave the marriage. Gottman and Levenson (2000) found that divorces in early adulthood were angrier and more conflictual, with each partner blaming the other for the failures in the marriage. In contrast, they found that at midlife divorces tended to be more about having grown apart, or a cooling off of the relationship.

A survey by AARP (2009) found that men and women had diverse motivations for getting a divorce. Women reported concerns about the verbal and physical abusiveness of their partner (23%), drug/alcohol abuse (18%), and infidelity (17%). In contrast, men mentioned they had simply fallen out of love (17%), no longer shared interests or values (14%), and infidelity (14%). Both genders felt their marriage had been over long before the decision to divorce was made, with many of the middle-aged adults in the survey reporting that they stayed together because they were still raising children. Females also indicated that they remained in their marriage due to financial concerns, including the loss of health care (Sohn, 2015). However, only 1 in 4 adults regretted their decision to divorce.

The effects of divorce are varied. Overall, young adults struggle more with the consequences of divorce than do those at midlife, as they have a higher risk of depression or other signs of problems with psychological adjustment (Birditt & Antonucci, 2013). Divorce at midlife is more stressful for women. In the AARP (2009) survey, 44% of middle-aged women mentioned financial problems after divorcing their spouse; in comparison, only 11% of men reported such difficulties. However, a number of women who divorce in midlife report that they felt a great release from their day-to-day sense of unhappiness. Hetherington and Kelly (2002) found that among the divorce enhancers, those who had used the experience to better themselves and seek more productive intimate relationships, and the competent loners, those who used their divorce experience to grow emotionally, but who choose to stay single, the overwhelming majority were women.

Dating Post-Divorce

Most divorced adults have dated by one year after filing for divorce (Anderson et al., 2004; Anderson & Greene, 2011). One in four recent filers report having been in or were currently in a serious relationship, and over half were in a serious relationship by one year after filing for divorce. Not surprisingly, younger adults were more likely to be dating than were middle aged or older adults, no doubt due to the larger pool of potential partners from which they could to draw. Of course, these relationships will not all end in marriage. Teachman (2008) found that more than two thirds of women under the age of 45 had cohabited with a partner between their first and second marriages.

Dating for adults with children can be more of a challenge. Courtships are shorter in remarriage than in first marriages. When couples are “dating”, there is less going out and more time spent in activities at home or with the children. So, the couple gets less time together to focus on their relationship. Anxiety or memories of past relationships can also get in the way. As one Talmudic scholar suggests “when a divorced man marries a divorced woman, four go to bed” (Secombe & Warner, 2004).

Post-divorce parents gatekeep, that is, they regulate the flow of information about their new romantic partner to their children, in an attempt to balance their own needs for romance with consideration regarding the needs and reactions of their children. Anderson et al. (2004) found that almost half (47%) of dating parents gradually introduce their children to their dating partner, giving both their romantic partner and children time to adjust and get to know each other. Many parents who use this approach do so to protect their children from having to keep meeting someone new until it becomes clear that this relationship might be a lasting one. It might also help if the adult relationship is on firmer ground so it can weather any initial push back from children when it is revealed. Forty percent of people are open and transparent with their children about the new relationship right from the outset. Thirteen percent do not reveal the relationship until it is clear that cohabitation and or remarriage is likely. Anderson and colleagues suggest that practical matters influence which gatekeeping method parents may use. Parents may be able to successfully shield their children from a parade of partners if there is reliable childcare available. The age and temperament of the child, along with concerns about the reaction of the ex-spouse, may also influence when parents reveal their romantic relationships to their children.

