10.4 Cognition in Adolescence and Adulthood

Learning Objectives

- Describe adolescent egocentrism.

- Describe the limitations of adolescent thinking.

- Describe how differences between cross-sectional, longitudinal, and sequential research designed have contributed to our understanding of the development of intelligence in middle adulthood.

- Define crystallized and fluid intelligence.

- Explain how intelligence changes with age.

Cognition in Adolescence

Adolescence is a time of rapid cognitive development. Biological changes in brain structure and connectivity in the brain interact with increased experience, knowledge, and changing social demands to produce rapid cognitive growth. These changes generally begin at puberty or shortly thereafter, and some skills continue to develop as an adolescent ages. Development of executive functions, or cognitive skills that enable the control and coordination of thoughts and behavior, are generally associated with the prefrontal cortex area of the brain. The thoughts, ideas, and concepts developed at this period of life greatly influence one’s future life and play a major role in character and personality formation.

Improvements in basic thinking abilities generally occur in several areas during adolescence:

- Attention. Improvements are seen in selective attention (the process by which one focuses on one stimulus while tuning out another), as well as divided attention (the ability to pay attention to two or more stimuli at the same time).

- Memory. Improvements are seen in working memory and long-term memory.

- Processing speed. Adolescents think more quickly than children. Processing speed improves sharply between age five and middle adolescence, levels off around age 15, and then remains largely the same between late adolescence and adulthood.

Adolescent Egocentrism

Adolescents' newfound meta-cognitive abilities also have an impact on their social cognition, as it results in increased introspection, self-consciousness, and intellectualization. Adolescents are much better able to understand that people do not have complete control over their mental activity. Being able to introspect may lead to forms of egocentrism, or self-focus, in adolescence. Adolescent egocentrism is a term that David Elkind used to describe the phenomenon of adolescents’ inability to distinguish between their perception of what others think about them and what people actually think in reality. Elkind’s theory on adolescent egocentrism is drawn from Piaget’s theory on cognitive developmental stages, which argues that formal operations enable adolescents to construct imaginary situations and abstract thinking.

Accordingly, adolescents are able to conceptualize their own thoughts and conceive of other people’s thoughts. However, Elkind pointed out that adolescents tend to focus mostly on their own perceptions, especially on their behaviors and appearance, because of the “physiological metamorphosis” they experience during this period. This leads to adolescents’ belief that other people are as attentive to their behaviors and appearance as they are themselves (Elkind, 1967; Schwartz et al.., 2008). According to Elkind, adolescent egocentrism results in two distinct problems in thinking: the imaginary audience and the personal fable. These likely peak at age fifteen, along with self-consciousness in general.

Imaginary audience is a term that Elkind used to describe the phenomenon that an adolescent anticipates the reactions of other people to him/herself in actual or impending social situations. Elkind argued that this kind of anticipation could be explained by the adolescent’s conviction that others are as admiring or as critical of them as they are of themselves. As a result, an audience is created, as the adolescent believes that he or she will be the focus of attention. However, more often than not the audience is imaginary because in actual social situations individuals are not usually the sole focus of public attention. Elkind believed that the construction of imaginary audiences would partially account for a wide variety of typical adolescent behaviors and experiences; and imaginary audiences played a role in the self-consciousness that emerges in early adolescence. However, since the audience is usually the adolescent’s own construction, it is privy to his or her own knowledge of him/herself. According to Elkind, the notion of imaginary audience helps to explain why adolescents usually seek privacy and feel reluctant to reveal themselves–it is a reaction to the feeling that one is always on stage and constantly under the critical scrutiny of others.

Elkind also suggested that adolescents have another complex set of beliefs: They are convinced that their own feelings are unique and they are special and immortal. Personal fable is the term Elkind used to describe this notion, which is the complement of the construction of an imaginary audience. Since an adolescent usually fails to differentiate their own perceptions and those of others, they tend to believe that they are of importance to so many people (the imaginary audiences) that they come to regard their feelings as something special and unique. They may feel that they are the only ones who have experienced strong and diverse emotions, and therefore others could never understand how they feel. This uniqueness in one’s emotional experiences reinforces the adolescent’s belief of invincibility, especially to death.

