10.1 Piaget’s Sensorimotor and Preoperational Stages

Learning Objectives

- Explain the Piagetian concepts of schema, assimilation, and accommodation.

- List and describe the six substages of sensorimotor intelligence.

- Describe Piaget’s preoperational stage of development

- Illustrate limitations in early childhood thinking, including animism, egocentrism, and conservation errors

Piaget and the Sensorimotor Stage

Piaget believed that children, even infants, actively try to make sense of their environments. He viewed intelligence, not as knowledge or facts we acquire, but as the processes through which we adapt to our environment. He argued that differences between children and adults are not based on the fact that children know less than adults, but because they think in different ways the adults do. Piaget used the clinical method in which he closely observed individual children in great detail over long periods of time in their natural environment. From these observations he developed his theory of cognitive development, which posits four qualitatively different stages (Piaget, 1954).

Schema, assimilation and accommodation

In addition to descriptions of different stages, Piaget was also very interested in the processes by which people come to understand the world (and in the process, to understand themselves). He was focused on universal physical properties of environments, like time, space, and causality, which he called logic-mathematical thought. He argued that people make sense of the world by interacting with it. He assumed that all people, even infants, are active, curious, energetic, and intrinsically motivated, and it is through their active attempts to “make things happen” that they learn about natural laws. Piaget held that, as they go, infants and children construct models of how the world works, which are partial, incomplete, and not totally correct. He called these models, schema, which an be thought of as frameworks for organizing information. As we continue interacting with the world, we keep trying out our mental models, and eventually encounter experiences that contradict them. These contradictions allow us to revise our models so that they can better account for the interactions we are experiencing. As models are revised, they are more adaptive– meaning that they guide our actions more effectively as we try to reach our goals.

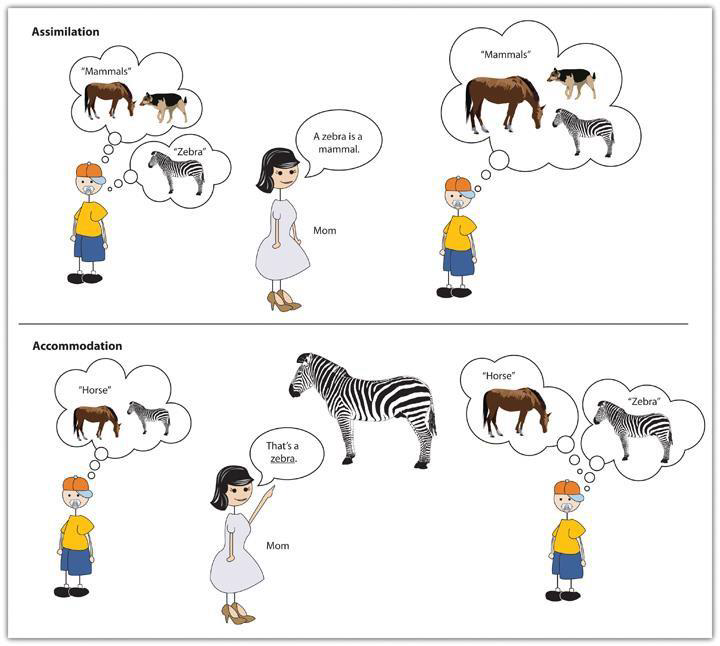

Children develop their models, that is, their schemata, through processes of assimilation and accommodation. When faced with something new, a child may demonstrate assimilation, which is fitting the new information into an existing schema, such as calling all animals with four legs “doggies” because he or she has the concept of doggie. When it becomes clear that the new information no longer fits into the old schema, instead of assimilating the information, the child may demonstrate accommodation, which is expanding the framework of knowledge to accommodate the new situation and thus learning a new concept to more accurately name the animal. For example, recognizing that a horse is different than a zebra means the child has accommodated, and now the child has both a zebra schema and a horse schema. Even as adults we continue to try and “make sense” of new situations by determining whether they fit into our old way of thinking (assimilation) or whether we need to modify our thoughts (accommodation).

