5.5 The Newborn

Learning Objectives

- Describe two common procedures to assess the condition of the newborn.

- Describe problems newborns experience before, during, and after birth.

- Explain the merits of breastfeeding

- Discuss the importance of nutrition to early physical growth, including nutritional concerns for infants and toddlers such as marasmus and kwashiorkor

Assessing the Neonate

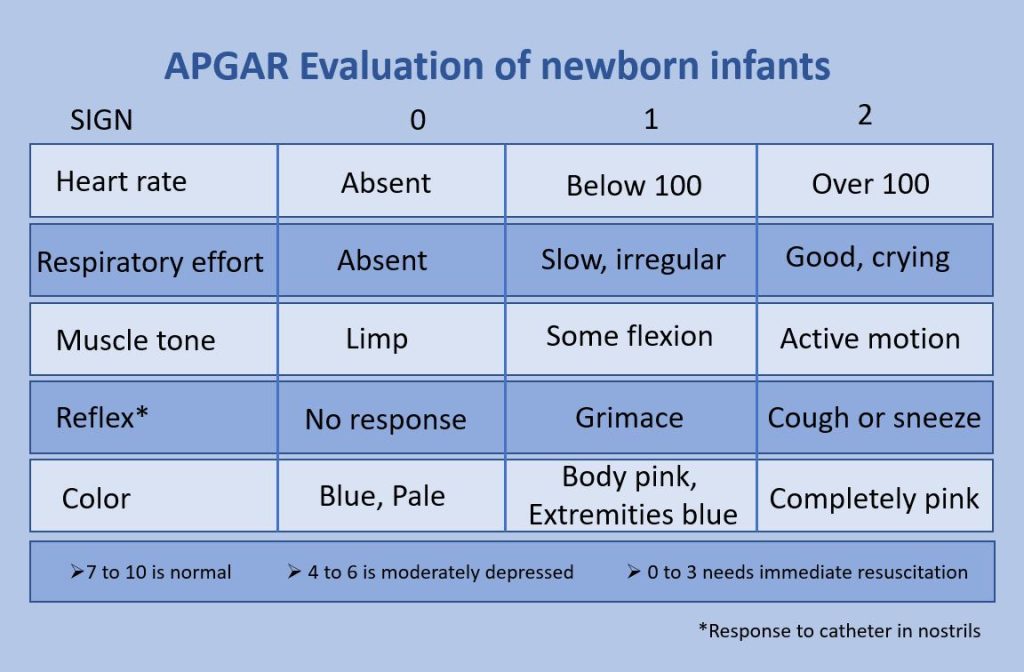

The Apgar assessment is conducted at one minute and five minutes after birth. This is a very quick way to assess the newborn's overall condition. Five measures are assessed: Heart rate, respiration, muscle tone (assessed by touching the baby's palm), reflex response (the Babinski reflex is tested), and color. A score of 0 to 2 is given on each feature examined. An Apgar of 5 or less is cause for concern. The second Apgar should indicate improvement with a higher score (see Figure 5.18).

Another way to assess the condition of the newborn is the Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS). The baby's motor development, muscle tone, and stress response are assessed. This tool has been used around the world to further assess newborn, especially those with low Apgar scores, and to make comparisons of infants in different cultures (Brazelton & Nugent, 1995).

Watch It

Watch this video that explains how to calculate the Apgar score for a newborn.

You can view the transcript for “APGAR Score – MEDZCOOL” here (opens in new window).

Problems of the Newborn

Anoxia

Anoxia is a temporary lack of oxygen to the brain. Difficulty during delivery may lead to anoxia which can result in brain damage or in severe cases, death. Babies who suffer both low birth weight and anoxia are more likely to suffer learning disabilities later in life as well.

Low birth weight

We previously discussed a number of teratogens associated with low birth weight such as alcohol, tobacco, and so on. A child is considered low birth weight if he or she weighs less than 5 pounds 8 ounces (2500 grams). About 8.2 percent of babies born in the United States are of low birth weight (Center for Disease Control, 2015a). A low birth weight baby has difficulty maintaining adequate body temperature because it lacks the fat that would otherwise provide insulation. Such babies are also at more risk for infection, and 67 percent of these babies are also preterm which can increase their risk for respiratory infection. Very low birth weight babies (2 pounds or less) have an increased risk of developing cerebral palsy.