This adolescent belief in personal uniqueness and invincibility becomes an illusion that they can be above some of the rules, constraints, and laws that apply to other people; even consequences such as death (called the invincibility fable). This belief that one is invincible removes any impulse to control one’s behavior (Lin, 2016). Therefore, some adolescents will engage in risky behaviors, such as drinking and driving or unprotected sex, and feel they will not suffer any negative consequences.

Intuitive and Analytic Thinking

Piaget emphasized the sequence of cognitive developments that unfold in four stages. Others suggest that thinking does not develop in sequence, but instead, that advanced logic in adolescence may be influenced by intuition. Cognitive psychologists often refer to intuitive and analytic thought as the dual-process model; the notion that humans have two distinct networks for processing information (Kuhn, 2013.)

Intuitive thought is automatic, unconscious, and fast, and it is more experiential and emotional. In contrast, analytic thought is deliberate, conscious, and rational (logical). Although these systems interact, they are distinguishable (Kuhn, 2013). Intuitive thought is easier, quicker, and more commonly used in everyday life. The discrepancy between the maturation of the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex, as discussed previously, may make teens more prone to emotional intuitive thinking than adults.

As adolescents develop, they gain in logic/analytic thinking ability but may sometimes regress, with social context, education, and experiences becoming major influences. Simply put, being “smarter” as measured by an intelligence test does not advance or anchor cognition as much as having more experience, in school and in life (Klaczynski & Felmban, 2014).

Risk-taking

Because most injuries sustained by adolescents are related to risky behavior (alcohol consumption and drug use, reckless or distracted driving, and unprotected sex), a great deal of research has been conducted to examine the cognitive and emotional processes underlying adolescent risk-taking. In addressing this issue, it is important to distinguish three facets of these questions: (1) whether adolescents are more likely to engage in risky behaviors (prevalence), (2) whether they make risk-related decisions similarly or differently than adults (cognitive processing perspective), or (3) whether they use the same processes but weigh facets differently and thus arrive at different conclusions. Behavioral decision-making theory proposes that adolescents and adults both weigh the potential rewards and consequences of an action. However, research has shown that adolescents seem to give more weight to rewards, particularly social rewards, than do adults. Adolescents value social warmth and friendship, and their hormones and brains are more attuned to those values than to a consideration of long-term consequences (Crone & Dahl, 2012).

Some have argued that there may be evolutionary benefits to an increased propensity for risk-taking in adolescence. For example, without a willingness to take risks, teenagers would not have the motivation or confidence necessary to leave their family of origin. In addition, from a population perspective, is an advantage to having a group of individuals willing to take more risks and try new methods, counterbalancing the more conservative elements typical of the received knowledge held by older adults.

Try It

Cognitive Development in Early Adulthood

Emerging adulthood brings with it the consolidation of formal operational thought, and the continued integration of the parts of the brain that serve emotion, social processes, and planning and problem solving. As a result, rash decisions and risky behavior decrease rapidly across early adulthood. Increases in epistemic cognition are also seen, as young adults' meta-cognition, or thinking about thinking, continues to grow, especially young adults who continue with their schooling.

Perry’s Scheme

One of the first theories of cognitive development in early adulthood originated with William Perry (1970), who studied undergraduate students at Harvard University. Perry noted that over the course of students’ college years, cognition tended to shift from dualism (absolute, black and white, right and wrong type of thinking) to multiplicity (recognizing that some problems are solvable and some answers are not yet known) to relativism (understanding the importance of the specific context of knowledge—it’s all relative to other factors). Similar to Piaget’s formal operational thinking in adolescence, this change in thinking in early adulthood is affected by educational experiences.

