18.2 The Family Life Cycle

Learning Objectives

- Identify the overarching individual objective or task of the family life cycle.

- Describe the phases of the family life cycle.

- Explain changes in marital satisfaction across the family life cycle.

- Describe a common change in marital satisfaction that accompanies the “empty nest.”

- Describe changes in gender roles across the family life cycle.

- Describe the role of grandparents in the family life cycle.

- Describe the changes in family relationships during middle adulthood.

- Describe changes and concerns in relationships with aging parents.

The family life cycle is conventionally represented as a sequence of stages typical of many adults, moving from independence from the family of origin, through forming one's own family unit, raising kids, and becoming grandparents. Of course, many people do not follow the traditional sequence or pattern shown in this conventional family life cycle. It can be useful to broaden our definition of family life so it includes all varieties of domestic arrangement. If we do, "family" encompasses most of our activities in adult life other than work, friendships, and me-time. For many people, close friends are considered part of family.

We know that some families involve intimate relationships and children, but there are also other important facets. Family life revolves around the home. An important aspect of life for every adult is where they live and who lives with them. Another aspect is "home-making"--cooking, cleaning, and maintenance. Who does what? Family life also involves doing things together and enjoying a sense of community. For most adults in most cultures, the primary organizing factor in their lives is family, hence, the phrase "family life." Much of development during adulthood revolves around where a person finds themselves in the family life cycle, in terms of moving through a sequence of finding a partner, forming a household family unit, and having or not having and raising children.

Family life cycle patterns differ across cultures and subcultures, and shift with historical time. The overarching objective or task of the family life cycle is to create the life that fits and works for the individual, that is consistent with their personal characteristics and preferences, the life they want. Successful navigation of the family life cycle means finding a life that is personally meaningful and fulfilling for you and that works for the rest of your family (however constituted) as well.

Family Transitions

Sibling relationships

When families have more than one child, the relationships between siblings cultivate a new dynamic in the family system. Siblings spend a considerable amount of time with each other and offer a unique relationship that is not found with same-age peers or with adults. Siblings play an important role in the development of social skills. Cooperative and pretend play interactions between younger and older siblings can teach empathy, sharing, and cooperation (Pike, Coldwell, & Dunn, 2005), as well as, negotiation and conflict resolution (Abuhatoum & Howe, 2013). However, the quality of sibling relationships is often mediated by the quality of the parent-child relationship and the psychological adjustment of the child (Pike et al., 2005). For instance, more negative interactions between siblings have been reported in families where parents had poor patterns of communication with their children (Brody, Stoneman, & McCoy, 1994). Children who have emotional and behavioral problems are also more likely to have negative interactions with their siblings. However, the psychological adjustment of the child can sometimes be a reflection of the parent-child relationship. Thus, when examining the quality of sibling interactions, it is often difficult to tease out the separate effect of adjustment from the effect of the parent-child relationship.

While parents want positive interactions between their children, conflicts are going to arise, and some confrontations can be the impetus for growth in children’s social and cognitive skills. The sources of conflict between siblings often depend on their respective ages. Dunn and Munn (1987) revealed that over half of all sibling conflicts in early childhood were disputes about property rights. By middle childhood this starts shifting toward control over social situations, such as what games to play, disagreements about facts or opinions, or rude behavior (Howe, Rinaldi, Jennings, & Petrakos, 2002).

Researchers have also found that the strategies children use to deal with conflict change with age, but this is also tempered by the nature of the conflict. Abuhatoum and Howe (2013) found that coercive strategies (e.g., threats) were more common when the dispute centered on property rights, while reasoning was more likely to be used by older siblings and in disputes regarding control over the social situation. However, younger siblings also use reasoning, frequently bringing up the concern of legitimacy (e.g., “You’re not the boss”) when in conflict with an older sibling. This is a very common strategy used by younger siblings and is possibly an adaptive strategy in order for younger siblings to assert their autonomy (Abuhatoum & Howe, 2013). A number of researchers have found that children who can use non-coercive strategies are more likely to have a successful resolution, whereby a compromise is reached and neither child feels slighted (Ram & Ross, 2008; Abuhatoum & Howe, 2013). Not surprisingly, friendly relationships with siblings often lead to more positive interactions with peers. The reverse is also true. A child can also learn to get along with a sibling, with, as the song says, “a little help from my friends” (Kramer & Gottman, 1992).

Sibling relationships are one of the longest-lasting bonds in people’s lives. Yet, there is little research on the nature of sibling relationships in adulthood (Aquilino, 2006). What is known is that the nature of these relationships change, as adults have a choice as to whether they will create or maintain a close bond and continue to be a part of the life of a sibling. Siblings must make the same reappraisal of each other as adults, as parents have to with their adult children. Research has shown a decline in the frequency of interactions between siblings during early adulthood, as presumably peers, romantic relationships, and children become more central to the lives of young adults. Aquilino (2006) suggests that the task in early adulthood may be to maintain enough of a bond so that there will be a foundation for this relationship in later life. Those who are successful can often move away from the “older-younger” sibling conflicts of childhood, toward a more egalitarian relationship between two adults. Siblings that were close to each other in childhood are typically close in adulthood (Dunn, 1984, 2007), and in fact, it is unusual for siblings to develop closeness for the first time in adulthood. Overall, the majority of adult sibling relationships are close (Cicirelli, 2009).

