18.1 Parenting

The Human Development Teaching & Learning Group

Learning Objectives

- Describe challenges, transitions, and factors associated with parenthood

- Identify Baumrind’s four parenting styles

- Describe the relationship between parents and teens during adolescence

Parenthood is undergoing changes in the United States and elsewhere in the world. Women in the United States have fewer children than they did previously, and children are less likely to be living with both parents. The average fertility rate of women in the United States was about seven children in the early 1900s and has remained relatively stable at 2.1 since the 1970s (Hamilton, Martin, & Ventura, 2011; Martinez, Daniels, & Chandra, 2012). Not only are parents having fewer children, the context of parenthood has also changed. Parenting outside of marriage has increased dramatically among most socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic groups, although college-educated women are substantially more likely to be married at the birth of a child than are mothers with less education (Dye, 2010).

People are having children at older ages, too. This is not surprising given that many of the age markers for adulthood have been delayed, including marriage, completing an education, establishing oneself at work, and gaining financial independence. In 2014, the average age for American first-time mothers was 26.3 years (CDC, 2015). The birth rate for women in their early 20s has declined in recent years, while the birth rate for women in their late 30s has risen. In 2011, 40% of births were to women ages 30 and older. For Canadian women, birth rates are even higher for women in their late 30s than in their early 20s. In 2011, 52% of births were to women ages 30 and older, and the average first-time Canadian mother was 28.5 years old (Cohn, 2013). Improved birth control methods have also enabled women to postpone motherhood. Despite the fact that young people are more often delaying childbearing, most 18- to 29-year-olds want to have children and say that being a good parent is one of the most important things in life (Wang & Taylor, 2011).

The decision to become a parent should not be taken lightly. There are positives and negatives associated with parenting that should be considered. Many parents report that having children increases their well-being (White & Dolan, 2009). Researchers have also found that parents, compared to their non-parent peers, are more positive about their lives (Nelson, Kushlev, English, Dunn, & Lyubomirsky, 2013). On the other hand, researchers have also found that parents, compared to non-parents, are more likely to be depressed, report lower levels of marital quality, and feel like their relationship with their partner is more businesslike than intimate (Walker, 2011).

Galinsky (1987) was one of the first to emphasize the development of parents themselves, how they respond to their children’s development, and how they grow as parents. Parenthood is an experience that transforms one’s identity as parents take on new roles. Children’s growth and development force parents to change their roles. They must develop new skills and abilities in response to children’s development. Galinsky identified six stages of parenthood that focus on different tasks and goals (see Table 18.1).

| Galinsky’s Stages | Age of Child | Main Tasks and Goals |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: The Image-Making Stage | Planning for a child; pregnancy | Consider what it means to be a parent and plan for changes to accommodate a child |

| Stage 2: The Nurturing Stage | Infancy | Develop an attachment relationship with child and adapt to the new baby |

| Stage 3: The Authority Stage | Toddler and preschool | Parents create rules and figure out how to effectively guide their children’s behavior |

| Stage 4: The Interpretative Stage | Middle childhood | Parents help their children interpret their experiences with the social world beyond the family |

| Stage 5: The Interdependent Stage | Adolescence | Parents renegotiate their relationship with their adolescent children to allow for shared power in decision-making. |

| Stage 6: The Departure Stage | Early Adulthood | Parents evaluate their successes and failures as parents |

1. The Image-Making Stage

As prospective parents think about and form images about their roles as parents and what parenthood will bring, and prepare for the changes an infant will bring, they enter the image-making stage. Future parents develop their ideas about what it will be like to be a parent and the type of parent they want to be. Individuals may evaluate their relationships with their own parents as a model of their roles as parents.

2. The Nurturing Stage

The second stage, the nurturing stage, occurs at the birth of the baby. A parent’s main goal during this stage is to develop an attachment relationship with their baby. Parents must adapt their romantic relationships, their relationships with their other children, and with their own parents to include the new infant. Some parents feel attached to the baby immediately, but for other parents, this occurs more gradually. Parents may have imagined their infant in specific ways, but they now have to reconcile those images with their actual baby. In incorporating their relationship with their child into their other relationships, parents often have to reshape their conceptions of themselves and their identity. Parenting responsibilities are the most demanding during infancy because infants are completely dependent on caregiving.