Rates of re-marriage

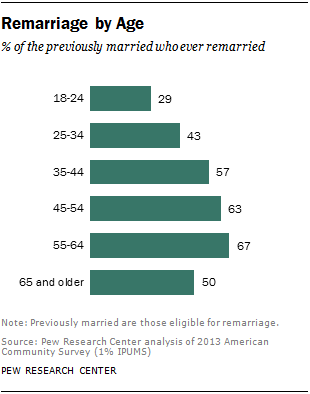

The rate for remarriage, like the rate for marriage, has been declining overall. In 2013 the remarriage rate was approximately 28 per 1,000 adults 18 and older. This represents a 44% decline since 1990 and a 16% decline since 2008 (Payne, 2015). Brown and Lin (2013) found that the rate of remarriage dropped more for younger adults than middle aged and older adults, and Livingston (2014) found that as we age, we are more likely to have remarried (see Figure 18.20). This is not surprising as it takes some time to marry, divorce, and then find someone else to marry. However, Livingston found that unlike those younger than 55, those 55 and up are remarrying at a higher rate than in the past. In 2013, 67% of adults 55-64 and 50% of adults 65 and older had remarried, up from 55% and 34% in 1960, respectively.

Men have a higher rate of remarriage at every age group starting at age 25 (Payne, 2015). Livingston (2014) reported that in 2013, 64% of divorced or widowed men compared with 52% of divorced or widowed women had remarried. However, this gender gap has narrowed over time. Even though more men still remarry, they are remarrying at a slower rate. In contrast, women are remarrying today more than they did in 1980. This gender gap has closed mostly among young and middle-aged adults, but still persists among those 65 and older.

In 2012, whites who were previously married were more likely to remarry than were other racial and ethnic groups (Livingston, 2014). Moreover, the rate of remarriage has increased among whites, while the rate of remarriage has declined for other racial and ethnic groups. This increase is driven by white women, whose rate of remarriage has increased, while the rate for white males has declined.

Success of Re-marriage

Research is mixed as to the happiness and success of remarriages. While some remarriages are more successful, especially if the divorce motivated the adult to engage in self-improvement and personal growth (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002), a number of divorced adults end up in very similar marriages the second or third time around (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). Remarriages have challenges not found in first marriages and they can create additional stress in the marital relationship.

There can also be a general lack of clarity in family roles and expectations when trying to incorporate new kin into the family structure. Even determining the appropriate terms for these kin, along with their roles, can be a challenge. Partners may have to carefully navigate their role when dealing with their partners’ children. All of this may lead to greater dissatisfaction and even resentment among family members. Even though remarried couples tend to have more realistic expectations for marriage, they tend to be less willing to stay in unhappy situations. The rate of divorce among remarriages is higher than among first marriages (Payne, 2015), which can add additional burdens, especially when children are involved.

Children’s Influence on Re-partnering

Do children affect whether a parent remarries? Goldscheider and Sassler (2006) found children residing with their mothers reduces the mothers’ likelihood of marriage, only with respect to marrying a man without children. Further, having children in the home appears to increase single men’s likelihood of marrying a woman with children (Stewart et al., 2003). There is also some evidence that individuals who participated in a stepfamily while growing up may feel better prepared for stepfamily living as adults. Goldscheider and Kaufman (2006) found that having experienced family divorce as a child is associated with a greater willingness to marry a partner with children.

When children are present after divorce, one of the challenges the adults encounter is how much influence the child will have in the selection a new partner. Greene et al. (2003) identified two types of parents. The child-focused parent allows the child’s views, reactions, and needs to influence the repartnering. In contrast, the adult-focused parent expects that their child can adapt and should accommodate to parental wishes. Anderson and Greene (2011) found that divorced custodial mothers identified as more adult focused tended to be older, more educated, employed, and more likely to have been married longer. Additionally, adult-focused mothers reported having less rapport with their children, spent less time in joint activities with their children, and the child reported lower rapport with their mothers. Lastly, when the child and partner were resisting one another, adult-focused mothers responded more to the concerns of the partner, while the child-focused mothers responded more to the concerns of the child. Understanding the implications of these two differing perspectives can assist parents in their attempts to repartner.

Is cohabitation and remarriage more difficult than divorce for children?

The remarriage of a parent may be a more difficult adjustment for a child than the divorce of a parent (Seccombe & Warner, 2004). Parents and children typically have different ideas about how the stepparent should behave. Parents and stepparents are more likely to see the stepparent’s role as that of parent. A more democratic style of parenting may become more authoritarian after a parent remarries. Biological parents are more likely to continue to be involved with their children jointly when neither parent has remarried. They are least likely to jointly be involved if the father has remarried and the mother has not. Cohabitation can be difficult for children to adjust to because cohabiting relationships in the United States tend to be short-lived. About 50 percent last less than 2 years (Brown, 2000). A child who starts a relationship with the parent’s live-in partner may have to sever this relationship later. Even in long-term cohabiting relationships, once it is over, continued contact with the child is rare.