Piaget also described a process of organization, in which we combine existing schemes into new and more complex ones. By grouping and re-arranging schemas, and connecting them together, we can grow and refine our knowledge structures. Finally, he pointed to the process of disequilibration, where we detect discrepancies or contradictions between the models we are constructing and the experiences we are having in our interactions with the world. These contradictions can produce confusion or frustration, but they are developmentally helpful, because they lead to attempts to readjust actions and models so they are in better alignment, though a process called equilibration. Disequilibration and equilibration can also be applied to models themselves, as we detect that sub-parts of models contradict each other or are not in alignment. Though processes of equilibration we can re-organize models so that they are more internally consistent and coherent.

Cognitive development during infancy

Piaget’s theories revolutionized the way that developmentalists thought about infants. He was one of the first researchers to argue that infants are intelligent and they are busily constructing their own understandings of the world through their interactions with the environment. According to the Piagetian perspective, infants learn about the world primarily through their senses and motor abilities (Harris, 2005). These basic motor and sensory abilities provide the foundation for the cognitive skills that will emerge during the subsequent stages of cognitive development. The first stage of cognitive development is referred to as the sensorimotor stage and it occurs through six substages. Table 9.1 identifies the ages typically associated with each substage.

Table 9.1 Infant Ages for the Six Substages of the Sensorimotor Stage

| Substage 1 | Reflexes (0-1 month) |

| Substage 2 | Primary Circular Reactions (1–4 months) |

| Substage 3 | Secondary Circular Reactions (4–8 months) |

| Substage 4 | Coordination of Secondary Circular Reactions (8–12 months) |

| Substage 5 | Tertiary Circular Reactions (12–18 months) |

| Substage 6 | Beginning of Representational Thought (18–24 months) |

adapted from Lally & Valentine-French, 2019

Substage 1: Reflexes

Newborns learn about their world through the use of their reflexes, such as when sucking, reaching, and grasping. Eventually the use of these reflexes becomes more deliberate and purposeful.

Substage 2: Primary Circular Reactions

During these next 3 months, the infant begins to actively involve his or her own body in some form of repeated activity. An infant may accidentally engage in a behavior and find it interesting such as making a vocalization. This interest motivates the infant to try to do it again and helps the infant learn a new behavior that originally occurred by chance. The behavior is identified as circular because of the repetition, and as primary because it centers on the infant’s own body.

Substage 3: Secondary Circular Reactions

The infant begins to interact with objects in the environment. At first the infant interacts with objects (e.g., a crib mobile) accidentally, but then these contacts with the objects are deliberate and become a repeated activity. The infant becomes more and more actively engaged in the outside world and takes delight in being able to make things happen. Repeated motion brings particular interest as, for example, the infant is able to bang two lids together from the cupboard when seated on the kitchen floor.

Substage 4: Coordination of Secondary Circular Reactions

The infant combines these basic reflexes and simple behaviors and uses planning and coordination to achieve a specific goal. Now the infant can engage in behaviors that others perform and anticipate upcoming events. Perhaps because of continued maturation of the prefrontal cortex, the infant become capable of having a thought and carrying out a planned, goal-directed activity. For example, an infant sees a toy car under the kitchen table and then crawls, reaches, and grabs the toy. The infant is coordinating both internal and external activities to achieve a planned goal.

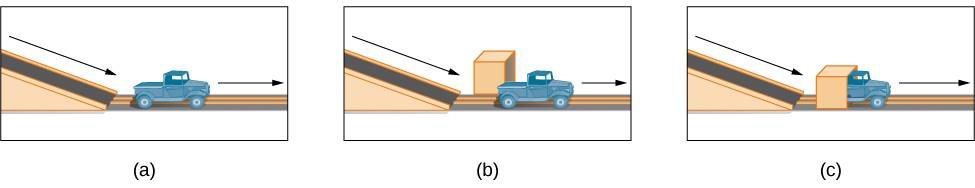

Substage 5: Tertiary Circular Reactions

The toddler is considered a “little scientist” and begins exploring the world in a trial-and-error manner, using both motor skills and planning abilities. For example, the child might throw her ball down the stairs to see what happens. The toddler’s active engagement in experimentation helps them learn about their world.

Watch It

See how even babies think like little scientists in the selected clip from this TED talk.