Empty nest

The empty nest, or post-parental period refers to the time period when children are grown up and have left home (Dennerstein, Dudley & Guthrie, 2002). For most parents this occurs during midlife. This time is recognized as a “normative event” as parents are aware that their children will become adults and eventually leave home (Mitchell & Lovegreen, 2009). The empty nest creates complex emotions, both positive and negative, for many parents. Some theorists suggest this is a time of role loss for parents, others suggest it is one of role strain relief (Bouchard, 2013).

The role loss hypothesis predicts that when people lose an important role in their life they experience a decrease in emotional well-being. It is from this perspective that the concept of the empty nest syndrome emerged, which refers to great emotional distress experienced by parents, typically mothers, after children have left home. The empty nest syndrome is linked to the absence of alternative roles for the parent in which they could establish their identity (Borland, 1982). In Bouchard’s (2013) review of the research, she found that few parents reported loneliness or a big sense of loss once all their children had left home.

In contrast, the role stress relief hypothesis suggests that the empty nest period should lead to more positive changes for parents, as the responsibility of raising children has been lifted. The role strain relief hypothesis was supported by many studies in Bouchard’s (2013) review. A consistent finding throughout the research literature is that raising children has a negative impact on the quality of martial relationships (Ahlborg, Misvaer, & Möller, 2009; Bouchard, 2013). Most studies report that martial satisfaction often increases during the launching phase of the empty nest period, and that this satisfaction endures long after the last child has left home (Gorchoff, John, & Helson, 2008).

However, most of the research on the post-parental period has been with American parents. A number of studies in China suggest that empty-nesters, especially in more rural areas of China, report greater loneliness and depression than their counterparts with children still at home (Wu et al., 2010). Family support for the elderly by their children is a cherished Chinese tradition (Wong & Leung, 2012). The fact that children move from the rural communities to the larger cities for education and employment may explain the more negative reaction of Chinese parents compared to American samples. The loss of an adult child in a rural region may mean a loss of family income and support for aging parents. Empty-nesters in urban regions of China did not report the same degree of distress (Su et al., 2012), suggesting that it not so much the event of children leaving, but the additional hardships this may place on aging parents.

Boomerang Kids

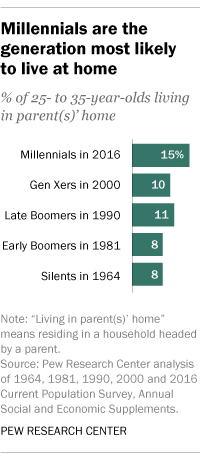

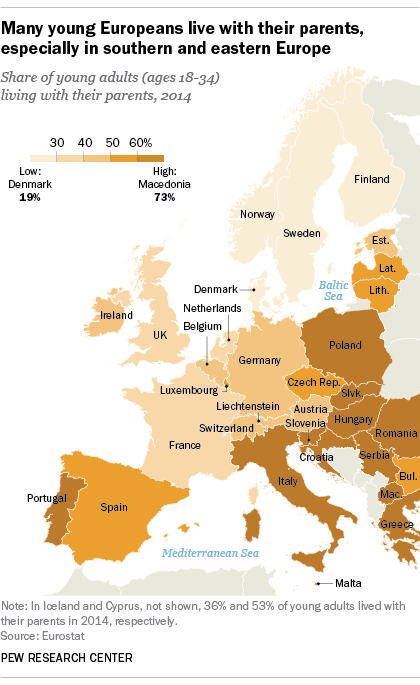

Young adults are living with their parents for a longer duration and in greater numbers than previous generations. In addition to those in early adulthood who are not leaving the home of their parents, there are also boomerang kids, a term used to refer to young adults who return after having lived independently outside the home. The first Figure 8.14 shows the number of American young people 25-35 who were living at home based on their generation (Fry, 2017). The second Figure 8.15 with the European map, shows that more young adults 18-34 in Europe are also living with their parents (Desilver, 2016). Many of the same financial reasons that are influencing young people’s decisions to delay exit from the home of their parents are underlying their decisions to return home. In addition, to financial reasons, some boomerang kids are returning because of emotional distress, such as mental health issues (Sandberg-Thoma, Snyder, & Jang, 2015).

What is the effect on parents when their adult children return home? Certainly, there is considerable research that shows that the stress of raising children can have a negative impact on parents’ well-being, and that when children leave home many couples experience less stress and greater life satisfaction (see the section on the empty nest). Early research in the 1980s and 1990s supported the notion that boomerang children, along with those who were failing to exit the home, placed greater financial hardship on the parents, and the parents reported more negative perceptions of this living arrangement (Aquilino, 1991).