3. The Authority Stage

The authority stage occurs when children are 2 years old until about 4 or 5 years old. In this stage, parents make decisions about how much authority to exert over their children’s behavior. Parents must establish rules to guide their child’s behavior and development. They have to decide how strictly they should enforce rules and what to do when rules are broken.

4. The Interpretive Stage

The interpretive stage occurs when children enter school (preschool or kindergarten) to the beginning of adolescence. Parents interpret their children’s experiences as children are increasingly exposed to the world outside the family. Parents answer their children’s questions, provide explanations, and determine what behaviors and values to teach. They decide what experiences to provide their children, in terms of schooling, neighborhood, and extracurricular activities. By this time, parents have experience in the parenting role and often reflect on their strengths and weaknesses as parents, review their images of parenthood, and determine how realistic they have been. Parents have to negotiate how involved to be with their children, when to step in, and when to encourage children to make choices independently.

5. The Interdependent Stage

Parents of teenagers are in the interdependent stage. They must redefine their authority and renegotiate their relationship with their adolescent as the children increasingly make decisions independent of parental control and authority. On the other hand, parents do not permit their adolescent children to have complete autonomy over their decision-making and behavior, and thus adolescents and parents must adapt their relationship to allow for greater negotiation and discussion about rules and limits.

6. The Departure Stage

During the departure stage of parenting, parents evaluate the entire experience of parenting. They prepare for their child’s departure, redefine their identity as the parent of an adult child, and assess their parenting accomplishments and failures. This stage forms a transition to a new era in parents’ lives. This stage usually spans a long time period from when the oldest child moves away (and often returns) until the youngest child leaves. The parenting role must be redefined as a less central role in a parent’s identity.

Despite the interest in the development of parents among laypeople and helping professionals, little research has examined developmental changes in parents’ experience and behaviors over time. Thus, it is not clear whether these theoretical stages are generalizable to parents of different races, ages, and religions, nor do we have empirical data on the factors that influence individual differences in these stages. On a practical note, how-to books and websites geared toward parental development should be evaluated with caution, as not all advice provided is supported by research.

Influences on Parenting

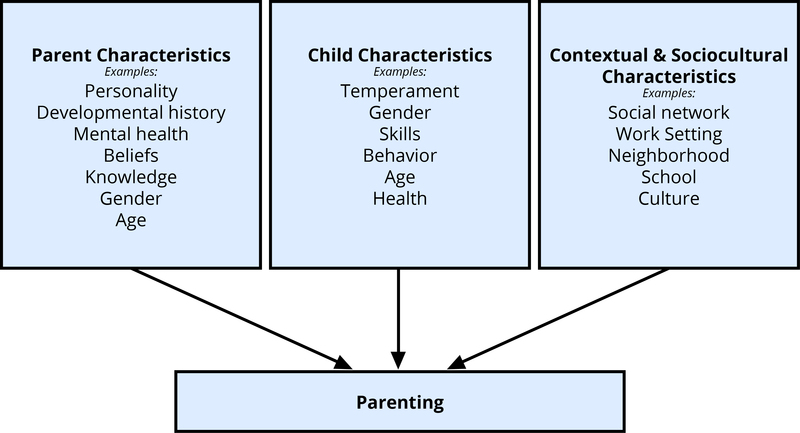

Parenting is a complex process in which parents and children influence one another. There are many reasons that parents behave the way they do. The multiple influences on parenting are still being explored. Proposed influences on parenting include: Parent characteristics, child characteristics, and contextual and sociocultural characteristics. (Belsky, 1984; Demick, 1999).