Table 9.2 Stages of Perry's Scheme

| Stage | Summary of Position in Perry's Scheme | Basic Example |

|---|---|---|

| Dualism | ||

| The authorities know | “The tutor knows what is right and wrong” | |

| The true authorities are right, the others are frauds | “My tutor doesn’t know what is right and wrong but others do” | |

| There are some uncertainties and the authorities are working on them to find the truth | “My tutors don’t know, but somebody out there is trying to find out” | |

| Multiplicity | ||

| Everyone has the right to their own opinion | “Different tutors think different things” | |

| The authorities don’t want the right answers. They want us to think in a certain way | “There is an answer that the tutors want and we have to find it” | |

| Everything is relative but not equally valid | “There are no right and wrong answers, it depends on the situation, but some answers might be better than others” | |

| You have to make your own decisions | “What is important is not what the tutor thinks but what I think” | |

| Relativism | ||

| First commitment | “For this particular topic I think that….” | |

| Several commitments | “For these topics I think that….” | |

| Believe own values, respect others, be ready to learn | “I know what I believe in and what I think is valid, others may think differently and I’m prepared to reconsider my views” |

adapted from Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning

Some researchers argue that a qualitative shift in cognitive development takes place for some emerging adults during their mid to late twenties. As evidence, they point to studies documenting continued integration and focalization of brain functioning, and studies suggesting that this developmental period often represents a turning point, when young adults engaging in risky behaviors (e.g., gang involvement, substance abuse) or an unfocused lifestyle (e.g., drifting from job to job or relationship to relationship) seem to "wake up" and take ownership for their own development. It is a common point for young adults to make decisions about completing or returning to school, and making and following through on decisions about vocation, relationships, living arrangements, and lifestyle. Many young adults can actually remember these turning points as a moment when they could suddenly "see" where they were headed (i.e., the likely outcomes of their risky behaviors or apathy) and actively decided to take a more self-determined pathway.

Watch It

Please watch this brief lecture by Dr. Eric Landrum to better understand the way that thinking can shift during college, according to Perry’s scheme. Notice the overall shifts in beliefs over time. Do you recognize your own thinking or the thinking of others you know in this clip?

You can view the transcript for “Perry’s Scheme of Intellectual Development” here (opens in new window).

Cognition in Middle Adulthood

The brain at midlife has been shown to not only maintain many of the abilities of young adults, but also gain new ones. Some individuals in middle age actually have improved cognitive functioning (Phillips, 2011). The brain continues to demonstrate plasticity and rewires itself in middle age based on experiences. Research has demonstrated that older adults use more of their brains than younger adults. In fact, older adults who perform the best on tasks are more likely to demonstrate bilateralization than those who perform worst. Additionally, the amount of white matter in the brain, which is responsible for forming connections among neurons, increases into the 50s before it declines.

Emotionally, the middle-aged brain is calmer, less neurotic, more capable of managing emotions, and better able to negotiate social situations (Phillips, 2011). Older adults tend to focus more on positive information and less on negative information than do younger adults. In fact, they also remember positive images better than those younger. Additionally, the older adult’s amygdala responds less to negative stimuli. Lastly, adults in middle adulthood make better financial decisions, a capacity which seems to peak at age 53, and show better economic understanding. Although greater cognitive variability occurs among middle aged adults when compared to those both younger and older, those in midlife who experience cognitive improvements tend to be more physically, cognitively, and socially active.