Blended Families

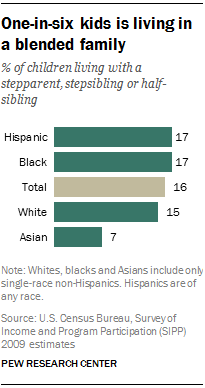

One in six children (16%) live in a blended family (Pew Research Center, 2015). As can be seen in Figure 18.24, Hispanic, black and white children are equally likely to be living in blended families. In contrast, children of Asian descent are more likely to be living with two married parents, often in their first marriage. Blended families are not new. In the 1700-1800s there were many blended families, but they were created because one parent (usually the mother) died and the other parent remarried. Most blended families today are a result of divorce and remarriage, and such origins lead to new considerations. Blended families are different from intact families and more complex in a number of ways that can pose unique challenges to those who seek to form successful blended family relationships (Visher & Visher, 1985). Children may be a part of two households, and if each has different rules, the situation can be confusing.

Members in blended families may not be as sure that others care and may require more demonstrations of affection for reassurance. For example, stepparents expect more gratitude and acknowledgment from the stepchild than they would with a biological child. Stepchildren experience more uncertainty/insecurity in their relationship with the parent and fear the parents will see them as sources of tension. Stepparents may feel guilty for a lack of feelings they may initially have toward their partner’s children. Children who are required to respond to the parent’s new mate as though they were the child’s “real” parent often react with hostility, rebellion, or withdrawal. This occurs especially if there has not been sufficient time for the relationship to develop organically.

Try It

References (Click to expand)

AARP. (2009). The divorce experience: A study of divorce at midlife and beyond. Washington, DC: AARP

Anderson, J. (2018). The impact of family structure on the health of children: Effects of divorce. The Linacre Quarterly 81(4), 378–387.

Anderson, E. R., & Greene, S. M. (2011). “My child and I are a package deal”: Balancing adult and child concerns in repartnering after divorce. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(5), 741-750.

Anderson, E.R., Greene, S.M., Walker, L., Malerba, C.A., Forgatch, M.S., & DeGarmo, D.S. (2004). Ready to take a chance again: Transitions into dating among divorced parents. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 40, 61-75.

Arditti, J. A. (1999). Rethinking relationships between divorced mothers and their children: Capitalizing on family strengths. Family Relations, 48, 109-119.

Arkowicz, H., & Lilienfeld. (2013). Is divorce bad for children? Scientific American Mind, 24(1), 68-69.

Birditt, K. S., & Antonucci, T.C. (2012). Till death do us part: Contexts and implications of marriage, divorce, and remarriage across adulthood. Research in Human Development, 9(2), 103-105.

Brown, S. L. (2000). Union transitions among cohabitors: The significance of relationship assessments and expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 833-846.

Brown, S. L., & Lin, I. (2013). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle aged and older adults 1990-2010. National Center for Family & Marriage Research Working Paper Series. Bowling Green State University. https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and- sciences/NCFMR/ documents/Lin/The-Gray-Divorce.pdf

Drexler, P. (2005). Raising boys without men. Emmaus, PA: Rodale.

Furstenberg, F. F., & Cherlin, A. J. (1991). Divided families: What happens to children when parents part. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Glaser, K., Stuchbury, R., Tomassini, C., & Askham, J. (2008). The long-term consequences of partnership dissolution for support in later life in the Unites Kingdom. Ageing & Society, 28(3), 329-351.

Goldscheider, F., & Kaufman, G. (2006). Willingness to stepparent: Attitudes about partners who already have children. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 1415 – 1436.

Goldscheider, F., & Sassler, S. (2006). Creating stepfamilies: Integrating children into the study of union formation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 275 – 291.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (2000). The timing of divorce: Predicting when a couple will divorce over a 14-year period. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 62, 737-745.