Parent Characteristics

Parents bring unique traits and qualities to the parenting relationship that affect their decisions as parents. These characteristics include the age of the parent, gender, beliefs, personality, developmental history, knowledge about parenting and child development, and mental and physical health. Parents’ personalities affect parenting behaviors. Mothers and fathers who are more agreeable, conscientious, and outgoing are warmer and provide more structure to their children. Parents who are more agreeable, less anxious, and less negative also support their children’s autonomy more than parents who are anxious and less agreeable (Prinzie, Stams, Dekovic, Reijntes, & Belsky, 2009). Parents who have these personality traits appear to be better able to respond to their children positively and provide a more consistent, structured environment for their children.

Parents’ developmental histories, or their experiences as children, also affect their parenting strategies. Parents may learn parenting practices from their own parents. Fathers whose own parents provided monitoring, consistent and age-appropriate discipline, and warmth were more likely to provide this constructive parenting to their own children (Kerr, Capaldi, Pears, & Owen, 2009). Patterns of negative parenting and ineffective discipline also appear from one generation to the next. However, parents who are dissatisfied with their own parents’ approach may be more likely to change their parenting methods with their own children.

Child Characteristics

Parenting is bidirectional. Not only do parents affect their children, children influence their parents. Child characteristics, such as gender, birth order, temperament, and health status, affect parenting behaviors and roles. For example, an infant with an easy temperament may enable parents to feel more effective, as they are easily able to soothe the child and elicit smiling and cooing. On the other hand, a cranky or fussy infant elicits fewer positive reactions from his or her parents and may result in parents feeling less effective in the parenting role (Eisenberg et al., 2008). Over time, parents of more difficult children may become more punitive and less patient with their children (Clark, Kochanska, & Ready, 2000; Eisenberg et al., 1999; Kiff, Lengua, & Zalewski, 2011). Parents who have a fussy, difficult child are less satisfied with their marriages and have greater challenges in balancing work and family roles (Hyde, Else-Quest, & Goldsmith, 2004). Thus, child temperament is one of the child characteristics that influences how parents behave with their children.

Another child characteristic is the gender of the child. Parents respond differently to boys and girls. Parents talk differently with their sons and daughters, providing more scientific explanations to their sons and using more emotion words with their daughters (Crowley, Callanan, Tenenbaum, & Allen, 2001). Parents also often assign different household chores to their sons and daughters. Girls are more often responsible for caring for younger siblings and household chores, whereas boys are more likely to be asked to perform chores outside the home, such as mowing the lawn (Grusec, goodnow, & Cohen, 1996).

Contextual Factors and Sociocultural Characteristics

The parent–child relationship does not occur in isolation; parenting is influenced by higher-order sociocultural contexts. Sociocultural characteristics, including economic hardship, religion, politics, neighborhoods, schools, and social support, also influence parenting. Parents who experience economic hardship are more easily frustrated, depressed, and sad, and these emotional characteristics affect their parenting skills (Conger & Conger, 2002).

Culture also influences parenting behaviors in fundamental ways. Although promoting the development of skills necessary to function effectively in one’s community is a universal goal of parenting, the specific skills necessary vary widely from culture to culture. Thus, parents have different goals for their children that partially depend on their culture (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2008). Parents vary in how much they emphasize goals for independence and individual achievements, maintaining harmonious relationships, and being embedded in a strong network of social relationships. Culture is also a contributing contextual factor. For example, Latina mothers who perceived their neighborhood as more dangerous showed less warmth with their children, perhaps because of the greater stress associated with living a threatening environment (Gonzales et al., 2011).

Other important contextual characteristics, such as the neighborhood, school, and social networks, also affect parenting, even though these settings do not always include both the child and the parent (Brofenbrenner, 1989). Additionally, societal hierarchies, or entrenched structures that more or less explicitly rank-order the value of different groups of people (e.g., social class, race), also impact development (Ridgeway, 2014). The objective hardships, discrimination, and prejudice some families face create an unsupportive context for the important tasks of parenting and providing for a family, which are challenging even in the best of circumstances. These contexts are complicated, and this chapter by Skinner and Raines does an excellent job of describing the higher-order contexts that shape parenting, especially for those who live in poverty or are marginalized. While I encourage you to read the entire chapter, we will summarize their major arguments here. There are three major ways that status hierarchies, like those organized around class and race that place subgroups on higher or lower rungs in a societal ladder, make parenting more difficult:

- Inequities create objective living conditions that are developmentally hazardous to children and families;

- Hardships and discrimination force people to parent under stressful conditions; and

- Families must expend effort to counteract the pervasive effects of discrimination and prejudice on the development of their children and adolescents.