Crystalized versus Fluid Intelligence

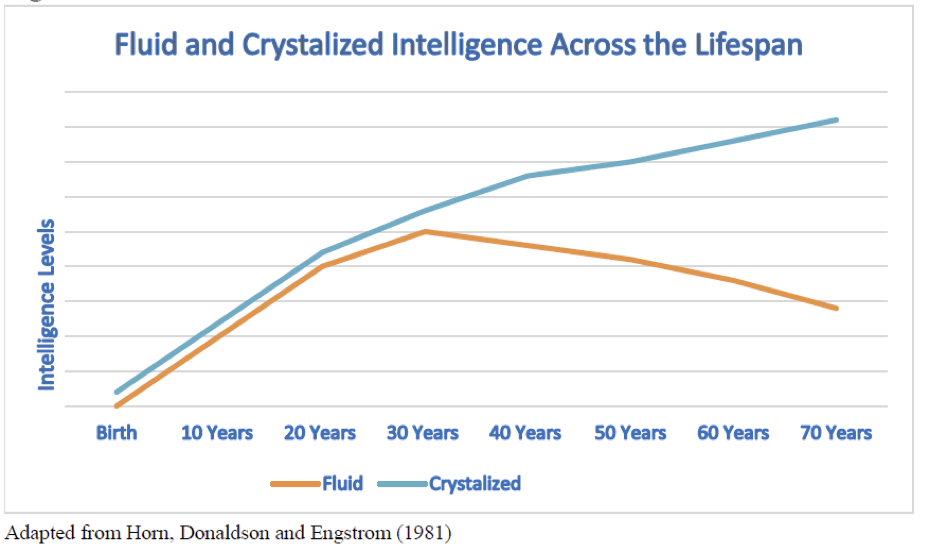

Intelligence is influenced by heredity, culture, social contexts, personal choices, and certainly age. One distinction in specific intelligences noted in adulthood, is between fluid intelligence, which refers to the capacity to learn new ways of solving problems and performing activities quickly and abstractly, and crystallized intelligence, which refers to the accumulated knowledge of the world we have acquired throughout our lives (Salthouse, 2004). These intelligences are distinct, and show different developmental pathways as pictured in Figure 10.22. Fluid intelligence tends to decrease with age (staring in the late 20s to early 30s), whereas crystallized intelligence generally increases all across adulthood (Horn et al., 1981; Salthouse, 2004).

Fluid intelligence, sometimes called the mechanics of intelligence, tends to rely on perceptual speed of processing, and perceptual speed is one of the primary capacities that shows age-graded declines starting in early adulthood, as seen not only in cognitive tasks but also in athletic performance and other tasks that require speed. In contrast, research demonstrates that crystallized intelligence, also called the pragmatics of intelligence, continues to grow all during adulthood, as older adults acquire additional semantic knowledge, vocabulary, and language. As a result, adults generally outperform younger people on tasks where this information is useful, such as measures of history, geography, and even on crossword puzzles (Salthouse, 2004). It is this superior knowledge, combined with a slower and more complete processing style, along with a more sophisticated understanding of the workings of the world around them, that gives older adults the advantage of “wisdom” over the advantages of fluid intelligence which favor the young (Baltes et al., 1999; Scheibe et al., 2009).

These differential changes in crystallized versus fluid intelligence help explain why older adults do not necessarily show poorer performance on tasks that also require experience (i.e., crystallized intelligence), although they show poorer memory overall. A young chess player may think more quickly, for instance, but a more experienced chess player has more knowledge to draw upon.

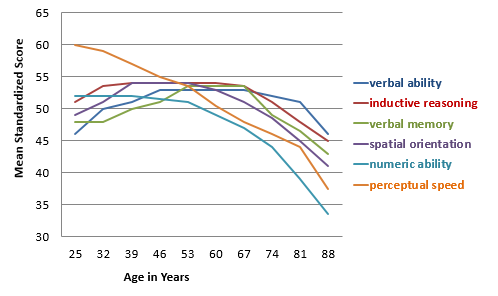

Seattle Longitudinal Study

The Seattle Longitudinal Study has tracked the cognitive abilities of adults since 1956. Every seven years the current participants are evaluated, and new individuals are also added. Approximately 6000 people have participated thus far, and 26 people from the original group are still in the study today. Current results demonstrate that middle-aged adults perform better on four out of six cognitive tasks than those same individuals did when they were young adults. Verbal memory, spatial skills, inductive reasoning (generalizing from particular examples), and vocabulary increase with age until one’s 70s (Schaie, 2005; Willis & Shaie, 1999). In contrast, perceptual speed declines starting in early adulthood, and numerical computation shows declines starting in middle and late adulthood (see Figure 10.23).

Cognitive skills in the aging brain have been studied extensively in pilots, and similar to the Seattle Longitudinal Study results, older pilots show declines in processing speed and memory capacity, but their overall performance seems to remain intact. According to Phillips (2011) researchers tested pilots age 40 to 69 as they performed on flight simulators. Older pilots took longer to learn to use the simulators but subsequently performed better than younger pilots at avoiding collisions.

