22.3 End-of-Life

Learning Objectives

- List and describe the stages of loss based on Kübler-Ross’s model and describe the criticisms of the model

- Explain the philosophy and practice of palliative care

- Describe the roles of hospice and family caregivers

- Explain the different types of advanced directives

- Describe cultural differences in end of life decisions

- Explain physiological death

- Describe social and psychological death

- Describe funeral rituals in different religions

- Describe the new practice of green burials

Kübler-Ross’ Stages of Loss

Based on her work and interviews with terminally ill patients, Kübler-Ross (1975) described five stages of loss experienced by someone who faces the news of their impending untimely death. These “stages” are not really stages that a person goes through in order or only once; nor are they stages that occur with the same intensity. Indeed, the process of death is influenced by a person’s life experiences, the timing of their death in relation to life events, the predictability of their death based on health or illness, their belief system, and their assessment of the quality of their own life. Nevertheless, these stages provide a framework to help us to understand and recognize some of what a dying person experiences psychologically. And by understanding, we are more equipped to support that person as they die and to face death ourselves when our time comes (Kübler-Ross, 1975).

Denial is often the first reaction to overwhelming, unimaginable news. Denial, or disbelief or shock, protects us by allowing such news to enter slowly and to give us time to come to grips with what is taking place. The person who receives positive test results for a life-threatening condition may question the diagnosis, seek second opinions, or may simply feel a sense of psychological disbelief even though they know that the results are true.

Anger also provides us with protection in that being angry energizes us to fight against something and gives structure to a situation that may be thrusting us into the unknown. It is much easier to be angry than to be sad or in pain or depressed. It helps us to temporarily believe that we have a sense of control over our future and to feel that we have at least expressed our rage about how unfair life can be. Anger can be focused on a person, a health care provider, at God, or at the world in general. And it can be expressed over issues that have nothing to do with our death; consequently, being in this stage of loss is not always obvious.

Bargaining involves trying to think of what could be done to turn the situation around. Living better, devoting oneself to a cause, being a better friend, parent, or spouse, are all agreements one might willingly commit to if doing so would lengthen life. Asking to just live long enough to witness a family event or finish a task are examples of bargaining.

Depression is sadness and sadness is appropriate for such an event. Feeling the full weight of loss, crying, and losing interest in the outside world is an important part of the process of dying. This depression makes others feel very uncomfortable and family members may try to console their loved one. Sometimes hospice care may include the use of antidepressants to reduce depression during this stage.

Acceptance involves learning how to carry on and to incorporate this aspect of the life span into daily existence. Reaching acceptance does not in any way imply that people who are dying are happy about it or content with it. It means that they are facing it and continuing to make arrangements and to say what they wish to say to others. Some terminally ill people find that they live life more fully than ever before after they come to this stage.

In some ways, these five stages serve as coping mechanisms, allowing the individual to make sense of the situation while coming to terms with what is happening. They are, in other words, the mind’s way of gradually recognizing the implications of one’s impending death and giving them the chance to process it. These stages provide a type of framework in which dying is experienced, although it is not exactly the same for every individual in every case. When death comes at the an advanced age, people have had more opportunity to come to grips with impending death and so may show only acceptance. In fact, research shows that as people age, they become less and less afraid of death, so that for many who are old-old (i.e., 85+ years), death seems like a natural next step.

Since Kübler-Ross presented these stages of loss, several other models have been developed. These subsequent models, in many ways, build on that of Kübler-Ross, offering expanded views of how individuals process loss and grief. While Kübler-Ross’ model was restricted to dying individuals, subsequent theories tended to focus on loss as a more general construct. This ultimately suggests that facing one’s own death is just one example of the grief and loss that human beings can experience, and that other loss or grief-related situations tend to be processed in a similar way.

End-of-Life Decisions

Curative, Palliative, and Hospice Care

When individuals become ill, they need to make choices about the treatment they wish to receive. One’s age, type of illness, and personal beliefs about dying affect the type of treatment chosen (Bell, 2010).

Curative care is designed to overcome and cure disease and illness (Fox, 1997). Its aim is to promote complete recovery, not just to reduce symptoms or pain. An example of curative care would be chemotherapy. While curing illness and disease is an important goal of medicine, it is not its only goal. As a result, some have criticized the curative model as ignoring the other goals of medicine, including preventing illness, restoring functional capacity, relieving suffering, and caring for those who cannot be cured.

Palliative care focuses on providing comfort and relief from physical and emotional pain to patients throughout their illness, even while being treated (NIH, 2007). In the past, palliative care was confined to offering comfort for the dying. Now it is offered whenever patients suffer from chronic illnesses, such as cancer or heart disease (IOM, 2015). Palliative care is also part of hospice programs.

