4.1 Heredity and Chromosomes

Learning Objectives

- Describe genetic components of conception

- Describe genes and their importance in genetic inheritance

Gametes

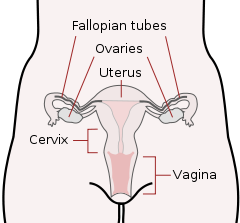

There are two types of sex cells or gametes involved in reproduction: the male gametes, or sperm, and female gametes, or ova. The male gametes are produced in the testes through a process called spermatogenesis, which begins at about 12 years of age. The female gametes, which are stored in the ovaries, are present at birth but are immature. Each ovary contains about 250,000 ova but only about 400 of these will become mature eggs (Mackon & Fauser, 2000; Rome, 1998). Beginning at puberty, one ovum ripens and is released about every 28 days, a process called oogenesis.

After the ovum or egg ripens and is released from the ovary, it is drawn into the fallopian tube and in 3 to 4 days, reaches the uterus. It is typically fertilized in the fallopian tube and continues its journey to the uterus. At ejaculation, millions of sperm are released into the vagina, but only a few reach the egg and typically, only one fertilizes the egg. Once a single sperm has entered the wall of the egg, the wall becomes hard and prevents other sperm from entering. After the sperm has entered the egg, the tail of the sperm breaks off and the head of the sperm, containing the genetic information from the father, unites with the nucleus of the egg. As a result, a new cell is formed. This cell, containing the combined genetic information from both parents, is referred to as a zygote.

Watch It

Watch as one single sperm survives the long and treacherous journey to fertilize an egg.

You can view the transcript for “Fertilization” here (opens in new window).

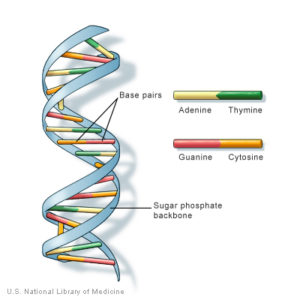

Chromosomes

While other normal human cells have 46 chromosomes (or 23 pair), gametes contain 23 chromosomes. Chromosomes are long threadlike structures found in a cell nucleus that contain genetic material known as deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). DNA is a helix-shaped molecule made up of nucleotide base pairs [adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thymine (T)]. In each chromosome, sequences of DNA make up genes that control or partially control a number of visible characteristics, known as traits, such as eye color, hair color, and so on. A single gene may have multiple possible variations or alleles. An allele is a specific version of a gene. So, a given gene may code for the trait of hair color, and the different alleles of that gene affect which hair color an individual has.

In a process called meiosis, segments of the chromosomes from each parent form pairs and genetic segments are exchanged as determined by chance. Because of the unpredictability of this exchange, the likelihood of having offspring that are genetically identical (and not twins) is one in trillions (Gould & Keeton, 1997). Genetic variation is important because it allows a species to adapt so that those who are better suited to the environment will survive and reproduce, which is an important factor in natural selection.

Genotypes and Phenotypes

When a sperm and egg fuse, their 23 chromosomes pair up and create a zygote with 23 pairs of chromosomes. Therefore, each parent contributes half the genetic information carried by the offspring; the resulting physical characteristics of the offspring (called the phenotype) are determined by the interaction of genetic material supplied by the parents (called the genotype). A person’s genotype is the genetic makeup of that individual. Phenotype, on the other hand, refers to the individual’s inherited physical characteristics.

Look in the mirror. What do you see, your genotype or your phenotype? What determines whether or not genes are expressed? Actually, this is quite complicated. Some features follow the additive pattern which means that many different genes contribute to a final outcome. Height and skin tone are examples. In other cases, a gene might either be turned on or off depending on several factors, including the gene with which it is paired or the inherited epigenetic tags.

Watch It

Watch the following clip that explains meiosis.

You can view the transcript for “MEIOSIS – MADE SUPER EASY – ANIMATION” here (opens in new window).

Link to Learning: DNA, Genes, and Inheritance

Visit the webpage “What are DNA and Genes?” from the University of Utah to better understand DNA and genes, then watch the video “What is Inheritance?” to learn how the genes from parents pass on genetic information to their children.

Determining the Sex of the Child

Twenty-two of those chromosomes from each parent are similar in length to a corresponding chromosome from the other parent. However, the remaining chromosome, the 23rd pair, looks like an X or a Y. Half of the male’s sperm contain a Y chromosome and half contain an X. All of the ova contain X chromosomes. If the child receives the combination of XY, the child will be genetically male. If it receives the XX combination, the child will be genetically female.

There are cases in which zygote does not have either an XX combination or an XY combination. A person might have XXY, XYY, XXX, XO, or 45 or 47 chromosomes as a result. Two of the more common sex-linked chromosomal disorders are Turner syndrome and Klinefelter syndrome. Turner’s syndrome occurs in 1 of every 2,500 live female births (Carroll, 2007) when an ovum which lacks a chromosome is fertilized by a sperm with an X chromosome. The resulting zygote has an XO composition. Fertilization by a Y sperm is not viable. Turner syndrome affects cognitive functioning and sexual maturation. The external genitalia appear normal, but breasts and ovaries do not develop fully and the woman does not menstruate. Turner’s syndrome also results in short stature and other physical characteristics. Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) occurs in 1 out of 700 live male births and results when an ovum containing an extra X chromosome is fertilized by a Y sperm. The Y chromosome stimulates the growth of male genitalia, but the additional X chromosome inhibits this development. An individual with Klinefelter syndrome has some breast development, infertility (this is the most common cause of infertility in males), and has low levels of testosterone.