Recent surveys suggest that today’s parents are more tolerant of this, perhaps because this is becoming a more normative experience than in the past. Moreover, children who return are more likely to have had good relationships with their parents growing up, so there may be less stress between parents and their adult children who return (Sandberg-Thoma et al., 2015). Parents of young adults who have moved back home because of economic reasons report that they are just as satisfied with their life as are parents whose adult children are still living independently (Parker, 2012). Parker found that adult children age 25 and older are more likely to contribute financially to the family or complete chores and other household duties. Parker also found that living in a multigenerational household may be acting as an economic safety net for young adults. In comparison to young adults who were living outside of the home, those living with their parents were less likely to be living in poverty (17% versus 10%).

Relationship with Adult Children

In early adulthood the parent-child relationship transitions by necessity toward a relationship between two adults. This involves a reappraisal of the relationship by both parents and young adults. One of the biggest challenges for parents, especially during emerging adulthood, is coming to terms with the adult status of their children. Aquilino (2006) suggests that parents who are reluctant or unable to do so may hinder young adults’ identity development. This problem becomes more pronounced when young adults still reside with their parents and are financially dependent on them. Arnett (2004) reported that leaving home often helped promote psychological growth and independence in early adulthood.

Many older adults provide financial assistance and/or housing to adult children. At this point in history, there is more support going from the older parent to the younger adult children than in the other direction (Fingerman & Birditt, 2011). In addition to providing for their own children, many elders are raising their grandchildren. Consistent with socioemotional selectivity theory, older adults seek, and are helped by, their adult children providing emotional support (Lang & Schütze, 2002). Lang and Schütze, as part of the Berlin Aging Study (BASE), surveyed adult children (mean age 54) and their aging parents (mean age 84). They found that the adult children of older parents who provided emotional support, such as showing tenderness toward their parent, cheering the parent up when he or she was sad, tended to report greater life satisfaction. In contrast, older adults whose children provided informational support, such as providing advice to the parent, reported less life satisfaction. Lang and Schütze found that older adults wanted their relationship with their children to be more emotionally meaningful, but they did not want their children telling them what to do. Daughters and adult children who were younger, tended to provide such support more than sons and adult children who were older. Lang and Schütze also found that adult children who were more autonomous rather than emotionally dependent on their parents, had more emotionally meaningful relationships with their parents, from both the parents’ and adult children’s point of view.

Linked Lives

So far, we have considered the impact that adult children who have returned home or have yet to leave the nest have on the lives of middle-aged parents. What about the effect on parents who have adult children dealing with personal problems, such as alcoholism, chronic health concerns, mental health issues, trouble with the law, poor social relationships, or academic or job-related problems, even if they are not living at home? The life course perspective proposes the idea of linked lives (Greenfield & Marks, 2006), which is the notion that people in important relationships, such as children and parents, mutually influence each other’s developmental pathways. You have read about the effects that parents have on their children’s development, but this relationship is bidirectional. The problems faced by children, even when those children are adults, influence the lives of their parents. Greenfield and Marks found in their study of middle-aged parents and their adult children, those parents whose children were dealing with personal problems reported more negative affect, lower self-acceptance, poorer parent-child interactions, and more family relationship stress. The more problems the adult children were facing, the worse the lives and emotional health of their parents, with single parents faring the worst.

Link to Learning: The Family Life Cycle

To better understand patterns of family life and the changes in roles and expectations as a family ages, researchers have theorized about typical stages of family life. Read more about the family life cycle in the following interactive activity.

Link to Learning: The Family Life Cycle

To better understand patterns of family life and the changes in roles and expectations as a family ages, researchers have theorized about typical stages of family life. Read more about the family life cycle in the following interactive activity.

Family Caregivers

A disabled child, spouse, parent, or other family member is part of the lives of some midlife adults. According to the National Alliance for Caregiving (2015), 40 million Americans provide unpaid caregiving for family members. The typical caregiver is a 49-year-old female currently caring for a 69 year-old female who needs care because of a long-term physical condition. Looking more closely at the age of the recipient of caregiving, the typical caregiver for those 18-49 years of age is a female (61%) caring mostly for her own child (32%) followed by a spouse or partner (17%). When looking at older recipients (50+) who receive care, the typical caregiver is female (60%) caring for a parent (47%) or spouse (10%).

Caregiving places an enormous burden on the caregiver, and is one of the most demanding and stressful roles that people can take on. Caregiving for a young or adult child with special needs is associated with poorer global health and more physical symptoms among both fathers and mothers (Seltzer, Floyd, Song, Greenberg, & Hong, 2011). Marital relationships are also a factor in how caregiving affects stress and chronic conditions. Fathers who were caregivers reported more chronic health conditions than non-caregiving fathers, regardless of marital quality. In contrast, caregiving mothers reported higher levels of chronic conditions when they also reported a high level of marital strain (Kang & Marks, 2014). Age can also make a difference in how one is affected by the stress of caring for a child with special needs. Using data from the Study of Midlife in the Unites States, Ha, Hong, Seltzer and Greenberg (2008) found that older parents were significantly less likely to experience the negative effects of having a disabled child than younger parents. They concluded that an age-related weakening of the stress occurred over time, as other non-disabled children became independent and left home. The general trend of greater emotional stability noted at midlife may also have played a role.