Substage 6: Beginning of Representational Thought

The sensorimotor period ends with the appearance of symbolic or representational thought. The toddler now has a basic understanding that objects can be used as symbols. Additionally, the child is able to solve problems using mental strategies, to remember something heard days before and repeat it, and to engage in pretend play. This initial movement from a “hands-on” approach to knowing about the world to the more mental world of substage six marks the transition to preoperational thought.

Try It

Development of object permanence

A critical milestone during the sensorimotor period is the development of object permanence. Object permanence is the understanding that even if something is out of sight, it still exists (Bogartz et al., 2000). According to Piaget, young infants cannot represent objects mentally, so they do not remember it after it has been removed from sight. Piaget studied infants’ reactions when a toy was first shown to them and then hidden under a blanket. Infants who had already developed object permanence would reach for the hidden toy, indicating that they knew it still existed, whereas infants who had not developed object permanence would appear confused. Piaget emphasizes this construct because it is an objective way for children to demonstrate how they mentally represent their world. Children have typically acquired this milestone by 8 months. Once toddlers have mastered object permanence, they enjoy games like hide and seek, and they realize that when someone leaves the room they are still in the world. Toddlers also point to pictures in books and look in appropriate places when you ask them to find objects.

In Piaget’s view, around the same time children develop object permanence, they also begin to exhibit stranger anxiety, which is a fear of unfamiliar people (Crain, 2005). Babies may demonstrate this by crying and turning away from a stranger, by clinging to a caregiver, or by attempting to reach their arms toward familiar faces, such as parents. Stranger anxiety results when a child is unable to assimilate the stranger into an existing schema; therefore, she cannot predict what her experience with that stranger will be like, which results in a fear response.

Watch It

Watch this Ted talk from Alison Gopnik to hear about more research done on cognition in babies.

You can view the transcript for “Alison Gopnik: What do babies think?” here (opens in new window).

Critique of Piaget

Piaget thought that children’s ability to understand objects, such as learning that a rattle makes a noise when shaken, was a cognitive skill that develops slowly as a child matures and interacts with the environment. Today, developmental psychologists question the timetables Piaget laid out. Researchers have found that even very young children understand objects and how they work long before they have experience with those objects (Baillargeon, 1987; Baillargeon, Li, Gertner, & Wu, 2011). For example, Piaget believed that infants did not fully master object permanence until substage 5 of the sensorimotor period (Thomas, 1979). However, infants seem to be able to recognize that objects have permanence at much younger ages. Diamond (1985) found that infants show earlier knowledge if the waiting period is shorter. At age 6 months, they retrieved the hidden object if their wait for retrieving the object is no longer than 2 seconds, and at 7 months if the wait is no longer than 4 seconds.

Watch It: Planful Problem-solving during Late Infancy

To give you a sense of what infants’ cognitive capacities allow them to do, here are some video clips of planful problem-solving at 8 months and about a year old:

Try It

Piaget’s Preoperational Stage

Building on the accomplishments of the first stage of cognitive development, which takes place during infancy and involves sensorimotor regulations, preschoolers enter the second stage of cognitive development, called the preoperational stage, which is organized around symbolic regulations. According to Piaget, this stage occurs from the age of 2 to 7 years. In the preoperational stage, children use symbols to represent words, images, and ideas, which is why children in this stage engage in pretend play. A child’s arms might become airplane wings as she zooms around the room, or a child with a stick might become a brave knight with a sword. Children also begin to use language in the preoperational stage, but they cannot understand adult logic or mentally manipulate information. The term operational refers to logical manipulation of information, so children at this stage are considered pre-operational. Children’s logic is based on their own personal knowledge of the world so far, rather than on conventional knowledge.

The preoperational period is divided into two stages:

- The symbolic function substage occurs between 2 and 4 years of age and is characterized by gains in symbolic thinking, in which the child is able to mentally represent an object that is not present, and a dependence on perception in problem solving.

- The intuitive thought substage, lasting from 4 to 7 years, is marked by greater dependence on intuitive thinking rather than just perception (Thomas, 1979). This implies that children think automatically without using evidence. At this stage, children ask many questions as they attempt to understand the world around them using immature reasoning. Let us examine some of Piaget’s assertions about children’s cognitive abilities at this age.