Additionally, Pettersson et al. (2019) analyzed fetal growth and found that reduced birth weight was correlated with a small, but significant increase in several psychiatric disorders in adulthood. These include attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Pettersson et al. theorized that “reduced fetal growth compromises brain development during a critical period, which in turn slightly increases the risk not only for neurodevelopmental disorders but also for virtually all mental health conditions” (p. 540). An insufficient supply of oxygen and nutrients for the developing fetus are proposed as factors that increased the risk for neurodevelopmental disorders.

Preterm

A newborn might also have a low birth weight if it is born at less than 37 weeks gestation, which qualifies it as a preterm baby (CDC, 2015b). Early birth can be triggered by anything that disrupts the mother's system. For instance, vaginal infections can lead to premature birth because such infection causes the mother to release anti-inflammatory chemicals which, in turn, can trigger contractions. Smoking and the use of other teratogens can lead to preterm birth. The earlier a woman quits smoking, the lower the chance that the baby will be born preterm (Someji & Beltrán-Sánchez, 2019). A significant consequence of preterm birth includes respiratory distress syndrome, which is characterized by weak and irregular breathing (United States National Library of Medicine, 2015b).

Saybie (name given to her by the hospital), a baby girl born in San Diego, California is now considered the world’s smallest baby ever to survive (Chiu, 2019). She was born in December 2018 at 23 weeks and 3 days weighing only 8.6 ounces (same size as an apple). After five months in the hospital, Saybie went home in May 2019 weighing 5 pounds.

Small-for-date infants

Infants that have birth weights that are below expectation based on their gestational age are referred to as small-for-date. These infants may be full term or preterm, but still weigh less than 90% of all babies of the same gestational age. This is a very serious situation for newborns as their growth was adversely affected. Regev et al. (2003) found that small-for-date infants died at rates more than four times higher than other infants. Remember that many causes of low birth weight and preterm births are preventable with proper prenatal care.

Newborn Reflexes

Newborns are equipped with a number of reflexes which are involuntary movements in response to stimulation (see Table 5.3). Some of the more common reflexes, such as the sucking reflex and rooting reflex, are important to feeding. The grasping and stepping reflexes are eventually replaced by more voluntary behaviors. Within the first few months of life these reflexes disappear, while other reflexes, such as the eye-blink, swallowing, sneezing, gagging, and withdrawal reflex stay with us as they continue to serve important functions. Reflexes offer pediatricians insight into the maturation and health of the nervous system. In preterm infants and those with neurological impairments, some of these reflexes may be absent at birth. Once present, they may persist longer than in a neurologically healthy infant (El-Dib et al., 2012). Reflexes that persist longer than they should can impede normal development (Berne, 2006).

Table 5.3 Some Common Infant Reflexes

| Reflex | Description | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Sucking | Suck on anything that touches the lips |  |

| Rooting | Turning the head when the cheek is touched |  |

| Grasp | Fingers automatically grip anything the touches the palm of the hand |  |

| Babinski | The toes will fan out and curl when the sole of the foot is stroked from heel to toe |  |

| Moro | A sudden noise or loss of support to the head will cause infants to spread out their arms and legs then quickly contract the limbs inward |  |

| Tonic Neck | When lying on the back with the head to one side infants will extend the arm and leg on that side while flexing the limbs on the opposite side (looks like a fencer pose) |  |

| Stepping | Legs move in stepping like motion when feet touch a smooth surface |  |

adapted from Lally & Valentine-French, 2019

Watch It

Watch this video to see examples of newborn reflexes.

You can view the transcript for “Reflexes in newborn babies” here (opens in new window).

Try It

Infant Growth and Nutrition

Good nutrition in a supportive environment is vital for an infant's healthy growth and development. Remember, from birth to 1 year, infants triple their weight and increase their height by half, and this growth requires good nutrition. For the first 6 months, babies are fed breast milk or formula. Starting good nutrition practices early can help children develop healthy dietary patterns. Infants need to receive nutrients to fuel their rapid physical growth. Malnutrition during infancy can result in not only physical but also cognitive and social consequences. Without proper nutrition, infants cannot reach their physical potential.

Benefits of Breastfeeding

Breast milk is considered the ideal diet for newborns due to the nutritional makeup of colostrum and subsequent breastmilk production. Colostrum, the milk produced during pregnancy and just after birth, has been described as “liquid gold.” Colostrum is packed with nutrients and other important substances that help the infant build up their immune system. Most babies will get all the nutrition they need through colostrum during the first few days of life (CDC, 2018).[1] Breast milk changes by the third to fifth day after birth, becoming much thinner, but containing just the right amount of fat, sugar, water, and proteins to support overall physical and neurological development. It provides a source of iron more easily absorbed in the body than the iron found in dietary supplements, it provides resistance against many diseases, it is more easily digested by infants than formula, and it helps babies make a transition to solid foods more easily than if bottle-fed.

The reason infants need such a high fat content is the process of myelination which requires fat to insulate the neurons. There has been some research, including meta-analyses, to show that breastfeeding is connected to advantages with cognitive development (Anderson et al. 1999)[2]. Low birth weight infants had greater benefits from breastfeeding than did normal-weight infants in a meta-analysis of twenty controlled studies examining the overall impact of breastfeeding (Anderson et al., 1999). This meta-analysis showed that breastfeeding may provide nutrients required for rapid development of the immature brain and be connected to more rapid or better development of neurologic function. The studies also showed that a longer duration of breastfeeding was accompanied by greater differences in cognitive development between breastfed and formula-fed children. Whereas normal-weight infants showed a 2.66-point difference, low-birth-weight infants showed a 5.18-point difference in IQ compared with weight-matched, formula-fed infants (Anderson et al, 1999). These studies suggest that nutrients present in breast milk may have a significant effect on neurologic development in both premature and full-term infants.

For most babies, breast milk is also easier to digest than formula. Formula-fed infants experience more diarrhea and upset stomachs. The absence of antibodies in formula often results in a higher rate of ear infections and respiratory infections. Children who are breastfed have lower rates of childhood leukemia, asthma, obesity, type 1 and 2 diabetes, and a lower risk of SIDS. For all of these reasons, it is recommended that mothers breastfeed their infants until at least 6 months of age and that breast milk be used in the diet throughout the first year (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004a in Berk, 2007).

Several recent studies have reported that it is not just babies that benefit from breastfeeding. Breastfeeding stimulates contractions in the uterus to help it regain its normal size, and women who breastfeed are more likely to space their pregnancies farther apart. Mothers who breastfeed are at lower risk of developing breast cancer, especially among higher-risk racial and ethnic groups (Islami et al., 2015).[3] Other studies suggest that women who breastfeed have lower rates of ovarian cancer (Titus-Ernstoff et al., 2010)[4], and reduced risk for developing Type 2 diabetes (Gunderson, et al., 2015)[5], and rheumatoid arthritis (Karlson et al., 2004).[6]

Links to Learning: A Historic Look at Breastfeeding

The use of wet nurses, or lactating women, hired to nurse others' infants, during the middle ages eventually declined, and mothers increasingly breastfed their own infants in the late 1800s. In the early part of the 20th century, breastfeeding began to go through another decline, and by the 1950s it was practiced less frequently by middle class, more affluent mothers as formula began to be viewed as superior to breast milk. In the late 1960s and 1970s, there was again a greater emphasis placed on natural childbirth and breastfeeding and the benefits of breastfeeding were more widely publicized. Gradually, rates of breastfeeding began to climb, particularly among middle-class educated mothers who received the strongest messages to breastfeed.

Today, new mothers receive consultation from lactation specialists before being discharged from the hospital to ensure that they are informed of the benefits of breastfeeding and given support and encouragement to get their infants accustomed to taking the breast. This does not always happen immediately, and first-time mothers, especially, can become upset or discouraged. In this case, lactation specialists and nursing staff can encourage the mother to keep trying until the baby and mother are comfortable with the feeding.

As of 2022, the recommendation from the American Academy of Pediatrics is that breastfeeding is the only source of nutrition for an infant for the first six months of life and that breastfeeding should be supported for two years or beyond (Meek & Noble, 2022) Most mothers who breastfeed in the United States stop breastfeeding at about 6-8 weeks, often in order to return to work outside the home (United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), 2011[7]). Mothers can certainly continue to provide breast milk to their babies by expressing and freezing the milk to be bottle fed at a later time or by being available to their infants at feeding time, but some mothers find that after the initial encouragement they receive in the hospital to breastfeed, the outside world is less supportive of such efforts. Some workplaces support breastfeeding mothers by providing flexible schedules and welcoming infants, but many do not. And the public support of breastfeeding is sometimes lacking. The Providing Urgent Maternal Protections (PUMP) for Nursing Mothers Act was signed into law in December 2022, requiring employers to provide break time and a private place to express breastmilk and expanding existing protections to an additional nine million employees (U.S. Department of Labor, 2023). It has yet to be determined the extent to which these protections improve breastfeeding rates in the United States. Women in Canada are more likely to breastfeed than are those in the United States, and the Canadian health recommendation is for breastfeeding to continue until 2 years of age. Facilities in public places in Canada such as malls, ferries, and workplaces provide more support and comfort for the breastfeeding mother and child than found in the United States.

In addition to the nutritional and health benefits of breastfeeding, breast milk is free! Anyone who has priced formula recently can appreciate this added incentive to breastfeeding. Prices for a month’s worth of formula can easily range from $130-$200. Prices for a year’s worth of formula and feeding supplies can cost well over $1,500 (USDHHS, 2011). One reason for high formula costs is a low supply of the product combined with high consumer demand. Supply chain issues decreased the availability of infant formula leading to a severe, acute shortage in May 2022 (Abrams & Duggan, 2022) that subsequently increased the frequency of unsafe infant feeding practices among parents desperate to feed their infants (Cernioglo & Smilowitz, 2023).

Links to Learning

- To learn more about breastfeeding, visit this resource from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources: Your Guide to Breastfeeding.

- Visit Kids Health on Breastfeeding vs. Formula Feeding to learn more about the benefits and challenges of breastfeeding and formula-feeding. Click on the speaker icon to listen to the narration of the article if you would like.

- Watch this video from the Psych SciShow "Bad Science: Breastmilk and Formula" to learn about research related to both breastfeeding and formula-feeding. This will open the door for further discussion about formula-feeding as we move to the next section below.

When Breastfeeding Doesn't Work

There are occasions where mothers may be unable to breastfeed babies, often for a variety of health, social, and emotional reasons. For example, breastfeeding generally does not work:

- when the baby is adopted or born via surrogate who is unavailable to breastfeed

- when the biological mother has a transmissible disease such as tuberculosis or HIV

- when the mother is addicted to drugs or taking any medication that may be harmful to the baby (including some types of birth control)

- when the infant was born to (or adopted by) a family with two fathers and the surrogate mother is not available to breastfeed

- when there are attachment issues between mother and baby

- when the mother or the baby is in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) after the delivery process

- when the baby and mother are attached but the mother does not produce enough breast-milk

One early argument given to promote the practice of breastfeeding (when health issues are not the case) is that it promotes bonding and healthy emotional development for infants. However, this does not seem to be a unique case. Breastfed and bottle-fed infants adjust equally well emotionally (Ferguson & Woodward, 1999). This is good news for mothers who may be unable to breastfeed for a variety of reasons and for fathers who might feel left out as a result.

Try It

Introducing Solid Foods

Breast milk or formula is the only food a newborn needs, and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months after birth. Solid foods can be introduced from around six months onward when babies develop stable sitting and oral feeding skills but should be used only as a supplement to breast milk or formula. By six months, the gastrointestinal tract has matured, solids can be digested more easily, and allergic responses are less likely. The infant is also likely to develop teeth around this time, which aids in chewing solid food. Iron-fortified infant cereal, made of rice, barley, or oatmeal, is typically the first solid introduced due to its high iron content. Cereals can be made of rice, barley, or oatmeal. Generally, salt, sugar, processed meat, juices, and canned foods should be avoided.

Though infants usually start eating solid foods between 4 and 6 months of age, more and more solid foods are consumed by a growing toddler. Pediatricians recommended introducing foods one at a time, and for a few days, in order to identify any potential food allergies. Toddlers may be picky at times, but it remains important to introduce a variety of foods and offer food with essential vitamins and nutrients, including iron, calcium, and vitamin D.

Global Considerations and Malnutrition

In the 1960s, formula companies led campaigns in developing countries to encourage mothers to feed their babies on infant formula. Many mothers felt that formula would be superior to breast milk and began using formula. The use of formula can certainly be healthy under conditions in which there is adequate, clean water with which to mix the formula and adequate means to sanitize bottles and nipples. However, in many of these countries, such conditions were not available and babies often were given diluted, contaminated formula which made them become sick with diarrhea and become dehydrated. These conditions continue today and now many hospitals prohibit the distribution of formula samples to new mothers in efforts to get them to rely on breastfeeding. Many of these mothers do not understand the benefits of breastfeeding and have to be encouraged and supported in order to promote this practice.