Research has revealed that whether a person presents as a male or female is more complex than just the chromosomes received at conception. There is much more research to be done on the spectrum of sex presentation, including typical males and females in addition to people who are intersex, or have characteristics that do not necessarily fit a typical male or typical female presentation. A person’s sex assigned at birth may or may not align with their gender identity, which we will discuss in a later chapter.

Links to Learning: The Complexities of Sex Determination

This Scientific American article from 2017 has a figure that shows a variety of factors from conception to puberty that determine one’s sex.

Try It

Genetic Variation and Inheritance

Genetic variation, the genetic difference between individuals, is what contributes to a species’ adaptation to its environment. Genetic inheritance of traits for humans is based upon Gregor Mendel’s model of inheritance. For genes on an autosome (any chromosome other than a sex chromosome), the alleles and their associated traits are autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive. In this model, some genes are considered dominant because they will be expressed. Others, termed recessive, are only expressed in the absence of a dominant gene. Some characteristics which were once thought of as dominant-recessive, such as eye color, are now believed to be a result of the interaction between several genes (McKusick, 1998). Dominant traits include curly hair, facial dimples, normal vision, and dark hair. Recessive characteristics include red hair, pattern baldness, and nearsightedness.

Sickle cell anemia is an autosomal recessive disease; Huntington disease is an autosomal dominant disease. Other traits are a result of partial dominance or co-dominance in which both genes are influential. For example, if a person inherits both recessive genes for cystic fibrosis, the disease will occur. But if a person has only one recessive gene for the disease, the person would be a carrier of the disease.

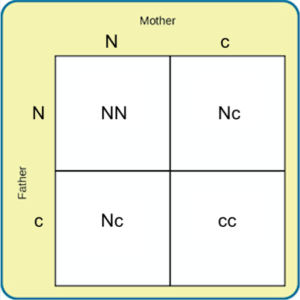

In this example, we will call the non-cystic fibrosis gene “N,” and the gene for cystic fibrosis “c.” The non-cystic fibrosis gene is dominant, which means that having the dominant allele either from one parent (Nc) or both parents (NN) will always result in the phenotype associated with the dominant allele. When someone has two copies of the same allele, they are said to be homozygous for that allele. When someone has a combination of alleles for a given gene, they are said to be heterozygous. For example, cystic fibrosis is a recessive disease which means that an individual will only have the disease if they are homozygous for that recessive allele (cc).

Imagine that a female who is a carrier of the cystic fibrosis gene has a child with a male who also is a carrier of the same disease. What are the odds that their child would inherit the disease? Both the female and the male are heterozygous for this gene (Nc). We can expect the offspring to have a 25% chance of having cystic fibrosis (cc), a 50% chance of being a carrier of the disease (Nc), and a 25% chance of receiving two non-cystic fibrosis copies of the gene (NN).

Where do harmful genes that contribute to diseases like cystic fibrosis come from? Gene mutations provide one source of harmful genes. A mutation is a sudden, permanent change in a gene. While many mutations can be harmful or lethal, once in a while a mutation benefits an individual by giving that person an advantage over those who do not have the mutation. The theory of evolution asserts that individuals best adapted to their particular environments are more likely to reproduce and pass on their genes to future generations. In order for this process to occur, there must be competition—more technically, there must be variability in genes (and resultant traits) that allow for variation in adaptability to the environment. If a population consisted of identical individuals, then any dramatic changes in the environment would affect everyone in the same way, and there would be no variation in selection. In contrast, diversity in genes and associated traits allows some individuals to perform slightly better than others when faced with environmental change. This creates a distinct advantage for individuals best suited for their environments in terms of successful reproduction and genetic transmission.

Watch It

This video demonstrates another example of the interaction of alleles using the Punnett square.

Link to Learning: Cystic Fibrosis

Visit the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation to learn more about cystic fibrosis and learn how a mutation in DNA leads to cystic fibrosis.

Try It

References (Click to expand)

Carroll, J. L. (2007). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson.

Gould, J. L. & Keeton, W. T. (1997). Biological science. New York: Norton.

Mackon, N., & Fauser, B. (2000). Aspects of ovarian follicle development throughout life. Hormone Research, 52, 161-170.

McKusick, V. A. (1998). Mendelian inheritance in man: A catalog of human genes and genetic disorders. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Rome, E. (1998). Anatomy and physiology of sexuality and reproduction. In The New Our Bodies, Ourselves (pp. 241-258). Carmichael, CA: Touchstone Books.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

- Heredity and Chromosomes. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/chapter/heredity-and-chromosomes/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology. Authored by: Laura Overstreet. Located at: http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Chromosome. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chromosome. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Human Genetics. Authored by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/waymaker-psychology/chapter/human-genetics/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Punnett Square . Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/waymaker-psychology/chapter/human-genetics/. Project: introduction to Psychology. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Gene dominance. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dominance_(genetics). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CONTENT

- An Introduction to Mendelian Genetics. Authored by: Ross Firestone. Provided by: Khan Academy. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NR3779ef9yQ&feature=youtu.be. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Fertilization. Provided by: Nucleus Medical Media. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=342&v=_5OvgQW6FG4. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- MEIOSIS – MADE SUPER EASY – ANIMATION. Authored by: Medical Institution. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=2&v=nMEyeKQClqI. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License