Tacit knowledge is knowledge that is pragmatic or practical and learned through experience rather than explicitly taught, and it also increases with age (Hedlund et al., 2002). Tacit knowledge might be thought of as "know-how" or "professional instinct." It is referred to as tacit because it cannot be codified or written down. It does not involve academic knowledge, rather it involves being able to use skills and to problem-solve in practical ways. Tacit knowledge can be seen clearly in the workplace and underlies the steady improvements in job performance documented across age and experience, as seen for example, in the performance of both white and blue collar workers, such as carpenters, chefs, and hair dressers.

Try It

Cognition in Late Adulthood

Attention

Changes in sensory functioning and speed of processing information in late adulthood often translate into changes in attention (Jefferies et al., 2015). Research has shown that older adults are less able to selectively focus on information while ignoring distractors (Jefferies et al., 2015; Wascher et al., 2012), although Jefferies and her colleagues found that when given double time, older adults could perform at the same level as young adults. Other studies have also found that older adults have greater difficulty shifting their attention between objects or locations (Tales et al., 2002).

Consider the implication of these attentional changes for older adults. How does maintenance or loss of cognitive ability affect older adults’ everyday lives? Researchers have studied cognition in the context of several different everyday activities. One example is driving. Although older adults often have more years of driving experience, cognitive declines related to reaction time or attentional processes may pose limitations under certain circumstances (Park & Gutchess, 2000). In contrast, research on interpersonal problem solving suggests that older adults use more effective strategies than younger adults to navigate through social and emotional problems (Blanchard-Fields, 2007). In the context of work, researchers rarely find that older individuals perform more poorly on the job (Park & Gutchess, 2000). Similar to everyday problem solving, older workers may develop more efficient strategies and rely on expertise to compensate for cognitive declines.

Problem Solving

Declines with age are found on problem-solving tasks that require processing non-meaningful information quickly-- a kind of task that might be part of a laboratory experiment on mental processes. However, many real-life challenges facing older adults do not rely on speed of processing or making choices on one’s own. Older adults resolve everyday problems by relying on input from others, such as family and friends. They are also less likely than younger adults to delay making decisions on important matters, such as medical care (Strough et al., 2003; Meegan & Berg, 2002).

What might explain these deficits as we age?

The processing speed theory, proposed by Salthouse (1996, 2004), suggests that as the nervous system slows with advanced age our ability to process information declines. This slowing of processing speed may explain age differences on a variety of cognitive tasks. For instance, as we age, working memory becomes less efficient (Craik & Bialystok, 2006). Older adults also need longer time to complete mental tasks or make decisions. Yet, when given sufficient time (to compensate for declines in speed), older adults perform as competently as do young adults (Salthouse, 1996). Thus, when speed is not imperative to the task, healthy older adults generally do not show cognitive declines.

In contrast, inhibition theory argues that older adults have difficulty with tasks that require inhibitory functioning, or the ability to focus on certain information while suppressing attention to less pertinent information (Hasher & Zacks, 1988). Evidence comes from directed forgetting research. In directed forgetting people are asked to forget or ignore some information, but not other information. For example, you might be asked to memorize a list of words but are then told that the researcher made a mistake and gave you the wrong list and asks you to “forget” this list. You are then given a second list to memorize. While most people do well at forgetting the first list, older adults are more likely to recall more words from the “directed-to-forget” list than are younger adults (Andrés et al., 2004).

Aging stereotypes exaggerate cognitive losses

While there are information processing losses in late adulthood, many argue that research exaggerates normative losses in cognitive functioning during old age (Garrett, 2015). One explanation is that the type of tasks that people are tested on tend to be meaningless. For example, older individuals are not motivated to remember a random list of words in a study, but they are motivated for more meaningful material related to their life, and consequently perform better on those tests. Another reason is that researchers often estimate age declines from age differences found in cross-sectional studies. However, when age comparisons are conducted longitudinally (thus removing cohort differences from age comparisons), the extent of loss is much smaller (Schaie, 1994).

A third possibility is that losses may be due to the disuse of various skills. When older adults are given structured opportunities to practice skills, they perform as well as they had previously. Although diminished speed is especially noteworthy during late adulthood, Schaie (1994) found that when the effects of speed are statistically removed, fewer and smaller declines are found in other aspects of an individual’s cognitive performance. In fact, Salthouse and Babcock (1991) demonstrated that processing speed accounted for all but 1% of age-related differences in working memory when testing individuals from ages 18 to 82. Finally, it is well established that hearing and vision decline as we age. Longitudinal research has found that deficits in sensory functioning explain age differences in a variety of cognitive abilities (Baltes & Lindenberger, 1997). Not surprisingly, more years of education, higher income, and better health care (which go together) are associated with higher levels of cognitive performance and slower cognitive decline (Zahodne et al., 2015).

