17.2 Attachment in Adulthood

Learning Objectives

- Describe Hazan and Shaver's attachment styles of adults

- List the two dimensions of adult attachment.

- Give examples of the resulting four attachment styles.

- Explain how the difference between prospective and retrospective studies influence conclusions about early life attachments

Attachment in Young Adulthood

Hazan and Shaver (1987) described the attachment styles of adults, using the same three general categories proposed by Ainsworth’s research on young children: secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent. Hazan and Shaver developed three brief paragraphs describing the three adult attachment styles. Adults were then asked to think about romantic relationships they were in and select the paragraph that best described the way they felt, thought, and behaved in these relationships (See table, below).

Table 17.2 Attachment in Young Adulthood

| Which of the following best describes you in your romantic relationships? | |

|---|---|

| Attachment Style | Response |

| Secure | I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t often worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me. |

| Avoidant | I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, love partners want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being. |

| Anxious/Resistant | I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me or won’t stay with me. I want to merge completely with another person, and this sometimes scares people away. |

adapted from Lally & Valentine-French, 2019 and Hazan & Shaver, 1987

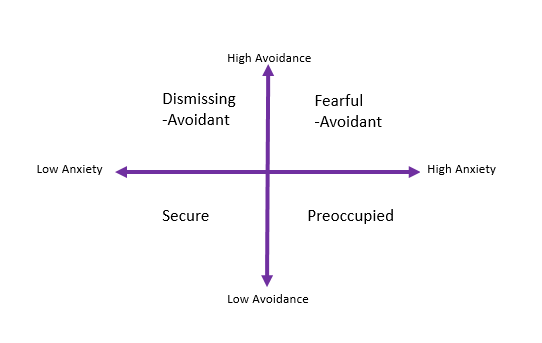

Bartholomew (1990) challenged the categorical view of attachment in adults and suggested that adult attachment was best described as varying along two dimensions; attachment related-anxiety and attachment-related avoidance. Attachment-related anxiety refers to the extent to which an adult worries about whether their partner really loves them. Those who score high on this dimension fear that their partner will reject or abandon them (Fraley et al., 2015). Attachment-related avoidance refers to whether an adult can open up to others, and whether they trust and feel they can depend on others. Those who score high on attachment-related avoidance are uncomfortable with opening up and may fear that such dependency may limit their sense of autonomy (Fraley et al., 2015). According to Bartholomew (1990) this would yield four possible attachment styles in adults; secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful-avoidant (see Figure 17.6, below.)

Securely attached adults score lower on both dimensions. They are comfortable trusting their partners and do not worry excessively about their partner’s love for them. Adults with a dismissing style score low on attachment-related anxiety, but higher on attachment-related avoidance. Such adults dismiss the importance of relationships. They trust themselves, but do not trust others, thus do not share their dreams, goals, and fears with others. They do not depend on other people and feel uncomfortable when they have to do so.

Those with a preoccupied attachment are low in attachment-related avoidance, but high in attachment-related anxiety. Such adults are often prone to jealousy and worry that their partner does not love them as much as they need to be loved. Adults whose attachment style is fearful-avoidant score high on both attachment-related avoidance and attachment-related anxiety. These adults want close relationships, but do not feel comfortable getting emotionally close to others. They have trust issues with others and often do not trust their own social skills in maintaining relationships.

Research on attachment in adulthood has found that:

- Adults with insecure attachments report lower satisfaction in their relationships (Butzer, & Campbell, 2008; Holland et al., 2012).

- Those high in attachment-related anxiety report more daily conflict in their relationships (Campbell et al., 2005).

- Those with avoidant attachment exhibit less support to their partners (Simpson et al., 2002).

- Young adults show greater attachment-related anxiety than do middle-aged or older adults (Chopik et al., 2013).

- Some studies report that young adults show more attachment-related avoidance (Schindler et al., 2010), while other studies find that middle-aged adults show higher avoidance than younger or older adults (Chopik et al., 2013).

- Young adults with more secure and positive relationships with their parents make the transition to adulthood more easily than do those with more insecure attachments (Fraley, 2013).

- Young adults with secure attachments and authoritative parents were less likely to be depressed than those with authoritarian or permissive parents or who experienced an avoidant or ambivalent attachment (Ebrahimi et al., 2017).

Do people with certain attachment styles attract those with similar styles?