Hospice emerged in the United Kingdom in the mid-20th century as a result of the work of Cicely Saunders. This approach became popularized in the U.S. by the work of Elizabeth Kübler-Ross (IOM, 2015), and by 2012 there were 5,500 hospice programs in the U.S. (National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO), 2013).

Hospice care whether at home, in a hospital, nursing home, or hospice facility involves a team of professionals and volunteers who provide terminally ill patients with medical, psychological, and spiritual support, along with support for their families (Shannon, 2006). The aim of hospice is to help the dying be as free from pain as possible, and to comfort both the patients and their families during a difficult time.

In order to enter hospice, a patient must be diagnosed as terminally ill with an anticipated death within 6 months (IOM, 2015). The patient is allowed to go through the dying process without invasive treatments. Hospice workers try to inform the family of what to expect and reassure them that much of what they see is a normal part of the dying process.

According to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (2019) there are four types of hospice care in America:

- Routine hospice care, where the patient has chosen to receive hospice care at home, is the most common form of hospice.

- Continuous home care is predominantly nursing care, with caregiver and hospice aides supplementing this care, to manage pain and acute symptom crises for 8 to 24 hours in the home.

- Inpatient respite care is provided by a hospital, hospice, or long-term care facility to provide temporary relief for family caregivers.

- General inpatient care is provided by a hospital, hospice, or long-term care facility when pain and acute symptom management can on be handled in other settings.

In 2017, an estimated 1.5 million people residing in America received hospice care (NHPCO, 2019). The majority of patients on hospice were patients suffering from dementia, heart disease, or cancer, and typically did not enter hospice until the last few weeks prior to death. Almost one out of three patients were on hospice for less than a week.

According to Shannon (2006), the basic elements of hospice include:

- Care of the patient and family as a single unit

- Pain and symptom management for the patient

- Having access to day and night care

- Coordination of all medical services

- Social work, counseling, and pastoral services

- Bereavement counseling for the family up to one year after the patient’s death

Although hospice care has become more widespread, these new programs are subject to more rigorous insurance guidelines that dictate the types and amounts of medications used, length of stay, and types of patients who are eligible to receive hospice care (Weitz, 2007). Thus, more patients are being served, but providers have less control over the services they provide, and lengths of stay are more limited. In addition, a recent report by the Office of the Inspector General at U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2018) highlighted some of the vulnerabilities of the hospice system in the U.S. Among the concerns raised were that hospices did not always provide the care that was needed and sometimes the quality of that care was poor, even at Medicare certified facilities.

Not all racial and ethnic groups feel the same way about hospice care. African-American families may believe that medical treatment should be pursued on behalf of an ill relative as long as possible and that only God can decide when a person dies. Chinese-American families may feel very uncomfortable discussing issues of death or being near the deceased family member's body. The view that hospice care should always be used is not held by everyone, and health care providers need to be sensitive to the wishes and beliefs of those they serve (Coolen, 2012).

Watch It

Watch this video to better understand the setting, circumstances, and services associated with hospice care.

You can view the transcript for “Understanding Hospice Care” here (opens in new window).

Family Caregivers

According to the Institute of Medicine (2015), it is estimated that 66 million Americans, or 29% of the adult population, are caregivers for someone who is dying or chronically ill. Two-thirds of these caregivers are women. This care takes its toll physically, emotionally, and financially. Family caregivers may face the physical challenges of lifting, dressing, feeding, bathing, and transporting a dying or ill family member. They may worry about whether they are performing all tasks safely and properly, as they receive little training or guidance. Such caregiving tasks may also interfere with their ability to take care of themselves and meet other family and workplace obligations. Financially, families may face high out of pocket expenses (IOM, 2015).

As can be seen in Table 22.1, most family caregivers are providing care by themselves with little professional intervention, are employed, and have provided care for more than 3 years. The annual loss of productivity in the U.S. was $25 billion in 2013 as a result of work absenteeism due to providing this care. As the prevalence of chronic disease rises, the need for family caregivers is growing. Unfortunately, the number of potential family caregivers is declining as the large baby boomer generation enters into late adulthood (Redfoot, Feinberg, & Houser, 2013).

