13.1 Foundations of Language

Learning Objectives

- Describe components of language.

- Identify and compare the theories of language.

Components of Language

Phonemes

A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound that makes a meaningful difference in a language. The word “bit” has three phonemes. In spoken languages, phonemes are produced by the positions and movements of the vocal tract, including our lips, teeth, tongue, vocal cords, and throat, whereas in sign languages phonemes are defined by the shapes and movement of the hands.

There are hundreds of unique phonemes that can be made by human speakers, but most languages only use a small subset of the possibilities. English contains about 45 phonemes, whereas other languages have as few as 15 and others more than 60. The Hawaiian language contains fewer phonemes as it includes only 5 vowels (a, e, i, o, and u) and 7 consonants (h, k, l, m, n, p, and w).

Infants are born able to detect all phonemes, but they lose their ability to do so as they get older; by 10 months of age a child’s ability to recognize phonemes becomes very similar to that of the adult speakers of the native language. Phonemes that were initially differentiated come to be treated as equivalent (Werker & Tees, 2002).

Morphemes

Whereas phonemes are the smallest units of sound in language, a morpheme is a string of one or more phonemes that makes up the smallest units of meaning in a language. Some morphemes are prefixes and suffixes used to modify other words. For example, the syllable “re-” as in “rewrite” or “repay” means “to do again,” and the suffix “-est” as in “happiest” or “coolest” means “to the maximum.”

Semantics

Semantics refers to the set of rules we use to obtain meaning from morphemes. For example, adding “ed” to the end of a verb makes it past tense.

Syntax

Syntax is the set of rules of a language by which we construct sentences. Each language has a different syntax. The syntax of the English language requires that each sentence have a noun and a verb, each of which may be modified by adjectives and adverbs. Some syntaxes make use of the order in which words appear. For example, in English the meaning of the sentence “The man bites the dog” is different from “The dog bites the man.”

Pragmatics

The social side of language is expressed through pragmatics, or how we communicate effectively and appropriately with others. Examples of pragmatics include turn-taking, staying on topic, volume and tone of voice, and appropriate eye contact.

Lastly, words do not possess fixed meanings, but change their interpretation as a function of the context in which they are spoken. We use contextual information, the information surrounding language, to help us interpret it. Examples of contextual information include our knowledge and nonverbal expressions, such as facial expressions, postures, and gestures. Misunderstandings can easily arise if people are not attentive to contextual information or if some of it is missing, such as it may be in newspaper headlines or in text messages.

Theories of Language Development

Psychological theories of language learning differ in terms of the importance they place on nature and nurture. Remember that we are a product of both nature and nurture. Researchers now believe that language acquisition is partially inborn and partially learned through our interactions with our linguistic environment (Gleitman & Newport, 1995; Stork & Widdowson, 1974). First to be discussed are the biological theories, including nativist, brain areas and critical periods. Next, learning theory and social pragmatics will be presented.

Nativism

The linguist Noam Chomsky advocates for the nature approach to language, arguing that human brains contain a language acquisition device (LAD) that includes a universal grammar that underlies all human language (Chomsky, 1965, 1972). According to this approach, each of the many languages spoken around the world (there are between 6,000 and 8,000) is an individual example of the same underlying set of procedures that are hardwired into human brains. Chomsky’s account proposes that children are born with a knowledge of general rules of syntax that determine how sentences are constructed. Language develops as long as the infant is exposed to it. No teaching, training, or reinforcement is required for language to develop as proposed by Skinner.

Chomsky differentiates between the deep structure of an idea; that is, how the idea is represented in the fundamental universal grammar that is common to all languages, and the surface structure of the idea or how it is expressed in any one language. Once we hear or express a thought in surface structure, we generally forget exactly how it happened. At the end of a lecture, you will remember a lot of the deep structure (i.e., the ideas expressed by the instructor), but you cannot reproduce the surface structure (the exact words that the instructor used to communicate the ideas).

Although there is general agreement among psychologists that babies are genetically programmed to learn language, there is still debate about Chomsky’s idea that there is a universal grammar that can account for all language learning. Evans and Levinson (2009) surveyed the world’s languages and found that none of the presumed underlying features of the language acquisition device were entirely universal. In their search they found languages that did not have noun or verb phrases, that did not have tenses (e.g., past, present, future), and even some that did not have nouns or verbs at all, even though a basic assumption of a universal grammar is that all languages should share these features.