When people are asked what kinds of psychological or behavioral qualities they are seeking in a romantic partner, a large majority of people indicate that they are seeking someone who is kind, caring, trustworthy, and understanding, that is, who has the kinds of attributes that characterize a “secure” caregiver (Chappell & Davis, 1998). However, we know that people do not always end up with others who meet their ideals. Are secure people more likely to end up with secure partners, and, vice versa, are insecure people more likely to end up with insecure partners? The majority of the research that has been conducted to date suggests that the answer is “yes.” Frazier et al. (1996) studied the attachment patterns of more than 83 heterosexual couples and found that, if the man was relatively secure, the woman was also likely to be secure.

One important question is whether these findings exist because (a) secure people are more likely to be attracted to other secure people, (b) secure people are likely to create security in their partners over time, or (c) some combination of these possibilities. Existing empirical research strongly supports the first alternative. For example, when people have the opportunity to interact with individuals who vary in security in a speed-dating context, they express a greater interest in those who are higher in security than those who are more insecure (McClure et al., 2010). It also is likely that secure people, who have the characteristics that many consider make an ideal partner, have their choice of partners so they select ones who are also closer to the ideal, namely, secure people. However, there is also some evidence that people’s attachment styles mutually shape one another in close relationships. For example, in a longitudinal study, Hudson et al. (2012) found that, if one person in a relationship experienced a change in security, his or her partner was likely to experience a change in the same direction.

Do early experiences as children shape adult attachment?

The majority of research on this issue is retrospective; that is, it relies on adults’ reports of what they recall about their childhood experiences. This kind of work suggests that secure adults are more likely to describe their early childhood experiences with their parents as being supportive, loving, and kind (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). A number of longitudinal studies are emerging that demonstrate prospective associations between early attachment experiences and adult attachment styles and/or interpersonal functioning in adulthood. For example, Fraley et al. (2013) found in a sample of more than 700 individuals studied from infancy to adulthood that maternal sensitivity across development prospectively predicted security at age 18. Simpson et al. (2007) found that attachment security, assessed in infancy in the strange situation, predicted peer competence in grades one to three, which, in turn, predicted the quality of friendship relationships at age 16, which, in turn, predicted the expression of positive and negative emotions in their adult romantic relationships at ages 20 to 23. You can see how positive relationships with both parents and peers contribute to higher quality relationships with romantic partners.

It is easy to come away from such findings with the mistaken assumption that early experiences “determine” later outcomes. To be clear, attachment theorists assume that the connection between early experiences and subsequent outcomes is probabilistic, not deterministic. Having supportive and responsive experiences with caregivers early in life is assumed to set the stage for positive social development, but that does not mean that attachment patterns are set in stone. In short, even if an individual has far from optimal experiences in early life, attachment theory suggests that it is possible for that individual to develop well-functioning adult relationships. People are able to rework the effects of their early experiences through a number of corrective pathways, including relationships with siblings, other family members, teachers, and close friends. Security is best viewed as an accumulation of a person’s attachment history rather than a reflection of his or her early experiences alone. Those early experiences are considered important, not because they determine a person’s fate, but because they provide the foundation for subsequent experiences.

Link to Learning

The need for intimacy, or close relationships with others, is universal and persistent across the lifespan. What our adult intimate relationships look like actually stems from infancy and our relationship with our primary caregiver (historically our mother)—a process of development described by attachment theory, which you learned about in the module on infancy. Recall that according to attachment theory, different styles of caregiving result in different relationship “attachments.”

For example, responsive mothers—mothers who soothe their crying infants—produce infants who have secure attachments (Ainsworth, 1973; Bowlby, 1969). About 60% of all children are securely attached. As adults, secure individuals rely on their working models—concepts of how relationships operate—that were created in infancy, as a result of their interactions with their primary caregiver (mother), to foster happy and healthy adult intimate relationships. Securely attached adults feel comfortable being depended on and depending on others.

As you might imagine, inconsistent or dismissive parents also impact the attachment style of their infants (Ainsworth, 1973), but in a different direction. In early studies on attachment style, infants were observed interacting with their caregivers, followed by being separated from them, then finally reunited. About 20% of the observed children were “resistant,” meaning they were anxious even before, and especially during, the separation; and 20% were “avoidant,” meaning they actively avoided their caregiver after separation (i.e., ignoring the mother when they were reunited). These early attachment patterns can affect the way people relate to one another in adulthood. Anxious-resistant adults worry that others don’t love them, and they often become frustrated or angry when their needs go unmet. Anxious-avoidant adults will appear not to care much about their intimate relationships and are uncomfortable being depended on or depending on others themselves.

Here are prototypical examples of the most highly studied attachment styles in adulthood:

- Secure: “I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t often worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me."

- Anxious-avoidant: “I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, love partners want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being.”

- Anxious-ambivalent (resistant): “I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me or won’t want to stay with me. I want to merge completely with another person, and this desire sometimes scares people away.”