Table 22.1 Characteristics of Family Caregivers in the United States

| Characteristic | Percentage |

|---|---|

| No home visits by health care professionals | 69% |

| Caregivers are also employed | 72% |

| Duration of employed workers who have been caregiving for 3+ years | 55% |

| Caregivers for the elderly | 67% |

adapted from Lally & Valentine-French, 2019 and IOM, 2015

Advanced Directives

Advanced care planning refers to all documents that pertain to end-of-life care. These include advance directives and medical orders. Advance directives include documents that mention a health care agent and living wills. These are initiated by the patient. Living wills are written or video statements that outline the health care initiates the person wishes under certain circumstances. Durable power of attorney for health care names the person who should make health care decisions in the event that the patient is incapacitated. In contrast, medical orders are crafted by a medical professional on behalf of a seriously ill patient. Unlike advanced directives, as these are doctor’s orders, they must be followed by other medical personnel. Medical orders include Physician Orders for Life-sustaining Treatment (POLST), do-not-resuscitate, do-not-incubate, or do-not-hospitalize. In some instances, medical orders may be limited to the facility in which they were written. Several states have endorsed POLST so that they are applicable across heath care settings (IOM, 2015).

Despite the fact that many Americans worry about the financial burden of end-of-life care, “more than one-quarter of all adults, including those aged 75 and older, have given little or no thought to their end-of-life wishes, and even fewer have captured those wishes in writing or through conversation” (IOM, 2015, p. 18).

Link to Learning: Organ Donation

Although not explicitly an advance directive, an individual can choose to register as an organ donor. This designation signals to medical personnel and the individuals' family their wish that they donate their organs if possible after their death. You can learn more about organ donation from UNOS, United Network for Organ Sharing, a national nonprofit organization that manages organ donation in the United States under a contract with the federal government. Many people register to become organ donors when they obtain or renew their driver's licenses, but if you are interested in becoming an organ donor you can register at this link.

Cultural Differences in End-of-Life Decisions

Cultural factors strongly influence how doctors, other health care providers, and family members communicate bad news to patients, the expectations regarding who makes the health care decisions, and attitudes about end-of-life care (Ganz, 2019; Searight & Gafford, 2005a). In Western medicine, doctors take the approach that patients should be told the truth about their health. Blank (2011) reports that 75% of the world’s population do not conduct medicine by the same standards. Thus, outside Western nations, and even among certain racial and ethnic groups within the those nations, doctors and family members may conceal the full nature of a terminal illness, as revealing such information is viewed as potentially harmful to the patient, or at the very least is seen as disrespectful and impolite. Chattopadhyay and Simon (2008) reported that in India doctors routinely abide by the family’s wishes and withhold information from the patient, while in Germany doctors are legally required to inform the patient. In addition, many doctors in Japan and in numerous African nations used terms such as “mass,” “growth,” and “unclean tissue” rather than referring to cancer when discussing the illness to patients and their families (Holland et al., 1987). Family members also actively protect terminally ill patients from knowing about their illness in many Hispanic, Chinese, and Pakistani cultures (Kaufert & Putsch, 1997; Herndon & Joyce, 2004).

In western medicine, we view the patient as autonomous in health care decisions (Chattopadhyay & Simon, 2008; Searight & Gafford, 2005a). However, in other nations the family or community plays the main role, or decisions are made primarily by medical professionals, or the doctors in concert with the family make the decisions for the patient. For instance, in comparison to European Americans and African Americans, Koreans and Mexican-Americans are more likely to view family members as the decision makers rather than just the patient (Berger, 1998; Searight & Gafford, 2005a). In many Asian cultures, illness is viewed as a “family event”, not just something that impacts the individual patient (Blank, 2011; Candib, 2002; Chattopadhyay & Simon, 2008). Thus, there is an expectation that the family has a say in the health care decisions. As many cultures attribute high regard and respect for doctors, patients and families may defer some of the end-of-life decision making to the medical professionals (Searight & Gafford, 2005b).

The notion of advanced directives, which spell out a patient's wishes for end-of-life-care, hold little or no relevance in many cultures outside of western society (Blank, 2011). For instance, in India advanced directives are virtually non-existent, while in Germany they are regarded as a major part of health care (Chattopadhyay & Simon, 2008). Moreover, end-of-life decisions involve how much medical aid should be used. In the United States, Canada, and most European countries artificial feeding is more commonly used once a patient has stopped eating, while in many other nations lack of eating is seen as a sign, rather than a cause, of dying and do not consider using a feeding tube (Blank, 2011).

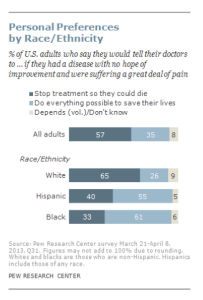

According to a Pew Research Center Survey (Lipka, 2014), while death may not be a comfortable topic to ponder, 37% of their survey respondents had given a great deal of thought about their end-of-life wishes, with 35% having put these in writing. Yet, over 25% had given no thought to this issue. Lipka (2014) also found that there were clear racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life wishes (see Figure 22.11). Whites are more likely than Blacks and Hispanics to prefer to have treatment stopped if they have a terminal illness. In contrast, the majority of Blacks (61%) and Hispanics (55%) prefer that everything be done to keep them alive. Searight and Gafford (2005a) suggest that the low rate of completion of advanced directives among non-whites may reflect a distrust of the U.S. health care system as a result of the health care disparities non-whites have experienced. Among Hispanics, patients may also be reluctant to select a single family member to be responsible for end-of-life decisions out of a concern of isolating the person named and of offending other family members, as this is commonly seen as a “family responsibility” (Morrison et al., 1998).