Brain areas for language

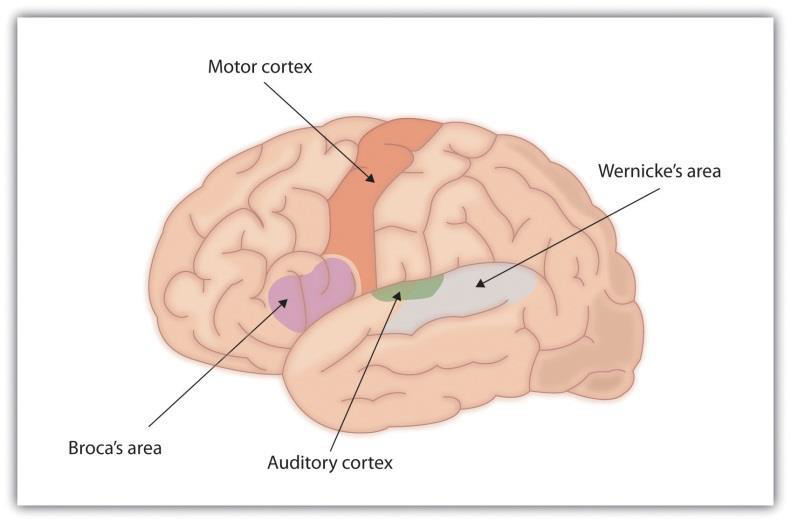

For the 90% of people who are right-handed, language is stored and controlled by the left cerebral cortex, although for some left-handers this pattern is reversed. These differences can easily be seen in the results of neuroimaging studies that show that listening to and producing language creates greater activity in the left hemisphere than in the right. Broca’s area, an area in front of the left hemisphere near the motor cortex, is responsible for language production (Figure 13.3). This area was first localized in the 1860s by the French physician Paul Broca, who studied patients with lesions to various parts of the brain. Wernicke’s area, an area of the brain next to the auditory cortex, is responsible for language comprehension.

For most people the left hemisphere is specialized for language. Broca’s area, near the motor cortex, is involved in language production, whereas Wernicke’s area, near the auditory cortex, is specialized for language comprehension.

Is there a critical period for learning language?

Psychologists believe there is a critical period, a time in which learning can easily occur, for language. This critical period appears to be between infancy and puberty (Lenneberg, 1967; Penfield & Roberts, 1959), but isolating the exact timeline has been elusive. Children who are not exposed to language early in their lives will likely never grasp the grammatical and communication nuances of language. Case studies, including Victor the “Wild Child,” who was abandoned as a baby in 18th century France and not discovered until he was 12, and Genie, a child whose parents kept her locked away from 18 months until 13 years of age, are two examples of children who were deprived of language. Both children made some progress in socialization after they were rescued, but neither of them ever developed a working understanding of language (Rymer, 1993). Yet, such case studies are fraught with many confounds. How much did the years of social isolation and malnutrition contribute to their problems in language development?

A better test for the notion of critical periods for language is found in studies of children with hearing loss. Several studies show that the earlier children are diagnosed with hearing impairment and receive treatment, the better the child’s long-term language development. For instance, Stika et al. (2015) reported that when children’s hearing loss was identified during newborn screening and subsequently addressed, the majority showed normal language development when later tested at 12-18 months. Fitzpatrick et al. (2011) reported that early language intervention in children who were moderately to severely hard of hearing, demonstrated normal outcomes in language proficiency by 4 to 5 years of age. Tomblin et al. (2015) reported that children who were fit with hearing aids by 6 months of age showed good levels of language development by age 2. Those whose hearing was not corrected until after 18 months showed lower language performance, even in the early preschool years. However, this study did reveal that those whose hearing was corrected by toddlerhood had greatly improved language skills by age 6. The research with hearing impaired children reveals that this critical period for language development is not exclusive to infancy, and that the brain is still receptive to language development in early childhood. Fortunately, it is has become routine to screen hearing in newborns, because when hearing loss is not treated early, it can delay spoken language, literacy, and impact children’s social skills (Moeller & Tomblin, 2015).

Learning theory

Perhaps the most straightforward explanation of language development is that it occurs through the principles of learning, including association and reinforcement (Skinner, 1953). Additionally, Bandura (1977) described the importance of observation and imitation of others in learning language. There must be at least some truth to the idea that language is learned through environmental interactions or nurture. Children learn the language that they hear spoken around them rather than some other language. Also supporting this idea is the gradual improvement in language skills over time. It seems that children modify their language through imitation and reinforcement, such as parental praise and being understood. For example, when a two-year-old child asks for juice, he might say, “me juice,” to which his mother might respond by giving him a cup of apple juice. However, language cannot be entirely learned. For one, children learn words too fast for them to be learned through reinforcement. Between the ages of 18 months and 5 years, children learn up to 10 new words every day (Anglin, 1993). More importantly, language is more generative than it is imitative. Language is not a predefined set of ideas and sentences that we choose when we need them, but rather a system of rules and procedures that allows us to create an infinite number of statements, thoughts, and ideas, including those that have never previously occurred. When a child says that she “swimmed” in the pool, for instance, she is showing generativity. No adult speaker of English would ever say “swimmed,” yet it is easily generated from the normal system of producing language.