Pretend play

Pretending is a favorite activity at this time. A toy has qualities beyond the way it was designed to function and can now be used to stand for a character or object unlike anything originally intended. A teddy bear, for example, can be a baby or the queen of a faraway land. Piaget believed that pretend play helped children practice and solidify new schemata they were developing cognitively. This play, then, reflected changes in their conceptions or thoughts. However, children also learn as they pretend and experiment. Their play does not simply represent what they have learned (Berk, 2007).

Symbolic representation

In addition to ushering in an era of pretend play, the development of symbolic representation revolutionizes the way young children can think and act. Representational capacities underlie the emergence of language which opens up channels of communication with others and provides young children words and concepts for their inner experiences (like emotion labels). Symbolic capacities also scaffold the development of memory, and allow young children to remember and discuss autobiographical events. They become very interested in two dimensional representations, like photographs and computer screens, and can interact with grandparents and others using these tools.

As seen at the end of the sensorimotor period, toddlers begin to use primitive representations to solve problems in their heads. During the preschool years, cognitive advances allow them to get better and better at trying out strategies mentally before taking action. Hence, planning and problem-solving become central activities. Problem-solving can be used to facilitate physical play (e.g., planning how to build a castle), solve interpersonal conflicts (e.g., two children want the same toy), or figure out how to comfort oneself when one is sad.

Mental representations are also key to the advances in executive function and self-regulation described earlier. When children can hold goals in their minds that are different from the ones that spontaneously emerge, they use representations of what they are supposed to do to modulate or manage what they want to do. Young children show an outpouring of representational activities, including language, pretend play, story telling, singing, drawing, looking a photos, and discussing the past and present. They love to engage in joint problem-solving and be read to, often asking for the same book or video over and over again, pouring over and discussing the story, until they can repeat every word.

Despite the many advances that symbolic thought brings to young children, there are still several significant limitations to their thinking, including egocentrism, perceptual salience, and animism. When parents see behaviors typical of the preoperational stage, it is important that they correctly interpret their meaning. Young children are not being hard to get along with. These behaviors are the result of genuine limitations in their cognitive functioning. Young children can understand many ideas and follow rules, but for the best developmental outcomes, adults should temper their expectations and demands so that they are reasonable, and explain their thinking using language that is developmentally attuned to children’s current cognitive capacities.

Try It

Egocentrism

Egocentrism in early childhood refers to the tendency of young children not to be able to take the perspective of others, and instead the child thinks that everyone sees, thinks, and feels just as they do. Egocentric children are not able to infer the perspective of other people and instead attribute their own perspective to everyone in the situation. For example, ten-year-old Keiko’s birthday is coming up, so her mom takes 3-year-old Kenny to the toy store to choose a present for his sister. He selects an Iron Man action figure for her, thinking that if he likes the toy, his sister will too.

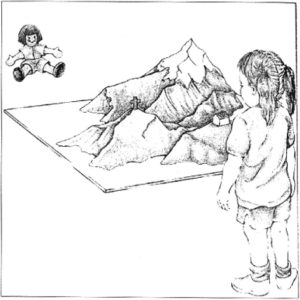

Piaget’s classic experiment on egocentrism involved showing children a three-dimensional model of a mountain and asking them to describe what a doll that is looking at the mountain from a different angle might see (see Figure 10.7). Children tend to choose a picture that represents their own, rather than the doll’s view. By age 7 children are less self-centered. However, even younger children when speaking to others tend to use different sentence structures and vocabulary when addressing a younger child or an older adult. This indicates some awareness of the views of others.

Perceptual salience

Perceptual salience means that children reason, not based on what they know, but based on what they perceive (ie.g., see and hear) in the present local context. This cognitive limitation is on display every Halloween, when parents dress up, especially if they use masks. For a preoperational child, the mask is so perceptually salient that even if the parent continues to talk and the child can recognize their voice, their experience is overwhelmed by the transformation of the parent’s face, that they react to the masked parent as if they were a stranger. At this age, children’s understanding is halfway between the reasoning based on action of the sensorimotor period and the reasoning based on logic of the concrete operational period. During the preoperational period, reasoning is based on empirical reality, that is, information provided by the senses.