Links to Learning: Required Reading

Integration of research on the effects of childhood poverty

Evans, G. (2004). The environment of childhood poverty. American Psychologist, 59, 77-92.

This short paper by Gary Evans (Evans, 2004) is a required reading for human development because it summarizes the developmentally hazardous conditions experienced by children at the bottom of the SES hierarchy. This report is especially sobering because the poorest subgroup in the US is made up of children– children under the age of 6 to be exact (National Center for Children in Poverty, 2018). It can be discouraging to read about the long list of risky conditions that poor children face, but this information is a crucial step toward deciding as a society the kinds of living conditions in which we want our children to grow up.

Although this paper was written in 2004, the conditions it describes continue to be true TODAY.

Integration of research on the effects of racism on child and adolescent health and development

This short paper, commissioned by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), is a required reading for this class because it provides an overview of research on the harmful effects of racism on child and adolescent health and development. It ends with a series of recommendations for ways in which pediatricians and the AAP can help to protect children and adolescents from these effects, and at the same time transform pediatric training and practice to work toward more just and equitable healthcare systems.

The many factors that influence parenting are depicted in the following figure.

Link to Learning

This study explores how the typical parenting styles may not capture Latinx families well and underscores the importance of incorporating cultural context in any study of parenting.

Parenting Styles

Relationships between parents and children continue to play a significant role in children’s development during early childhood. As children mature, parent-child relationships naturally change. Preschool and grade-school children are more capable, have their own preferences, and sometimes refuse or seek to compromise with parental expectations. This can lead to greater parent-child conflict, and how conflict is managed by parents further shapes the quality of parent-child relationships.

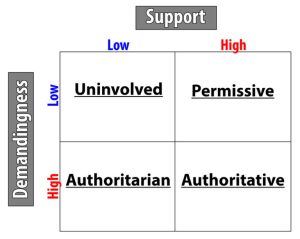

Baumrind (1971) identified a model of parenting that focuses on the level of control/ expectations that parents have regarding their children and how warm/responsive they are. This model resulted in four parenting styles. In general, children develop greater competence and self-confidence when parents have high, but reasonable expectations for children’s behavior, communicate well with them, are warm, loving and responsive, and use reasoning, rather than coercion as preferred responses to children’s misbehavior. This kind of parenting style has been described as authoritative (Baumrind, 2013). Authoritative parents are supportive and show interest in their kids’ activities but are not overbearing and allow them to make constructive mistakes. Parents allow negotiation where appropriate, and consequently this type of parenting is considered more democratic.

Authoritarian is the traditional model of parenting in which parents make the rules and children are expected to be obedient. Baumrind suggests that authoritarian parents tend to place maturity demands on their children that are unreasonably high and tend to be aloof and distant. Consequently, children reared in this way may fear rather than respect their parents and, because their parents do not allow discussion, may take out their frustrations on safer targets-perhaps as bullies toward peers.

Permissive parenting involves holding expectations of children that are below what could be reasonably expected from them. Children are allowed to make their own rules and determine their own activities. Parents are warm and communicative but provide little structure for their children. Children fail to learn self-discipline and may feel somewhat insecure because they do not know the limits.

Uninvolved (sometimes called neglectful) parents are disengaged from their children. They do not make demands on their children and are non-responsive. These children can suffer in school and in their relationships with their peers (Gecas & Self, 1991).

