10.2 Piaget’s Concrete Operational and Formal Operational Stages

The Human Development Teaching & Learning Group

Learning Objectives

- Name three major advances in cognitive development that occur with the shift to concrete operational thinking.

- What do these developments allow that thinking during the preoperational stage did not?

- Provide some examples of how concrete operational thought is seen in children’s everyday functioning during middle childhood.

- What are the limitations of concrete operational thought?

- Describe Piaget’s formal operational stage and the characteristics of formal operational thought.

- Identify the advances and limitations of formal operational thought.

- Describe metacognition.

- Explore whether postformal thought exists.

Recall from the last section that during early childhood children are in Piaget’s preoperational stage, and during this stage, children are learning to think symbolically about the world. As children continue into elementary school, they develop the ability to represent ideas and events more flexibly and logically. Their rules of thinking still seem very basic by adult standards and usually operate unconsciously, but they allow children to solve problems more systematically than before, and therefore to be successful with many academic tasks.

Concrete Operational Thought

From ages 7 to 11, children are in what Piaget referred to as the concrete operational stage of cognitive development (Crain, 2005). This involves mastering the use of logic in concrete ways. The word concrete refers to that which is tangible; that which can be seen, touched, or experienced directly. Piaget called this period the concrete operational stage because children mentally “operate” on concrete objects and events. The concrete operational child is able to make use of logical principles in solving problems involving the physical world. For example, the child can understand principles of cause and effect, size, and distance. A child may unconsciously follow the rule: “If nothing is added or taken away, then the amount of something stays the same.” This simple principle helps children to understand certain arithmetic tasks, such as in adding or subtracting zero from a number, as well as to do certain classroom science experiments, such as ones involving judgments of the amounts of liquids when mixed.

The child can use logic to solve problems tied to their own direct experience, but has trouble solving hypothetical problems or considering more abstract problems. The child uses inductive reasoning, which is a logical process in which multiple premises believed to be true are combined to obtain a specific conclusion. For example, a child has one friend who is rude, another friend who is also rude, and the same is true for a third friend. The child may conclude that friends are rude. We will see that this way of thinking tends to change during adolescence as deductive reasoning emerges. We will now explore three of the major capacities that the concrete operational child exhibits.

Thought becomes multidimensional

Concrete operational children no longer focus on only one dimension of any object (such as the height of the glass) and instead can coordinate multiple dimensions simultaneously (such as the width of the glass). (That is, they are no longer limited by centration, which is why this gain is also known by the term “decentration”). Multidimensionality allows children to take multiple perspectives at the same time, to understand part-while relationships, and to cross classify objects using multiple features.

- Multiple perspectives. Recall that when young children in the preoperational stage were asked to describe the Three Mountain display from the perspective of someone sitting across the table form them, they could only report on the view form one perspective– their own. With the emergence of connote operations, children can now understand that people looking from different vantage points, see different features. They can coordinate multiple perspectives. This skill is very useful, and can be practiced, while playing with peers and settling peer disputes.

- Part-whole relationships. Think back to preoperational thought, where if you showing a long child a bouquet of six daisies and 3 roses, and asked them whether there were more daisies or flowers, they would typically answer”daisies”? They could not coordinate the two perspectives of “part” and “whole.” Now in middle childhood, these questions seem silly– of course there are more flowers, flowers include both daisies and roses. At the age, the correct answer is obvious– it’s a logical necessity.

- Classification. As children’s experiences and vocabularies grow, they build schemata and are able to organize objects in many different ways. They also understand classification hierarchies and can arrange objects into a variety of classes and subclasses.

Thought becomes operational

A second major shift in cognitive development during middle childhood coccus when thought becomes operational, by which Piaget meant that it consists of reversible, organized systems of mental actions. These systems allow children to mentally undo actions (reversibility) and to understand that certain properties of objects (like their number, mass, volume, and so on) remain constant despite transformations in appearance (conservation).

- Reversibility. The child learns that some things that have been changed can be returned to their original state. Water can be frozen and then thawed to become liquid again, but eggs cannot be unscrambled. Arithmetic operations are reversible as well: 2 + 3 = 5 and 5 – 3 = 2. Many of these cognitive skills are incorporated into the school’s curriculum through mathematical problems and in worksheets about which situations are reversible or irreversible.