The World Health Organization (2018) recommends:

- initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth

- exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life

- introduction of solid foods at six months together with continued breastfeeding up to two years of age or beyond

Links to Learning

Breastfeeding could save the lives of millions of infants each year, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), yet fewer than 40 percent of infants are breastfed exclusively for the first 6 months of life. Most women can breastfeed unless they are receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy, have HIV, are dependent on illicit drugs, or have active untreated tuberculosis. Because of the great benefits of breastfeeding, WHO, UNICEF and other national organizations are working together with the government to step up support for breastfeeding globally.

Find out more statistics and recommendations for breastfeeding at the WHO's 10 facts on breastfeeding. You can also learn more about efforts to promote breastfeeding in Peru: "Protecting Breastfeeding in Peru".

Children in developing countries and countries experiencing the harsh conditions of war are at risk for two major types of malnutrition. Infantile marasmus refers to starvation due to a lack of calories and protein. Children who do not receive adequate nutrition lose fat and muscle until their bodies can no longer function. Babies who are breastfed are much less at risk of malnutrition than those who are bottle-fed. After weaning, children who have diets deficient in protein may experience kwashiorkor, or the “disease of the displaced child,” often occurring after another child has been born and taken over breastfeeding. This results in a loss of appetite and swelling of the abdomen as the body begins to break down the vital organs as a source of protein.

Watch It

Watch this video to learn more about the signs and symptoms of kwashiorkor and marasmus.

Try It

Conclusions

As you can see, what may seem like a simple process is in fact a beautiful and delicate journey. Each pregnancy and birth story is unique and comes with surprises and sometimes challenges. As medical technology has rapidly improved, parents are empowered with more information and more choices when it comes to their pregnancy and birth. However, just because interventions are available does not mean that this is the path for all birthing people. As we learned in the case of Serena Williams and Allyson Felix, even in the U.S. sometimes medical care can go awry, and this risk is critically high among Black women. Each birthing person needs to be an active advocate for themself and their baby during pregnancy and delivery, and the healthcare system needs to address the crisis in maternal mortality among Black women.

References (Click to expand)

Abrams, S. A., & Duggan, C. P. (2022). Infant and child formula shortages: now is the time to prevent recurrences. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 116(2), 289-292.

Anderson, J.W., Johnstone, B.M., & Remley, D.T. (1999). Breast-feeding and cognitive development: a meta-analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70(4), 525–535, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/70.4.525

Berne, S. A. (2006). The primitive reflexes: Considerations in the infant. Optometry & Vision Development, 37(3), 139-145.

Brazelton, T. B., & Nugent, J. K. (1995). Neonatal behavioral assessment scale. London: Mac Keith Press.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015a). Birthweight and gestation. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/birthweight.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015b). Preterm birth. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pretermbirth.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). What to Expect While Breastfeeding. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/InfantandToddlerNutrition/breastfeeding/what-to-expect.html

Cernioglo, K., & Smilowitz, J. T. (2023). Infant feeding practices and parental perceptions during the 2022 United States infant formula shortage crisis. BMC pediatrics, 23(1), 320.

Chiu, A. (2019, May 30). ‘She’s a miracle’: Born weighing about as much as ‘a large apple,’ Saybie is the world’s smallest surviving baby. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2019/05/30/world-smallest-surviving-baby-saybie-miracle/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.7c8d0bb6acf7

El-Dib, M., Massaro, A. N., Glass, P., & Aly, H. (2012). Neurobehavioral assessment as a predictor of neurodevelopmental outcome in preterm infants. Journal of Perinatology, 32(4), 299-303.

Fergusson, D. M., & Woodward, L. J. (1999). Maternal age and educational and psychosocial outcomes in early adulthood. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 40, 479-489.

Gunderson, E.P., Hurston, S.R., Dewey, K.G., Faith, M.S., Charvat-Aguilar, N., Khoury, V. C., Nguyen, V.T., & Quesenberry, C.P. (2015). The study of women, infant feeding and type 2 diabetes after GDM pregnancy and growth of their offspring (SWIFT Offspring study): prospective design, methodology and baseline characteristics. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15, 150 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0587-z

Islami, F., Liu, Y., Jemal, A., Zhou, J., Weiderpass, E., Colditz, G., Boffetta, P., & Weiss, M. (2015). Breastfeeding and breast cancer risks by receptor status- a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology, 26(12), 2398–2407

Karlson, E.W., Mandl, L.A., Hankinson, S. E., & Grodstein, F. (2004). Do breast-feeding and other reproductive factors influence future risk of rheumatoid arthritis? Results from the Nurses' Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 50,11, 3458-67.