Keep in mind that most parents do not follow any model completely. Real people tend to fall somewhere in between these styles. Sometimes parenting styles change from one child to the next or in times when the parent has more or less time and energy for parenting. Parenting styles can also be affected by concerns the parent has in other areas of his or her life. For example, parenting styles tend to become more authoritarian when parents are tired and perhaps more authoritative when they are more energetic. Sometimes parents seem to change their parenting approach when others are around, maybe because they become more self-conscious as parents or are concerned with giving others the impression that they are a “tough” parent or an “easy-going” parent. Additionally, parenting styles may reflect the type of parenting someone saw modeled while growing up.

Culture

The impact of culture and class cannot be ignored when examining parenting styles. The model of parenting described above assumes that the authoritative style is the best because this style is designed to help the parent raise a child who is independent, self-reliant and responsible. These are qualities favored in “individualistic” cultures such as the United States, particularly by the middle class. However, in “collectivistic” cultures such as China or Korea, being obedient and compliant are favored behaviors. Authoritarian parenting has been used historically and reflects cultural need for children to do as they are told. African-American, Hispanic, and Asian parents tend to be more authoritarian than non-Hispanic whites. In societies where family members’ cooperation is necessary for survival, rearing children who are independent and who strive to be on their own makes no sense. However, in an economy based on being mobile in order to find jobs and where one’s earnings are based on education, raising a child to be independent is very important.

In a classic study on social class and parenting styles, Kohn (1977) explains that parents tend to emphasize qualities that are needed for their own survival when parenting their children. Working class parents are rewarded for being obedient, reliable, and honest in their jobs. They are not paid to be independent or to question the management; rather, they move up and are considered good employees if they show up on time, do their work as they are told, and can be counted on by their employers. Consequently, these parents reward honesty and obedience in their children. Middle class parents who work as professionals are rewarded for taking initiative, being self-directed, and assertive in their jobs. They are required to get the job done without being told exactly what to do. They are asked to be innovative and to work independently. These parents encourage their children to have those qualities as well by rewarding independence and self-reliance. Parenting styles can reflect many elements of culture.

Parents and Teens: Autonomy and Attachment

It appears that most teens do not experience adolescent “storm and stress” to the degree once famously suggested by G. Stanley Hall, a pioneer in the study of adolescent development. Only small numbers of teens have major conflicts with their parents (Steinberg & Morris, 2001), and most disagreements are minor. For example, in a study of over 1,800 parents of adolescents from various cultural and ethnic groups, Barber (1994) found that conflicts occurred over day-to-day issues such as homework, money, curfews, clothing, chores, and friends. These disputes typically occur because an adolescent’s desire for independence and autonomy conflicts with parental supervision and control. These types of arguments tend to decrease as teens develop (Galambos & Almeida, 1992).

Teens report more conflict with their mothers (than their fathers), as many mothers believe they should still have some control over many of these areas, but at the same time teens often report that their mothers are also more encouraging and supportive (Costigan, Cauce, & Etchison, 2007). As teens grow older, more compromise is reached between parents and teenagers (Smetana, 2011). Teenagers begin to behave more responsibly and parents increasingly recognize their need for autonomy. Parents are more controlling of daughters, especially early maturing girls, than they are sons (Caspi, Lynam, Moffitt, & Silva, 1993). In addition, culture and ethnicity also play a role in how restrictive parents are with the daily lives of their children (Chen, Vansteenkiste, Beyers, Soensens, & Van Petegem, 2013).

Teenagers benefit from supportive, less conflict-ridden relationships with parents. Research on attachment in adolescence find that teens who are still securely attached to their parents have fewer emotional problems (Rawatlal, Kliewer & Pillay, 2015), are less likely to engage in drug abuse and other criminal behaviors (Meeus, Branje & Overbeek, 2004), and have more positive peer relationships (Shomaker & Furman, 2009).

Try It

Watch It

This episode of VICE takes a journey to Sweden and follows a gender non-conforming family to find out what it’s like to grow up without the gender binary.

References (Click to expand)

Abuhatoum, S., & Howe, N. (2013). Power in sibling conflict during early and middle childhood. Social Development, 22, 738-754.