Process of Dying

One way to understand death and dying is to look more closely at physiological death, social death, and psychological death. These deaths do not occur simultaneously, nor do they always occur in a set order. Rather, a person's physiological, social, and psychological deaths can occur at different times (Butow, 2017).

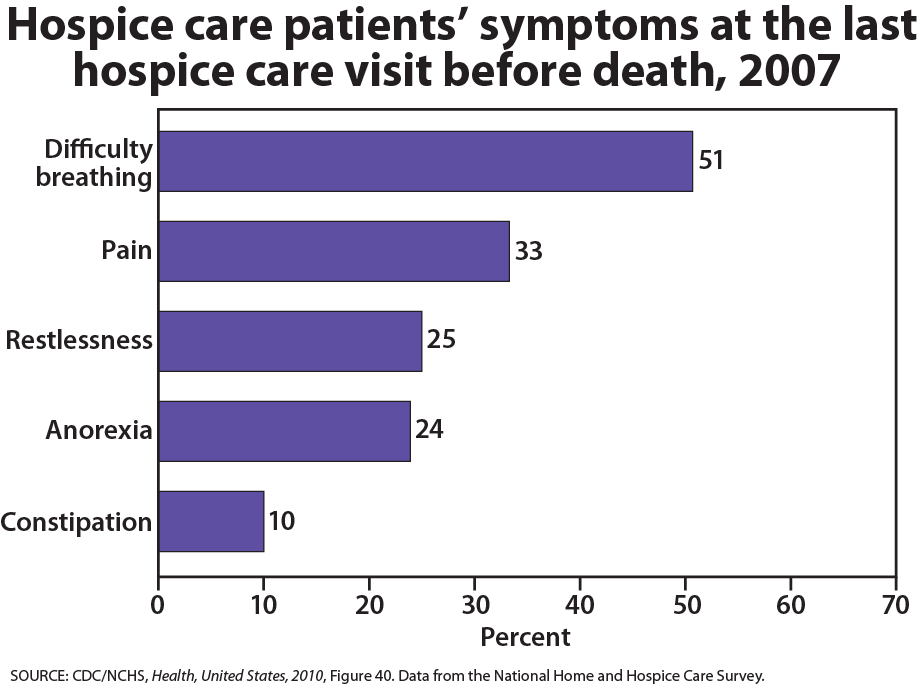

Physiological death occurs when the vital organs no longer function. The digestive and respiratory systems begin to shut down during the gradual process of dying. A dying person no longer wants to eat as digestion slows, the digestive track loses moisture, and chewing, swallowing, and elimination become painful processes. Circulation slows and mottling, or the pooling of blood, may be noticeable on the underside of the body, appearing much like bruising. Breathing becomes more sporadic and shallow and may make a rattling sound as air travels through mucus- filled passageways. Agonal breathing refers to gasping, labored breaths caused by an abnormal pattern of brainstem reflex. The person often sleeps more and more and may talk less, although they may continue to hear. The kinds of symptoms noted prior to death in patients under hospice care (care focused on helping patients die as comfortably as possible) are noted below.

Watch It

Death we see depicted on TV and in the movies is often inaccurate, and many of us have never witnessed a person going through the dying process. The following video provides an example of what actively dying looks like in a hospice setting. A hospice nurse provides commentary (including content warnings) on what the dying process looks like.

When a person is brain dead, or no longer has brain activity, they are clinically dead. Physiological death may take 72 or fewer hours. This is different than a vegetative state, which occurs when the cerebral cortex no longer registers electrical activity but the brain stems continues to be active. Individuals who are kept alive through life support may be classified this way.

Social death begins much earlier than physiological death. Social death occurs when others begin to withdraw from someone who is terminally ill or has been diagnosed with a terminal illness. Those diagnosed with conditions such as AIDS or cancer may find that friends, family members, and even health care professionals begin to say less and visit less frequently. Meaningful discussions may be replaced with comments about the weather or other topics of light conversation. Doctors may spend less time with patients after their prognosis becomes poor. Why do others begin to withdraw? Friends and family members may feel that they do not know what to say or that they can offer no solutions to relieve suffering. They withdraw to protect themselves against feeling inadequate or from having to face the reality of death. Health professionals, trained to heal, may also feel inadequate and uncomfortable facing decline and death. A patient who is dying may be referred to as "circling the drain," meaning that they are approaching death. People in nursing homes may live as socially dead for years with no one visiting or calling. Social support is important for quality of life and those who experience social death are deprived from the benefits that come from loving interaction with others.

