14.2 Post-Secondary Education

Learning Objectives

- Describe current trends in post-secondary education

- Give pros and cons of attending college

- Explain why middle adulthood may be a period with strong educational attainment

- Describe ways education can benefit older adults

Current Trends in Post-Secondary Education

According to the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems (NCHEMS) (2016a, 2016b, 2016c, 2016d), in the United States:

- 84% of 18 to 24 year olds and 88% of those 25 and older have a high school diploma or its equivalent

- 36% of 18 to 24 year olds and 7% of 25 to 49 year olds attend college

- 59% of those 25 and older have completed some college

- 32.5% of those 25 and older have a bachelor’s degree or higher, with slightly more women (33%) than men (32%) holding a college degree (Ryan & Bauman, 2016).

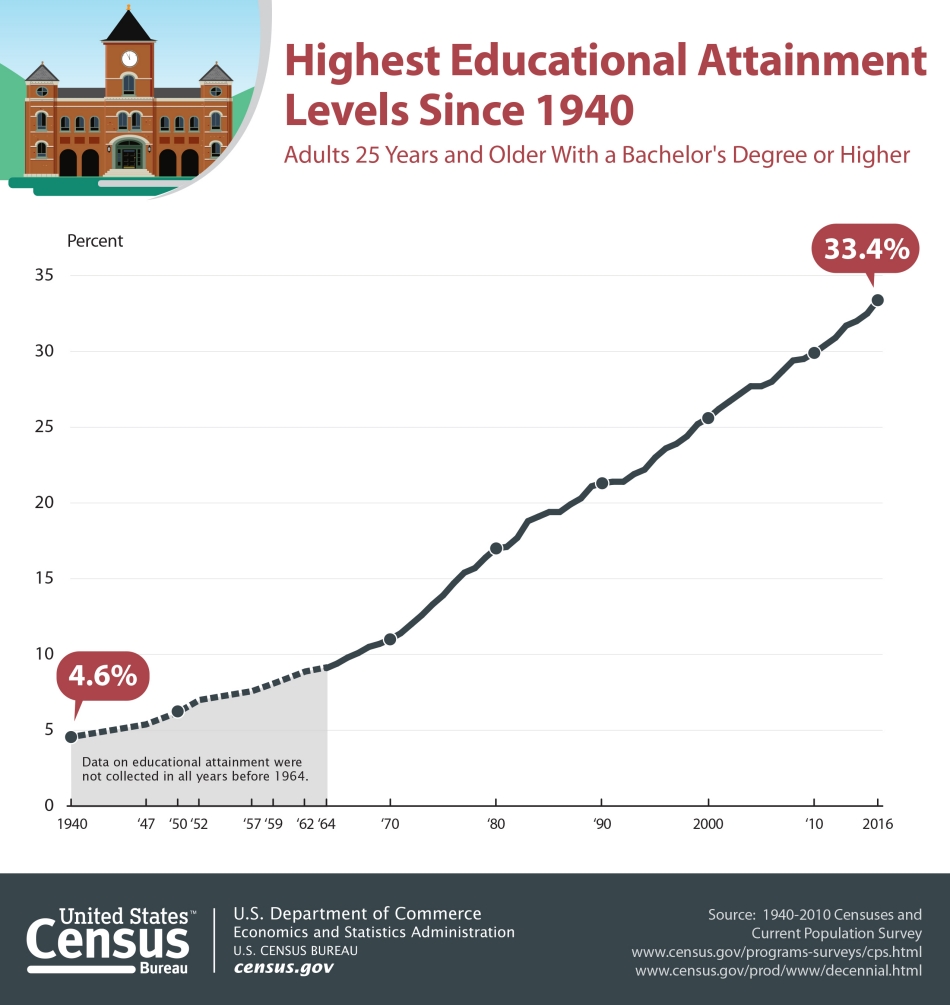

According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2017), 90 percent of the American population 25 and older have completed high school or higher level of education—compare this to just 24 percent in 1940! Each generation tends to earn (and perhaps need) increased levels of formal education. As we can see in the graph, approximately one-third of the American adult population has a bachelor’s degree or higher, as compared with less than 5 percent in 1940. Educational attainment rates vary by gender and race. All races combined, women are slightly more likely to have graduated from college than men; that gap widens with graduate and professional degrees. However, wide racial disparities still exist. For example, 23 percent of African-Americans have a college degree and only 16.4 percent of Hispanic Americans have a college degree, compared to 37 percent of non-Hispanic white Americans. The college graduation rates of African-Americans and Hispanic Americans have been growing in recent years, however (the rate has doubled since 1991 for African-Americans and it has increased 60 percent in the last two decades for Hispanic-Americans).

