16.2 Work and Careers in Adulthood

Learning Objectives

- Describe work-related issues in midlife

- Explain the role of volunteering in well-being in later adulthood

- Describe the process of retirement

Work and Careers in Middle Adulthood

Climate in the Workplace for Middle-aged Adults

A number of studies have found that job satisfaction tends to peak in middle adulthood (Besen et al., 2013; Easterlin, 2006). This satisfaction stems not only from higher wages, but also often from greater involvement in decisions that affect the workplace as middle aged adults move up from worker to supervisor or manager. Job satisfaction is also influenced by being able to do the job well, and after years of experience at a job many people are more effective and productive. Another reason for this peak in job satisfaction is that at midlife many adults lower their expectations and goals (Tangri et al., 2003). Middle-aged employees may realize that they have arrived at the highest level they are likely to reach in their career. This satisfaction at work translates into lower absenteeism, greater productivity, and less job hopping in comparison to younger adults (Easterlin, 2006).

However, not all middle-aged adults are happy in the workplace. Women may find themselves bumping up against the glass ceiling. This may explain why females employed at large corporations are twice as likely to quit their jobs as are men (Barreto et al., 2009). Another problem older workers may encounter is job burnout, defined as unsuccessfully managed workplace stress (World Health Organization, 2019). Burnout consists of:

- Feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion

- Increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of job negativism or cynicism

- Reduced feelings of professional effectiveness or efficacy

American workers may experience burnout more often than workers in many other developed nations, because most developed nations guarantee by law a set number of paid vacation days (International Labour Organization, ILO, 2011), whereas the United States does not (U.S. Department of Labor, 2016).

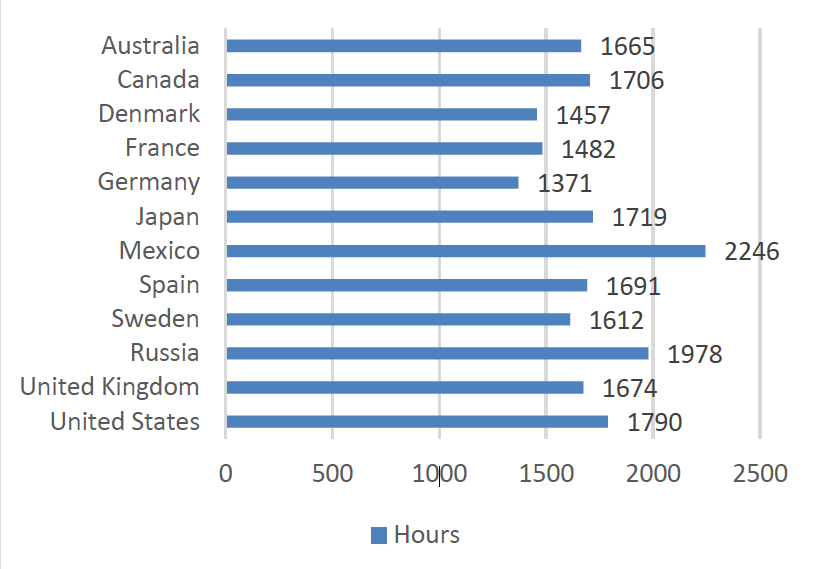

In addition, in comparision to workers in many other developed nations, American workers work more hours per year (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, OECD, 2016). Not all employees in the US are covered under overtime pay laws (U.S. Department of Labor, 2016). This is important when you considered that the 40-hour work week is a myth for most Americans. Only 4 in 10 U.S. workers work the typical 40-hour work week. The average work week for many is almost a full day longer (47 hours), with 39% working 50 or more hours per week (Saad, 2014). As can be seen in Figure 16.3, Americans work more hours than most European nations, especially western and northern Europe, although they work fewer hours than workers in other nations, especially Mexico.

Watch It

This Ted Talk discusses how working-class people can organize and own the businesses they work for, making decisions for themselves and enjoying the fruits of their labor.

