6.2 Sleep

Learning Objectives

- Describe sleep concerns for infants

- Explain why sleep is important for adolescents.

Infant Sleep

Infants 0 to 2 years of age sleep an average of 12.8 hours a day, although this changes and develops gradually throughout an infant’s life. For the first three months, newborns sleep between 14 and 17 hours a day, then they become increasingly alert for longer periods of time. About one-half of an infant’s sleep is rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and infants often begin their sleep cycle with REM rather than non-REM sleep. They also move through the sleep cycle more quickly than adults.

Parents spend a significant amount of time worrying about and losing even more sleep over their infant’s sleep schedule, but there remains a great deal of variation in sleep patterns and habits for individual children. A 2018 study showed that at 6 months of age, 62% of infants slept at least six hours during the night, 43% of infants slept at least 8 hours through the night, and 38% of infants were not sleeping at least six continual hours through the night. At 12 months, 28% of children were still not sleeping at least 6 uninterrupted hours through the night, while 78% were sleeping at least 6 hours, and 56% were sleeping at least 8 hours.[1]

The most common infant sleep-related problem reported by parents is nighttime waking. Studies of new parents and sleep patterns show that parents lose the most sleep during the first three months with a new baby, with mothers losing about an hour of sleep each night, and fathers losing a disproportionate 13 minutes. This decline in sleep quality and quantity for adults persists until the child is about six years old. [2]

While this shows there is no precise science as to when and how an infant will sleep, there are general trends in sleep patterns. Around six months, babies typically sleep between 14-15 hours a day, with 3-4 of those hours happening during daytime naps. As they get older, these naps decrease from several to typically two naps a day between ages 9-18 months. Often, periods of rapid weight gain or changes in developmental abilities such as crawling or walking will cause changes to sleep habits as well. Infants generally move towards one 2-4 hour nap a day by around 18 months, and many children will continue to nap until around four or five years old.[3]

Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths (SUID)

Each year in the United States, there are about 3,500 Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths (SUID). These deaths occur among infants less than one-year-old and have no immediately obvious cause (Moon et al. 2016). The three commonly reported types of SUID are:

- Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS): SIDS is identified when the death of a healthy infant occurs suddenly and unexpectedly, and medical and forensic investigation findings (including an autopsy) are inconclusive. SIDS is the leading cause of death in infants up to 12 months old, and approximately 1,500 infants died of SIDS in 2013 (Moon et al. 2016). The risk of SIDS is highest at 4 to 6 weeks of age. Because SIDS is diagnosed when no other cause of death can be determined, possible causes of SIDS are regularly researched. One leading hypothesis suggests that infants who die from SIDS have abnormalities in the area of the brainstem responsible for regulating breathing (Weekes-Shackelford & Shackelford, 2005). Although the exact cause is unknown, doctors have identified the following risk factors for SIDS:

- low birth weight

- siblings who have had SIDS

- sleep apnea

- of African-American or Inuit descent

- low socioeconomic status (SES)

- smoking in the home

- Unknown cause: The sudden death of an infant less than one year of age that cannot be explained because a thorough investigation was not conducted and the cause of death could not be determined.

- Accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed: Reasons for accidental suffocation include the following: suffocation by soft bedding, another person rolling on top of or against the infant while sleeping, an infant being wedged between two objects such as a mattress and wall, and strangulation such as when an infant’s head and neck become caught between crib railings.

The combined SUID rate declined considerably following the release of the American Academy of Pediatrics safe sleep recommendations in 1992, which advocated that infants be placed on their backs for sleep (non-prone position). These recommendations were followed by a major Back to Sleep Campaign in 1994. According to the CDC, the SIDS death rate is now less than one-fourth of what is was (130 per 100,000 live birth in 1990 versus 40 in 2015). However, accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed mortality rates remained unchanged until the late 1990s. Some parents were still putting newborns to sleep on their stomachs partly because of past tradition. Most SIDS victims experience several risks, an interaction of biological and social circumstances. But thanks to research, the major risk, stomach sleeping, has been highly publicized. Other causes of death during infancy include congenital birth defects and homicide.

Co-Sleeping

The location of sleep depends primarily on the baby’s age and culture. Bed-sharing (in the parents’ bed) or co-sleeping (in the parents’ room) is the norm is some cultures, but not in others (Esposito et al. 2015) [4]. Colvin et al. (2014)[5] analyzed a total of 8,207 deaths from 24 states during 2004–2012. The deaths were documented in the National Center for the Review and Prevention of Child Deaths Case Reporting System, a database of death reports from state child death review teams. The results indicated that younger victims (0-3 months) were more likely to die by bed-sharing and sleeping in an adult’s bed or on a person. A higher percentage of older victims (4 months to 364 days) rolled into objects in the sleep environment and changed position from side/back to prone. Carpenter et al. (2013)[6] compared infants who died of SIDS with a matched control and found that infants younger than three months old who slept in bed with a parent were five times more likely to die of SIDS compared to babies who slept separately from the parents, but were still in the same room. They concluded that bed-sharing, even when the parents do not smoke or take alcohol or drugs, increases the risk of SIDS. However, when combined with parental smoking and maternal alcohol consumption and/or drug use, the risks associated with bed-sharing greatly increased.