Psychological death occurs when the dying person begins to accept death and to withdraw from others and regress into the self. This can take place long before physiological death (or even social death if others are still supporting and visiting the dying person) and can even bring physiological death closer. People have some control over the timing of their death and can hold on until after important occasions or die quickly after having lost someone important to them. In some cases, individuals can give up their will to live. This is often at least partially attributable to a lost sense of identity (Butow, 2017). The individual feels consumed by the reality of making final decisions, planning for loved ones—especially children, and coping with the process of their own physical death.

Interventions based on the idea of self-empowerment enable patients and families to identify and ultimately achieve their own goals of care, thus producing a sense of empowerment. Self-empowerment for terminally ill individuals has been associated with a perceived ability to manage and control things such as medical actions, changing life roles, and psychological impacts of the illness (Butow, 2017).

Treatment plans that are able to incorporate a sense of control and autonomy into the dying individual's daily life have been found to be particularly effective in regards to general attitude as well as depression level. For example, it has been found that when dying individuals are encouraged to recall situations from their lives in which they were active decision makers, explored various options, and took action, they tend to have better mental health than those who focus on themselves as victims. Similarly, there are several theories of coping that suggest active coping (seeking information, working to solve problems) produces more positive outcomes than passive coping (characterized by avoidance and distraction). Although each situation is unique and depends at least partially on the individual's developmental stage, the general consensus is that it is important for caregivers to foster a supportive environment and partnership with the dying individual, which promotes a sense of independence, control, and self-respect.

Try It

Religious Practices after Death

Funeral rites are expressions of loss that reflect personal and cultural beliefs about the meaning of death and the afterlife. Ceremonies provide survivors a sense of closure after a loss. These rites and ceremonies send the message that the death is real and allow friends and loved ones to express their love and respect for those who die. Under circumstances in which a person has been lost and presumed dead or when family members were unable to attend a funeral, there can continue to be a lack of closure that makes it difficult to grieve and to learn to live with loss. Although many people are still in shock when they attend funerals, the ceremony still provides a marker of the beginning of a new period of one's life as a survivor. The following are some of the religious practices regarding death, however, individual religious interpretations and practices may occur (Dresser & Wasserman, 2010; Schechter, 2009).

Hinduism. The Hindu belief in reincarnation accelerates the funeral ritual, and deceased Hindus are cremated as soon as possible. After being washed, the body is anointed, dressed, and then placed on a stand decorated with flowers ready for cremation. Once the body has been cremated, the ashes are collected and, if possible, dispersed in one of India’s holy rivers.

Judaism. Among the Orthodox, the deceased is first washed and then wrapped in a simple white shroud. Males are also wrapped in their prayer shawls. Once shrouded the body is placed into a plain wooden coffin. The burial must occur as soon as possible after death, and a simple service consisting of prayers and a eulogy is given. After burial the family members typically gather in one home, often that of the deceased, and receive visitors. This is referred to as “sitting shiva”.

Muslim. In Islam the deceased are buried as soon as possible, and it is a requirement that the community be involved in the ritual. The individual is first washed and then wrapped in a plain white shroud called a kafan. Next, funeral prayers are said followed by the burial. The shrouded dead are placed directly in the earth without a casket and deep enough not to be disturbed. They are also positioned in the earth, on their right side, facing Mecca, Saudi Arabia.

Roman Catholic. Before death an ill Catholic individual is anointed by a priest, commonly referred to as the Anointing of the Sick. The priest recites a prayer and applies consecrated oil to the forehead and hands of the ill person. The individual also takes a final communion consisting of consecrated bread and wine. The funeral rites consist of three parts. First is the wake that usually occurs in a funeral parlor. The body is present, and prayers and eulogies are offered by family and friends. The funeral mass is next which includes an opening prayer, bible readings, liturgy, communion, and a concluding rite. The funeral then moves to the cemetery where a blessing of the grave, scripture reading, and prayers conclude the funeral ritual.

