17.4 Romantic Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Describe some of the factors related to attraction in relationships

- Apply Sternberg’s theory of love to relationships

Adolescence

Romantic Relationships

Adolescence is the developmental period during which romantic relationships typically first emerge. By the end of adolescence, most American teens have had at least one romantic relationship (Dolgin, 2011). However, culture does play a role as Asian Americans and Latinas are less likely to date than other ethnic groups (Connolly et al., 2004). Dating serves many purposes for teens, including having fun, companionship, status, socialization, sexual experimentation, intimacy, and (for those in late adolescence) partner selection (Dolgin, 2011).

There are several stages in the dating process beginning with engaging in mixed-sex group activities in early adolescence (Dolgin, 2011). The same-sex peer groups that were common during childhood expand into mixed-sex peer groups that are more characteristic of adolescence. Romantic relationships often form in the context of these mixed-sex peer groups (Connolly et al., 2000). Interacting in mixed-sex groups is easier for teens as they are among a supportive group of friends, can observe others interacting, and are kept safe from a too early intimate relationship. By middle adolescence teens are engaging in brief, casual dating or in group dating with established couples (Dolgin, 2011). Then in late adolescence dating involves exclusive, intense relationships. These relationships tend to be long-lasting and continue for a year or longer, however, they may also interfere with friendships. Although romantic relationships during adolescence are often short-lived rather than long-term committed partnerships, their importance should not be minimized. Adolescents spend a great deal of time focused on romantic relationships, and their positive and negative emotions are tied more to romantic relationships, or lack thereof, than to friendships, family relationships, or school (Furman & Shaffer, 2003). Romantic relationships contribute to adolescents’ identity formation, changes in family and peer relationships, and emotional and behavioral adjustment.

Furthermore, romantic relationships are centrally connected to adolescents’ emerging sexuality. Parents, policymakers, and researchers have devoted a great deal of attention to adolescent sexuality, in large part because of concerns related to sexual intercourse, sexually-transmitted diseases, contraception, and preventing teen pregnancies. However, sexuality involves more than this narrow focus. For example, adolescence is often the time when individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender come to recognize themselves as such (Russel et al., 2009). Thus, romantic relationships are a domain in which adolescents experiment with new behaviors and identities.

However, a negative dating relationship can adversely affect an adolescent’s development. Soller (2014) explored the link between relationship inauthenticity and mental health. Relationship inauthenticity refers to an incongruence between thoughts/feelings and actions within a relationship. Desires to gain partner approval and demands in the relationship may negatively affect an adolescent’s sense of authenticity. Because of the high status our society places on romantic relationships, especially for girls, adolescents sometimes allow themselves to be pressured into behaviors with which they are not really comfortable, and experience tension between their desires to be in a relationship and their need to set boundaries in the face of their partner’s wishes or demands. Soller found that relationship inauthenticity was positively correlated with poor mental health, including depression, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, especially for females.

Beginning Close Romantic Relationships: Factors influencing Attraction

Because most of us enter into a close romantic relationship at some point, it is useful to know what psychologists have learned about the principles of liking and loving. A major interest of psychologists is the study of interpersonal attraction, or what makes people like, and even love, each other.

Proximity

One important factor in initiating relationships is proximity, or the extent to which people are physically near us. Research has found that we are more likely to develop friendships with people who are nearby, for instance, those who live in the same dorm that we do, and even with people who just happen to sit nearer to us in our classes (Back et al., 2008).

Proximity has its effect on liking through the principle of mere exposure, which is the tendency to prefer stimuli (including, but not limited to people) that we have seen more frequently. The effect of mere exposure is powerful and occurs in a wide variety of situations. Infants tend to smile at a photograph of someone they have seen before more than they smile at a photograph of someone they are seeing for the first time (Brooks-Gunn & Lewis, 1981), and people prefer side-to-side reversed images of their own faces over their normal (nonreversed) face, whereas their friends prefer their normal face over the reversed one (Mita et al., 1977). This is expected on the basis of mere exposure, since people see their own faces primarily in mirrors, and thus are exposed to the reversed face more often.

Mere exposure may well have an evolutionary basis. We have an initial fear of the unknown, but as things become familiar, they seem more similar and safer, and thus produce more positive affect and seem less threatening and dangerous (Harmon-Jones & Allen, 2001; Freitas et al., 2005). When the stimuli are people, there may well be an added effect. Familiar people become more likely to be seen as part of the ingroup rather than the outgroup, and this may lead us to like them more. Zebrowitz and her colleagues (2007) found that we like people of our own race in part because they are perceived as similar to us.