Barber, B. K., Olsen, J. E., & Shagle, S. C. (1994). Associations between parental psychological and behavioral control and youth internalized and externalized behaviors. Child development, 65(4), 1120-1136.

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph, 4(1), part 2.

Baumrind, D. (2013). Authoritative parenting revisited: History and current status. In R. E. Larzelere, A. Sheffield, & A. W. Harrist (Eds.). Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development (pp. 11-34). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55, 83–96.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1989). Ecological systems theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Annals of Child Development, Vol. 6 (pp. 187–251). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Caspi, A., Lynam, D., Moffitt, T. E., & Silva, P. A. (1993). Unraveling girls’ delinquency: Biological, dispositional, and contextual contributions to adolescent misbehavior. Developmental Psychology, 29(1), 19-30.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). Births and natality. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/births.htm

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Soensens, B., & Van Petegem, S. (2013). Autonomy in family decision making for Chinese adolescents: Disentangling the dual meaning of autonomy. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 1184-1209.

Clark, L. A., Kochanska, G., & Ready, R. (2000). Mothers’ personality and its interaction with child temperament as predictors of parenting behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 274–285.

Cohn, D. (2013). In Canada, most babies now born to women 30 and older. Pew Research Center.

Conger, R. D., & Conger, K. J. (2002). Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 361–373.

Costigan, C. L., Cauce, A. M., & Etchinson, K. (2007). Changes in African American mother-daughter relationships during adolescence: Conflict, autonomy, and warmth. In B. J. R. Leadbeater & N. Way (Eds.), Urban girls revisited: Building strengths (pp. 177-201). New York NY: New York University Press.

Crowley, K., Callanan, M. A., Tenenbaum, H. R., & Allen, E. (2001). Parents explain more often to boys than to girls during shared scientific thinking. Psychological Science, 12, 258–261.

Demick, J. (1999). Parental development: Problem, theory, method, and practice. In R. L. Mosher, D. J. Youngman, & J. M. Day (Eds.), Human development across the life span: Educational and psychological applications (pp. 177–199). Praeger.

Dunn, J., & Munn, P. (1987). Development of justification in disputes with mother and sibling. Developmental Psychology, 23, 791-798.

Dye, J. L. (2010). Fertility of American women: 2008. Current Population Reports. Retrieved from www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p20-563.pdf.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Guthrie, I.K., Murphy, B.C., & Reiser, M. (1999). Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Development, 70, 513-534.

Eisenberg, N., Hofer, C., Spinrad, T., Gershoff, E., Valiente, C., Losoya, S. L., Zhou, Q., Cumberland, A., Liew, J., Reiser, M., & Maxon, E. (2008). Understanding parent-adolescent conflict discussions: Concurrent and across-time prediction from youths’ dispositions and parenting. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 73, (Serial No. 290, No. 2), 1-160.

Galambos, N. L., & Almeida, D. M. (1992). Does parent-adolescent conflict increase in early adolescence?. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 737-747.

Galinsky, E. (1987). The six stages of parenthood. Perseus Books.

Gecas, V., & Seff, M. (1991). Families and adolescents. In A. Booth (Ed.), Contemporary families: Looking forward, looking back. Minneapolis, MN: National Council on Family Relations.

Gershoff, E. T. (2008). Report on physical punishment in the United States: What research tell us about its effects on children. Columbus, OH: Center for Effective Discipline.

Gonzales, N. A., Coxe, S., Roosa, M. W., White, R. M. B., Knight, G. P., Zeiders, K. H., & Saenz, D. (2011). Economic hardship, neighborhood context, and parenting: Prospective effects on Mexican-American adolescent’s mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 98–113.

Grusec, J. E., Goodnow, J. J., & Cohen, L. (1996). Household work and the development of concern for others. Developmental Psychology, 32, 999–1007.

Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., & Ventura, S. J. (2011). Births: Preliminary data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports, 60(2). Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Howe, N., Rinaldi, C. M., Jennings, M., & Petrakos, H. (2002). “No! The lambs can stay out because they got cozies”: Constructive and destructive sibling conflict, pretend play, and social understanding. Child Development, 73, 1406-1473.