Try It

The rate of college attainment has grown more slowly in the United States than in a number of other nations in recent years (OCED, 2014). This may be due to fact that the cost of attaining a degree is higher in the U.S. than in most other nations.

Among the class of 2020, the likelihood of having student loan debt varied by state and ranged from 39% to 73% (The Institute for College Access & Success (TICAS), 2021). The average debt was more than $30,000 in half of all US states.

According to the most recent TICAS annual report (2021), the rate of debt varied widely across states, as well as between colleges. The after graduation debt ranged from $18,350 in Utah to $39,950 in New Hampshire. Low-debt states are mainly in the West, and high-debt states in the Northeast. In recent years there has been a concern about students carrying more debt and being more likely to default when attending for-profit institutions. In 2016, students at for-profit schools borrowed an average of $39,900, which was 41% higher than students at non-profit schools that year. In addition, 30% of students attending for-profit colleges default on their federal student loans. In contrast, the default level of those who attended public institutions is only 4% (TICAS, 2018).

College student debt has become a key political issue at both the state and federal level, and some states have been taking steps to increase spending and grants to help students with the cost of college. However, 15% of the Class of 2017’s college debt was owed to private lenders (TICAS, 2018). Such debt has less consumer protection, fewer options for repayment, and is typically negotiated at a higher interest rate.

Link to Learning

What do you think – is college really necessary? Is it worth the investment? Read the article “Is College Necessary?” from Psychology Today geared towards parents who can help their teenager decide if college is right for them.

Graduate School

Larger amounts of student debt actually occur at the graduate level (Kreighbaum, 2019). In 2019, the highest average debts were concentrated in the medical fields. Average median debt for graduate programs included:

- $42,335 for a master’s degree

- $95,715 for a doctoral degree

- $141,000 for a professional degree (including medical school)

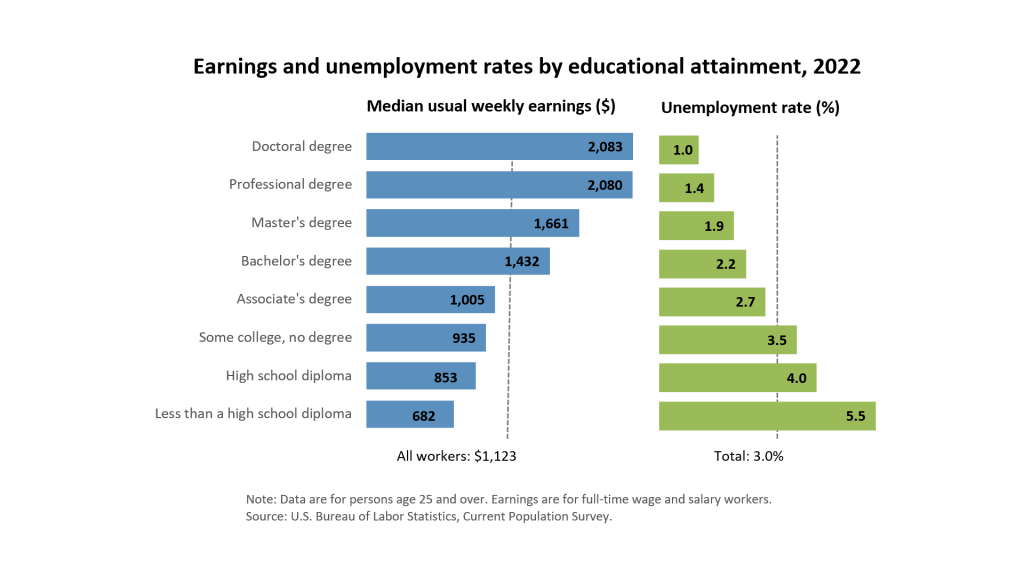

Worldwide, over 80% of college educated adults are employed, compared with just over 70% of those with a high school or equivalent diploma, and only 60% of those with no high school diploma (OECD, 2015). Those with a college degree will earn more over the course of their life time. Moreover, the benefits of college education go beyond employment and finances. The OECD found that around the world, adults with higher educational attainment were more likely to volunteer, felt they had more control over their lives, and thus were more interested in the world around them. Studies of U.S. college students find that they gain a more distinct identity and become more socially competent and less dogmatic and ethnocentric compared to those not in college (Pascarella, 2006).