Greene, S. M., Anderson, E. R., Hetherington, E., Forgtch, M. S., & DeGarmo, D. S. (2003). Risk and resilience after divorce. In F. Walsh (Ed.), Normal family processes: Growing diversity and complexity (3rd ed., pp. 96-120). New York: Guilford Press.

Guttmann, J. (1993). Divorce in psychosocial perspective: Theory and research. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Hetherington, E. M., & Kelly, J. (2002). For better or for worse: Divorce reconsidered. New York: W.W. Norton.

Lin, I. F. (2008). Consequences of parental divorce for adult children’s support of their frail parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(1), 113-128.

Livingston, G. (2014). Four in ten couples are saying I do again. In Chapter 3. The differing demographic profiles of first-time marries, remarried and divorced adults. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/11/14/chapter-3-the-differing-demographic-profiles-of-first-time-married-remarried-and-divorced-adults/

Livingston, G. (2018). About one-third of U.S. children are living with an unmarried parent. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/27/about-one-third-of-u-s-children-are-living-with-an-unmarried-parent/

Lyngstad, T. H., & Jalovaara, M. (2010). A review of the antecedents of union dissolution. Demographic research, 23, 257-292.

McDonald, L., & Robb, A. L. (2004). The economic legacy of divorce and separation for women in old age. Canadian Journal on Aging, 23, 83-97.

McLanahan, S., & Sandefur, G. D. (1994). Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Payne, K. K. (2015). The remarriage rate: Geographic variation, 2013. National Center for Family & Marriage Research. Retrieved from http://bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/payne-remarriage-rate-fp-15-08.html

Pew Research Center. (2010). New family types. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/11/18/vi-new-family-types/

Pew Research Center. (2015). Parenting in America. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/12/2015-12-17_parenting-in-america_FINAL.pdf

Richter, D, & Lemola, S. (2017). Growing up with a single mother and life satisfaction in adulthood: A test of mediating and moderating factors. PLOS ONE 12(6): e0179639. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0179639

Seccombe, K., & Warner, R. L. (2004). Marriages and families: Relationships in social context. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Sohn, H. (2015). Health insurance and divorce: Does having your own insurance matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 982-995.

Stewart, A. J., Copeland, Chester, Malley, & Barenbaum. (1997). Separating together: How divorce transforms families. New York: Guilford Press.

Stewart, S. D., Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2003). Union formation among men in the US: Does having prior children matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 90 – 104.

Teachman, J. (2008). Complex life course patterns and the risk of divorce in second marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 294 – 305.

Temke, Mary W. 2006. “The Effects of Divorce on Children.” Durham: University of New Hampshire. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

Visher, E. B., & Visher, J. S. (1985). Stepfamilies are different. Journal of Family Therapy, 7(1), 9-18.

Weaver, J. M., & Schofield, T. J. (2015). Mediation and moderation of divorce effects on children’s behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(1), 39-48. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/fam0000043

Wu, Z., & Schimmele, C. M. (2007). Uncoupling in late life. Generations, 31(3), 41-46.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

CC Licensed Content, Shared Previously

- “Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0

- Introduction to Sociology 2e by Rice University is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License.

- Additional written material by Ellen Skinner, Portland State University is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

- Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology. Authored by: Laura Overstreet. Located at: http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- The Family. Authored by: Joel A. Muraco . Provided by: University of Wisconsin, Green Bay. Located at: https://nobaproject.com/modules/the-family. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Divorce and Remarriage. Authored by Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/chapter/relationships/. License: CC BY: Attribution

Media Attribution

- FT_18.04.11_UnmarriedParents © Pew Research Center – Click for image reuse policy

- ST_2014-11-14_remarriage-06 © Pew Research Center is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- anthony-tran-rvdlDB1D68c-unsplash © Anthony Tran is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- jude-beck-a-nWU0o73r4-unsplash © Jude Beck is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- 7301109548_85824d740b_w © moodboard is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- ST_2015-12-17_parenting-14 © Pew Research Center – Click for image reuse policy