Other evidence that refutes the idea that all language is learned through experience comes from the observation that children may learn languages better than they ever hear them. Deaf children whose parents do not communicate using ASL very well nevertheless are able to learn it perfectly on their own and may even make up their own language if they need to (Goldin-Meadow & Mylander, 1998). A group of deaf children in a school in Nicaragua, whose teachers could not sign, invented a way to communicate through made-up signs (Senghas et al., 2005). The development of this new Nicaraguan Sign Language has continued and changed as new generations of students have come to the school and started using the language. Although the original system was not a real language, it is becoming closer and closer every year, showing the development of a new language in modern times.

Social pragmatics

Another view emphasizes the very social nature of human language. Language from this view is not only a cognitive skill, but also a social one. Language is a tool humans use to communicate, connect to, influence, and inform others. Most of all, language comes out of a need to cooperate. The social nature of language has been demonstrated by a number of studies showing that children use several pre-linguistic skills (such as pointing and other gestures) to communicate not only their own needs, but what others may need. So, a child watching her mother search for an object may point to the object to help her mother find it. Eighteen-month to 30-month-olds have been shown to make linguistic repairs when it is clear that another person does not understand them (Grosse et al., 2010). Grosse et al. (2010) found that even when the child was given the desired object, if there had been any misunderstanding along the way (such as a delay in being handed the object, or the experimenter calling the object by the wrong name), children will make linguistic repairs. This would suggest that children are using language not only as a means of achieving some material goal, but also to make themselves understood in the mind of another person.

Try It

References (Click to expand)

Anglin, J. M. (1993). Vocabulary development: A morphological analysis. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 58 , v–165.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1972). Language and mind. Harcourt Brace.

Evans, N., & Levinson, S. C. (2009). The myth of language universals: Language diversity and its importance for cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 32(5), 429–448.

Fitzpatrick, E.M., Crawford, L., Ni, A., & Durieux-Smith, A. (2011). A descriptive analysis of language and speech skills in 4-to-5-yr-old children with hearing loss. Ear and Hearing, 32(2), 605-616.

Gleitman, L. R., & Newport, E. L. (1995). The invention of language by children: Environmental and biological influences on the acquisition of language. An Invitation to Cognitive Science, 1, 1-24.

Goldin-Meadow, S., & Mylander, C. (1998). Spontaneous sign systems created by deaf children in two cultures. Nature, 391(6664), 279–281.

Grosse, G., Behne, T., Carpenter, M., & Tomasello, M. (2010). Infants communicate in order to be understood. Developmental Psychology, 46(6), 1710-1722.

Lenneberg, E. (1967). Biological foundations of language. John Wiley & Sons.

Moeller, M.P., & Tomblin, J.B. (2015). An introduction to the outcomes of children with hearing loss study. Ear and Hearing, 36 Suppl (0-1), 4S-13S.

Penfield, W., & Roberts, L. (1959). Speech and brain mechanisms. Princeton University Press.

Rymer, R. (1993). Genie: A scientific tragedy. Penguin.

Senghas, R. J., Senghas, A., & Pyers, J. E. (2005). The emergence of Nicaraguan Sign Language: Questions of development, acquisition, and evolution. In S. T. Parker, J. Langer, & C. Milbrath (Eds.), Biology and knowledge revisited: From neurogenesis to psychogenesis (pp. 287–306). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Free Press.

Stika, C.J., Eisenberg, L.S., Johnson, K.C. Henning, S.C., Colson, B.G., Ganguly, D.H., & DesJardin, J.L. (2015). Developmental outcomes of early-identified children who are hard of hearing at 12 to 18 months of age. Early Human Development, 9(1), 47-55.

Stork, F. C., & Widdowson, J. D. A. (1974). Learning about linguistics: An introductory workbook.

Tomblin, J. B., Harrison, M., Ambrose, S. E., Walker, E. A., Oleson, J. J., & Moeller, M. P. (2015). Language outcomes in young children with mild to severe hearing loss. Ear and hearing, 36 Suppl 1(0 1), 76S–91S.

Werker, J. F., & Tees, R. C. (2002). Cross-language speech perception: Evidence for perceptual reorganization during the first year of life. Infant Behavior and Development, 25, 121-133.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

CC Licensed Content

“Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0

“Language & Cognition” by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0 license.

Media Attributions

- Noam_Chomsky_ © Augusto Starita is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- brocasarea © Lally & Valentine-French is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- VictorofAveyron © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- B.F._Skinner_at_Harvard_circa_1950 © Silly rabbit is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 339px-Albert_Bandura_Psychologist © Albert Bandura is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license