Challenges in the Workplace for Middle-aged Adults

In recent years middle aged adults have been challenged by economic downturns, starting in 2001, and again in 2008 and 2020. During the recession of 2008, fifty-five percent of adults reported some problems in the workplace, such as fewer hours, pay-cuts, having to switch to part-time, etc. (Pew Research Center, 2010a). While young adults took the biggest hit in terms of levels of unemployment, middle-aged adults also saw their overall financial resources suffer as their retirement nest eggs disappeared and house values shrank, while foreclosures increased (Pew Research Center, 2010b). Not surprisingly, this age group, especially those age 50-64, reported that the recession hit them worse than did other age groups.

Middle-aged adults who find themselves unemployed are likely to remain so longer than those in early adulthood (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2012). Agism is a common complaint in the workplace. For example, in the eyes of employers, it may seem more cost effective to hire a young adult, despite their limited experience, as they would be starting out at lower levels on the pay scale. In addition, hiring someone who is 25 and has many years of work ahead of them versus someone who is 55 and will likely retire in 10 years may also be part of the decision to hire a younger worker (Lachman, 2004). It may surprise employers to learn that older workers typically stay on the job longer, as younger workers are more geographically mobile and more likely to switch jobs as more attractive opportunities appear. Older adults also demonstrate lower rates of absenteeism and greater investment in their work. American workers are also competing with global markets and changes in technology. Those who are able to keep up with all these changes or are willing to uproot and move around the country or even the world have a better chance of finding work. The decision to move may be easier for people who are younger and have fewer obligations to others.

Watch It

This Ted Talk discusses ways to cultivate inclusion and encourage diversity in the workplace.

Work, Volunteering, and Retirement in Late Adulthood

Productivity in Work

Some older people continue to be productive in work. Mandatory retirement is now illegal in the United States. However, many do choose retirement by age 65. Most people leave work by choice, and the primary factors that influence decisions about when to retire are health status, finances, and satisfaction at work. Those who do leave by choice adjust to retirement more easily. Chances are, they have prepared for a smoother transition by gradually giving more attention to an avocation or interest as they approach retirement. And they are more likely to be financially ready to retire. Those who must leave abruptly for health reasons or because of layoffs or downsizing have a more difficult time adjusting to their new circumstances. Men, especially, can find unexpected retirement difficult.

Women may feel less of an identify loss after retirement because much of their identity may have come from family roles as well. At the same time, however, women tend to have poorer retirement funds accumulated from work and if they take their retirement funds in a lump sum (be that from their own or from a deceased husband’s funds), are more at risk of outliving those funds. Because they will on average live longer, women need better financial planning in retirement. Nearly nine percent of adults over 75 were in the labor force in 2020, and this percentage is expected to increase to 11.7% in 2030 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021). Many adults 65 and older continue to work either full-time or part-time either for income or pleasure or both. In 2003, 39% of full-time workers over 55 were women over the age of 70; 53% were men over 70. This increase in numbers of older adults is likely to mean that more will continue to part of the workforce in years to come (He, et al., 2005).

Volunteering: Face-to-face and Virtually

About 40% of older adults are involved in some type of structured, face-to-face, volunteer work. But many older adults, about 60%, engage in a sort of informal type of volunteerism, helping out neighbors or friends rather than working in an organization (Berger, 2005). They may help a friend by taking them somewhere or shopping for them, etc. Some do participate in organized volunteer programs but interestingly enough, those who do tend to work part-time as well. Those who retire and do not work are less likely to feel that they have a contribution to make. (It’s as if when one gets used to staying at home, one’s confidence to go out into the world diminishes.) And those who have recently retired are more likely to volunteer than those over 75 years of age. New opportunities exist for older adults to serve as virtual volunteers by dialoguing online with others from around their world and sharing their support, interests, and expertise. According to an article from the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), virtual volunteerism has increased from 3,000 participants in 1998 to over 40,000 in 2005. These volunteer opportunities range from helping teens with their writing to communicating with ‘neighbors’ in villages in developing countries. Virtual volunteering is available to those who cannot engage in face-to-face interactions and opens up a new world of possibilities and ways to connect, maintain identity, and be productive (Uscher, 2006).

Retirement

Transitioning into Retirement

For most Americans, retirement is a process and not a one-time event (Quinn & Cahill, 2016). Sixty percent of workers transition straight to bridge jobs, which are often part-time, and occur between a career and full retirement. About 15% of workers get another job after being fully retired. This may be due to not having adequate finances after retirement or not enjoying their retirement. Some of these jobs may be in encore careers, or work in a different field from the one in which they retired. Approximately 10% of workers begin phasing into retirement by reducing their hours. However, not all employers will allow this due to pension regulations.