Watch It

The boys in this interview display egocentrism by believing that the researcher sees the same thing as they do, even after switching positions.

This video demonstrates that older children are able to look at the mountain from different viewpoints and no longer fall prey to egocentrism.

You can view the transcript for “Piaget’s Mountains Task” here (opens in new window).

Animism

Animism refers to attributing life-like qualities to objects. The cup is alive, the chair that falls down and hits the child’s ankle is mean, and the toys need to stay home because they are tired. Cartoons frequently show objects that appear alive and take on lifelike qualities. Young children do seem to think that objects that move may be alive, but after age three, they seldom refer to objects as being alive (Berk, 2007).

Intuitive substage (age 4-7 years)

During the intuitive substage, children begin to move toward logical thinking. They show some signs of logical reasoning, but can’t explain how or why they think as they do. This is an age filled with questions, as children begin to make sense of their worlds. Parents should know that children’s ceaseless “why?” questions do not require detailed explanations. They are looking for brief and simple explanations. For example, if children ask “Why do I have to wear a helmet when I ride a bicycle?” they are not looking for a lecture on legal issues, but just a simple “To keep your head safe.” Likewise, if they come back from a bike ride and say “Well, I didn’t fall down, so now I don’t need to wear a helmet any more”, you can explain the idea of risk through an everyday example, saying, “You have to wear it every time, because you could fall down.” If you want to try a metaphor, you could explain, ” Your head is like a glass, it could get broken. Does a glass break every time you drop it? No. But does that mean that it’s a good idea to drop it? No. We want to keep your head safe.”

Centration

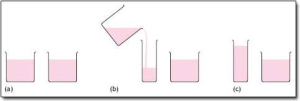

The primary limitation of thought during the intuitive substage is called centration. Centration means that understanding is dominated (i.e., centered on) a single feather– the most perceptually salient one. At this age, children cannot hold or coordinate two features of an object at the same time. Piaget demonstrated this aspect of preoperational thought in a series of experiments. They showed that young children do not yet have the logical notion of conservation, which refers to the ability to recognize that aspects like quantity remain the same, even when over transformations in appearance.

Inability to conserve

Using Kenny and Keiko again, dad gave a slice of pizza to 10-year-old Keiko and another slice to 3-year-old Kenny. Kenny’s pizza slice was cut into five pieces, so Kenny told his sister that he got more pizza than she did. Kenny did not understand that cutting the pizza into smaller pieces did not increase the overall amount. This was because Kenny exhibited centration when he focused on only one characteristic (the number of pieces) to the exclusion of others (total amount). Kenny’s reasoning was based on his five pieces of pizza compared to his sister’s one piece even though the total amount of pizza each had was the same. Keiko was able to consider several characteristics of an object than just one. Because children have not developed this understanding of conservation, they cannot perform mental operations.

The classic Piagetian experiment associated with conservation involves liquid (Crain, 2005). As seen on the left side of Figure 5.3, the child is shown two glasses which are filled to the same level and asked if they have the same amount. Usually the child agrees they have the same amount. The experimenter then pours the liquid in one glass to a taller and thinner glass (as shown in the center of Figure 10.8). The child is again asked if the two glasses have the same amount of liquid. The preoperational child will typically say the taller glass now has more liquid because it is taller (as shown on the right side). The child has centrated on the height of the glass and fails to conserve.

Classification errors

Preoperational children also demonstrate centration when they have difficulty understanding that an object can be classified in more than one way. For example, if shown three white buttons and four black buttons and asked whether there are more black buttons or buttons, the child is likely to respond that there are more black buttons. They focus on the most salient feature (black buttons) and cannot keep in mind the the general class of buttons, so they compare black versus white buttons, instead of part versus whole. Because young children lack these general classes, their reasoning is typically transductive, that is, making faulty inferences from one specific example to another. For example, Piaget’s daughter Lucienne stated she had not had her nap, therefore it was not afternoon. She did not understand that afternoons are a time period and her nap was just one of many events that occurred in the afternoon (Crain, 2005). As the child’s capacity to mentally represent and coordinate multiple features improves, the ability to classify objects emerges.