The good news is that our attachment can be changed. It isn’t easy, but it is possible for anyone to “recover” a secure attachment. The process often requires the help of a supportive and dependable other, and for the insecure person to achieve coherence—the realization that their upbringing is not a permanent reflection of character or a reflection of the world at large, nor does it bar them from being worthy of love or others of being trustworthy (Treboux, Crowell, & Waters, 2004).

You can watch this video “What is Your Attachment Style?” from The School of Life to learn more.

Click here for the transcript of "What is Your Attachment Style?"

Try It

References (Click to expand)

Ainsworth, M. D. (1973). The development of infant mother attachment. In B. M. Caldwell, & H. N. Ricciuti (Eds.), Review of child development research (Vol. 3). University of Chicago Press.

Aquilino, W. S. (2006). Family relationships and support systems in emerging adulthood. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 193-217). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Armour, S. (2007, August 2). Friendships and work: A good or bad partnership? USA Today. Retrieved from http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/workplace/2007-08-01-work-friends_N.htm

Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2008). Becoming friends by chance. Psychological Science, 19(5), 439–440.

Bargh, J. A., McKenna, K. Y. A, & Fitsimons, G. G. (2002). Can you see the real me? Activation and expression of the true self on the Internet. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 33–48.

Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 147-178. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3524.61.2.226.

Benford, P. (2008). The use of Internet-based communication by people with autism (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nottingham).

Berk, Laura E. (2014). Exploring lifespan development (3rd ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Birditt, K. S., & Antonucci, T. C. (2007). Relationship quality profiles and well-being among married adults. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 595.

Blieszner, R., & Roberto, K. A. (2012). Partners and friends in adulthood. In S. K. Whitbourne & M. J. Sliwinski (Eds.), Handbooks of developmental psychology. The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of adulthood and aging (p. 381–398). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118392966.ch19

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. Attachment and Loss. Basic Books.

Brannan, D. & Mohr, C. D. (2020). Love, friendship, and social support. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/s54tmp7k

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Lewis, M. (1981). Infant social perception: Responses to pictures of parents and strangers. Developmental Psychology, 17(5), 647–649.

Butzer, B., & Campbell, L. (2008). Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships, 15, 141-154.

Campbell, L., Simpson, J. A., Boldry, J., & Kashy, D. A. (2005). Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: The role of attachment anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 510-532.

Chappell, K. D., & Davis, K. E. (1998). Attachment, partner choice, and perception of romantic partners: An experimental test of the attachment-security hypothesis. Personal Relationships, 5, 327–342.

Chopik, W. J., Edelstein, R. S., & Fraley, R. C. (2013). From the cradle to the grave: Age differences in attachment from early adulthood to old age. Journal or Personality, 81 (2), 171-183 DOI: 10.1111/j. 1467-6494.2012.00793

Cicirelli, V. (2009). Sibling relationships, later life. In D. Carr (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the life course and human development. Boston, MA: Cengage.

Collins, W. A., & Madsen, S. D. (2006). Personal Relationships in Adolescence and Early Adulthood. In A. L. Vangelisti & D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (p. 191–209). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606632.012

Davis, J. L., & Rusbult, C. E. (2001). Attitude alignment in close relationships. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 81(1), 65–84.

Deci, E. L., La Guardia, J. G., Moller, A. C., Scheiner, M. J., & Ryan, R. M. (2006). On the benefits of giving as well as receiving autonomy support: Mutuality in close friendships. Personality and social psychology bulletin, 32(3), 313-327.

Driver, J., & Gottman, J. (2004). Daily marital interactions and positive affect during marital conflict among newlywed couples. Family Process, 43, 301–314.

Dunn, J. (2007). Siblings and socialization. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization. New York: Guilford.

Ebrahimi, L., Amiri, M., Mohamadlou, M., & Rezapur, R. (2017). Attachment styles, parenting styles, and depression. International Journal of Mental Health, 15, 1064-1068.

Elsesser, L., & Peplau, L. A. (2006). The glass partition: Obstacles to cross-sex friendships at work. Human Relations, 59(8), 1077–1100.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Fehr, B. (2008). Friendship formation. In S. Sprecher, A. Wenzel, & J. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of Relationship Initiation (pp. 29–54). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Fraley, R. C., Hudson, N. W., Heffernan, M. E., & Segal, N. (2015). Are adult attachment styles categorical or dimensional? A taxometric analysis of general and relationship-specific attachment orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109 (2), 354-368.

Fraley, R. C., Roisman, G. I., Booth-LaForce, C., Owen, M. T., & Holland, A. S. (2013). Interpersonal and genetic origins of adult attachment styles: A longitudinal study from infancy to early adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 8817-838.