Links to Learning

This article illustrates a Participatory Action Research initiative that examines the experiences of students with disabilities as they transition to college.

This article discusses college campus racial climate and how microaggressions play a key role.

Is college worth the time and investment?

College is certainly a substantial investment each year, with the financial burden falling on students and their families in the U.S., and covered mainly by the government in many other nations. Nonetheless, the benefits both to the individual and the society outweighs the initial costs. As can be seen in Figure 14.8, those in America with the most advanced degrees earn the highest income and have the lowest unemployment.

Education in Middle Adulthood

Midlife adults in the United States often find themselves in university classrooms. In fact, the rate of enrollment for older Americans entering college, often part-time or in the evenings, is rising faster than that of traditionally aged students. Students over age 35 accounted for 5% of all full-time college students and 18% of all part-time college students in fall 2019 (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022). In some cases, older students are developing skills and expertise in order to launch a second career, or to take their career in a new direction. Whether they enroll in school to sharpen particular skills, to retool and reenter the workplace, or to pursue interests that have previously been neglected, older students tend to approach the learning process differently than younger college students (Knowles, Holton, & Swanson, 1998).

The mechanics of cognition, such as working memory and speed of processing, gradually decline with age. However, they can be easily compensated for through the use of higher order cognitive skills, such as forming strategies to enhance memory or summarizing and comparing ideas rather than relying on rote memorization (Lachman, 2004). Although older students may take a bit longer to learn material, they are less likely to forget it as quickly. Adult learners tend to look for relevance and meaning when learning information. Older adults have the hardest time learning material that is meaningless or unfamiliar. They are more likely to ask themselves, “Why is this important?” when being introduced to information or when trying to memorize concepts or facts.

Older adults are more task-oriented learners and want to organize their activity around problem-solving or making contributions to real world issues. Rubin et al. (2018) surveyed university students aged 17-70 regarding their satisfaction and approach to learning in college. Results indicated that older students were more independent, inquisitive, and intrinsically motivated compared to younger students. Additionally, older women processed information at a deeper learning level and expressed more satisfaction with their education. Just as at younger ages, during middle adulthood, more women than men are likely to attend and graduate from college.

To address the educational needs of those over 50, The American Association of Community Colleges (2016) developed the Plus 50 Initiative that assists community colleges in creating or expanding programs that focus on workforce training and new careers for the plus-50 population. Since 2008 the program has provided grants for programs in 138 community colleges affecting over 37, 000 students. The participating colleges offer workforce training programs that prepare 50 plus adults for careers such as early childhood educators, certified nursing assistants, substance abuse counselors, adult basic education instructors, and human resources specialists. These training programs are especially beneficial because 80% of people over the age of 50 say they will retire later in life than their parents or continue to work in retirement, including work in a new field.

Education in Late Adulthood

Nearly 26% of people over 65 have a bachelors or higher degree (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018), but attending college is not just for the young as discussed in the previous chapter. There are many reasons why someone in late adulthood chooses to attend college. PNC Financial Services surveyed retirees aged 70 and over and found that 58% indicated that they had retired before they had planned (Holland, 2014). Many of these individuals chose to pursue additional training to improve skills to return to work in a second career. Others may be looking to take their career in a new direction. For some older students who no longer are focus on financial reasons, returning to school is intended to enable them to pursue work that is personally fulfilling. Attending college in late adulthood is also a great way for seniors to stay young and keep their minds sharp. Even if an elder chooses not to attend college for a degree, there are many continuing education programs on topics of interest available. In 1975, a nonprofit educational travel organization called Elderhostel began in New Hampshire with five programs for several hundred retired participants (DiGiacomo, 2015). This program combined college classroom time with travel tours and experiential learning experiences. In 2010 the organization changed its name to Road Scholar, and it now serves 100,000 people per year in the U.S. and in 150 countries. Academic courses, as well as practical skills such as computer classes, foreign languages, budgeting, and holistic medicines, are among the courses offered. Older adults who have higher levels of education are more likely to take continuing education. However, offering more educational experiences to a diverse group of older adults, including those who are institutionalized in nursing homes, can bring enhance the quality of life.