Watch It

This clip shows how younger children struggle with the concept of conservation and demonstrate irreversibility.

Critique of Piaget

Similar to the critique of the sensorimotor period, several psychologists have attempted to show that Piaget also underestimated the intellectual capabilities of the preoperational child. For example, children’s specific experiences can influence when they are able to conserve. Children of pottery makers in Mexican villages know that reshaping clay does not change the amount of clay at much younger ages than children who do not have similar experiences (Price-Williams et al., 1969). Crain (2005) also showed that under certain conditions preoperational children can think rationally about mathematical and scientific tasks, and they are not always as egocentric as Piaget implied. Research on theory of mind (discussed later in the chapter) shows that some children overcome egocentrism by 4 or 5 years of age, which is sooner than Piaget indicated. As with sensorimotor development, Piaget seemed to be right about the exact sequence and the processes involved in cognitive development, as well as when these steps are typically observable under naturalistic conditions. But current research has provided more accurate estimates of the exact ages when underlying capacities emerge, which could only be revealed by working with children in specific experimental conditions that removed barriers to their performance.

Try It

References (Click to expand)

Baillargeon, R. (1987. Object permanence in 3 ½ and 4 ½ year-old infants. Developmental Psychology, 22, 655-664.

Baillargeon, R., Li, J., Gertner, Y, & Wu, D. (2011). How do infants reason about physical events? In U. Goswami (Ed.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of childhood cognitive development. John Wiley.

Berk, L. E. (2007). Development through the life span (4th ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

Bogartz, R. S., Shinskey, J. L., & Schilling, T. (2000). Object permanence in five-and-a-half month old infants. Infancy, 1(4), 403-428.

Crain, W. (2005). Theories of development concepts and applications (5th ed.). Pearson

Diamond, A. (1985). Development of the ability to use recall to guide actions, as indicated by infants’ performance on AB. Child Development, 56, 868-883.

Harris, Y. R. (2005). Cognitive development. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human development (pp. 276-281). Sage Publications.

Piaget, J. (1954). The construction of reality in the child. Basic Books.

Price-Williams, D.R., Gordon, W., & Ramirez, M. (1969). Skill and conservation: A study of pottery making children. Developmental Psychology, 1, 769.

Thomas, R. M. (1979). Comparing theories of child development. Wadsworth.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

CC Licensed Content

- “Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development.” Authored by: Stephanie Loalada for Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/chapter/cognitive-development-2/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology. Authored by: Laura Overstreet. Located at: http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Piaget’s theory of cognitive development. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piaget%27s_theory_of_cognitive_development. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cognitive Development. Authored by: Tera Jones for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/chapter/cognitive-development/ License: CC BY: Attribution

Media Attributions

- Toddler boy. Authored by: khats cassim. Provided by: Pexels. Located at: https://www.pexels.com/photo/photo-of-toddler-1701097/. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Clapping baby. Authored by: Avraham Nacher . Provided by: Pixabay. Located at: https://pixabay.com/photos/baby-happy-clap-smile-fun-2320701/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Baillargeon © Lally & Valentine-French is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- assimilation © Lally & Valentine-French is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- girls. Provided by: Maxpixel. Located at: https://www.maxpixel.net/Smart-Student-Cute-Little-Girl-Smart-Little-Girl-2811377. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Three Mountains Task. Located at: https://c2.staticflickr.com/4/3878/14457048196_be28bebd62_b.jpg

All Rights Reserved Content

- Alison Gopnik: What do babies think?. Provided by: Ted. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cplaWsiu7Yg. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Laura Schulz: The surprisingly logical minds of babies. Provided by: Ted. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y1KIVZw7Jxk. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Piaget – Stage 2 – Preoperational – Lack of Conservation. Provided by: Fi3021’s channel. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GLj0IZFLKvg&feature=youtu.be. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Piaget – Egocentrism and Perspective Taking (Preoperational and Concrete Operational Stages). Authored by: adam. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RDJ0qJTLohM. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Piaget’s Mountains Task. Authored by: UofMNCYFC. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v4oYOjVDgo0. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License