Similarity

An important determinant of attraction is a perceived similarity in values and beliefs between the partners (Davis & Rusbult, 2001). Similarity is important for relationships because it is more convenient if both partners like the same activities and because similarity supports one’s values. We can feel better about ourselves and our choice of activities if we see that our partner also enjoys doing the same things that we do. Having others like and believe in the same things we do makes us feel validated in our beliefs. This is referred to as consensual validation and is an important aspect of why we are attracted to others.

Self-Disclosure

Liking is also enhanced by self-disclosure, the tendency to communicate frequently, without fear of reprisal, and in an accepting and empathetic manner. Friends are friends because we can talk to them openly about our needs and goals and because they listen and respond to our needs (Reis & Aron, 2008). However, self-disclosure must be balanced. If we open up about our concerns that are important to us, we expect our partner to do the same in return. If the self-disclosure is not reciprocal, the relationship may not last.

Love

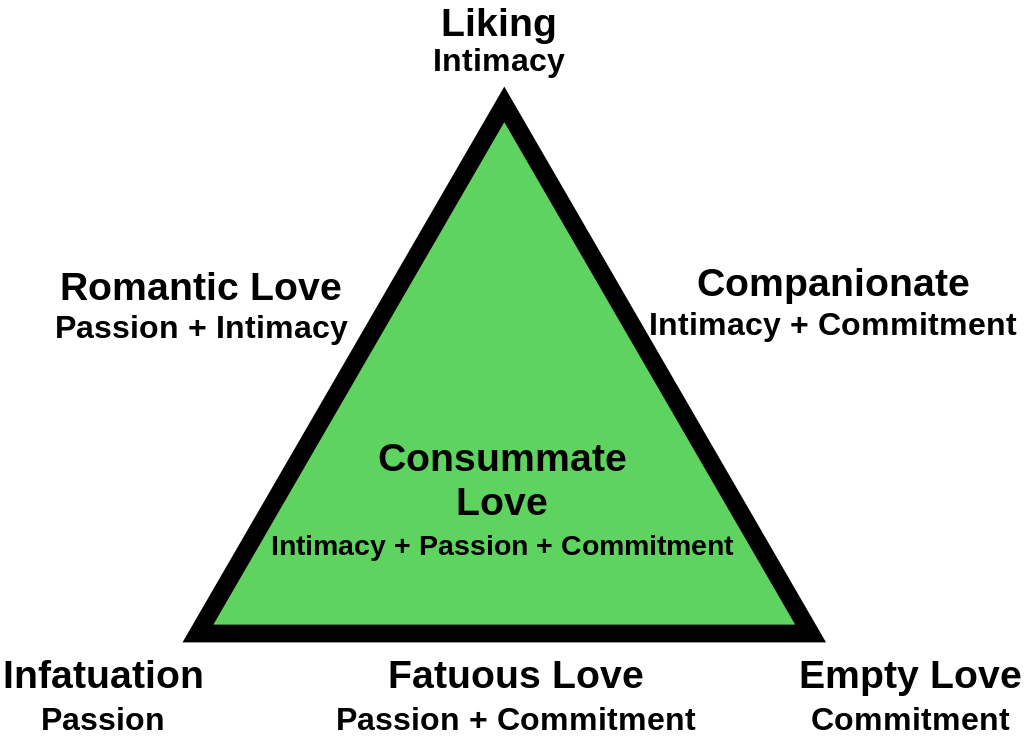

Philosophers and poets have wondered about the nature of love for centuries, and psychologists have also theorized about definitions, components, and kinds of love. Sternberg (1988) suggests that there are three main components of love: Passion, intimacy, and commitment (see figure, below). Love relationships vary depending on the presence or absence of each of these components. Passion refers to the intense, physical attraction partners feel toward one another. Intimacy involves the ability the share feelings, psychological closeness and personal thoughts with the other. Commitment is the conscious decision to stay together. Passion can be found in the early stages of a relationship, but intimacy takes time to develop because it is based on knowledge of and sharing with the partner. Once intimacy has been established, partners may resolve to stay in the relationship. Although many would agree that all three components are important to a relationship, many love relationships do not consist of all three. Let’s look at other possibilities.