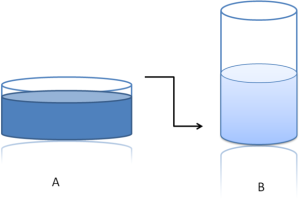

- Conservation. Remember the example in our last chapter of preoperational children thinking that a tall beaker filled with 8 ounces of water was “more” than a short, wide bowl filled with 8 ounces of water? Concrete operational children can understand the concept of conservation which means that changing one quality (in this example, height or water level) can be compensated for by changes in another quality (width). Consequently, there is the same amount of water in each container, although one is taller and narrower and the other is shorter and wider.

Thought becomes logical

A third major accomplishment of concrete operational development is that thought becomes logical, and children can reason logically about concrete events.

- Inferring higher-order characteristics. Where young children’s reasoning was focused on perceptual cues, older children can now consider a variety of specific cues and from, use the power of inference, to reach a logical conclusion about higher-order characteristics. This capacity is seen in children’s understanding of their own and other people’s capacities and personalities. For example, after a child does well on multiple multiple assignments in math, she may conclude that she is high in math ability.

- Identify defining features. Whereas young children’s understanding was dominated by the most perceptually salient features of objects, with concrete operational thought, children in middle childhood focus instead on the defining features of particular objects or states. They are not distracted by the most salient features; they recognize the underlying defining features. For example, young children might think that bicycles and toasters are alive (a kind of thought called “animism,” remember?) because they move. By middle childhood, however, children understand that even though many mechanical devices (e.g., cars, fireworks) and natural objects move (e.g., the sun, the tides), only plants and animals have a life force, which is the defining feature of being alive.

- Seriation. Arranging items along a quantitative dimension, such as length or weight, in a methodical way is now demonstrated by the concrete operational child. For example, they can methodically arrange a series of different-sized sticks in order by length. This is a complicated task that requites multidimensional thinking, because each object must be placed so that it is bigger than the one before it, but smaller than the one after it. These capacities allow children to make social comparisons as well, estimating who is bigger or better along some attribute or capacity (e.g., spelling ability, soccer skills, drawing). Social comparison plays a role in the shift in children’s estimates of their capacities; they change from the rosy overestimates of early childhood (where everyone sees themselves as “good” at everything regardless of performance) to a more accurate view that corresponds to external referents (e.g., school grades) during middle childhood.

Figure 10.16. Transitivity allows children to understand that this poodle is a dog and a mammal - Transitive inference. Being able to understand how objects are related to one another is referred to as transitivity, or transitive inference. This means that if one understands that a dog is a mammal, and that a poodle is a dog, then a poodle must be a mammal.

Limitations of concrete operational thought

These new cognitive skills increase the child’s understanding of the physical world, however according to Piaget, they still cannot think in abstract ways. Additionally, they do not think in systematic scientific ways. For example, when asked which variables influence the period that a pendulum takes to complete its arc and given weights they can attach to strings in order to do experiments, most children younger than 12 perform biased experiments from which no conclusions can be drawn (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958).

Try It

Formal Operational Thought

In the last of the Piagetian stages, the young adolescent becomes able to reason not only about tangible objects and events, but also about hypothetical or abstract ones. Hence, it has the name formal operational stage—the period when the individual can “operate” on “forms” or representations. This allows an individual to think and reason with a wider perspective. This stage of cognitive development, which Piaget called formal operational thought, marks a movement from an ability to think and reason from concrete visible events to an ability to think hypothetically and entertain what-if possibilities about the world. An individual can solve problems through abstract concepts and utilize hypothetical and deductive reasoning. Adolescents initially use trial and error to solve problems, but the ability to systematically solve a problem in a logical and methodical way emerges.

Hypothetical and Abstract Thinking

One of the major advances of formal operational thought is the capacity to think of possibility, not just reality. Adolescents’ thinking is less bound to concrete events than that of children; they can contemplate possibilities outside the realm of what currently exists. One manifestation of the adolescent’s increased facility with thinking about possibilities is the improvement of skill in deductive reasoning (also called top-down reasoning), which leads to the development of hypothetical thinking. This provides the ability to plan ahead, see the future consequences of an action and to provide alternative explanations of events. It also makes adolescents more skilled debaters, as they can reason against a friend’s or parent’s position. Adolescents also develop a more sophisticated understanding of probability.

Watch It

This video explains some of the cognitive development consistent with formal operational thought.

You can view the transcript for “Formal operational stage – Intro to Psychology” here (opens in new window).

Link to Learning: Formal Operational Thinking in the Classroom

School is a main contributor in guiding students towards formal operational thought. With students at this level, the teacher can pose hypothetical (or contrary-to-fact) problems: “What if the world had never discovered oil?” or “What if the first European explorers had settled first in California instead of on the East Coast of the United States?” To answer such questions, students must use hypothetical reasoning, meaning that they must manipulate ideas that vary in several ways at once, and do so entirely in their minds.

The hypothetical reasoning that concerned Piaget primarily involved scientific problems. His studies of formal operational thinking therefore often look like problems that middle or high school teachers pose in science classes. In one problem, for example, a young person is presented with a simple pendulum, onto which different amounts of weight can be hung (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958). The experimenter asks: “What determines how fast the pendulum swings: the length of the string holding it, the weight attached to it, or the distance that it is pulled to the side?” The young person is not allowed to solve this problem by trial-and-error with the materials themselves, but must reason a way to the solution mentally. To do so systematically, he or she must imagine varying each factor separately, while also imagining the other factors that are held constant. This kind of thinking requires facility at manipulating mental representations of the relevant objects and actions—precisely the skill that defines formal operations.

As you might suspect, students with an ability to think hypothetically have an advantage in many kinds of school work: by definition, they require relatively few “props” to solve problems. In this sense they can in principle be more self-directed than students who rely only on concrete operations—certainly a desirable quality in the opinion of most teachers. Note, though, that formal operational thinking is desirable but not sufficient for school success, and that it is far from being the only way that students achieve educational success. Formal thinking skills do not ensure that a student is motivated or well-behaved, for example, nor does it guarantee other desirable skills. The fourth stage in Piaget’s theory is really about a particular kind of formal thinking, the kind needed to solve scientific problems and devise scientific experiments. Since many people do not normally deal with such problems in the normal course of their lives, it should be no surprise that research finds that many people never achieve or use formal thinking fully or consistently, or that they use it only in selected areas with which they are very familiar (Case & Okomato, 1996). For teachers, the limitations of Piaget’s ideas suggest a need for additional theories about cognitive developments—ones that focus more directly on the social and interpersonal issues of childhood and adolescence.

Propositional thought

The appearance of more systematic, abstract thinking also allows adolescents to comprehend higher order abstract ideas, such as those inherent in puns, proverbs, metaphors, and analogies. Their increased facility permits them to appreciate the ways in which language can be used to convey multiple messages, such as satire, metaphor, and sarcasm. (Children younger than age nine often cannot comprehend sarcasm at all). This also permits the application of advanced reasoning and logical processes to social and ideological matters such as interpersonal relationships, politics, philosophy, religion, morality, friendship, faith, fairness, and honesty. This newfound ability also allows adolescents to take other’s perspectives in more complex ways, and to be able to better think through others’ points of view.

Metacognition

Meta-cognition refers to “thinking about thinking.” This often involves monitoring one’s own cognitive activity during the thinking process. Adolescents are more aware of their own thought processes and can use mnemonic devices and other strategies to think and remember information more efficiently. Metacognition provides the ability to plan ahead, consider the future consequences of an action, and provide alternative explanations of events.

Relativism

The capacity to consider multiple possibilities and perspectives often leads adolescents to the conclusion that nothing is absolute– everything appears to be relative. As a result, teens often start questioning everything that they had previously accepted– such as parent and family values, authority figures, religious practices, school rules, and political events. They may even start questioning things that took place when they were younger, like adoption or parental divorce. It is common for parents to feel that adolescents are just being argumentative, but this behavior signals a normal phase of cognitive development.

Beyond Formal Operational Thought: Post-formal Development?

According to Piagetian theory, formal operational thought emerges during adolescents. The hallmark of this type of thinking is the ability to think abstractly or to consider possibilities and ideas about circumstances not directly experienced. Thinking abstractly is only one characteristic of adult thought, however. If you compare a 15 year-old with someone in their late 30s, you would probably find that the latter considers not only what is possible, but also what is likely. Why the change? The adult has gained experience and understands that possibilities do not always become realities. They learn to base decisions on what is realistic and practical, not idealistic, and can make adaptive choices. Adults are also not as influenced by what others think.

In addition to moving toward more practical considerations, thinking in adulthood may also become more relativistic, dialectical, and systemic. These advanced ways of thinking are referred to as Postformal Thought (Sinnott, 1998). Relativistic thinking refers to the appreciation of multiple perspectives, and the understanding that knowledge depends on the perspective of the knower. In later life, adults are able to continue to entertain multiple perspectives simultaneously, and also at the same time, in the face of all those possibilities, to make a decision, commit to a specific course of action, and carry it out. This suggests that such post-formal thought goes beyond cognition to the integration of thought and action.

Abstract ideas that the adolescent believes in firmly may become standards by which the adult evaluates reality. Adolescents tend to think in dichotomies; ideas are true or false; good or bad; and there is no middle ground. However, with experience, the adult comes to recognize that there is some right and some wrong in each position, some good or some bad in a policy or approach, some truth and some falsity in a particular idea. This ability to appreciate essential paradox and to bring together salient aspects of two opposing viewpoints or positions is referred to as dialectical thought and is considered one of the most advanced aspects of postformal thinking (Basseches, 1984). Such thinking is more realistic because very few positions, ideas, situations, or people are completely right or wrong. So, for example, parents who were considered angels or devils by their adolescent children, to adult children, eventually become just people with strengths and weaknesses, endearing qualities, and faults.

Does everyone reach postformal or even formal operational thought?

Formal operational thought involves being able to think abstractly; however, this ability does not apply to all situations or all adults. Formal operational thought is influenced by experience and education. Some adults lead lives in which they are not challenged to think abstractly about their world. Many adults do not receive any formal education and are not taught to think abstractly about situations they have never experienced. Further, many people are not exposed to conceptual tools used to formally analyze hypothetical situations. Those who do think abstractly may be able to do so more easily in some subjects than others. For example, psychology majors may be able to think abstractly about psychology but be unable to use abstract reasoning in physics or chemistry. Abstract reasoning in a particular field requires a knowledge base that no one has in all areas. Consequently, our ability to think abstractly also depends on our experiences.

Try It

References (Click to expand)

Basseches, M. (1984). Dialectical thinking and adult development. Ablex Pub.

Crain, W. (2005). Theories of development concepts and applications (5th ed.). Pearson

Inhelder, B., & Piaget, J. (1958). The growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence. Basic Books.

Sinnott, J. D. (1998). The development of logic in adulthood. Plenum Press.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

- “Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0

- “Educational Psychology” by Kevin Seifert, OpenStax CNX, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 license / One sentence rephrased /Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/ce6c5eb6-84d3-4265-9554-84059b75221e@2.1.

- “Understanding the Whole Child: Prenatal Development Through Adolescence” by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Rymond, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

- Cognitive Development in Childhood by Boundless is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

- “Cognitvie Development During Middle Childhood” by Lumen Learning is Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- “Puberty & Cognition” by Ellen Skinner, Dan Grimes, & Brandy Brennan, Portland State University is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0

- Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License/modified and adapted by Ellen Skinner & Dan Grimes, Portland State University

Media Attributions

- Iraqi girl with computer. Authored by: Education in Iraq. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/olpc/2933585330/in/gallery-101408425@N06-72157644977579723/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 640px-Conservation2 © Waterlily16 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- snowflake_puzzle_nursery_play_toys-1365697.jpg!d is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Conservation_of_Liquid © Ydolem2689 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 23746727113_8d110feafd_w © John Liu is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 556px-Seriation_task_w_shapes © MehreenH is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- ezequiel-garrido-Gj7mfnSqzvE-unsplash © Ezequiel Garrido is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- adolescent boys. Authored by: An Min. Provided by: Pxhere. Located at: https://pxhere.com/en/photo/1515959. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

All Rights Reserved Content

- Formal operational stage – Intro to Psychology. Provided by: Udacity. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hvq7tq2fx1Y. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License