Diversity of Beliefs and Traditions Across Religions and Cultures

Table 22.1 Religious Beliefs about Death, Dying, and Funerals

| Religion | Beliefs pertaining to death | Preparation of the Body | Funeral |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catholic | Beliefs include that the deceased travels from this world into eternal afterlife where the soul can reside in heaven, hell, or purgatory. Sacraments are given to the dying. | Organ donation and autopsy are permitted. | Cremation historically forbidden until 1963.The Vigil occurs the evening before the funeral mass is held. Mass includes Eucharist. If a priest is not available, a deacon can lead funeral services. Rite of committal takes place with interment. |

| Protestant | Belief in Jesus Christ and the Bible is central, although differences in interpretation exist in the various denominations. Beliefs include an afterlife. | Organ donation and autopsy are permitted. | Cremation or burial is accepted. Funeral can be held in funeral home or in church and led by minister or chaplain. |

| Jewish | Tradition cherishes life but death itself is not viewed as a tragedy. Views on an afterlife vary with the denomination (Reform, Conservative, or Orthodox). | Autopsy and embalming are forbidden under ordinary circumstances. Open caskets are not permitted. | Funeral held as soon as possible after death. Dark clothing is worn at and after the funeral/burial. It is forbidden to bury the decedent on the Sabbath or festivals. Three mourning periods are held after the burial, with Shiva being the first seven days after burial. |

| Buddhist | Both a religion and way of life with the goal of enlightenment. Beliefs include that life is a cycle of death and rebirth. | Goal is a peaceful death. Statue of Buddha may be placed at bedside as the person is dying. Organ donation is not permitted. Incense is lit in the room following death. | Family washes and prepares the body. Cremation is preferred but if buried, deceased should be dressed in regular daily clothes instead of fancy clothing. Monks may be present at the funeral and lead the chanting. |

| Native American | Beliefs vary among tribes. Sickness is thought to mean that one is out of balance with nature. Thought that ancestors can guide the deceased. Believe that death is a journey to another world. Family may or may not be present for death. | Preparation of the body may be done by family. Organ donation generally not preferred. | Most burials are natural or green. Various practices differ with tribe. Among the Navajo, hearing an owl or coyote is a sign of impending death and the casket is left slightly open so the spirit can escape. Navajo and Apache tribes believe that spirits of deceased can haunt the living. The Comanche tribe buries the dead in the place of death or in a cave. |

| Hindu | Beliefs include reincarnation, where a deceased person returns in the form of another, and Karma. | Organ donation and autopsy are acceptable. Bathing the body daily is necessary. Death and dying must be peaceful. Customary for body to not be left alone until cremated. | Prefer cremation within 24 hours after death. Ashes should be scattered in sacred rivers. |

| Muslim | Muslims believe in an afterlife and that the body must be quickly buried so that the soul may be freed. | Embalming and cremation are not permitted. Autopsy is permitted for legal or medical reasons only. After death, the body should face Mecca or the East. Body is prepared by a person of the same gender. | Burial takes place as soon as possible. Women and men will sit separately at the funeral. Flowers and excessive mourning are discouraged. Body is usually buried in a shroud and is buried with the head pointing toward Mecca. |

(ELNEC, 2010; Health Care Chaplaincy, 2009).

Common Funeral Traditions in the United States

Options for Final Arrangement: Burial or Cremation

One of the reasons that people should discuss their wishes before they become ill is so their family will know what final arrangements they would like to have after they die. Although some believe it is morbid to talk about end of life and funeral wishes while one is young and healthy, it can be a very important conversation to have. The family has had to make many difficult decisions while their loved one was dying, and then, after death, they have to plan the funeral. This is one of the most difficult things that people have to do in their lives. Although most people who die are older, there can be death that occurs in people of all ages, including newborn babies, infants, children, adolescents, and young adults.

One of the greatest decisions the family will have to make (unless specified in advance by the individual) is whether their loved one will be buried or cremated. Both methods have been around for thousands of years, and it is really a matter of personal preference (and sometimes family history). When burial is elected, the deceased will be interred in the ground in a cemetery, entombed in a vault in a mausoleum, or, more recently, have a “green burial” (see next section below). Burials can be expensive; the average median cost of a funeral is over $8,000. (National Funeral Directors Association, 2012). The deceased will need to have their body prepared and/or embalmed. Embalming is the process in which the blood is removed from the body via the veins and replaced with an embalming solution via the arteries, usually containing formaldehyde and other chemicals (National Funeral Directors Association, 2012). The body will be prepared cosmetically and dressed before being placed in the casket. Along with the casket, there is usually a vault that is placed into the ground that encompasses the casket. There are also fees associated with the grave or mausoleum space and opening up the ground/vault for internment. The funeral director has a fee for their services and use of the funeral home for visitation. A hearse is the vehicle that transports the deceased from the funeral home to the church (if applicable) and to the cemetery. The family will obtain a death certificate and may write an obituary for the local newspaper. Lastly, if burial is used, often there will be a headstone or marker purchased for the grave.