Frazier, P. A, Byer, A. L., Fischer, A. R., Wright, D. M., & DeBord, K. A. (1996). Adult attachment style and partner choice: Correlational and experimental findings. Personal Relationships, 3, 117–136.

Freitas, A. L., Azizian, A., Travers, S., & Berry, S. A. (2005). The evaluative connotation of processing fluency: Inherently positive or moderated by motivational context? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(6), 636–644.

Gottman, J. M. (1999). Couple's handbook: Marriage Survival Kit Couple's Workshop. Seattle, WA: Gottman Institute.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 221–233.

Gottman, J. M., Carrere, S., Buehlman, K. T., Coan, J. A., & Ruckstuhl, L. (2000). Predicting marital stability and divorce in newlywed couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 14(1), 42-58.

Harmon-Jones, E., & Allen, J. J. B. (2001). The role of affect in the mere exposure effect: Evidence from psychophysiological and individual differences approaches. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(7), 889–898.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52 (3), 511-524.

Hendrick, C., & Hendrick, S. S. (Eds.). (2000). Close relationships: A sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Holland, A. S., Fraley, R. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2012). Attachment styles in dating couples: Predicting relationship functioning over time. Personal Relationships, 19, 234-246. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01350.x

Hudson, N. W., Fraley, R. C., Vicary, A. M., & Brumbaugh, C. C. (2012). Attachment coregulation: A longitudinal investigation of the coordination in romantic partners’ attachment styles. Manuscript under review.

Janicki, D., Kamarck, T., Shiffman, S., & Gwaltney, C. (2006). Application of ecological momentary assessment to the study of marital adjustment and social interactions during daily life. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 168–172.

Kaufman, B. E., & Hotchkiss, J. L. 2003. The economics of labor markets (6th ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western.

McClure, M. J., Lydon., J. E., Baccus, J., & Baldwin, M. W. (2010). A signal detection analysis of the anxiously attached at speed-dating: Being unpopular is only the first part of the problem. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 1024–1036.

McKenna, K. A. (2008) MySpace or your place: Relationship initiation and development in the wired and wireless world. In S. Sprecher, A. Wenzel, & J. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of relationship initiation (pp. 235–247). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

McKenna, K. Y. A., Green, A. S., & Gleason, M. E. J. (2002). Relationship formation on the Internet: What’s the big attraction? Journal of Social Issues, 58, 9–31.

Mita, T. H., Dermer, M., & Knight, J. (1977). Reversed facial images and the mere-exposure hypothesis. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 35(8), 597–601.

Reis, H. T., & Aron, A. (2008). Love: What is it, why does it matter, and how does it operate? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(1), 80–86.

Riordan, C. M., & Griffeth, R. W. (1995). The opportunity for friendship in the workplace: An underexplored construct. Journal of Business and Psychology, 10, 141–154.

Schindler, I., Fagundes, C. P., & Murdock, K. W. (2010). Predictors of romantic relationship formation: Attachment style, prior relationships, and dating goals. Personal Relationships, 17, 97-105.

Sherman, A. M., De Vries, B., & Lansford, J. E. (2000). Friendship in childhood and adulthood: Lessons across the life span. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 51(1), 31-51.

Simpson, J. A., Collins, W. A., Tran, S., & Haydon, K. C. (2007). Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 355–367.

Simpson, J. A., Rholes, W. S., Oriña, M. M., & Grich, J. (2002). Working models of attachment, support giving, and support seeking in a stressful situation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 598-608.

Sternberg, R. (1988). A triangular theory of love. New York: Basic.

Tannen, D. (1990). You just don't understand: Women and men in conversation. New York: Morrow.

Zebrowitz, L. A., Bronstad, P. M., & Lee, H. K. (2007). The contribution of face familiarity to in group favoritism and stereotyping. Social Cognition, 25(2), 306–338.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

CC Licensed Content, shared previously

- "Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition" by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0

- Love, Friendship, and Social Support by Debi Brannan and Cynthia D. Mohr is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- Additional written material by Ellen Skinner & Heather Brule, Portland State University is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

- "Attraction and Love." Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Margaret Clark-Plaskie for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- The Family; section on attachment. Authored by: Joel A. Muraco . Provided by: University of Wisconsin, Green Bay. Located at: https://nobaproject.com/modules/the-family. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology. Authored by: Laura Overstreet . Located at: http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/. License: CC BY: Attribution

All Rights Reserved Content

"What is Your Attachment Style?" is licensed All Rights Reserved and is embedded here according to YouTube terms of service.

Media Attributions

- four category model is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license