Retirement age changes

Looking at retirement data, the average age of retirement declined from more than 70 in 1910 to age 63 in the early 1980s. However, this trend has reversed and the current average age is now 65. Additionally, 18.5% of those over the age of 65 continue to work (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2012) compared with only 12% in 1990 (U. S. Government Accountability Office, 2011). With individuals living longer, once retired the average amount of time a retired worker collects social security is approximately 17-18 years (James et al., 2016).

When to retire

Laws often influence when someone decides to retire. In 1986 the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) was amended, and mandatory retirement was eliminated for most workers (Erber & Szuchman, 2015). Pilots, air traffic controllers, federal law enforcement, national park rangers, and fire fighters continue to have enforced retirement ages. Consequently, for most workers they can continue to work if they choose and are able. Social security benefits also play a role. For those born before 1938, they can receive full social security benefits at age 65. For those born between 1943 and 1954, they must wait until age 66 for full benefits, and for those born after 1959 they must wait until age 67 (Social Security Administration, 2016). Extra months are added to those born in years between. For example, if born in 1957, the person must wait until 66 years and 6 months. The longer one waits to receive social security, the more money will be paid out. Those retiring at age 62, will only receive 75% of their monthly benefits. Medicare health insurance is another entitlement that is not available until one is aged 65.

Delayed Retirement

Older adults primarily choose to delay retirement due to economic reasons (Erber & Szchman, 2015). Financially, continuing to work provides not only added income, but also does not dip into retirement savings which may not be sufficient. Historically, there have been three parts to retirement income; that is, social security, a pension plan, and individual savings (Quinn & Cahill, 2016). With the 2008 recession, pension plans lost value for most workers. Consequently, many older workers have had to work later in life to compensate for absent or minimal pension plans and personal savings. Social security was never intended to replace full income, and the benefits provided may not cover all the expenses, so elders continue to work. Unfortunately, many older individuals are unable to secure later employment, and those especially vulnerable include persons with disabilities, single women, the oldestold, and individuals with intermittent work histories. Some older adults delay retirement for psychological reasons, such as health benefits and social contacts. Recent research indicates that delaying retirement has been associated with helping one live longer. When looking at both healthy and unhealthy retirees, a one-year delay in retiring was associated with a decreased risk of death from all causes (Wu et al., 2016). When individuals are forced to retire due to health concerns or downsizing, they are more likely to have negative physical and psychological consequences (Erber & Szuchman, 2015).

Retirement Stages

Atchley (1994) identified several phases that individuals ago through when they retire:

- Remote pre-retirement phase includes fantasizing about what one wants to do in retirement

- Immediate pre-retirement phase when concrete plans are established

- Actual retirement

- Honeymoon phase when retirees travel and participate in activities they could not do while working

- Disenchantment phase when retirees experience an emotional let-down

- Reorientation phase when the retirees attempt to adjust to retirement by making less hectic plans and getting into a regular routine

Not everyone goes through every stage, but this model demonstrates that retirement is a process.

Post-Retirement

Those who look most forward to retirement and have plans are those who anticipate adequate income (Erber & Szuchman, 2015). This is especially true for males who have worked consistently and have a pension and/or adequate savings. Once retired, staying active and socially engaged is important. Volunteering, caregiving and informal helping can keep seniors engaged. Kaskie et al. (2008) found that 70% of retirees who are not involved in productive activities spent most of their time watching TV, which is correlated with negative affect. In contrast, being productive improves well-being.

Watch It

Seeking job enjoyment may account for the fact that many people over 50 sometimes seek changes in employment known as “encore careers.” Some midlife adults anticipate retirement, while others may be postponing it for financial reasons, or others may simple feel a desire to continue working.

References (Click to expand)

Atchley, R. C. (1994). Social forces and aging (7th ed.). Wadsworth

Barreto, M., Ryan, M. K., & Schmitt, M. T. (2009). The glass ceiling in the 21st century: Understanding the barriers to gender equality. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Berger, K. S. (2005). The developing person through the life span (6th ed.). Worth.