Despite the risks noted above, the controversy about where babies should sleep has been ongoing. Co-sleeping has been recommended for those who advocate attachment parenting (Sears & Sears, 2001) [7] and other research suggests that bed-sharing and co-sleeping is becoming more popular in the United States (Colson et al., 2013) [8]. So, what are the latest recommendations?

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) actually updated their recommendations for a Safe Infant Sleeping Environment in 2016. The most recent AAP recommendations on creating a safe sleep environment include:

- Back to sleep for every sleep. Always place the baby on their back on a firm sleep surface such as a crib or bassinet with a tight-fitting sheet.

- Avoid the use of soft bedding, including crib bumpers, blankets, pillows, and soft toys. The crib should be bare.

- Breastfeeding is recommended.

- Share a bedroom with parents, but not the same sleeping surface, preferably until the baby turns 1 but at least for the first six months. Room-sharing decreases the risk of SIDS by as much as 50 percent.

- Avoid baby’s exposure to smoke, alcohol, and illicit drugs.

As you can see, there is a recommendation to now “share a bedroom with parents,” but not the same sleeping surface. Breastfeeding is also recommended as adding protection against SIDS, but after feeding, the AAP encourages parents to move the baby to their separate sleeping space, preferably a crib or bassinet in the parents’ bedroom. Finally, the report included new evidence that supports skin-to-skin care for newborn infants.[9]

Link to Learning

The website Zero to Three has more information on infant sleep patterns and habits. Feel free to explore their multiple topics on the subject.

Try It

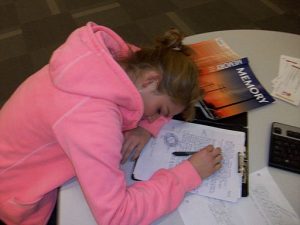

Adolescent Sleep

According to the National Sleep Foundation (NSF; 2016), to function their best, adolescents need about 8 to 10 hours of sleep each night. The most recent Sleep in America poll in 2006 indicated that adolescents between sixth and twelfth grade were not getting the recommended amount of sleep. On average, adolescents slept only 7 ½ hours per night on school nights with younger adolescents getting more than older ones (8.4 hours for sixth graders and only 6.9 hours for those in twelfth grade). For the older adolescents, only about one in ten (9%) get an optimal amount of sleep, and those who don’t are more likely to experience negative consequences the following day. These include depressed mood, feeling tired or sleepy, being cranky or irritable, falling asleep in school, and drinking caffeinated beverages (NSF, 2016). Additionally, sleep deprived adolescents are at greater risk for substance abuse, car crashes, poor academic performance, obesity, and a weakened immune system (Weintraub, 2016).

Troxel et al. (2019) found that insufficient sleep in adolescents is also a predictor of risky sexual behaviors. Reasons given for this include that those adolescents who stay out late, typically without parental supervision, are more likely to engage in a variety of risky behaviors, including risky sex, such as not using birth control or using substances before/during sex. An alternative explanation for risky sexual behavior is that the lack of sleep increases impulsivity while negatively affecting decision-making processes.

Why don’t adolescents get adequate sleep?

In addition to known environmental and social factors, including work, homework, media, technology, and socializing, the adolescent brain is also a factor. As adolescent go through puberty, their circadian rhythms change and push back their sleep time until later in the evening (Weintraub, 2016). This biological change not only keeps adolescents awake at night, it makes it difficult for them to wake up. When they are awakened too early, their brains do not function optimally. Impairments are noted in attention, academic achievement, and behavior while increases in tardiness and absenteeism are also seen.

To support adolescents’ later circadian rhythms, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that school begin no earlier than 8:30 a.m. Unfortunately, over 80% of American schools begin their day earlier than 8:30 a.m. with an average start time of 8:03 a.m. (Weintraub, 2016). Psychologists and other professionals have been advocating for later start times, based on research demonstrating better student outcomes for later start times. More middle and high schools have changed their start times to better reflect the sleep research. However, the logistics of changing start times and bus schedules are proving too difficult for some schools, leaving many adolescent vulnerable to the negative consequences of sleep deprivation. Troxel et al. (2019) cautions that adolescents should find a middle ground between sleeping too little during the school week and too much during the weekends. Keeping consistent sleep schedules of too little sleep will result in sleep deprivation but oversleeping on weekends can affect the natural biological sleep cycle making it harder to sleep on weekdays.

Link to Learning: School Start Times

As research reveals the importance of sleep for teenagers, many people advocate for later high school start times. Read about some of the research at the National Sleep Foundation on school start times or watch this TED talk by Wendy Troxel: “Why Schools Should Start Later for Teens”.

References (Click to expand)

Carpenter, R., McGarvey, C., Mitchell, E. A., Tappin, D. M., Vennemann, M. M., Smuk, M., & Carpenter, J. R. (2013). Bed sharing when parents do not smoke: is there a risk of SIDS? An individual level analysis of five major case–control studies. BMJ open, 3(5), e002299.