Hyde, J. S., Else-Quest, N. M., & Goldsmith, H. H. (2004). Children’s temperament and behavior problems predict their employed mothers’ work functioning. Child Development, 75, 580–594.

Kerr, D. C. R., Capaldi, D. M., Pears, K. C., & Owen, L. D. (2009). A prospective three generational study of fathers’ constructive parenting: Influences from family of origin, adolescent adjustment, and offspring temperament. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1257–1275.

Kiff, C. J., Lengua, L. J., & Zalewski, M. (2011). Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 251–301.

Kohn, M. L. (1977). Class and conformity. (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kramer, L., & Gottman, J. M. (1992). Becoming a sibling: “With a little help from my friends.” Developmental Psychology, 28, 685-699.

MacKenzie, M. J., Nicklas, E., Waldfogel, J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2013). Spanking and child development across the first decade of life. Pediatrics, 132(5), e1118-e1125.

Martinez, G., Daniels, K., & Chandra, A. (2012). Fertility of men and women aged 15-44 years in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth, 2006-2010. National Health Statistics Reports, 51(April). Hyattsville, MD: U.S., Department of Health and Human Services.

Meeus, W., Branje, S., & Overbeek, G. J. (2004). Parents and partners in crime: A six-year longitudinal study on changes in supportive relationships and delinquency in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 45(7), 1288-1298.

Prinzie, P., Stams, G. J., Dekovic, M., Reijntjes, A. H., & Belsky, J. (2009). The relations between parents’ Big Five personality factors and parenting: A meta-review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 351–362.

Ram, A., & Ross, H. (2008). “We got to figure it out”: Information-sharing and siblings’ negotiations of conflicts of interest. Social Development, 17, 512-527.

Rawatlal, N., Kliewer, W., & Pillay, B. J. (2015). Adolescent attachment, family functioning and depressive symptoms. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 21(3), 80-85. doi:10.7196/SAJP.8252

Save the Children. (2019). Child protection. Retrived from https://www.savethechildren.net/what-we-do/child-protection

Shomaker, L. B., & Furman, W. (2009). Parent-adolescent relationship qualities, internal working models, and attachment styles as predictors of adolescents’ interactions with friends. Journal or Social and Personal Relationships, 2, 579-603.

Smetana, J. G. (2011). Adolescents, families, and social development. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Smith, B. L. (2012). The case against spanking. Monitor on Psychology, 43(4), 60.

Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. S. (2001). Adolescent development. Annual review of psychology, 52(1), 83-110.

Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Way, N., Hughes, D., Yoshikawa, H., Kalman, R. K., & Niwa, E. Y. (2008). Parents’ goals for children: The dynamic coexistence of individualism and collectivism in cultures and individuals. Social Development, 17, 183–209.

United Nations. (2014). Committee on the rights of the child. Retrieved from http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CRC/Shared%20Documents/VAT/CRC_C_VAT_CO_2_16302_E.pdf

Wang, W., & Taylor, P. (2011). For Millennials, parenthood trumps marriage. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Licenses & Attributions (Click to expand)

OER Attribution:

“Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0/modified and adapted by Dan Grimes & Ellen Skinner, Portland State University

Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License/modified and adapted by Dan Grimes & Ellen Skinner, Portland State University

Additional written materials by Dan Grimes & Brandy Brennan, Portland State University and are licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0

Video Attribution:

Raised without gender by VICE is licensed All Rights Reserved and is embedded here according to YouTube terms of service.

Media Attribution:

- State Farm, https://goo.gl/Npw2fb, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/BRvSA7

- eye-for-ebony-zQQ6Y5_RtHE-unsplash-2 © Eye for Ebony is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- influences parenting © Marissa L. Diener is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- kelly-sikkema-FqqaJI9OxMI-unsplash-2 © Kelly Sikkema is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Parenting styles from Lumen Learning.