Meek, J. Y., Noble, L., & Section on Breastfeeding. (2022). Policy statement: breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 150(1), e2022057988.

Pettersson, E., Larsson, H., D’Onofrio, B., Almqvist, C., & Lichtenstein, P. (2019). Association of fetal growth with general and specific mental health conditions. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(5), 536-543. Doi:10.1001jamapsychiatry.2018.4342.

Regev, R.H., Lusky, T. Dolfin, I. Litmanovitz, S. Arnon, B. & Reichman. (2003). Excess mortality and morbidity among small-for-gestational-age premature infants: A population based study. Journal of Pediatrics, 143, 186-191.

Someji, S., & Beltrán-Sánchez, H. (2019). Association of maternal cigarette smoking and smoking cessation with preterm birth. JAMA Network Open, 2(4), e192514. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2514

United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Women’s Health (2011). Your guide to breast feeding. Washington D.C.

United States Department of Labor. (2022). FLSA Protections to Pump at Work. Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/pump-at-work

United States National Library of Medicine. (2015b). Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001563.htm

Titus-Ernstoff, Rees, L. Terry, R.R., & Cramer, D. W. (2010). Breast-feeding the last born child and risk of ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes Control, 21(2), 201–207.

World Health Organization. (2018). Breastfeeding. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_2

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

- "Beginnings: Conception and Prenatal Development" by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

- "Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition" by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0

- "Newborn Assessment and Risks." Authored by: Julie Lazzara for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/chapter/newborn-assessment-and-risks/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology. Authored by: Laura Overstreet. Located at: http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Infant Nutrition. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infant_nutrition. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Nutrition. Authored by: Tera Jones for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/chapter/nutrition/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Toddler Nutrition. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toddler_nutrition. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Putting It Together: Prenatal Developmen. Authored by: Julie Lazzara for Lumen Learning. Located at: http://Lumen%20Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

Media Attributions

- APGAR_score © Dr.Vijaya chandar is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Human_Infant_in_Incubator © Zerbey at the English language Wikipedia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- saybie3jpeg

- Girl eating rice. Authored by: tigerpuppala_2. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infant_nutrition#/media/File:First_rice.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- From Colostrum to Breastmilk. # Days after birth. Authored by: Amada44. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:From_Colostrum_to_Breastmilk_-_4241.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mother. Authored by: Pexels. Located at: https://pixabay.com/images/id-1284353/. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

All Rights Reserved Content

- APGAR Score - MEDZCOOL. Authored by: Medzcool. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=98ikG8a9JKs. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Child Malnutrition - What? How? And when to Refer. Provided by: iheed. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bqEIcMMmj5M. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Reflexes in newborn babies. Authored by: Bernadette Bos. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sv5SsLH70mY. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- What to Expect While Breastfeeding. CDC. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/InfantandToddlerNutrition/breastfeeding/what-to-expect.html. ↵

- Anderson, J.W., Johnstone, B.M., & Remley, D.T. (1999). Breast-feeding and cognitive development: a meta-analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70, 4, 525–535, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/70.4.525 ↵

- Islami, F., Liu, Y., Jemal, A., Zhou, J., Weiderpass, E., Colditz, G., Boffetta, P., & Weiss, M. (2015). Breastfeeding and breast cancer risks by receptor status- a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology, 26,12. 2398–2407. ↵

- Titus-Ernstoff, Rees, L. Terry, R.R., & Cramer, D. W. (2010). Breast-feeding the last born child and risk of ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 21(2), 201–207. ↵

- Gunderson, E.P., Hurston, S.R., Dewey, K.G., Faith, M.S., Charvat-Aguilar, N., Khoury, V. C., Nguyen, V.T., & Quesenberry, C.P. (2015). The study of women, infant feeding and type 2 diabetes after GDM pregnancy and growth of their offspring (SWIFT Offspring study): prospective design, methodology and baseline characteristics. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15,150 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0587-z ↵

- Karlson, E.W., Mandl, L.A., Hankinson, S. E., & Grodstein, F. (2004). Do breast-feeding and other reproductive factors influence future risk of rheumatoid arthritis? Results from the Nurses' Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 50,11, 3458-67. ↵

- United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Women’s Health (2011). Your guide to breast feeding. Washington D.C. ↵