Colvin, J.D., Collie-Akers, V., Schunn, C., & Moon, RY (2014). Sleep environment risks for younger and older infants. Pediatrics. 134(2):e406-12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0401.

Colson, E.R., Willinger, M., Rybin, D., Heeren, T., Smith, L.A., Lister, G. & Corwin, M.J. (2013). Trends and factors associated with infant bed sharing, 1993-2010: The National Sleep Position study. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(11), 1032-1037.

Esposito, G., Setoh, P., & Bornstein, M.H. (2015). Beyond practices and values: Toward a physio-bioecological analysis of sleep arrangements in early infancy. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 264

Gordon, M. (October 2018). From Safe Sleep to Healthy Sleep: A Systemic Perspective on Sleep In the First Year. Northwest Bulletin: Family and Child Health. University of Washington. Retrieved from https://depts.washington.edu/nwbfch/infant-safe-sleep-development.

Moon, R. Y., Darnall, R. A., Feldman-Winter, L., Goodstein, M. H., Hauck, F. R., & Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. (2016). SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: evidence base for 2016 updated recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics, 138(5).

National Sleep Foundation. (2016). Teens and sleep. Retrieved from https://sleepfoundation.org/sleep topics/teens-and-sleep

Pennestri, M., Laganière, C., Bouvette-Turcot, A., Pokhvisneva, I., Steiner, M., Meaney, M. J., Gaudreau, H. on behalf of the Mavan Research Team (2018). Uninterrupted Infant Sleep, Development, and Maternal Mood. Pediatrics, Volume 142.

Richter, D., Krämer, M. D., Tang, N. K., Montgomery-Downs, H. E., & Lemola, S. (2019). Long-term effects of pregnancy and childbirth on sleep satisfaction and duration of first-time and experienced mothers and fathers. Sleep, 42(4), zsz015.

Sears, W. & Sears, M. (2001). The attachment parenting book: A commonsense guide to understanding and nurturing your baby. Boston: MA: Little Brown.

Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. (2016). SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: updated 2016 recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics, 138(5), e20162938.

Troxel, W. M., Rodriquez, A., Seelam, R., Tucker, J. Shih, R., & D’Amico. (2019). Associations of longitudinal sleep trajectories with risky sexual behavior during late adolescence. Health Psychology. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fhea0000753

Weekes-Shackelford, V. A. & Shackelford, T. K. (2005). Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human development (pp. 1238-1239). Sage Publications.

Weintraub, K. (2016). Young and sleep deprived. Monitor on Psychology, 47(2), 46-50.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

CC Licensed Content

- “Sleep and Health.” Authored by: Tera Jones for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/chapter/sleep-and-health/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology. Authored by: Laura Overstreet. Located at: http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/. License: CC BY: Attribution

Media Attributions

- Sleeping baby. Authored by: ULOVInteractive. Provided by: Needpix. Located at: https://www.needpix.com/photo/download/1048947/baby-sleeping-rest-sleeping-baby-infant-cute-little-face-child. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Baby and Dad. Authored by: Vera Kratochvil. Located at: http://www.publicdomainfiles.com/show_file.php?id=13941972617449. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Marie-Hélène Pennestri, Christine Laganière, Andrée-Anne Bouvette-Turcot, Irina Pokhvisneva, Meir Steiner, Michael J. Meaney, Hélène Gaudreau, on behalf of the Mavan Research Team (December 2018). Uninterrupted Infant Sleep, Development, and Maternal Mood. Pediatrics, Volume 142. ↵

- David Richter, Michael D Krämer, Nicole K Y Tang, Hawley E Montgomery-Downs, Sakari Lemola, Long-term effects of pregnancy and childbirth on sleep satisfaction and duration of first-time and experienced mothers and fathers, Sleep, Volume 42, Issue 4, April 2019, zsz015, https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsz015 ↵

- Macall Gordon (October 2018). From Safe Sleep to Healthy Sleep: A Systemic Perspective on Sleep In the First Year. Northwest Bulletin: Family and Child Health. University of Washington. retrieved from https://depts.washington.edu/nwbfch/infant-safe-sleep-development. ↵

- Esposito, G., Setoh, P., & Bornstein, M.H. (2015). Beyond practices and values: Toward a physio-bioecological analysis of sleep arrangements in early infancy. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 264. ↵

- Colvin, J.D., Collie-Akers, V., Schunn, C., & Moon, RY (2014). Sleep environment risks for younger and older infants. Pediatrics. 134(2):e406-12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0401. ↵

- https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/3/5/e002299.long ↵

- Sears, W. & Sears, M. (2001). The attachment parenting book: A commonsense guide to understanding and nurturing your baby. Boston: MA: Little Brown. ↵

- Colson, E.R., Willinger, M., Rybin, D., Heeren, T., Smith, L.A., Lister, G. & Corwin, M.J. (2013). Trends and factors associated with infant bed sharing, 1993-2010: The National Sleep Position study. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(11), 1032-1037. ↵

- SIDS and Other Sleep-Related Infant Deaths: Updated 2016 Recommendations for a Safe Infant Sleeping Environment. Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Pediatrics. Retrieved from https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/138/5/e20162938. ↵