Besen, E., Matz-Costa, C., Brown, M., Smyer, M. A., & Pitt-Catsouphers, M. (2013). Job characteristics, core self-evaluations, and job satisfaction. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 76(4), 269-295.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, The Economics Daily, Number of people 75 and older in the labor force is expected to grow 96.5 percent by 2030 at https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2021/number-of-people-75-and-older-in-the-labor-force-is-expected-to-grow-96-5-percent-by-2030.htm (visited July 20, 2023).

Easterlin, R. A. (2006). Life cycle happiness and its sources: Intersections of psychology, economics, and demography. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27, 463-482.

Erber, J. T., & Szuchman, L. T. (2015). Great myths of aging. John Wiley & Sons.

He, W., Sengupta, M., Velkoff, V., & DeBarros, K. (2005.). U. S. Census Bureau, Current Popluation Reports, P23-209, 65+ in the United States: 2005 (United States, U. S. Census Bureau). Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p23- 190/p23-190.html

International Labour Organization. (2011). Global Employment Trends: 2011. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/@publ/documents/publication/wcms_150440.pdf

James, J. B., Matz-Costa, C., & Smyer, M. A. (2016). Retirement security: It’s not just about the money. American Psychologist, 71(4), 334-344.

Kaskie, B., Imhof, S., Cavanaugh, J., & Culp, K. (2008). Civic engagement as a retirement role for aging Americans. The Gerontologist, 48, 368-377.

Lachman, M. E. (2004). Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 305-331.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2016). Average annual hours actually worked per worker. OECD Stat. Retrieved from http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=ANHRS

Pew Research Center. (2010a). How the great recession has changed life in America. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/06/30/how-the-great-recession-has-changed-life-in-america/

Pew Research Center. (2010b). Section 5: Generations and the great recession. Retrieved from http://www.people-press.org/2011/11/03/section-5-generations-and-the-great-recession/

Quinn, J. F., & Cahill, K. E. (2016). The new world of retirement income security in America. American Psychologist, 71(4), 321-333.

Saad, L. (2014). The 40 hour work week is actually longer – by 7 hours. Gallop. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/175286/hour-workweek-actually-longer-seven-hours.aspx

Social Security Administration. (2016). Retirement planner: Benefits by year of birth. Retrieved from https://www.ssa.gov/planners/retire/agereduction.html

Tangri, S., Thomas, V., & Mednick, M. (2003). Prediction of satisfaction among college-educated African American women. Journal of Adult Development, 10, 113-125.

United States Census Bureau. (2018, April 10). The Nation’s Older Population Is Still Growing, Census Bureau Reports. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2017/ cb17-100.html

United States Census Bureau. (2018, August 03). Newsroom. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2017/cb17-ff08.html

U.S. Department of Labor (2016). Vacation Leave. Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/general/topic/workhours/vacation_leave

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2012). A profile of older Americans: 2012. Retrieved from http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/Profile/2012/docs/2012profile.pdf

United States Government Accountability Office. (2011). Income security: Older adults and the 2007-2009 recession. Washington, DC: Author. United States, National Center for Health Statistics. (2002). National Vital Statistics Report, 50(16). Retrieved May 7, 2011, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/LCWK1_2000.pdf

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2012). Unemployed older workers: Many experience challenges regaining employment and face reduced retirement security. Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-445

Uscher, J. (2006, January). How to make a world of difference-without leaving home. AARP The Magazine – Feel Great. Save Money. Have Fun. Retrieved May 07, 2011, from http://www.aarpmagazine.org/lifestyl…unteering.html

World Health Organization. (2019). Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/frequently-asked-questions/burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon (visited February 2, 2024).

Wu, C., Odden, M. C., Fisher, G. G., & Stawski, R. S. (2016). Association of retirement age with mortality: a population-based longitudinal study among older adults in the USA. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. doi:10.1136/jech2015-207097

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

CC Licensed Content

- “Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0

- Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Media Attributions

- AvgHoursWorked © Lally & Valentine-French is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Boomers Find Second Act in Encore Careers (7/26/13). Provided by: NBRbizrpt. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=UMIFOSrzmNM. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License