Although both burial and cremation can be costly, cremation is usually less expensive than a burial. Cremation is the process by which the deceased body is burned into ashes using heat and fire. Any fragments that remain after the procedure, including bones, are ground down to a finer consistency with special tools at the crematorium. When selecting this method, the body does not get embalmed. The body is placed into an approved container, such as a wooden casket, for the cremation. Certified crematoriums have special policies and procedures in place to ensure that the highest quality care and dignity are provided during the cremation process. The remains are placed into a special container called an urn. There are many choices available to families for urn styles as well as caskets. There can still be formal visitation and funeral practices that take place before the deceased is cremated, or a memorial service can be held with the ashes of the deceased after cremation occurs. Cremated remains are then either buried in the ground or mausoleum in a cemetery, kept by the family, scattered in an outdoor location or divided up between family members (although this practice is not used in some religions who believe that the remains of a person should not be divided).

Green Burial

In 2017, the median cost of an adult funeral with viewing and burial was $8,775. The median cost for viewing and cremation was $6,260 (National Funeral Directors Association (NFDA), 2019). The same NFDA survey found that nearly half of all respondents had attended a funeral in a non-traditional setting, such as an outdoor setting that was meaningful to the deceased, and over half of the respondents said they would be interested in exploring green funeral options (NFDA, 2017).

According to the Green Burial Council (GBC) (2019) Americans bury over 64 thousand tons of steel, 17 thousand tons of copper and bronze, 1.6 million tons of concrete, 20 million feet of wood, and over 4 million gallons of embalming fluid every year. As a result, there has been a growing interest in green or natural burials. Green burials attempt to reduce the impact on the environment at every stage of the funeral. This can include using recycled paper, biodegradable caskets, cotton shroud in the place of any casket, formaldehyde free, or no embalming, and trying to maintain the natural environment around the burial site (GBC, 2019). According to the NFDA (2017), many cemeteries have reported that consumers are requesting green burial options, and since many of the add-ons of a traditional burial, such as a concrete vault, embalming, and casket are not required, the cost can be substantially less.

Visiting Hours

Visiting hours, also called visitation or a wake, is when the deceased person’s body is prepared and placed on display in a casket. Formal visiting hours are held at the funeral home in which family and friends of the deceased can come and say their final good-byes and offer condolences to the family. Visiting hours usually occur 1-2 days before the funeral or memorial service. Many times there is a formal book that visitors can sign. Flowers and other memorial displays often are part of this time. Many families will display photos or prized possessions of their loved one or have favorite music played in the background. More recently, families are using technology to make video displays of pictures or home videos of their loved one during visitation.

The casket can be open or closed during visiting hours. An open casket is where the deceased body is visible to family and guests; a closed casket means that the deceased body cannot be seen by family or guests. Often if the death resulted from severe trauma, a closed casket is the preferred method. In certain religions, such as Judaism (mentioned previously), deceased are never displayed in an open casket, nor is embalming allowed.

The Funeral or Memorial Service

A funeral is the formal ritual that takes place which is often officiated by clergy from the decedent’s religion. This can take place at the funeral home or in a church. The Catholic faith usually has a funeral mass that takes place at a church officiated by the priest. The casket is often closed at church funerals. Sometimes, family or friends of the deceased will speak or give a eulogy about their loved one during the funeral or memorial service. Internment follows the funeral service and a procession of guests usually follow the hearse carrying the casket or remains of the deceased to the cemetery.

The Burial or Internment

The burial or internment of the deceased can take place right after the funeral or memorial service or at some later date. The clergy will often accompany the deceased and family to the cemetery and provide a small service at the grave. Many times the grave or mausoleum will be blessed as the deceased is interred. If the deceased was a member of the military, a special military service may be conducted at that time. The casket is usually wrapped in the American flag and then given to the decedent’s next of kin. In the U.S., gatherings are commonly held following a funeral service in which family and friends gather for a meal.

References (Click to expand)

Bell, K. W. (2010). Living at the end of life. New York: Sterling Ethos.

Berger, J. T. (1998). Cultural discrimination in mechanisms for health decisions: A view from New York. Journal of Clinical Ethics, 9, 127-131.

Blank, R.H. (2011). End of life decision making across cultures. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 39(2), 201–214

Butow, P. (2017). Psychology and end of life. Australian Psychologist, 52(5), 331-334.

Candib, L. M. (2002). Truth telling and advanced planning at end of life: problems with autonomy in a multicultural world. Family System Health, 20, 213-228.

Chattopadhyay, S., & Simon, A. (2008). East meets west: Cross-cultural perspective in end-of-life decision making from Indian and German viewpoints. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 11, 165-174.