Currently 25% of adult children, mainly baby boomers, provide personal or financial care to a parent (Metlife, 2011). Daughters are more likely to provide basic care and sons are more likely to provide financial assistance. Adult children 50+ who work and provide care to a parent are more likely to have fair or poor health when compared to those who do not provide care. Some adult children choose to leave the work force to care for a parent, however, the cost of leaving the work force early is high. For females, lost wages and social security benefits equals $324,044, while for men it equals $283,716 (Metlife, 2011). This loss can jeopardize the adult child’s financial future. Consequently, there is a need for greater workplace flexibility for working caregivers.

According to the Institute of Medicine (2015), it is estimated that 66 million Americans, or 29% of the adult population, are caregivers for someone who is dying or chronically ill. Two-thirds of these caregivers are women. This care takes its toll physically, emotionally, and financially. Family caregivers may face the physical challenges of lifting, dressing, feeding, bathing, and transporting a dying or ill family member. They may worry about whether they are performing all tasks safely and properly, as they receive little training or guidance. Such caregiving tasks may also interfere with their ability to take care of themselves and meet other family and workplace obligations. Financially, families often face high out of pocket expenses (IOM, 2015).

As can be seen in the table below, most family caregivers are providing care by themselves with little professional intervention, are employed, and have provided care for more than 3 years. In 2013, the annual loss of productivity in the U.S. was $25 billion as a result of work absenteeism due to providing this care. As the prevalence of chronic disease rises, the need for family caregivers is growing. Unfortunately, the number of potential family caregivers is declining as the large baby boomer generation enters into late adulthood (Redfoot, Feinberg, & Houser, 2013).

Table 18.2 Characteristics of Family Caregivers in the United States

| Characteristic | Percentages |

|---|---|

| No home visits by health care professionals | 69% |

| Caregivers are also employed | 72% |

| Duration of employed workers who have been caregiving for 3+ years | 55% |

| Caregivers for the elderly | 67% |

adapted from Lally & Valentine-French, 2019 and IOM, 2015

Spousal Care

Certainly, caring for a disabled spouse can be a difficult experience that can negatively affect one’s health. However, research indicates that there can also be positive health effects for caring for a disabled spouse. Beach, Schulz, Yee and Jackson (2000) evaluated health related outcomes in four groups: Spouses with no caregiving needed (Group 1), living with a disabled spouse but not providing care (Group 2), living with a disabled spouse and providing care (Group 3), and helping a disabled spouse while reporting caregiver strain, including elevated levels of emotional and physical stress (Group 4). Not surprisingly, the participants in Group 4 were the least healthy and identified poorer perceived health, an increase in health-risk behaviors, and an increase in anxiety and depression symptoms. However, those in Group 3 who provided care for a spouse, but did not identify caregiver strain, actually reported decreased levels of anxiety and depression compared to Group 2 and were actually similar to those in Group 1. It appears that greater caregiving involvement was related to better mental health as long as the caregiving spouse did not feel strain. The beneficial effects of helping reported by the participants were consistent with previous research (Krause, Herzog, & Baker, 1992; Schulz et al., 1997).

When caring for a disabled spouse, gender differences have also been found. Female caregivers of a spouse with dementia experienced more burden, had poorer mental and physical health, exhibited increased depressive symptomatology, took part in fewer health-promoting activities, and received fewer hours of help than male caregivers (Gibbons et al., 2014). This study was consistent with previous research findings that women experience more caregiving burden than men, despite similar caregiving situations (Torti, Gwyther, Reed, Friedman, & Schulman, 2004; Yeager, Hyer, Hobbs, & Coyne, 2010). A primary factor contributing to women’s poorer caregiving outcomes is that disabled males are more aggressive than females, especially males with dementia who display more physical and sexual aggression toward their caregivers (Eastley & Wilcock, 1997; Zuidema, de Jonghe, Verhey, & Koopmans, 2009). Explanations for why women are not offered or do not use more external support, which may alleviate some of the burden, include society's expectations that they should assume caregiving roles (Torti et al, 2004) and women's concerns with the opinions of others (Arai, Sugiura, Miura, Washio, & Kudo, 2000). Female caregivers are certainly at risk for negative consequences of caregiving, and greater support needs to be available to them.

The Sandwich Generation

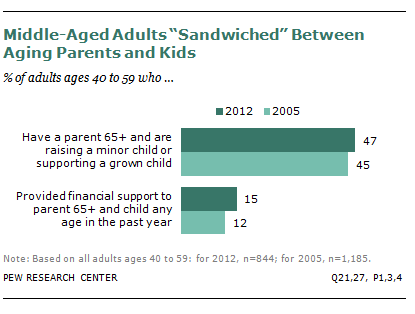

The sandwich generation refers to adults who have at least one parent age 65 or older and are either raising their own children or providing support for their grown children. According to a recent Pew Research survey, 47% of middle-aged adults are part of this sandwich generation (Parker & Patten, 2013). In addition, 15% of middle-aged adults are providing financial support to an older parent while raising or supporting their own children (see Figure 8.12). According to the same survey, almost half (48%) of middle-aged adults, have supported their adult children in the past year, and 27% are the primary source of support for their grown children.

Seventy-one percent of the sandwich generation is age 40-59, 19% were younger than 40, and 10% were 60 or older. Hispanics are more likely to find themselves supporting two generations: 31% have parents 65 or older and a dependent child, compared with 24% of whites and 21% of blacks (Parker & Patten, 2013). Women are more likely to take on the role of care provider for older parents in the U.S. and Germany (Pew Research, 2015). About 20% of women say they have helped with personal care, such as getting dressed or bathing, of aging parents in the past year, compared with 8% of men in the U.S. and 4% in Germany. In contrast, in Italy men are just as likely (25%) as women (26%) to have provided personal care.

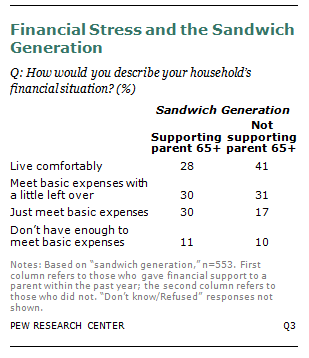

The Pew survey found that almost 33% of the sandwich-generation adults were more likely to say they always feel rushed, while only 23% of other adults said this. However, the survey suggests that those who were supporting both parents and children reported being just as happy as those middle-aged adults who did not find themselves in the sandwich generation (Parker & Patten, 2013). Adults who are supporting both parents and children did report greater financial strain (see Figure 8.13). Only 28% reported that they were living comfortably versus 41% of those who were not also supporting their parents. Almost 33% were just making ends meet, compared with 17% of those who did not have the additional financial burden of aging parents.

Grandparents

In addition to maintaining relationships with their children and aging parents, many people in middle adulthood take on yet another role, becoming a grandparent. The role of grandparent varies around the world. In multigenerational households, grandparents may play a greater role in the day-to-day activities of their grandchildren. While this family dynamic is more common in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, it has been on the increase in the U.S. (Pew Research Center, 2010). Around the world, even when not cohabitating with their children and grandchildren, grandparents are usually a major source of support for new parents and young families.

The degree of grandparent involvement depends on the proximity of the grandparents’ home to the grandchildren. In developed nations, greater societal mobility means that many grandparents live long distances from their grandchildren. Technology has brought grandparents and their more distant grandchildren together. Sorenson and Cooper (2010) found that many of the grandfathers they interviewed would text, email, or Skype with their grandchildren in order to stay in touch.

Cherlin and Furstenberg (1986) described three styles of grandparents. Thirty percent of grandparents were remote because they rarely saw their grandchildren. Usually they lived far away from the grandchildren but may also have had a distant relationship. Contact was typically made on special occasions, such as holidays or birthdays. Fifty-five percent of grandparents were described as companionate because they did things with their grandchildren but had little authority or control over them. They preferred to spend time with them without interfering in parenting. They were more like friends to their grandchildren. Fifteen percent of grandparents were described as involved because they took a very active role in their grandchild’s life. The involved grandparent had frequent contact with and authority over the grandchild, and their grandchildren might even live with them. Depending on the circumstances (which sometimes involve problems with the grandchildren's parents, such as illness or addiction), taking over the parenting role for grandchildren can be stressful or it can be rewarding, or both. Grandmothers, more so than grandfathers, played this role. In contrast, more grandfathers than grandmothers saw their role as family historian and family advisor (Neugarten and Weinstein, 1964). Bengtson (2001) suggests that grandparents adopt different styles with different grandchildren, and over time may change styles as circumstances in the family change. Today more grandparents are the sole care providers for grandchildren or may step in at times of crisis.

Try It

References (Click to expand)

AARP. (2009). The divorce experience: A study of divorce at midlife and beyond. Washington, DC: AARP

Ahlborg, T., Misvaer, N., & Möller, A. (2009). Perception of marital quality by parents with small children: A follow-up study when the firstborn is 4 years old. Journal of Family Nursing, 15, 237–263.

Allendorf, K. (2013). Schemas of marital change: From arranged marriages to eloping for love. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75, 453-469.

Alterovitz, S. S., & Mendelsohn, G. A. (2013). Relationship goals of middle-aged, young-old, and old-old Internet daters: An analysis of online personal ads. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 159–165.

Anderson, E. R., & Greene, S. M. (2011). “My child and I are a package deal”: Balancing adult and child concerns in repartnering after divorce. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(5), 741-750.

Anderson, E.R., Greene, S.M., Walker, L., Malerba, C.A., Forgatch, M.S., & DeGarmo, D.S. (2004). Ready to take a chance again: Transitions into dating among divorced parents. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 40, 61-75.

Aquilino, W. (1991). Predicting parents’ experiences with coresidence adult children. Journal of Family Issues, 12(3), 323-342.

Arai, Y., Sugiura, M., Miura, H., Washio, M., & Kudo, K. (2000). Undue concern for other’s opinions deters caregivers of impaired elderly from using public services in rural Japan. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(10), 961-968.

Beach, S. R., Schulz, R., Yee, J. L., & Jackson, S. (2000). Negative and positive health effects of caring for a disabled spouse: Longitudinal findings from the caregiver health effects study. Psychology and Aging, 15(2), 259-271.

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55, 83–96.

Bengtson, V. L. (2001). Families, intergenerational relationships, and kinkeeping in midlife. In N. M. Putney (Author) & M. E. Lachman (Ed.), Handbook of midlife development (pp. 528-579). New York: Wiley.

Benokraitis, N. V. (2005). Marriages and families: Changes, choices, and constraints (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Birditt, K. S., & Antonucci, T.C. (2012). Till death do us part: Contexts and implications of marriage, divorce, and remarriage across adulthood. Research in Human Development, 9(2), 103-105.

Borland, D. C. (1982). A cohort analysis approach to the empty-nest syndrome among three ethnic groups of women: A theoretical position. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 44, 117–129.

Bouchard, G. (2013). How do parents reaction when their children leave home: An integrative review. Journal of Adult Development, 21, 69-79.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1989). Ecological systems theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Annals of Child Development, Vol. 6 (pp. 187–251). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Brown, S. L., & Lin, I. (2013). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle aged and older adults 1990-2010. National Center for Family & Marriage Research Working Paper Series. Bowling Green State University. https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and- sciences/NCFMR/ documents/Lin/The-Gray-Divorce.pdf

Bumpass, L. L. (1990). What’s happening to the family? Interactions between demographic and institutional change. Demography, 27(4), 483–498.

Carmichael, C. L., Reis, H. T., & Duberstein, P. R. (2015). In your 20s it’s quantity, in your 30s it’s quality: The prognostic value of social activity across 30 years of adulthood. Psychology and Aging, 30(1), 95-105.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015a). Births and natality. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/births.htm

Cherlin, A. J., & Furstenberg, F. F. (1986). The new American grandparent: A place in the family, a life apart. New York: Basic Books.

Clark, L. A., Kochanska, G., & Ready, R. (2000). Mothers’ personality and its interaction with child temperament as predictors of parenting behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 274–285.

Cohen, P. (2013). Marriage is declining globally. Can you say that? Retrieved from https://familyinequality.wordpress.com/2013/06/12/marriage-is-declining/

Cohn, D. (2013). In Canada, most babies now born to women 30 and older. Pew Research Center.

Conger, R. D., & Conger, K. J. (2002). Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 361–373.

Cooke, L. P. (2010). The politics of housework. In J. Treas & S.Drobnic (Eds.), Dividing the domestic: Men, women, and household work in cross-national perspective (pp. 59-78). Standford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Copen, C.E., Daniels, K., & Mosher, W.D. (2013) First premarital cohabitation in the United States: 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National health statistics reports; no 64. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Crowley, K., Callanan, M. A., Tenenbaum, H. R., & Allen, E. (2001). Parents explain more often to boys than to girls during shared scientific thinking. Psychological Science, 12, 258–261.

Demick, J. (1999). Parental development: Problem, theory, method, and practice. In R. L. Mosher, D. J. Youngman, & J. M. Day (Eds.), Human development across the life span: Educational and psychological applications (pp. 177–199). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Dennerstein, L., Dudley, E., & Guthrie, J. (2002). Empty nest or revolving door? A prospective study of women’s quality of life in midlife during the phase of children leaving and re-entering the home. Psychological Medicine, 32, 545–550.

DePaulo, B. (2014). A singles studies perspective on mount marriage. Psychological Inquiry, 25(1), 64-68.

Desai, S., & Andrist, L. (2010). Gender scripts and age at marriage in India. Demography, 47, 667-687.

Desilver, D. (2016). In the U. S. and abroad, more young adults are living with their parents. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/05/24/in-the-u-s-and-abroad-more-young-adults-are-living-with-their-parents/

Dye, J. L. (2010). Fertility of American women: 2008. Current Population Reports. Retrieved from www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p20-563.pdf.

Eastley, R., & Wilcock, G. K. (1997). Prevalence and correlates of aggressive behaviors occurring in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 12, 484-487.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Guthrie, I.K., Murphy, B.C., & Reiser, M. (1999). Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Development, 70, 513-534.

Eisenberg, N., Hofer, C., Spinrad, T., Gershoff, E., Valiente, C., Losoya, S. L., Zhou, Q., Cumberland, A., Liew, J., Reiser, M., & Maxon, E. (2008). Understanding parent-adolescent conflict discussions: Concurrent and across-time prediction from youths’ dispositions and parenting. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 73, (Serial No. 290, No. 2), 1-160.

Emslie, C., Hunt, K., & Lyons, A. (2013. The role of alcohol in forging and maintaining friendships amongst Scottish men in midlife. Health Psychology, 32(10, 33-41.

Erikson, E. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. (1959). Identity and the life cycle. New York: Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. (1982). The life cycle completed. New York: Norton & Company.

Fehr, B. (2008). Friendship formation. In S. Sprecher, A. Wenzel, & J. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of Relationship Initiation (pp. 29–54). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Gibbons, C., Creese, J., Tran, M., Brazil, K., Chambers, L., Weaver, B., & Bedard, M. (2014). The psychological and health consequences of caring for a spouse with dementia: A critical comparison of husbands and wives. Journal of Women & Aging, 26, 3-21.

Goldscheider, F., & Kaufman, G. (2006). Willingness to stepparent: Attitudes about partners who already have children. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 1415 – 1436.

Goldscheider, F., & Sassler, S. (2006). Creating stepfamilies: Integrating children into the study of union formation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 275 – 291.

Gonzales, N. A., Coxe, S., Roosa, M. W., White, R. M. B., Knight, G. P., Zeiders, K. H., & Saenz, D. (2011). Economic hardship, neighborhood context, and parenting: Prospective effects on Mexican-American adolescent’s mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 98–113.

Gorchoff, S. M., John, O. P., & Helson, R. (2008). Contextualizing change in marital satisfaction during middle age. Psychological Science, 19, 1194–1200.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (2000). The timing of divorce: Predicting when a couple will divorce over a 14-year period. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 62, 737-745.

Greene, S. M., Anderson, E. R., Hetherington, E., Forgtch, M. S., & DeGarmo, D. S. (2003). Risk and resilience after divorce. In F. Walsh (Ed.), Normal family processes: Growing diversity and complexity (3rd ed., pp. 96-120). New York: Guilford Press.

Greenfield, E. A., & Marks, N. F. (2006). Linked lives: Adult children’s problems and their parents’ psychological and relational well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 442-454.

Grusec, J. E., Goodnow, J. J., & Cohen, L. (1996). Household work and the development of concern for others. Developmental Psychology, 32, 999–1007.

Gurrentz, B. (2018). For young adults, cohabitation is up, and marriage is down. US. Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/11/cohabitaiton-is-up-marriage-is-down-for-young-adults.html.

Ha, J., Hong, J., Seltzer, M. M., & Greenberg, J. S. (2008). Age and gender differences in the well-being of midlife and aging parents with children with mental health or developmental problems: Report of a national study. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 49, 301-316.

Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., & Ventura, S. J. (2011). Births: Preliminary data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports, 60(2). Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Hawkley, L. C., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Masi, C. M., Thisted, R. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago health, aging, and marital status transitions and health outcomes social relations study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63, 375–384.

Hayslip Jr., B., Henderson, C. E., & Shore, R. J. (2003). The Structure of Grandparental Role Meaning. Journal of Adult Development, 10(1), 1-13.

Hetherington, E. M. & Kelly, J. (2002). For better or worse: Divorce reconsidered. New York, NY: Norton.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316.

Hyde, J. S., Else-Quest, N. M., & Goldsmith, H. H. (2004). Children’s temperament and behavior problems predict their employed mothers’ work functioning. Child Development, 75, 580–594.

Institute of Medicine. (2015). Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kang, S. W., & Marks, N. F. (2014). Parental caregiving for a child with special needs, marital strain, and physical health: Evidence from National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. 2005. Contemporary Perspectives in Family Research, 8A, 183-209.

Kerr, D. C. R., Capaldi, D. M., Pears, K. C., & Owen, L. D. (2009). A prospective three generational study of fathers’ constructive parenting: Influences from family of origin, adolescent adjustment, and offspring temperament. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1257–1275.

Kiff, C. J., Lengua, L. J., & Zalewski, M. (2011). Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 251–301.

Krause, N. A., Herzog, R., & Baker, E. (1992). Providing support to others and well-being in later life. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 47, P300-311.

Lachman, M. E. (2004). Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 305-331.

Landsford, J. E., Antonucci, T.C., Akiyama, H., & Takahashi, K. (2005). A quantitative and qualitative approach to social relationships and well-being in the United States and Japan. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 36, 1-22.

Lesthaeghe, R. J., & Surkyn, J. (1988). Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Development Review 14(1), 1–45.

Livingston, G. (2014). Four in ten couples are saying I do again. In Chapter 3. The differing demographic profiles of first-time marries, remarried and divorced adults. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/11/14/chapter-3-the-differing-demographic-profiles-of-first-time-married-remarried-and-divorced-adults/

Lucas, R. E. & Donnellan, A. B. (2011). Personality development across the life span: Longitudinal analyses with a national sample from Germany. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 847–861

Martinez, G., Daniels, K., & Chandra, A. (2012). Fertility of men and women aged 15-44 years in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth, 2006-2010. National Health Statistics Reports, 51(April). Hyattsville, MD: U.S., Department of Health and Human Services.

Metlife. (2011). Metlife study of caregiving costs to working caregivers: Double jeopardy for baby boomers caring for their parents. Retrieved from http://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/mmi-caregiving-costs-working-caregivers.pdf

Mitchell, B. A., & Lovegreen, L. D. (2009). The empty nest syndrome in midlife families: A multimethod exploration of parental gender differences and cultural dynamics. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 1651–1670.

Montenegro, X. P. (2003). Lifestyles, dating, and romance: A study of midlife singles. Washington, DC: AARP.

National Alliance for Caregiving. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. 2015. Retrieved from http://www.caregiving.org/caregiving2015.

Neugarten, B. L., & Weinstein, K. K. (1964). The changing American grandparent. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 26, 199–204.

Newton, T., Buckley, A., Zurlage, M., Mitchell, C., Shaw, A., & Woodruff-Borden, J. (2008). Lack of a close confidant: Prevalence and correlates in a medically underserved primary care sample. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 13, 185–192.