Watch It

Watch this video from SciShow Psych to learn about ways to keep the mind young and active.

You can view the transcript for “The Best Ways to Keep Your Mind Young” here (opens in new window).

Intelligence and Wisdom

When looking at scores on traditional intelligence tests, tasks measuring verbal skills show minimal or no age-related declines, while scores on performance tests, which measure solving problems quickly, decline with age (Botwinick, 1984). This profile mirrors crystalized and fluid intelligence. Baltes (1993) introduced two additional types of intelligence to reflect cognitive changes in aging. Pragmatics of intelligence are cultural exposure to facts and procedures that are maintained as one ages and are similar to crystalized intelligence. Mechanics of intelligence are dependent on brain functioning and decline with age, similar to fluid intelligence. Baltes indicated that pragmatics of intelligence show little decline and typically increase with age whereas mechanics decline steadily, staring at a relatively young age. Additionally, pragmatics of intelligence may compensate for the declines that occur with mechanics of intelligence. In summary, global cognitive declines are not typical as one ages, and individuals typically compensate for some cognitive declines, especially processing speed.

Wisdom has been defined as "expert knowledge in the fundamental pragmatics of life that permits exceptional insight, judgment and advice about complex and uncertain matters" (Baltes & Smith, 1990). A wise person is insightful and has knowledge that can be used to overcome obstacles in living. Does aging bring wisdom? While living longer brings experience, it does not always bring wisdom. Paul Baltes and his colleagues (Baltes & Kunzmann, 2004; Baltes & Staudinger, 2000) suggest that wisdom is rare. In addition, the emergence of wisdom can be seen in late adolescence and young adulthood, with there being few gains in wisdom over the course of adulthood (Staudinger & Gluck, 2011). This would suggest that factors other than age are stronger determinants of wisdom. Occupations and experiences that emphasize others rather than self, along with personality characteristics, such as openness to experience and generativity, are more likely to provide the building blocks of wisdom (Baltes & Kunzmann, 2004). Age combined with a certain types of experience and/or personality brings wisdom.

References (Click to expand)

Andrés, P., Van der Linden, M., & Parmentier, F. B. R. (2004). Directed forgetting in working memory: Age-related differences. Memory, 12, 248-256.

Baltes, P. B. & Lindenberger, U. (1997). Emergence of powerful connection between sensory and cognitive functions across the adult life span: A new window to the study of cognitive aging? Psychology and Aging, 12, 12–21.

Baltes, P. B., Staudinger, U. M., & Lindenberger, U. (1999). Lifespan Psychology: Theory and Application to Intellectual Functioning. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 471-507.

Blanchard-Fields, F. (2007). Everyday problem solving and emotion: An adult development perspective. Current Directions in Psychoogical Science, 16, 26–31

Craik, F. I., & Bialystok, E. (2006). Cognition through the lifespan: mechanisms of change. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10, 131–138.

Crone, E. A., & Dahl, R. E. (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature reviews neuroscience, 13(9), 636-650.

Elkind, D. (1967). Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Development, 38, 1025-1034.

Garrett, B. (2015). Brain and behavior (4th ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hasher, L. & Zacks, R. T. (1988). Working memory, comprehension, and aging: A review and a new view. In G.H. Bower (Ed.), The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, (Vol. 22, pp. 193–225). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Hedlund, J., Antonakis, J., & Sternberg, R. J. (2002). Tacit knowledge and practical intelligence: Understanding the lessons of experience. Retrieved from http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/army/ari_tacit_knowledge.pdf

Horn, J. L., Donaldson, G., & Engstrom, R. (1981). Apprehension, memory, and fluid intelligence decline in adulthood. Research on Aging, 3(1), 33-84.