Coolen, P. R. (2012). Cultural relevance in end-of-life care. EthnoMed, University of Washington. Retrieved from https://ethnomed.org/clinical/end-of-life/cultural-relevance-in-end-of-life-care

Dresser, N. & Wasserman, F. (2010). Saying goodbye to someone you love. New York: Demos Medical Publishing.

End of Life Nursing Education Consortium (2010). ELNEC – core curriculum training program. City of Hope and American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/ELNEC

Fox, E. (1997). Predominance of the curative model of medical care: A residual problem. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278(9), 761-764. Retrieved from: http://www.fammed.washington.edu/palliativecare/requirements/FOV1- 00015079/PCvCC.htm#11

Funeral Directors Association. (2017). NFDA consumer survey: Funeral planning not a priority for Americans. Retrieved from http://www.nfda.org/news/media-center/nfda-news-releases/id/2419.

Ganz, F. D. (2019). Improving Family Intensive Care Unit Experiences at the End of Life: Barriers and Facilitators. Critical Care Nurse, 39(3), 52–58.

Green Burial Council. (2019). Green burial defined. Retrieved from https://www.greenburialcouncil.org/green_burial_defined.html

Herndon, E., & Joyce, L. (2004). Getting the most from language interpreters. Family Practice Management, 11, 37-40.

Holland, J. L., Geary, N., Marchini, A., & Tross, S. (1987). An international survey of physician attitudes and practices in regard to revealing the diagnosis of cancer. Cancer Investigation, 5, 151-154.

Institute of Medicine. (2015). Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kaufert, J. M., & Putsch, R. W., (1997). Communication through interpreters in healthcare: Ethical dilemmas arising from differences in class, culture, language, and power. Journal of Clinical Ethics, 8, 71-87.

Kübler-Ross, E. (1975). Death: The final stage of growth. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Lipka, M. (2014). 5 facts about Americans’ views on life and death issues. Pew Research Institute. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/01/07/5-facts-about-americans-views-on-life-and-death-issues/

Morrison, R. S., Zayas, L. H., Mulvihill, M., Baskin, S. A., & Meier, D. E. (1998). Barriers to completion of healthcare proxy forms: A qualitative analysis of ethnic differences. Journal of Clinical Ethics, 9, 118-126.

National Funeral Directors Association. (2019). Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.nfda.org/news/statistics.

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2013). NHPCO’s facts and figures: Hospice care in America 2013 edition. Retrieved from http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2013_Facts_Figures.pdf

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2019). NHPCO facts and figures: 2018 edition. Retrieved from https://39k5cm1a9u1968hg74aj3x51-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wpcontent/uploads/2019/07/2018_NHPCO_Facts_Figures.pdf

National Institute on Health. (2007). Hospitals Embrace the Hospice Model. Retrieved from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/news/fullstory_43523.html

Redfoot, D., Feinberg, L., & Houser, A. (2013). The aging of the baby boom and the growing care gap: A look at future declines in the availability of family caregivers. AARP. Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/ltc/2013/baby-boom-and-the-growing-care-gapinsight-AARP-ppi-ltc.pdf

Schechter, H. (2009). The whole death catalog. New York: Ballantine Books.

Searight, H. R., & Gafford, J. (2005a). Cultural diversity at end of life: Issues and guidelines for family physicians. American Family Physician, 71(3), 515-522.

Searight, H. R., & Gafford, J. (2005b). “It’s like playing with your destiny”: Bosnian immigrants’ views of advance directives and end-of-life decision-making. Journal or Immigrant Health, 7(3), 195-203.

Shannon, J. B. (2006). Death and dying sourcebook. Detroit, MI: Omnigraphics.

Weitz, R. (2007). The sociology of health, illness, and health care: A critical approach (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

CC Licensed Content

- “Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0

- Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- “Grief in Children and Developmental Concepts of Death” by Adam Himebauch, Robert Arnold MD, and Carol May is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-4.0

- Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology. Authored by: Laura Overstreet. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- The Process of Dying. Authored by: Sarah Carter, Ph.D., for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- "Diversity in Dying: Death Across Cultures" in SUNY ER Services Nursing Care at the End of Life from LumenLearning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- "Palliative Care." by Sarah Carter, Ph.D., for Lumen Learning is licensed under a CC BY: Attribution.

All Rights Reserved Content

- "This is what actively dying looks like hospice care" is embedded according to YouTube terms of service.

- "Understanding Hospice Care" is embedded according to YouTube terms of service.

Media Attributions

- hospice-1793998_640 © truthseeker08

- family-caregivers-older-patients-inline is licensed under a Public Domain license

- endoflifepref © Pew Research Center is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Symptoms before death is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- greenburial © Peter Holmes is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license