Liking

In this kind of relationship, intimacy or knowledge of the other and a sense of closeness is present. Passion and commitment, however, are not. Partners feel free to be themselves and disclose personal information. They may feel that the other person knows them well and can be honest with them and let them know if they think the person is wrong. These partners are friends. However, being told that your partner “thinks of you as a friend” can be a painful blow if you are attracted to them and seeking a romantic involvement.

Infatuation

Perhaps, this is Sternberg’s version of “love at first sight” or what adolescents would call a “crush.” Infatuation consists of an immediate, intense physical attraction to someone. A person who is infatuated finds it hard to think of anything but the other person. Brief encounters are played over and over in one’s head; it may be difficult to eat and there may be a rather constant state of arousal. Infatuation is typically short-lived, however, lasting perhaps only a matter of months or as long as a year or so. It tends to be based on physical attraction and an image of what one “thinks” the other is all about.

Fatuous Love

However, some people who have a strong physical attraction push for commitment early in the relationship. Passion and commitment are aspects of fatuous love. There is no intimacy and the commitment is premature. Partners rarely talk seriously or share their ideas. They focus on their intense physical attraction and yet one, or both, is also talking of making a lasting commitment. Sometimes insistence on premature commitment follows from a sense of insecurity and a desire to make sure the partner is locked into the relationship.

Empty Love

This type of love may be found later in a relationship or in a relationship that was formed to meet needs other than intimacy or passion, including financial needs, childrearing assistance, or attaining/maintaining status. Here the partners are committed to staying in the relationship for the children, because of a religious conviction, or because there are no alternatives. However, they do not share ideas or feelings with each other and have no (or no longer any) physical attraction for one another.

Romantic Love

Intimacy and passion are components of romantic love, but there is no commitment. The partners spend much time with one another and enjoy their closeness, but have not made plans to continue. This may be true because they are not in a position to make such commitments or because they are looking for passion and closeness and are afraid it will die out if they commit to one another and start to focus on other kinds of obligations.

Companionate Love

Intimacy and commitment are the hallmarks of companionate love. Partners love and respect one-another and they are committed to staying together. However, their physical attraction may have never been strong or may have just died out over time. Nevertheless, partners are good friends and committed to one another.

Consummate Love

Intimacy, passion, and commitment are present in consummate love. This is often perceived by western cultures as “the ideal” type of love. The couple shares passion; the spark has not died, and the closeness is there. They feel like best friends, as well as lovers, and they are committed to staying together.

Try It

Relationships 101: Predictors of Marital Harmony

Advice on how to improve one’s marriage is centuries old. One of today’s experts on marital communication is John Gottman. Gottman (1999) differs from many marriage counselors in his belief that having a good marriage does not depend on compatibility. Rather, he argues that the way partners communicate with one another is crucial. At the University of Washington in Seattle, Gottman has conducted some of the most thorough and interesting studies of marital relationships. His research team measured the physiological responses of thousands of couples as they discuss issues of disagreement. Fidgeting in one’s chair, leaning closer to or further away from the partner while speaking, and increases in respiration and heart rate are all recorded and analyzed along with videotaped recordings of the partners’ exchanges. Gottman is trying to identify aspects of communication patterns that can accurately predict whether or not a couple will stay together. In marriages destined to fail, partners engage in the “marriage killers”: Contempt, criticism, defensiveness, and stonewalling. Each of these undermines the caring and respect that healthy marriages require. To some extent, all partnerships include some of these behaviors occasionally, but when these behaviors become the norm, they can signal that the end of the relationships is near; for that reason, they are known as “Gottman’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse”. Contempt, which it entails mocking or derision and communicates the other partner is inferior, is seen of the worst of the four because it is the strongest predictor of divorce. (Click here for a suggestions on diffusing your own contempt.)

Gottman et al. (2000) researched the perceptions newlyweds had about their partner and marriage. The Oral History Interview used in this study, which looks at eight variables in marriage including: Fondness/affection, we-ness, expansiveness/ expressiveness, negativity, disappointment, and three aspects of conflict resolution (chaos, volatility, glorifying the struggle), was able to predict the stability of the marriage (vs. divorce) with 87% accuracy at the four to six year-point and 81% accuracy at the seven to nine year-point. Gottman (1999) developed workshops for couples to strengthen their marriages based on the results of the Oral History Interview. Interventions include increasing positive regard for each other, strengthening their friendship, and improving communication and conflict resolution patterns.

Accumulated Positive Deposits to the “Emotional Bank Account”

When there is a positive balance of relationship deposits this can help the overall relationship in times of conflict. For instance, some research indicates that a husband’s level of enthusiasm in everyday marital interactions was related to a wife’s affection in the midst of conflict (Driver & Gottman, 2004), showing that being friendly and making deposits can change the nature of conflict. Gottman and Levenson (1992) also found that couples rated as having more pleasant interactions, compared with couples with less pleasant interactions, reported higher marital satisfaction, less severe marital problems, better physical health, and less risk for divorce. Finally, Janicki et al. (2006) showed that the intensity of conflict with a spouse predicted marital satisfaction, unless there was a record of positive partner interactions, in which case the conflict did not matter as much. Again, it seems as though having a positive balance through prior positive deposits helps to keep relationships strong even in the midst of conflict.

Link to Learning

Many additional techniques for maintaining healthy relationships, such as building love maps, turning towards our partner’s “bids” for affection and attention, managing conflict, and changing how we interpret conflict, can be found on the Gottman Institute Website.

References (Click to expand)

Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2008). Becoming friends by chance. Psychological Science, 19(5), 439–440.

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Lewis, M. (1981). Infant social perception: Responses to pictures of parents and strangers. Developmental Psychology, 17(5), 647–649.

Connolly, J., Craig, W., Goldberg, A., & Pepler, D. (2004). Mixed-gender groups, dating, and romantic relationships in early adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 14, 185-207.

Connolly, J., Furman, W., & Konarski, R. (2000). The role of peers in the emergence of heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescence. Child Development, 71, 1395–1408.

Davis, J. L., & Rusbult, C. E. (2001). Attitude alignment in close relationships. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 81(1), 65–84.

Dolgin, K. G. (2011). The adolescent: Development, relationships, and culture (13th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Driver, J., & Gottman, J. (2004). Daily marital interactions and positive affect during marital conflict among newlywed couples. Family Process, 43, 301–314.

Freitas, A. L., Azizian, A., Travers, S., & Berry, S. A. (2005). The evaluative connotation of processing fluency: Inherently positive or moderated by motivational context? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(6), 636–644.

Furman, W., & Shaffer, L. (2003). The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 3–22). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gottman, J. M. (1999). Couple’s handbook: Marriage Survival Kit Couple’s Workshop. Seattle, WA: Gottman Institute.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 221–233.

Gottman, J. M., Carrere, S., Buehlman, K. T., Coan, J. A., & Ruckstuhl, L. (2000). Predicting marital stability and divorce in newlywed couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 14(1), 42-58.

Harmon-Jones, E., & Allen, J. J. B. (2001). The role of affect in the mere exposure effect: Evidence from psychophysiological and individual differences approaches. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(7), 889–898.

Janicki, D., Kamarck, T., Shiffman, S., & Gwaltney, C. (2006). Application of ecological momentary assessment to the study of marital adjustment and social interactions during daily life. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 168–172.

Mita, T. H., Dermer, M., & Knight, J. (1977). Reversed facial images and the mere-exposure hypothesis. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 35(8), 597–601.

Reis, H. T., & Aron, A. (2008). Love: What is it, why does it matter, and how does it operate? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(1), 80–86.

Russell, S. T., Clarke, T. J., & Clary, J. (2009). Are teens “post-gay”? Contemporary adolescents’ sexual identity labels. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 884–890.

Soller, B. (2014). Caught in a bad romance: Adolescent romantic relationships and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55(1), 56-72.

Sternberg, R. (1988). A triangular theory of love. Basic.

Zebrowitz, L. A., Bronstad, P. M., & Lee, H. K. (2007). The contribution of face familiarity to in group favoritism and stereotyping. Social Cognition, 25(2), 306–338.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

OER Attributions

- “Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0/modified and adapted by Dan Grimes & Ellen Skinner, Portland State University

- Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License/modified and adapted by Dan Grimes & Ellen Skinner, Portland State University

- Additional written materials by Dan Grimes & Brandy Brennan, Portland State University and are licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0

- Love, Friendship, and Social Support by Debi Brannan and Cynthia D. Mohr is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- Additional written material by Ellen Skinner & Heather Brule, Portland State University is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Media Attributions

- 640px-YoungCoupleEmbracing-20070508 © Kelley Boone is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 1024px-Triangular_Theory_of_Love.svg © Lnesa is licensed under a Public Domain license