6.3 Endocrine System Changes

Learning Objectives

- Identify physical transformations in adolescence related to sexual maturation.

- Describe the effects associated with early and late onset of puberty, and how they differ for boys and girls.

- Explain the climateric, it’s impact on life and sexuality in midlife, and differing impacts of aging on women and men.

Puberty and Adolescence

Puberty is a period of rapid growth and sexual maturation. These changes begin sometime between age eight and fourteen. Girls begin puberty at around ten years of age and boys begin approximately two years later. Pubertal changes take around three to four years to complete.

One of the hallmark features of puberty is the development of sexual maturity. Sexual changes are divided into two categories: Primary sexual characteristics and secondary sexual characteristics. Primary sexual characteristics are changes in the reproductive organs. For females, primary characteristics include growth of the uterus and menarche or the first menstrual period. The female gametes, which are stored in the ovaries, are present at birth, but are immature. Each ovary contains about 400,000 gametes, but only 500 will become mature eggs (Crooks & Baur, 2007). Beginning at puberty, one ovum ripens and is released about every 28 days during the menstrual cycle. Stress and higher percentage of body fat can bring menstruation at younger ages. For males, this includes growth of the testes, penis, scrotum, and spermarche or first ejaculation of semen. This occurs between 11 and 15 years of age.

Secondary sexual characteristics are visible physical changes that signal sexual maturity but are not directly linked to reproduction. For females, breast development occurs around age 10, although full development takes several years. Hips broaden, and pubic and underarm hair develops and also becomes darker and coarser. For males this includes broader shoulders and a lower voice as the larynx grows. Hair becomes coarser and darker, and hair growth occurs in the pubic area, under the arms and on the face.

Effects of Pubertal Age

The age of puberty is getting younger for children throughout the world, referred to as the secular trend. According to Euling et al. (2008) data are sufficient to suggest a trend toward an earlier breast development onset and menarche in girls. A century ago the average age of a girl’s first period in the United States and Europe was 16, while today it is around 13. Because there is no clear marker of puberty for boys, it is harder to determine if boys are also maturing earlier. In addition to better nutrition, less positive reasons associated with early puberty for girls include increased stress, obesity, and endocrine disrupting chemicals.

Cultural differences are noted with African American girls enter puberty the earliest. Hispanic girls start puberty the second earliest, while European-American girls rank third in their age of starting puberty, and Asian-American girls, on average, develop last. Although African-American girls are typically the first to develop, they are less likely to experience negative consequences of early puberty when compared to European-American girls (Weir, 2016).

Watch It

Watch this video to see a summary of the main biological changes that occur during puberty.

Research has demonstrated mental health problems linked to children who begin puberty earlier than their peers. For girls, early puberty is associated with depression, substance use, eating disorders, disruptive behavior disorders, and early sexual behavior (Graber, 2013). Early maturing girls demonstrate more anxiety and less confidence in their relationships with family and friends, and they compare themselves more negatively to their peers (Weir, 2016).

Problems with early puberty seem to be due to the mismatch between the child’s appearance and the way she acts and thinks. Adults especially may assume the child is more capable than she actually is, and parents might grant more freedom than the child’s age would indicate. For girls, the emphasis on physical attractiveness and sexuality is emphasized at puberty and they may lack effective coping strategies to deal with the attention they receive, especially from older boys.

Additionally, mental health problems are more likely to occur when the child is among the first in his or her peer group to develop. Because the preadolescent time is one of not wanting to appear different, early developing children stand out among their peer group and gravitate toward those who are older. For girls, this results in them interacting with older peers who engage in risky behaviors such as substance use and early sexual behavior (Weir, 2016).

Boys also see changes in their emotional functioning at puberty. According to Mendle et al. (2010), while most boys experienced a decrease in depressive symptoms during puberty, boys who began puberty earlier and exhibited a rapid tempo, or a fast rate of change, actually increased in depressive symptoms. The effects of pubertal tempo were stronger than those of pubertal timing, suggesting that rapid pubertal change in boys may be a more important risk factor than the timing of development. In a further study to better analyze the reasons for this change, Mendle et al. (2012) found that both early maturing boys and rapidly maturing boys displayed decrements in the quality of their peer relationships as they moved into early adolescence, whereas boys with more typical timing and tempo development actually experienced improvements in peer relationships. The researchers concluded that the transition in peer relationships may be especially challenging for boys whose pubertal maturation differs significantly from those of others their age. Consequences for boys attaining early puberty were increased odds of cigarette, alcohol, or another drug use (Dudovitz, et al., 2015). However, from the outside, early maturing boys are also often perceived as well-adjusted, popular, and tend to hold leadership positions.

Try It

The Climacteric

One biologically based change that occurs during midlife is the climacteric. During midlife, men may experience a reduction in their ability to reproduce. Women, however, lose their ability to reproduce once they reach menopause.

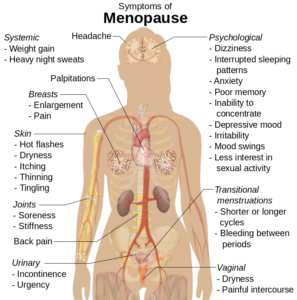

Menopause

Menopause refers to a period of transition in which a woman’s ovaries stop releasing eggs and the level of estrogen and progesterone production decreases. After menopause, a woman’s menstruation ceases (U. S. National Library of Medicine and National Institute of Health [NLM/NIH], 2007).

Changes typically occur between the mid 40s and mid 50s. The median age range for a woman to have her last menstrual period is 50-52, but ages vary. A woman may first begin to notice that her periods are more or less frequent than before. These changes in menstruation may last from 1 to 3 years. After a year without menstruation, a woman is considered post-menopausal and no longer capable of reproduction. (Keep in mind that some women, however, may experience another period even after going for a year without one.) The loss of estrogen also affects vaginal lubrication which diminishes and becomes more watery. The vaginal wall also becomes thinner, and less elastic.

Menopause is not seen as universally distressing (Lachman, 2004). Changes in hormone levels are associated with hot flashes and sweats in some women, but women vary in the extent to which these are experienced. Depression, irritability, and weight gain are not necessarily due to menopause (Avis, 1999; Rossi, 2004). Depression and mood swings are more common during menopause in women who have prior histories of these conditions rather than those who have not. The incidence of depression and mood swings is not greater among menopausal women than non-menopausal women.

Cultural influences seem to also play a role in the way menopause is experienced. For example, once after listing the symptoms of menopause in a psychology course, a woman from Kenya responded, “We do not have this in my country or if we do, it is not a big deal,” to which some U.S. students replied, “I want to go there!” Indeed, there are cultural variations in the experience of menopausal symptoms. Hot flashes are experienced by 75 percent of women in Western cultures, but by less than 20 percent of women in Japan (Obermeyer in Berk, 2007).

Women in the United States respond differently to menopause depending upon the expectations they have for themselves and their lives. White, African-American, Mexican-American, and career-oriented women overall tend to think of menopause as a liberating experience. Nevertheless, there has been a popular tendency to erroneously attribute frustrations and irritations expressed by women of menopausal age to menopause and thereby not take her concerns seriously. Fortunately, many practitioners in the United States today are normalizing rather than pathologizing menopause.

Concerns about the effects of hormone replacement have changed the frequency with which estrogen replacement and hormone replacement therapies have been prescribed for menopausal women. Estrogen replacement therapy was once commonly used to treat menopausal symptoms. But more recently, hormone replacement therapy has been associated with breast cancer, stroke, and the development of blood clots (NLM/NIH, 2007). Most women do not have symptoms severe enough to warrant estrogen or hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Women who do require HRT can be treated with lower doses of estrogen and monitored with more frequent breast and pelvic exams. There are also some other ways to reduce symptoms. These include avoiding caffeine and alcohol, eating soy, remaining sexually active, practicing relaxation techniques, and using water-based lubricants during intercourse.

Fifty million women in the USA aged 50-55 are post-menopausal. During and after menopause a majority of women will experience weight gain. Changes in estrogen levels lead to a redistribution of body fat from hips and back to stomachs. This is more dangerous to general health and wellbeing because abdominal fat is largely visceral, meaning it is contained within the abdominal cavity and may not look like typical weight gain. That is, it accumulates in the space between the liver, intestines and other vital organs. This is far more harmful to health than subcutaneous fat which is the kind of fat located under the skin. It is possible to be relatively thin and retain a high level of visceral fat, yet this type of fat is deemed especially harmful by medical research.

Watch It

This TED Talk discusses the impact of menopause on brains.

Andropause

Do males experience a climacteric? Yes. While they do not lose their ability to reproduce as they age, they do tend to produce lower levels of testosterone and fewer sperm. However, men are capable of reproduction throughout life after puberty. It is natural for sex drive to diminish slightly as men age, but a lack of sex drive may be a result of extremely low levels of testosterone. About 5 million men experience low levels of testosterone that results in symptoms such as a loss of interest in sex, loss of body hair, difficulty achieving or maintaining erection, loss of muscle mass, and breast enlargement. This decrease in libido and lower testosterone (androgen) levels is known as andropause, although this term is somewhat controversial as this experience is not clearly delineated, as menopause is for women. Low testosterone levels may be due to glandular disease such as testicular cancer. Testosterone levels can be tested and if they are low, men can be treated with testosterone replacement therapy. This can increase sex drive, muscle mass, and beard growth. However, long term HRT for men can increase the risk of prostate cancer (The Patient Education Institute, 2005).

The debate around declining testosterone levels in men may hide a fundamental fact. The issue is not about individual males experiencing individual hormonal change at all. We have all seen the adverts on the media promoting substances to boost testosterone: “Is it low-T?” The answer is probably in the affirmative, if somewhat relative. That is, in all likelihood they will have lower testosterone levels than their fathers. However, it is equally likely that the issue does not lie solely in their individual physiological make up, but is rather a generational transformation (Travison et al, 2007). Why this has occurred in such a dramatic fashion is still unknown. There is evidence that low testosterone may have negative health effects on men. In addition, there are studies which show evidence of rapidly decreasing sperm count and grip strength. Exactly why these changes are happening is unknown and will likely involve more than one cause.[1]

The Climacteric and Sexuality

Sexuality is an important part of people’s lives at any age. Midlife adults tend to have sex lives that are very similar to that of younger adulthood. And many women feel freer and less inhibited sexually as they age. However, a woman may notice less vaginal lubrication during arousal and men may experience changes in their erections from time to time. This is particularly true for men after age 65. Men who experience consistent problems are likely to have other medical conditions (such as diabetes or heart disease) that impact sexual functioning (National Institute on Aging, 2005).

Couples continue to enjoy physical intimacy and may engage in more foreplay, oral sex, and other forms of sexual expression rather than focusing as much on sexual intercourse. Risk of pregnancy continues until a woman has been without menstruation for at least 12 months, however, and couples should continue to use contraception. People continue to be at risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections such as genital herpes, chlamydia, and genital warts. About ten percent of new HIV diagnoses in the United States are in people 55 and older.[2] Of all people living with HIV, almost 50% are aged 50 or over. [3] Getting tested is important- even people who are not high-risk can be impacted. Also, practicing safe sex is important at any age- safe sex is not just about avoiding an unwanted pregnancy; it is about protecting yourself from STDs as well. Hopefully, when partners understand how aging affects sexual expression, they will be less likely to misinterpret these changes as a lack of sexual interest or displeasure in the partner and be more able to continue to have satisfying and safe sexual relationships.

Women and Aging

In Western society, aging for women is much more stressful than for men as society emphasizes youthful beauty and attractiveness (Slevin, 2010). The description that aging men are viewed as “distinguished” and aging women are viewed as “old” is referred to as the double standard of aging (Teuscher & Teuscher, 2006). Since women have traditionally been valued for their reproductive capabilities, they may be considered old once they are post-menopausal. In contrast, men have traditionally been valued for their achievements, competence, and power, and therefore are not considered old until decades later when they are physically unable to work (Carroll, 2016). Consequently, women experience more fear, anxiety, and concern about their identity as they age, and may feel pressure to prove themselves as productive and valuable members of society (Bromberger et al., 2013).

Attitudes about aging, however, do vary by race, culture, and sexual orientation. In some cultures, aging women gain greater social status. For example, as Asian women age they attain greater respect and have greater authority in the household (Fung, 2013). Compared to white women, Black and Latina women possess fewer stereotypes about aging (Schuler et al., 2008). Lesbians are also more positive about aging and looking older than heterosexual women (Slevin, 2010). The impact of media certainly plays a role in how women view aging by selling anti-aging products and supporting cosmetic surgeries to look younger (Gilleard & Higgs, 2000).

Try It

References (Click to expand)

Bromberger, J. T., Kravitz, H. M., Chang, Y., Randolph Jr, J. F., Avis, N. E., Gold, E. B., & Matthews, K. A. (2013). Does risk for anxiety increase during the menopausal transition? Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Menopause, 20(5), 488.

Carroll, J. L. (2016). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity. Cengage Learning.

Crooks, K. L., & Baur, K. (2007). Our sexuality (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Dudovitz, R. N., Chung, P. J., Elliott, M. N., Davies, S. L., Tortolero, S., Baumler, E., … & Schuster, M. A. (2015). Peer Reviewed: Relationship of Age for Grade and Pubertal Stage to Early Initiation of Substance Use. Preventing chronic disease, 12.

Euling, S. Y., Herman-Giddens, M.E., Lee, P.A., Selevan, S. G., Juul, A., Sorensen, T. I., Dunkel, L., Himes, J.H., Teilmann, G., & Swan, S.H. (2008). Examination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings. Pediatrics, 121, S172-91. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1813D.

Fung, H. H. (2013). Aging in culture. The Gerontologist, 53(3), 369-377.

Gilleard, C., & Higgs, P. (2000). Cultures of aging: Self, citizen and the body. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Publishers.

Graber, J. A. (2013). Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and Behavior, 64, 262-289.

Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2010). Development’s tortoise and hare: Pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1341–1353.

Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2012). Peer relationships and depressive symptomatology in boys at puberty. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 429–435.

Schuler, P. B., Vinci, D., Isosaari, R. M., Philipp, S. F., Todorovich, J., Roy, J. L., & Evans, R. R. (2008). Body-shape perceptions and body mass index of older African American and European American women. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 23, 255-264.

Slevin, K. F. (2010). “If I had lots of money… I’d have a body makeover:” Managing the Aging Body. Social Forces, 88(3), 1003-1020.

Teuscher, U., & Teuscher, C. (2007). Reconsidering the double standard of aging: Effects of gender and sexual orientation on facial attractiveness ratings. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(4), 631-639.

Weir, K. (2016). The risks of earlier puberty. Monitor on Psychology, 47(3), 41-44.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

CC Licensed Content

- “Physical Development During Adolescence” by Lumen Learning is Licensed under a CC BY: Attribution.

- Stages of Development. Provided by: OpenStax College. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/4abf04bf-93a0-45c3-9cbc-2cefd46e68cc@4.100:1/Psychology. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11629/latest/.

- Adolescence. Provided by: Boundless. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-psychology/chapter/adolescence/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- “Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0/modified and adapted by Ellen Skinner & Dan Grimes, Portland State UniversityLifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License/modified and adapted by Ellen Skinner & Dan Grimes, Portland State University

- “Puberty & Cognition” by Ellen Skinner, Dan Grimes, & Brandy Brennan, Portland State University is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0.

- “Physical Development in Midlife.” Authored by: Ronnie Mather for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/chapter/physical-development-in-midlife/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology. Authored by: Laura Overstreet. Located at: http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/. License: CC BY: Attribution

Media Attributions

- Sexual Maturation images. Provided by: CK-12. Located at: https://www.ck12.org/book/Human-Biology-Your-Changing-Body/section/4.1/. License: CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- Menopause. Authored by: Mikael Hu00e4ggstru00f6m. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Symptoms_of_menopause_(vector).svg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- How menopause affects the brain by TED is licensed CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0

- young-people-563026_640 © Christoph Müller

All Rights Reserved Content

- Physical development in adolescence | Behavior | MCAT. Provided by: Khan Academy. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DWKWjpVsGng. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Travison et al (2007) Testoserone levels ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, May). HIV Surveillance Report, 2020; vol. 33. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-33/index.html. ↵

- National Institutes of Health. (2021, August 23). HIV, AIDS, and older adults. National Institute on Aging. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv-aids/fact-sheets/25/80/hiv-and-older-adults ↵