Parker, K. & Patten, E. (2013). The sandwich generation: Rising financial burdens for middle-aged Americans. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/01/30/the-sandwich-generation/

Payne, K. K. (2015). The remarriage rate: Geographic variation, 2013. National Center for Family & Marriage Research. Retrieved from http://bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/payne-remarriage-rate-fp-15-08.html

Pew Research Center. (2010). The return of the multi-generational family household. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/03/18/the-return-of-the-multi-generational-family-household/

Pew Research Center. (2010a). How the great recession has changed life in America. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/06/30/how-the-great-recession-has-changed-life-in-america/

Pew Research Center. (2010b). Section 5: Generations and the great recession. Retrieved from http://www.people-press.org/2011/11/03/section-5-generations-and-the-great-recession/

Pew Research Center. (2015). Caring for aging parents. Family support in graying societies. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/05/21/4-caring-for-aging-parents/

Pew Research Center. (2019). Same-sex marriage around the world. Retrieved from https://www.pewforum.org/fact-sheet/gay-marriage-around-the-world/

Prinzie, P., Stams, G. J., Dekovic, M., Reijntjes, A. H., & Belsky, J. (2009). The relations between parents’ Big Five personality factors and parenting: A meta-review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 351–362.

Proulx, C. M., Helms, H. M., & Buehler, C. (2007). Marital Quality and Personal Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(3), 576–593

Saginak, K. A., & Saginak, M. A. (2005). Balancing work and family: Equity, gender, and marital satisfaction. Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 13, 162-166.

Sandberg-Thoma, S. E., Synder, A. R., & Jang, B. J. (2015). Exiting and returning to the parental home for boomerang kids. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 806-818.

Schulz, R., Newsom, J., Mittelmark, M., Burton, L., Hirsch, C., & Jackson, S. (1997). Health effects of caregiving: The caregiver health effects study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 19, 110-116.

Seccombe, K., & Warner, R. L. (2004). Marriages and families: Relationships in social context. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Seltzer, M. M., Floyd, F., Song, J., Greenberg, J., & Hong, J. (2011). Midlife and aging parents of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Impacts of lifelong parenting. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 116, 479-499.

Stewart, S. D., Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2003). Union formation among men in the US: Does having prior children matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 90 – 104.

Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Way, N., Hughes, D., Yoshikawa, H., Kalman, R. K., & Niwa, E. Y. (2008). Parents’ goals for children: The dynamic coexistence of individualism and collectivism in cultures and individuals. Social Development, 17, 183–209.

Teachman, J. (2008). Complex life course patterns and the risk of divorce in second marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 294 – 305.

Thornton, A. (2005). Reading history sideways: The fallacy and enduring impact of the developmental paradigm on family life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Torti, F. M., Gwyther, L. P., Reed, S. D., Friedman, J. Y., & Schulman, K. A. (2004). A multinational review of recent trends and reports in dementia caregiver burden. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 18(2), 99-109.

Umberson, D., Williams, K., Powers, D., Chen, M., & Campbell, A. (2005). As good as it gets? A life course perspective on marital quality. Social Forces, 81, 493-511.

Wang, W., & Parker, K. (2014). Record share of Americans have never married: As values, economics and gender patterns change. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2014/09/2014-09-24_Never-Married-Americans.pdf

Wang, W., & Taylor, P. (2011). For Millennials, parenthood trumps marriage. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Williams, L., Kabamalan, M., & Ogena, N. (2007). Cohabitation in the Philippines: Attitudes and behaviors among young women and men. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(5), 1244–1256.

Witt, J. (2009). SOC. New York: McGraw Hill.

Wu, Z., Sun, L., Sun, Y., Zhang, X., Tao, F., & Cui, G. (2010). Correlation between loneliness and social relationship among empty nest elderly in Anhui rural area, China. Aging and Mental Health, 14, 108–112.

Yeager, C. A., Hyer, L. A., Hobbs, B., & Coyne, A. C., (2010). Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia: The complex relationship between diagnosis and caregiver burden. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31(6), 376-384.

Yu, J., & Xie, Y. (2015). Cohabitation in China: Trends and determinants. Population & Development Review, 41 (4), 607-628.

Zuidema, S. U., de Jonghe, J. F., Verhey, F. R., & Koopman, R. T. (2009). Predictors of neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing home patients: Influence of gender and dementia severity. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(10), 1079-1086.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

OER Attributions

- "Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition" by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0/modified (new introduction text) by Dan Grimes, Portland State University

- Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- Love, Friendship, and Social Support by Debi Brannan and Cynthia D. Mohr is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- "Love and Relationships" by Ellen Skinner & Heather Brule, Portland State University is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Media Attributions

- brothers-444924_640 © Siggy Nowak

- sandwichgen © Pew Research Center

- finanacialstrain © Pew Research Center

- FT_17.05.03_livingAtHome_byGen2 © Pew Research Center

- FT_16.05.20_livingWithParents_Europe © Pew Research Center

- o-OLD-WOMEN-BEST-FRIENDS-facebook