Jefferies, L. N., Roggeveen, A. B., Ennis, J. T., Bennett, P. J., Sekuler, A. B., & Dilollo, V. (2015). On the time course of attentional focusing in older adults. Psychological Research, 79, 28-41.

Kuhn, D. (2013). Reasoning. In. P.D. Zelazo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology. (Vol. 1, pp. 744-764). New York NY: Oxford University Press.

Klaczynski, P. A., & Felmban, W. S. (2014). Heuristics and biases during adolescence: developmental reversals and individual differences.

Lin, P. (2016). Risky behaviors: Integrating adolescent egocentrism with the theory of planned behavior. Review of General Psychology, 20(4), 392-398.

Meegan, S. P., & Berg, C. A. (2002). Contexts, functions, forms, and processes of collaborative everyday problem solving in older adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26(1), 6-15. doi: 10.1080/01650250143000283

Park, D. C. & Gutchess, A. H. (2000). Cognitive aging and everyday life. In D.C. Park & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Cognitive Aging: A Primer (pp. 217–232). New York: Psychology Press.

Perry, W.G., Jr. (1970). Forms of ethical and intellectual development in the college years: A scheme. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Phillips, M. L. (2011). The mind at midlife. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/monitor/2011/04/mind-midlife.aspx

Salthouse, T. A. (1984). Effects of age and skill in typing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113, 345.

Salthouse, T. A. (1996). The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review, 103, 403-428.

Salthouse, T. A. (2004). What and when of cognitive aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 140–144.

Salthouse, T. A., & Babcock, R. L. (1991). Decomposing adult age differences in working memory. Developmental Psychology, 27, 763-776.

Schaie, K. W. (1994). The course of adult intellectual development. American Psychologist, 49, 304-311.

Schaie, K. W. (2005). Developmental influences on adult intelligence the Seattle longitudinal study. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scheibe, S., Kunzmann, U. & Baltes, P. B. (2009). New territories of Positive Lifespan Development: Wisdom and Life Longings. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Oxford handbook of Positive Psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Schwartz, P. D., Maynard, A. M., & Uzelac, S. M. (2008). Adolescent egocentrism: A contemporary view. Adolescence, 43, 441- 447.

Strough, J., Hicks, P. J., Swenson, L. M., Cheng, S., & Barnes, K. A. (2003). Collaborative everyday problem solving: Interpersonal relationships and problem dimensions. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 56, 43- 66.

Tales, A., Muir, J. L., Bayer, A., & Snowden, R. J. (2002). Spatial shifts in visual attention in normal aging and dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neuropsychologia, 40, 2000-2012.

Wasscher, E., Schneider, D., Hoffman, S., Beste, C., & Sänger, J. (2012). When compensation fails: Attentional deficits in healthy ageing caused by visual distraction. Neuropsychologia, 50, 3185-31-92.

Willis, S. L., & Schaie, K. W. (1999). Intellectual functioning in midlife. In S. L. Willis & J. D. Reid (Eds.), Life in the Middle: Psychological and Social Development in Middle Age (pp. 233-247). San Diego: Academic.

Zahodne, L. B., Stern, Y., & Manly, J. (2015). Differing effects of education on cognitive decline in diverse elders with low versus high educational attainment. Neuropsychology, 29(4), 649-657.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

CC Licensed Content

"Cognitive Development During Adolescence" by Lumen Learning is licensed under a CC BY: Attribution.

“Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0/modified and adapted by Ellen Skinner & Dan Grimes, Portland State University

Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License/modified and adapted by Ellen Skinner & Dan Grimes, Portland State University

"Puberty & Cognition" by Ellen Skinner, Dan Grimes & Brandy Brennan, Portland State University and are licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0

Media Attributions

- adolescent boys. Authored by: An Min. Provided by: Pxhere. Located at: https://pxhere.com/en/photo/1515959. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Smartphone. Photo by Roman Pohorecki from Pexels: https://www.pexels.com/photo/person-sitting-inside-car-with-black-android-smartphone-turned-on-230554/

- The Best Ways to Keep Your Mind Young. Provided by: SciShow Psych. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5DH9lAqNTG0. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- 512px-Happy_Old_Man © Marg is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license