References (Click to expand)

American Association of Community Colleges (2016). Plus 50 community colleges: Ageless learning. Retrieved from http://plus50.aacc.nche.edu/Pages/Default.aspx

DiGiacomo, R. (2015). Road scholar, once elderhostel, targets boomers. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/nextavenue/2015/10/05/road-scholar-once-elderhostel-targets-boomers/#fcb4f5b64449

Holland, K. (2014). Why America’s campuses are going gray? Retrieved from http://www.cnbc.com/2014/08/28/why-americascampuses-are-going-gray.html

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (1998). The adult learner: A neglected species. Houston: Gulf Pub., Book Division.

Kreighbaum, A. (2019). Six figures in debt for a master’s degree. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/06/03/updated-college-scorecard-puts-spotlight-graduate-studentborrowing

Lachman, M. E. (2004). Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 305-331.

NCHEMS. (2016a). Percent of adults 18 to 24 with a high school diploma. National Center for Higher Education Management Systems http://www.higheredinfo.org/dbrowser/?level=nation&mode=graph&state=0&submeasure=344

NCHEMS. (2016b). Percent of adults 18 to 24 who are attending college. National Center for Higher Education Management Systems. Retrieved from: http://www.higheredinfo.org/dbrowser/index.php?submeasure=331&year=2009&level=nation&mode=graph&state=0

NCHEMS. (2016c). Percent of adults 25 to 49 who are attending college. National Center for Higher Education Management Systems. Retrieved from: http://www.higheredinfo.org/dbrowser/index.php?submeasure=332&year=2009&level=nation&mode=graph&state=0

NCHEMS. (2016d). Percent who earn a Bachelor’s degree within 6 years. National Center for Higher Education Management Systems. Retrieved from http://www.higheredinfo.org/dbrowser/?level=nation&mode=graph&state=0&submeasure=27

National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Characteristics of Postsecondary Students. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved July 20, 2023, from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/csb.

OECD. (2014). Education at a Glance 2014: United States, OECD Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/unitedstates/United%20States-EAG2014-Country-Note.pdf OECD. (2015). Education at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2015-en

Pascarella, E.T. (2006). How college effects students: Ten directions for future research. Journal of College Student Development, 47, 508-520.

Rubin, M., Scevak, J., Southgate, E., Macqueen, S., Williams, P., & Douglas, H. (2018). Older women, deeper learning, and greater satisfaction at university: Age and gender predict university students’ learning approach and degree satisfaction. Diversity in Higher Education, 11(1), 82-96.

Ryan, C. L. & Bauman, K. (March 2016). Educational Attainment in the United States: 2015. U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p20-578.pdf

TICAS. (2018). Student debt and the class of 2017, The Institute for College Access & Success. Retrieved from https://ticas.org/affordability-2/student-debt-and-class-2017/

TICAS. (2021). Student debt and the class of 2020, The Institute for College Access & Success. Retrieved from https://ticas.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/classof2020.pdf

US Census Bureau (2017, March). Highest Educational Levels Reached by Adults in the U.S. Since 1940. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2017/cb17-51.html

United States Census Bureau. (2018, August 03). Newsroom. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2017/cb17-ff08.html

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018, April 26). College Enrollment and Work Activity of High School Graduates New Release. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/hsgec_04262018.htm

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

CC Licensed Content

- “Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0

- Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- “Education and Work” by Margaret Clark-Plaskie for Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology by Laura Overstreet is licensed under a CC BY: Attribution

All Rights Reserved Content

- Highest Educational Levels Reached by Adults in the U.S. Since 1940. Provided by: U.S. Census Bureau. Located at: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2017/comm/cb17-51_educational_attainment.html. License: All Rights Reserved

Media Attributions

- Earnings and unemployment rates by educational attainment, 2022 by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics